- Tammany Hall

-

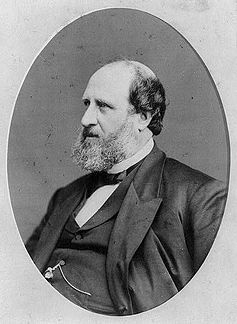

William M. Tweed, known as "Boss" Tweed, ran an efficient and corrupt political machine based on patronage and graft.

William M. Tweed, known as "Boss" Tweed, ran an efficient and corrupt political machine based on patronage and graft.

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It was the Democratic Party political machine that played a major role in controlling New York City politics and helping immigrants, most notably the Irish, rise up in American politics from the 1790s to the 1960s. It controlled Democratic Party nominations and patronage in Manhattan from the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854 through the election of John P. O'Brien in 1932. Tammany Hall was permanently weakened by the election of Fiorello La Guardia on a "fusion" ticket of Republicans, reform-minded Democrats, and independents in 1934, and, despite a brief resurgence in the 1950s, it ceased to exist in the 1960s.

The Tammany Society was named for Tamanend, a Native American leader of the Lenape, and emerged as the center for Democratic-Republican Party politics in the City in the early 19th Century. The "Hall" serving as the Society's headquarters was built in 1830 on East 14th Street, marking an era when Tammany Hall became the city affiliate of the Democratic Party, controlling most of the New York City elections afterwards.

The Society expanded its political control even further by earning the loyalty of the city's ever-expanding immigrant community, which functioned as a base of political capital. The Tammany Hall ward boss or ward heeler – "wards" were the city's smallest political units from 1686 to 1938 – served as the local vote gatherer and provider of patronage. Beginning in late 1845, Tammany power surged with the influx of millions of Irish immigrants to New York. From 1872, Tammany had an Irish "boss," and in 1928 a Tammany hero, New York Governor Al Smith won the Democratic presidential nomination. However, Tammany Hall also served as an engine for graft and political corruption, perhaps most infamously under William M. "Boss" Tweed in the mid-19th century.

Tammany Hall's influence waned in the 20th Century; in 1932, Mayor Jimmy Walker was forced from office, and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stripped Tammany of Federal patronage. Republican Fiorello La Guardia was elected Mayor on a Fusion ticket and became the first anti-Tammany Mayor to be re-elected. A brief resurgence in Tammany power in the 1950s was met with Democratic Party opposition led by Eleanor Roosevelt, Herbert Lehman, and the New York Committee for Democratic Voters. By the mid-1960s Tammany Hall ceased to exist.

Contents

History

1789–1850

The Tammany Society, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was founded in New York on May 12, 1789, originally as a branch of a wider network of Tammany Societies, the first having been formed in Philadelphia in 1772.[1] The society was originally developed as a club for "pure Americans".[2] The name "Tammany" comes from Tamanend, a Native American leader of the Lenape. The society adopted many Native American words and also their customs, going so far as to call its hall a wigwam. The first Grand Sachem, as the leader was titled, was William Mooney, an upholsterer of Nassau Street.[3]

By 1798, the Society's activities had grown increasingly politicized. High ranking Democrat-Republican Aaron Burr saw Tammany Hall as an opportunity to counter Alexander Hamilton's Society of the Cincinnati and developed it into a political machine.[2] Eventually the Tammany political machine (distinct from the Society), led by Aaron Burr, who was never a member of the Society,[3] emerged as the center for Democratic-Republican Party politics in the city. Burr used the Tammany Society for the election of 1800, in which he was elected Vice President. Without Tammany, historians believe, President John Adams might have won New York state's electoral votes and won reelection.[4]

An example of early corruption that developed from Tammany Hall came through the hall's feud with Dewitt Clinton. In 1802, Tammany Hall began a feud with Clinton after he accused Aaron Burr of being a traitor to the Democratic-Republican Party.[5] In 1803, Clinton left the United States Senate and became Mayor of New York City.[6] As mayor, Clinton enforced a spoils system and appointed his family and partisans to positions in the city's local government.[6] Tammany Hall soon realized their influence among the local political scene was no match for that of Clinton's.[6] Burr's support among New York City's residents also greatly faded after he shot and killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel.[7] Despite this, Burr maintained support from Tammany Hall's Sachems.[7] However, pressure from the public soon persuaded Tammany Hall to no longer affiliate themselves with Burr.[7]

In December of 1805, a break for Tammany Hall came when Dewitt Clinton reached out to supporters of Burr in order to gain enough support to resist the influence of the powerful Livingstone family.[7] The Livingstone family, lead by former New York City mayor Edward Livingston, was backed New York Governor Morgan Lewis and presented a significant challenge to Clinton.[8] The Tammany Hall Sachems agreed to meet with Dewitt Clinton on February 20, 1806.[8] The Burrites now thought they were assured to get their political chief reinstated.[8] However, the Tammany Hall Sachems turned on the Burrites and agreed to instead work to bring them into Clinton's fold rather than have them work together with Clintonites as a joint-union.[7] The Sachems were expelled and Tammany Hall continued to despise Clinton.[7]

Tammany Hall afterwards became a locally organized machine dedicated to stopping Clinton and Federalists from rising to power in New York.[9] In 1806, however, local Democrat-Republicans began to turn against Tammany Hall.[10] In 1808, in order to try and counter their fading influence,[11] the Sachems of Tammany Hall displayed patriotism by placing the bones of 11,500 American Revolution veterans who died on board British prison ships in a special crypt.[11] This action only gave the organization a total of $1,000.00 in donations by the local state legislators.[12] In 1809, the local Common Council cracked down on Tammany Hall and found that a number of its Sachems secretly received a huge amount of funds.[13] Following the disclosures, the Federalists won control of the state legislation and the Democratic-Republican Party barely maintained control of the local government in New York City.[14] The Tammany Hall Sachems then agreed to discipline the organization by having laws passed that established an organization that oversaw Tammany Hall's finances and limiting contributions to the organization.[15]

However, between the years 1809 and 1815, Tammany Hall slowly revived itself by accepting immigrants and by secretly building a new wigwam to hold meetings whenever new Sachems were named.[16] The Democratic-Republican Committee, a new committee which consisted of the most influential local Democratic Republicans- would now name the new Sachems as well.[17] Support for Tammany Hall also regrew after they supported the War of 1812.[18]

After 1829, Tammany Hall became the city affiliate of the Democratic Party, controlling most of the New York City elections afterwards. In the 1830s the Loco-Focos, an anti-monopoly and pro-labor faction of the Democratic Party, became Tammany's main opposition by appealing to workingmen. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s the Society expanded its political control even further by earning the loyalty of the city's ever-expanding immigrant community, which functioned as a base of political capital. The Tammany Hall "ward boss" served as the local vote gatherer and provider of patronage. New York City used the designation "ward" for its smallest political units from 1686–1938.

Immigrant support

Tammany Hall’s electoral base lay predominantly with New York’s burgeoning immigrant constituency, which often exchanged political support for Tammany Hall’s patronage. In pre-New Deal America the extralegal services that Tammany and other urban political machines provided, often served as a rudimentary public welfare system. The patronage Tammany Hall provided to immigrants, many of whom lived in extreme poverty and received little government assistance, covered three key areas. First, Tammany provided the means of physical existence in times of emergency: food, coal, rent money or a job. Second, Tammany served as a powerful intermediary between immigrants and the unfamiliar state. In an example of their involvement in the lives of citizens, in the course of one day, Tammany figure George Washington Plunkitt assisted the victims of a house fire; secured the release of six "drunks" by speaking on their behalf to a judge; paid the rent of a poor family to prevent their eviction and gave them money for food; secured employment for four individuals; attended the funerals of two of his constituents (one Italian, the other Jewish); attended a Bar Mitzvah; and attended the wedding of a Jewish couple from his ward.[19]

Tammany Hall also served as a social integrator for immigrants by familiarizing them with American society and its political institutions and by helping them become naturalized citizens. One example was the naturalization process organized by William M. Tweed. Under Tweed's regime, "naturalization committees" were established. These "committees" were made up primarily of Tammany politicians and employees, and their duties consisted of filling out paperwork, providing witnesses, and lending immigrants money for the fees required to become citizens. Judges and other city officials were bribed and otherwise compelled to go along with the workings of these committees.[20]

Tweed regime

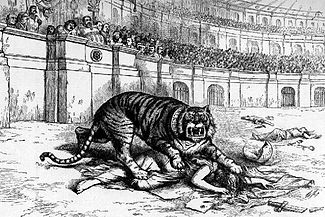

Tammany's control over the politics of New York City tightened considerably under Tweed. In 1858, Tweed utilized the efforts of Republican reformers to rein in the Democratic city government to obtain a position on the County Board of Supervisors (which he then used as a springboard to other appointments) and to have his friends placed in various offices. From this position of strength, he was elected "Grand Sachem" of Tammany, which he then used to take functional control of the city government. With his proteges elected governor of the state and mayor of the city, Tweed was able to expand the corruption and kickbacks of his "Ring" into practically every aspect of city and state governance. Although Tweed was elected to the State Senate, his true sources of power were his appointed positions to various branches of the city government. These positions gave him access to city funds and contractors, thereby controlling public works programs. This benefitted his pocketbook and those of his friends, but also provided jobs for the immigrants, especially Irish laborers, who were the electoral base of Tammany's power.[21]

Under "Boss" Tweed's dominance, the city expanded into the Upper East and Upper West Sides of Manhattan, the Brooklyn Bridge was begun, land was set aside for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, orphanages and almshouses were constructed, and social services – both directly provided by the state and indirectly funded by state appropriations to private charities – expanded to unprecedented levels. All of this activity, of course, also brought great wealth to Tweed and his friends. It also brought them into contact and alliance with the rich elite of the city, who either fell in with the graft and corruption, or else tolerated it because of Tammany's ability to control the immigrant population, of whom the "uppertens" of the city were wary.

It was therefore Tammany's demonstrated inability to control Irish laborers in the Orange riot of 1871 that began Tweed's downfall. Campaigns to topple Tweed by the New York Times and Thomas Nast of Harper's Weekly began to gain traction in the aftermath of the riot, and disgruntled insiders began to leak the details of the extent and scope of the Tweed Ring's avarice to the newspapers.

Tweed was arrested and tried in 1872. He died in Ludlow Street Jail, and political reformers took over the city and state governments.[21]

1870–1900

Tammany did not take long to rebound from Tweed's fall. Reforms demanded a general housecleaning, and former county sheriff "Honest John" Kelly was selected as the new leader. Kelly was not implicated in the Tweed scandals, and was a religious Catholic related by marriage to Archbishop John McCloskey. He cleared Tammany of Tweed's people, and tightened the Grand Sachem's control over the hierarchy. His success at revitalizing the machine was such that in the election of 1874, the Tammany candidate, William H. Wickham, unseated the unpopular reformist incumbent, William F. Havemeyer, and Democrats generally won their races, delivering control of the city back to Tammany Hall.[22]

- 1886 mayoral election

The mayoral election of 1886 was a seminal one for the organization. Union activists had founded the United Labor Party (ULP), which nominated political economist Henry George, the author of Progress and Poverty, as its standard-bearer. George was initially hesitant about running for office, but was convinced to do so after Tammany secretly offered him a seat in Congress if he would stay out of the mayoral race. Tammany had no expectation of George being elected, but knew that his candidacy and the new party were a direct threat to their own status as the putative champions of the working man.[23]

Having inadvertently provoked George into running, Tammany now needed to field a strong candidate against him, which required the cooperation of the Catholic Church in New York, which was the key to getting the support of middle-class Irish-American voters. Richard Croker, Kelly's right-hand man, has succeeded Kelly as Grand Sachem of Tammany, and he understood that he would also need to make peace with the non-Tammany "Swallowtail" faction of the Democratic Party to avoid the threat that George and the ULP posed, which was the potential re-structuring of the city's politics along class lines and away from the ethnic-based politics which has been Tammany's underpinning all along. To bring together these disparate groups, Croker nominated Abram Hewitt as the Democratic candidate for mayor. Not only was Hewitt the leader of the Swallowtails, but he was noted philanthropist Peter Cooper's son-in-law, and had an impeccable reputation. To counter both George and Hewitt, the Republican put up Theodore Roosevelt, the former city police commissioner and state assemblyman.[24]

In the end, Hewitt won the election, with George out-polling Roosevelt, whose total was some 2,000 votes less than the Republicans had normally received. Despite their second-place finish, things seemed bright for future of the labor political movement, but the ULP was not to last, and was never able to bring about a new paradigm in the city's politics. Tammany has once again succeeded and survived. More than that, Croker realized that he could utilize the techniques of the well-organized election campaign that ULP had run. Because Tammany's ward-heelers controlled the saloons, the new party had used "neighborhood meetings, streetcorner rallies, campaign clubs, Assembly District organizations, and trade legions – an entire political counterculture"[25] to run their campaign. Croker now took these innovations for Tammany's use, creating political clubhouses to take the place of the saloons and involving women and children by sponsoring family excursions and picnics. The New Tammany appeared to be more respectable, and less obviously connected to saloon-keepers and gang leaders, and the clubhouses, one in every Assembly District, were also a more efficient way of providing patronage work to those who came looking for it; one simply had to join the club, and volunteer to put in the hours needed to support it.[26]

Hewitt turned out to be a terrible mayor, due to his personality defects and his nativist views, and in 1888 Tammany ran Croker's hand-picked choice, Hugh J. Grant, who became the first New York-born Irish-American mayor. Grant allowed Croker free run of the city's contracts and offices, creating a vast patronage machine beyond anything Tweed had ever dreamed of, a status which continued under Grant's successor, Frank Gilroy. With such resources of money and manpower – the entire city workforce of 1,200 was essentially available to him when needed – Croker was able to neutralize the Swallowtails permanently. He also developed a new stream of income from the business community, which was provided with "one stop shopping": instead of bribing individual office-holders, businesses, especially the utilities, could go directly to Tammany to make their payments, which were then directed downward as necessary; such was the control Tammany had come to have over the governmental apparatus of the city.[27]

Croker mended fences with labor as well, pushing through legislation which addressed some of the inequities which had fueled the labor political movement, making Tammany once again appear to be the "Friend of the Working Man" – although he was careful always to maintain a pro-business climate of laissez-faire and low taxes. Tammany's influence was also extended once again to the state legislature, where a similar patronage system to the city's was established after Tammany took control in 1892. With the Republican boss, Thomas Platt, adopting the same methods, the two men between them essentially controlled the state.[28]

- 1894 mayoral election

In 1894, Tammany suffered a setback when, fueled by the public hearings on police corruption held by the Levox Committee based on the evidence uncovered by the Rev. Charles Parkhurst when he explored the city's demi monde undercover, a Committee of Seventy was organized by Council of Good Government Clubs to break the stranglehold that Tammany had on the city. Full of some of the city's richest men – J.P. Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Abram Hewitt and Elihu Root, among others – the committee supported William L. Strong, a millionaire dry-goods merchant, for mayor, and forced Tammany's initial candidate, merchant Nathan Straus, co-owner of Macy's and Abraham & Straus, from the election by threatening to ostracize him from New York society. Tammany then put up Hugh Grant again, despite his being publicly dirtied by the police scandals. Backed by the Committee's money, influence and their energetic campaign, and helped by Grant's apathy, Strong won the election handily, and spent the next three years running the city on the basis of "business principles", pledging an efficient government and the return of morality to city life. The election was a Republican sweep statewide: Levi Morton, a millionaire banker from Manhattan, won the governorship, and the party also ended up in control of the legislature.[29]

Still, Tammany could not be kept down for long, and in 1898 Croker, aided by the death of Henry George – which took the wind out of the sails of the potential re-invigoration of the political labor movement – shifted the Democratic Party enough to the left to pick up labor's support, and pulled back into the fold those elements outraged by the reformers' attempt to outlaw Sunday drinking and otherwise enforce their own authoritarian moral concepts on immigrant populations with different cultural outlooks. Tammany's candidate, Robert A. Van Wyck easily outpolled Seth Low, the reform candidate backed by the Citizens Union, and Tammany was back in control. Its supporters marched through the city's streets chanting, "Well, well, well, Reform has gone to Hell!"[30]

Despite occasional defeats, Tammany was consistently able to survive and prosper. Under leaders such as Charles Francis Murphy and Timothy Sullivan, it maintained control of Democratic politics in the city and the state.

In the 20th century

In 1901, anti-Tammany forces elected a reformer, Republican Seth Low, to become mayor. From 1902 until his death in 1924, Charles Francis Murphy was Tammany's boss. In 1932, the machine suffered a dual setback when Mayor James Walker was forced from office and reform-minded Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president of the United States. Roosevelt stripped Tammany of federal patronage, which had been expanded under the New Deal—and passed it instead to Ed Flynn, boss of the Bronx. Roosevelt helped Republican Fiorello La Guardia become mayor on a Fusion ticket, thus removing even more patronage from Tammany's control. La Guardia was elected in 1933 and re-elected in 1937 and 1941. He was the first anti-Tammany Mayor to be re-elected and his extended tenure weakened Tammany in a way that previous "reform" Mayors had not.

Tammany depended for its power on government contracts, jobs, patronage, corruption, and ultimately the ability of its leaders to swing the popular vote. The last element weakened after 1940 with the decline of relief programs like WPA and CCC that Tammany used to gain and hold supporters. Congressman Christopher "Christy" Sullivan was one of the last "bosses" of Tammany Hall before its collapse. Manhattan District Attorney Thomas Dewey also got longtime Tammany Hall boss Jimmy Hines convicted of bribery in 1939.[2]

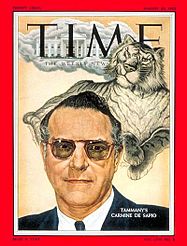

Tammany never recovered, but it staged a small scale come-back in the early 1950s under the leadership of Carmine DeSapio, who succeeded in engineering the elections of Robert Wagner, Jr. as mayor in 1953 and Averell Harriman as state governor in 1954, while simultaneously blocking his enemies, especially Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr. in the 1954 race for state Attorney General.

Eleanor Roosevelt organized a counterattack with Herbert Lehman and Thomas Finletter to form the New York Committee for Democratic Voters, a group dedicated to fighting Tammany. In 1961, the group helped remove DeSapio from power. The once mighty Tammany political machine, now deprived of its leadership, quickly faded from political importance, and by the mid-1960s it ceased to exist.

Tammany Hall's demise as the controlling group of the New York Democratic Party came about when the Village Independent Democrats under Ed Koch wrested away control of the Manhattan party.

Leaders

Tammany Hall on East 14th Street between Third Avenue and Irving Place in Manhattan, New York City (1914). The building was demolished c.1927.

Tammany Hall on East 14th Street between Third Avenue and Irving Place in Manhattan, New York City (1914). The building was demolished c.1927.

The former Tammany Hall building at 17th Street and Park Avenue South, across from Union Square, is now a theatre and a film school

The former Tammany Hall building at 17th Street and Park Avenue South, across from Union Square, is now a theatre and a film school

- 1789–1797 – William Mooney

- 1797–1804 – Aaron Burr

- 1804–1814 – Teunis Wortmann

- 1814–1817 – George Buckmaster

- 1817–1822 – Jacob Barker

- 1822–1827 – Stephen Allen

- 1827–1828 – Mordecai M. Noah

- 1828–1835 – Walter Bowne

- 1835–1842 – Isaac Varian

- 1842–1848 – Robert Morris

- 1848–1850 – Isaac Vanderbeck Fowler

- 1850–1856 – Fernando Wood

- 1857–1858 – Isaac Vanderbeck Fowler

- 1858 – Fernando Wood

- 1858–1859 – William M. Tweed & Isaac Vanderbeck Fowler

- 1859–1867 – William M. Tweed & Richard B. Connolly

- 1867–1871 – William M. Tweed

- 1872 – John Kelly & John Morrissey

- 1872–1886 – John Kelly

- 1886–1902 – Richard Croker

- 1902 – Lewis Nixon

- 1902 – Charles Francis Murphy, Daniel F. McMahon & Louis F. Haffen

- 1902–1924 – Charles Francis Murphy

- 1924–1929 – George Washington Olvany

- 1929–1934 – John F. Curry

- 1934–1937 – James J. Dooling

- 1937–1942 – Christopher D. Sullivan

- 1942 – Charles H. Hussey

- 1942–1944 – Michael J. Kennedy

- 1944–1947 – Edward V. Loughlin

- 1947–1948 – Frank J. Sampson

- 1948–1949 – Hugo E. Rogers

- 1949–1961 – Carmine DeSapio

- 1961–1964 – Edward N. Costikyan

- 1964–1968 – J. Raymond Jones

Headquarters

In its very early days, the Tammany Society used a room in a tavern on Chatham Street – which is now Park Row – as an unofficial campaign headquarters on election days, referring to it as "Tammanial Hall".[31] In 1791, the society opened a museum designed to collect together artifacts relating to the events and history of the United States. Originally presented in an upper room of City Hall, it moved to the Merchant's Exchange when that proved to be too small. The museum was unsuccessful, and the Society severed its connections with it in 1795.[32]

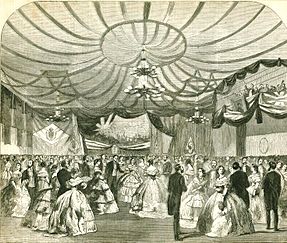

The original headquarters building for the Society, the first Tammany Hall, was built in 1830 at 141 East 14th Street between Third and Fourth Avenues, but the building was not primarily the clubhouse of a political organization:

Tammany Hall merged politics and entertainment, already stylistically similar, in its new headquarters ... The Tammany Society kept only one room for itself, renting the rest to entertainment impresarios: Don Bryant's Minstrels,a German theater company, classical concerts and opera. The basement – in the French mode – offered the Café Ausant, where one could see tableux vivant, gymnastic exhibitions, pantomimes, and Punch and Judy shows. There was also a bar, a bazaar, a Ladies' Cafe, and an oyster saloon. All this – with the exception of Bryant's – was open from seven till midnight for a combination price of fifty cents.[33]

The building had an auditorium of sufficient size to hold public meetings, and a smaller one that became Tony Pastor's Music Hall, where vaudeville had its beginnings.[34]

In 1927 the building on 14th Street was sold, to make way for the new tower being added to the Consolidated Edison Company Building. The Society's new building on East 17th Street and Union Square East was finished and occupied by 1929.[35] After the Society folded in the 1960s, the building was turned over to commercial usage, and now houses the New York Film Academy and the Union Square Theatre.

Miscellany

- A large decorated flagpole base within Union Square Park is dedicated to sachem Charles Francis Murphy.

See also

- Tammanies

References

- Notes

- ^ Hodge, Frederick Webb (ed.) Handbook of Indians North of Mexico (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 30. GPO 1911), 2:683–684

- ^ a b c "Sachems & Sinners: An Informal History of Tammany Hall" Time (August 22, 1955)

- ^ a b The History of New York State

- ^ Parmet and Hecht, pp. 149–150

- ^ Myers, p. 20

- ^ a b c Myers, p. 21

- ^ a b c d e f Myers, p. 22

- ^ a b c Myers, p. 23

- ^ Myers, p. 24

- ^ Myers, p. 25

- ^ a b Myers, p. 26

- ^ Myers, p. 27

- ^ Myers, pp. 27-30

- ^ Myers, p. 30

- ^ Myers, pp. 31-32

- ^ Myers, pp. 36-38

- ^ Myers, p. 38

- ^ Myers, p. 39

- ^ Riordin, pp.91–93

- ^ Connable and Silberfarb, p.154

- ^ a b Burrows & Wallace, p.837 and passim

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p.1027

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p.1099

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp.1103-1106

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, p.1100

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp.1106-1108

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp.1108-1109

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp.1109-1110

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp.1192-1194

- ^ Burrows & Wallace, pp.1206-1208

- ^ Burrows & Wallace p.322

- ^ Burrows & Wallace p.316

- ^ Burrows & Wallace p.995

- ^ Wurman, Richard Saul. Access New York City. New York: HarperCollins, 2000. ISBN 0-06-277274-0

- ^ "Second Tammany Hall Building Proposed as Historic Landmark". http://www.preserve2.org/gramercy/proposes/new/district/100_102e17.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195116348.

- Connable, Alfred, and Silberfarb, Edward. Tigers of Tammany: Nine Men Who Ran New York. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967.

- Myers, Gustavus. The history of Tammany Hall. Boni & Liveright, 1917

- Parmet, Herbert S. and Hecht, Marie B. Aaron Burr; Portrait of an Ambitious Man 1967.

- Riordan, William. Plunkitt of Tammany Hall: A Series of Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics New York: E.P. Dutton, 1963

- 1915 memoir of New York City ward boss George Washington Plunkitt who coined the term "honest graft"

- This article incorporates text from the Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site operated by the National Park Service, placed into the public domain.

- Further reading

- Allen, Oliver E. The Tiger: The Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall (1993)

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Tammany Hall". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Tammany Hall". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Cornwell, Jr., Elmer E. "Bosses, Machines, and Ethnic Groups", in Callow Jr., Alexander B. (ed.) The City Boss in America: An Interpretive Reader. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- Costikyan, Edward N. "Politics in New York City: a Memoir of the Post-war Years." New York History 1993 74(4): 414–434. ISSN 0146-437x

- Costikyan was a member of the Tammany Executive Committee 1955–1964, and laments the passing of its social services and its unifying force

- Erie, Steven P. Rainbow's End: Irish-Americans and the Dilemmas of Urban Machine Politics, 1840–1985 (1988).

- Finegold, Kenneth. Experts and Politicians: Reform Challenges to Machine Politics in New York, Cleveland, and Chicago (1995)

- LaCerra, Charles. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Tammany Hall of New York. University Press of America, 1997. 118 pp.

- Lash, Joseph. Eleanor, The Years Alone. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1972, 274–276.

- Lui, Adonica Y. "The Machine and Social Policies: Tammany Hall and the Politics of Public Outdoor Relief, New York City, 1874–1898." in Studies in American Political Development (1995) 9(2): 386–403. ISSN 0898-588x

- Mandelbaum, Seymour J. Boss Tweed's New York (1965) ISBN 0-471-56652-7

- Moscow, Warren. The Last of the Big-Time Bosses: The Life and Times of Carmine de Sapio and the Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall (1971)

- Mushkat, Jerome. Fernando Wood: A Political Biography (1990)

- Ostrogorski, M.. Democracy and the Party System in the United States (1910)

- Sloat, Warren. A Battle for the Soul of New York: Tammany Hall, Police Corruption, Vice, and Reverend Charles Parkhurst's Crusade against Them, 1892–1895. Cooper Square, 2002. 482 pp.

- Stave, Bruce M.; Allswang, John M.; McDonald, Terrence J. and Teaford, Jon C. "A Reassessment of the Urban Political Boss: An Exchange of Views" History Teacher, Vol. 21, No. 3 (May, 1988) , pp. 293–312

- Steffens, Lincoln. The Shame of the Cities (1904)

- Muckraking expose of political machines in major cities

- Stoddard, T.L. Master of Manhattan (1931), on Crocker

- Thomas, Samuel J. "Mugwump Cartoonists, the Papacy, and Tammany Hall in America's Gilded Age." Religion and American Culture 2004 14(2): 213–250. ISSN 1052-1151 Fulltext: in Swetswise, Ingenta and Ebsco

- Weiss, Nancy J. Charles Francis Murphy, 1858–1924: respectability and responsibility in Tammany politics (1968).

- Werner, M. R. Tammany Hall (1932)

- Zink, Harold B. City Bosses in the United States: A Study of Twenty Municipal Bosses (1930)

External links

Categories:- Political history of New York City

- Democratic Party (United States) organizations

- Political corruption in the United States

- Irish American history

- 1789 establishments in the United States

- 1961 disestablishments

- Leaders of Tammany Hall

- Algonquian loanwords

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.