- Primary ciliary dyskinesia

-

Primary ciliary dyskinesia Classification and external resources

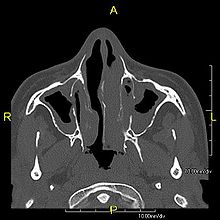

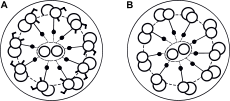

Normal cilia (A) cilia in Kartagener's syndrome (B).ICD-10 Q89.3* ICD-9 759.3* OMIM 244400 242650 DiseasesDB 7111 29887 eMedicine med/1220 ped/1166 MeSH D002925 Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), also known as immotile ciliary syndrome or Kartagener Syndrome (KS), is a rare, ciliopathic, autosomal recessive genetic disorder that causes a defect in the action of the cilia lining the respiratory tract (lower and upper, sinuses, Eustachian tube, middle ear) and fallopian tube, and also of the flagella of sperm in males.

Respiratory epithelial motile cilia, which resemble microscopic "hairs" (although structurally and biologically unrelated to hair), are complex organelles that beat synchronously in the respiratory tract, moving mucus toward the throat. Normally, cilia beat 7 to 22 times per second, and any impairment can result in poor mucociliary clearance, with subsequent upper and lower respiratory infection. Cilia also are involved in other biological processes (such as nitric oxide production), which are currently the subject of dozens of research efforts. As the functions of cilia become better understood, the understanding of PCD should be expected to advance.

Contents

Classification

When accompanied by the combination of situs inversus (reversal of the internal organs), chronic sinusitis, and bronchiectasis, it is known as Kartagener syndrome. The phrase "immotile ciliary syndrome" is no longer favored as the cilia do have movement, but may be inefficient or unsychronized.

Signs and symptoms

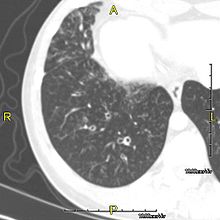

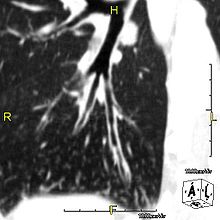

The main consequence of impaired ciliary function is reduced or absent mucus clearance from the lungs, and susceptibility to chronic recurrent respiratory infections, including sinusitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, and otitis media. Progressive damage to the respiratory system is common, including progressive bronchiectasis beginning in early childhood, and sinus disease (sometimes becoming severe in adults). However, diagnosis is often missed early in life despite the characteristic signs and symptoms.[1] In males, immotility of sperm leads to infertility, although conception remains possible through the use of in vitro fertilization.

Many affected individuals experience hearing loss and show symptoms of glue ear which demonstrate variable responsiveness to the insertion of myringotomy tubes or grommets. Some patients have been having a poor sense of smell, which is believed to accompany high mucus production in the sinuses (although others report normal - or even acute - sensitivity to smell and taste). Clinical progression of the disease is variable with lung transplantation required in severe cases. Susceptibility to infections can be drastically reduced by an early diagnosis. Treatment with various chest physiotherapy techniques has been observed to reduce the incidence of lung infection and to slow the progression of bronchiectasis dramatically. Aggressive treatment of sinus disease beginning at an early age is believed to slow long-term sinus damage (although this has not yet been adequately documented). Aggressive measures to enhance clearance of mucus, prevent respiratory infections, and treat bacterial superinfections have been observed to slow lung-disease progression. Although the true incidence of the disease is unknown, it is estimated to be 1 in 32,000,[2] although the actual incidence may be as high as 1 in 15,000.

Genetics

PCD is a genetically heterogeneous disorder affecting motile cilia[3] which are made up of approximately 250 proteins.[4] Around 90%[5] of individuals with PCD have ultrastructural defects affecting protein(s) in the outer and/or inner dynein arms which give cilia their motility, with roughly 38%[5] of these defects caused by mutations on two genes, DNAI1 and DNAH5, both of which code for proteins found in the ciliary outer dynein arm.

There is an international effort to identify genes that code for inner dynein arm proteins or proteins from other ciliary structures (radial spokes, central apparatus, etc.) associated with PCD.[citation needed] The role of DNAH5 in heterotaxy syndromes and left-right asymmetry is also under investigation.

Type OMIM Gene Locus CILD1 244400 DNAI1 9p21-p13 CILD2 606763 ? 19q13.3-qter CILD3 608644 DNAH5 5p CILD4 608646 ? 15q13 CILD5 608647 ? 16p12 CILD6 610852 TXNDC3 7p14-p13 CILD7 611884 DNAH11 7p21 CILD8 612274 ? 15q24-q25 CILD9 612444 DNAI2 17q25 CILD10 612518 KTU 14q21.3 CILD11 612649 RSPH4A 6q22 CILD12 612650 RSPH9 6p21 CILD13 613190 LRRC50 16q24.1 Pathophysiology

This disease is genetically inherited. Structures that make up the cilia including inner and/or outer dynein arms, central apparatus, radial spokes, etc. are missing or dysfunctional and thus the axoneme structure lacks the ability to move. Axonemes are the elongated structures that make up cilia and flagella. Additionally, there may be chemical defects that interfere with ciliary function in the presence of adequate structure. Whatever the underlying cause, dysfunction of the cilia begins during and impacts the embryologic phase of development.

Specialised monocilia are at the heart of this problem. They lack the central-pair microtubules of ordinary motile cilia and so rotate clockwise rather than beat; in Hensen's node at the anterior end of the primitive streak in the embryo, these are angled posteriorly[6][7] such that they prescribe a D-shape rather than a circle.[7] This has been shown to generate a net leftward flow in mouse and chick embryos, and sweeps the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) protein to the left, triggering normal asymmetrical development.

However, in some individuals with PCD, mutations thought to be in the gene coding for the key structural protein left-right dynein (lrd)[3] result in monocilia which do not rotate. There is therefore no flow generated in the node, Shh moves at random within it, and 50% of those affected develop situs inversus which can occur with or without dextrocardia, where the laterality of the internal organs is the mirror-image of normal. Affected individuals therefore have Kartagener syndrome. This is not the case with some PCD-related genetic mutations: at least 6%[citation needed] of the PCD population have a condition called situs ambiguus or heterotaxy where organ placement or development is neither typical (situs solitus) nor totally reversed (situs inversus totalis) but is a hybrid of the two. Splenic abnormalities such as polysplenia, asplenia and complex congenital heart defects are more common in individuals with situs ambiguus and PCD, as they are in all individuals with situs ambiguus.[8]

The genetic forces linking failure of nodal monocilia and situs issues and the relationship of those forces to PCD are the subject of intense research interest. For now hypotheses abound—some, like the one above, are generally accepted.[citation needed] However, knowledge in this area is constantly advancing.

Relation to other rare genetic disorders

Recent findings in genetic research have suggested that a large number of genetic disorders, both genetic syndromes and genetic diseases, that were not previously identified in the medical literature as related, may be, in fact, highly related in the genetypical root cause of the widely-varying, phenotypically-observed disorders. Thus, PCD is a ciliopathy. Other known ciliopathies include Bardet-Biedl syndrome, polycystic kidney and liver disease, nephronophthisis, Alstrom syndrome, Meckel-Gruber syndrome and some forms of retinal degeneration.[9]

History

The classic symptom combination associated with PCD was first described by A. K. Zivert[10] in 1904, while Kartagener published his first report on the subject in 1933.[11]

References

- ^ Coren, Me; Meeks, M; Morrison, I; Buchdahl, Rm; Bush, A (2002). "Primary ciliary dyskinesia: age at diagnosis and symptom history". Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992) 91 (6): 667–9. doi:10.1080/080352502760069089. PMID 12162599.

- ^ Ceccaldi PF, Carre-Pigeon F, Youinou Y, Delepine B, Bryckaert PE, Harika G, Quereux C, Gaillard D. (2004). "Kartagener's syndrome and infertility: observation, diagnosis and treatment". J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. (Paris) 33 (3): 192–4.

- ^ a b Chodhari, R; Mitchison, Hm; Meeks, M (March 2004). "Cilia, primary ciliary dyskinesia and molecular genetics". Paediatric respiratory reviews 5 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2003.09.005. PMID 15222957.

- ^ GeneReviews. "Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia". http://www.genetests.org/servlet/access?db=geneclinics&site=gt&id=8888890&key=ujnJJL1T9E6XN&gry=&fcn=y&fw=8zBM&filename=/profiles/pcd/index.html. Retrieved 2007-11-16 s.

- ^ a b Zariwala, Ma; Knowles, Mr; Omran, H (2007). "Genetic defects in ciliary structure and function". Annual review of physiology 69: 423–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141301. PMID 17059358.

- ^ Cartwright, Jh; Piro, O; Tuval, I (May 2004). "Fluid-dynamical basis of the embryonic development of left-right asymmetry in vertebrates" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (19): 7234–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402001101. PMC 409902. PMID 15118088. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15118088.

- ^ a b Nonaka, S; Yoshiba, S; Watanabe, D; Ikeuchi, S; Goto, T; Marshall, Wf; Hamada, H (August 2005). "De novo formation of left-right asymmetry by posterior tilt of nodal cilia" (Free full text). PLoS biology 3 (8): e268. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030268. PMC 1180513. PMID 16035921. http://biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0030268.

- ^ Kennedy, Mp; Omran, H; Leigh, Mw; Dell, S; Morgan, L; Molina, Pl; Robinson, Bv; Minnix, Sl; Olbrich, H; Severin, T; Ahrens, P; Lange, L; Morillas, Hn; Noone, Pg; Zariwala, Ma; Knowles, Mr (June 2007). "Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia" (Free full text). Circulation 115 (22): 2814–21. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038. PMID 17515466. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17515466.

- ^ Badano, Jose L.; Norimasa Mitsuma, Phil L. Beales, Nicholas Katsanis (September 2006). "The Ciliopathies : An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 7: 125–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. PMID 16722803. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ Zivert AK (1904). "Über einen Fall von Bronchiectasie bei einem Patienten mit situs inversus viscerum". Berliner klinische Wochenschrift. 41: 139–141.

- ^ Kartagener M (1933). "Zur Pathogenese der Bronchiektasien: Bronchiektasien bei Situs viscerum inversus". Beiträge zur Klinik der Tuberkulose. 83 (4): 489–501. doi:10.1007/BF02141468.

External links

- GeneReview/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

- http://www.pcdfoundation.org

- http://www.pcdsupport.org.uk

- http://www.med.unc.edu/cystfib/PCD.htm

- http://www.cheo.on.ca/english/9301c.shtml

- http://www.pcdforum.com/

- Kartagener's syndrome on Who Named It

- http://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/cells/ciliaandflagella/ciliaandflagella.html Cilia defined

- http://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/cells/ciliaandflagella/ciliaandflagella.html Cilia defined

- http://www.dyskinesia.be Belgian Association about Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

This article may contain some text from the public domain source "National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Rare Diseases Report FY 2001" available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/raredisrpt01.htm

Genetic disorder, organelle: Ciliopathy Structural receptor: Polycystic kidney disease

cargo: Asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia

basal body: Bardet–Biedl syndrome

mitotic spindle: Meckel syndrome

centrosome: Joubert syndromeSignaling Other/ungrouped Alström syndrome · Primary ciliary dyskinesia · Senior–Løken syndrome · Orofaciodigital syndrome 1 · McKusick–Kaufman syndrome · Autosomal recessive polycystic kidneyCategories:- Autosomal recessive disorders

- Respiratory diseases

- Cytoskeletal defects

- Ciliopathy

- Rare diseases

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.