- Edward the Confessor

-

St. Edward the Confessor

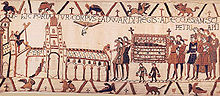

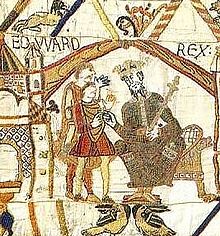

EDWARD(US) REX. Edward the Confessor enthroned , opening scene of the Bayeux Tapestry King of England Reign 8 June 1042 – 5 January 1066 Coronation 3 April 1047 Predecessor Harthacnut Successor Harold Godwinson Consort Edith of Wessex House House of Wessex Father Æthelred the Unready Mother Emma of Normandy Born c. 1003

Islip, Oxfordshire, EnglandDied 5 January 1066 (aged about 62)

London, EnglandBurial Westminster Abbey, Westminster, England Edward the Confessor also known as St. Edward the Confessor[1] (Old English: Ēadƿeard se Andettere; French: Édouard le Confesseur; 1003-05 to 4 or 5 January 1066), son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066.[2]

He has traditionally been seen as unworldly and pious, and his reign as notable for the disintegration of royal power in England and the advance in power of the Godwin family. His biographers, Frank Barlow and Peter Rex, dispute this, picturing him as a successful king, who was energetic, resourceful and sometimes ruthless, but whose reputation has been unfairly tarnished by the Norman conquest shortly after his death.[3][4] Other historians regard the picture as partly true, especially in the later part of his reign. In the view of Richard Mortimer, the return of the Godwins from exile in 1052 "meant the effective end of his exercise of power". The difference in his level of activity from the earlier part of his reign "implies a withdrawal from affairs".[5]

He had succeeded Cnut the Great's son Harthacnut, restoring the rule of the House of Wessex after the period of Danish rule since Cnut had conquered England in 1016. When Edward died in 1066 he was succeeded by Harold Godwinson, who was defeated and killed in the same year by the Normans under William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings.

Edward was canonized in 1161 by Pope Alexander III, and is commemorated on 13 October by the Catholic Church of England and Wales and the Church of England. He was regarded as one of the national saints of England until King Edward III adopted Saint George as patron saint in about 1350.[6]

Contents

Early years and exile

Attributed arms of King Edward the Confessor (who lived before standardized coats of arms came into use).

Attributed arms of King Edward the Confessor (who lived before standardized coats of arms came into use).

Penny of Edward the Confessor

Penny of Edward the Confessor

Edward was the seventh son of Æthelred, and the first by his second wife Emma, sister of Richard, Duke of Normandy. Edward was born between 1003 and 1005 in Islip, Oxfordshire,[3] and is first recorded as a 'witness' to two charters in 1005. He had one full brother, Alfred, and a sister, Godgifu. In charters he was always listed behind his older half-brothers, showing that he ranked behind them.[7]

During his childhood England was the target of Viking raids and invasions under Sweyn Forkbeard and his son, Cnut. Following Sweyn's seizure of the throne in 1013, Emma fled to Normandy, followed by Edward and Alfred, and then by Æthelred. Sweyn died in February 1014, and leading Englishmen invited Æthelred back on condition that he promised to rule 'more justly' than before. Æthelred agreed, sending Edward back with his ambassadors.[8] Æthelred died in April 1016, and he was succeeded by Edward's older half brother Edmund Ironside, who carried on the fight against Sweyn's son, Cnut. According to Scandinavian tradition, Edward fought alongside Edmund; as Edward was at most thirteen years old at the time, the story is disputed.[9][10] Edmund died in November 1016, and Cnut became undisputed king. Edward then again went into exile with his brother and sister, but his mother had no taste for the sidelines, and in 1017 she married Cnut.[3] In the same year Cnut had Edward's last surviving elder half-brother, Eadwig, executed, leaving Edward as the leading Anglo-Saxon claimant to the throne.

Edward spent a quarter of a century in exile, probably mainly in Normandy, although there is no evidence of his location until the early 1030s. He probably received support from his sister Godgifu, who married Drogo of Mantes, count of Vexin in about 1024. In the early 1030s Edward witnessed four charters in Normandy, signing two of them as king of England. According to the Norman chronicler, William of Jumièges, Robert I, Duke of Normandy attempted an invasion of England to place Edward on the throne in about 1034, but it was blown off course to Jersey. He also received support for his claim to the throne from a number of continental abbots, particularly Robert, abbot of the Norman abbey of Jumièges, who was later to become Edward's Archbishop of Canterbury.[11] Edward was said to have developed an intense personal piety during this period, but modern historians regard this as a product of the later medieval campaign for his canonisation. In Frank Barlow's view "in his lifestyle would seem to have been that of a typical member of the rustic nobility".[3][12] He appeared to have a slim prospect of acceding to the English throne during this period, and his ambitious mother was more interested in supporting Harthacnut, her son by Cnut.[3][13]

Cnut died in 1035, and Harthacnut succeeded as king of Denmark. It is unclear whether he was intended to have England as well, but he was too much occupied in defending his position there to come to England to make good any claim. It was therefore decided that his elder half-brother, Harold Harefoot should act as regent, while Emma held Wessex on Harthacnut's behalf.[14] In 1036 Edward and his brother Alfred separately came to England. Emma later claimed that they came in response to a letter inviting them to visit her which had been forged by Harold, but historians believe that she probably did invite them in an effort to counter Harold's growing popularity.[3][15] Alfred was captured by Godwin, Earl of Wessex who turned him over to Harold Harefoot. He had Alfred blinded by forcing red hot pokers into his eyes to make him unsuitable for kingship, and Alfred died soon after as a result of his wounds. The murder is thought to be the source of much of Edward's later hatred for the Earl and one of the primary reasons for Godwin's banishment in autumn 1051.[12] Edward is said to have fought a successful skirmish near Southampton, and then retreated back to Normandy.[16][17] He thus showed his prudence, but he had some reputation as a soldier in Normandy and Scandinavia.[18]

In 1037 Harold was accepted as king, and the following year he expelled Emma, who retreated to Bruges. She then summoned Edward and demanded his help for Harthacnut, but he refused as he had no resources to launch an invasion, and disclaimed any interest for himself in the throne.[3][19] Harthacnut, his position in Denmark now secure, did plan an invasion, but Harold died in 1040, and Harthacnut was able to cross unopposed with his mother to take the English throne.

In 1041, Harthacnut invited Edward back to England, probably as heir because he knew he had not long to live.[14] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Edward was sworn in as king alongside Harthacnut, but a diploma issued by Harthacnut in 1042 describes him as the king's brother.[20]

Early reign

Following Harthacnut's death on 8 June 1042, Godwin of Wessex, the most powerful of the English earls, supported Edward, who succeeded to the throne.[3] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the popularity he enjoyed at his accession — "before he [Harthacnut] was buried, all the people chose Edward as king in London." [21] Edward was crowned at the cathedral of Winchester, the royal seat of the West Saxons, on 3 April 1043.

Edward complained that his mother had "done less for him than he wanted before he became king, and also afterwards". In November 1043 he rode to Winchester with his three leading earls, Leofric of Mercia, Godwin and Siward of Northumbria, to deprive her of her property, possibly because she was holding on to treasure which belonged to the king. Her adviser, Stigand, was deprived of his bishopric of Elham in East Anglia. However, both were soon restored to favour. Emma died in 1052.[22]

Edward's position when he came to the throne was weak. Effective rule required keeping on terms with the three leading earls, but loyalty to the ancient house of Wessex had been eroded by the period of Danish rule, and only Leofric was descended from a family which had served Æthelred. Siward was probably Danish, and although Godwin was English, he was one of Cnut's new men, married to Cnut's former sister-in-law. However, in his early years Edward restored the traditional strong monarchy, showing himself, in Frank Barlow's view, "a vigorous and ambitious man, a true son of the impetuous Æthelred and the formidable Emma."[3]

In 1043 Godwin's eldest son Sweyn was appointed to an earldom in the south-west midlands, and on 23 January 1045 Edward married Godwin's daughter Edith. Soon afterwards, her brother Harold and her Danish cousin Beorn Estrithson, were also given earldoms in southern England. Godwin and his family now ruled subordinately all of southern England. However, in 1047 Sweyn was banished for abducting the Abbbess of Leominster. In 1049 he returned to try to regain his earldom, but this was said to have been opposed by Harold and Beorn, probably because they had been given Sweyn's land in his absence. Sweyn murdered his cousin Beorn and went again into exile, and Edward's nephew, Ralph was given Beorn's earldom, but the following year Sweyn's father was able to secure his reinstatement.[23]

The wealth of Edward's lands exceeded that of the greatest earls, but they were scattered among the southern earldoms. He had no personal powerbase, and he does not seem to have attempted to build one. In 1050-51 he even paid off the fourteen foreign ships which constituted his standing navy and abolished the tax raised to pay for it.[3][24] However in ecclesiastical and foreign affairs he was able to follow his own policy. King Magnus of Norway aspired to the English throne, and in 1045 and 1046, fearing an invasion, Edward took command of the fleet at Sandwich. Beorn's elder brother, Sweyn of Denmark "submitted himself to Edward as a son", hoping for his help in his battle with Magnus for control of Denmark, but in 1047 Edward rejected Godwin's demand that he send aid to Sweyn, and it was only Magnus's death in October that saved England from attack and allowed Sweyn to take the Danish throne.[3]

Modern historians reject the traditional view that Edward mainly employed Norman favourites, but he did have foreigners in his household, including a few Normans, who became unpopular. Chief among them was Robert, abbot of the Norman abbey of Jumièges, who had known Edward from the 1030s and came to England with him in 1041, becoming bishop of London in 1043. According to the Vita Edwardi, he became "always the most powerful confidential adviser to the king".[25]

The crisis of 1051-1052

In ecclesiastical appointments, Edward and his advisers showed a bias against candidates with local connections, and when the clergy and monks of Canterbury elected a relative of Godwin as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051, Edward rejected him and appointed Robert of Jumièges, who claimed that Godwin was in illegal possession of some archiepiscopal estates. In September Edward was visited by his brother-in-law, Godgifu's second husband, Eustace, count of Boulogne. His men caused an affray in Dover, and Edward ordered Godwin as earl of Kent to punish the town's burgesses, but he took their side and refused. Edward seized the chance to bring his over-mighty earl to heel. Archbishop Robert accused Godwin of plotting to kill the king, just as he had killed his brother Alfred in 1036, while Leofric and Siward supported the king and called up their vassals. Sweyn and Harold called up their own vassals, but neither side wanted a fight, and Godwin and Sweyn appear to have each given a son as hostage, who were sent to Normandy. The Godwins' position disintegrated as their men were not willing to fight the king. When Stigand, who was acting as intermediary, conveyed the king's jest that Godwin could have his peace if he could restore Alfred and his companions alive and well, Godwin and his sons fled, going to Flanders and Ireland.[3] Edward repudiated Edith and sent her to a nunnery, perhaps because she was childless,[26] and Archbishop Robert urged her divorce.[3]

Sweyn went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem (dying on his way back), but Godwin and his other sons returned with an army following a year later, and received considerable support, while Leofric and Siward failed to support the king. Both sides were concerned that a civil war would leave the country open to foreign invasion. The king was furious, but he was forced to give way and restore Godwin and Harold to their earldoms, while Robert of Jumierges and other Frenchmen fled, fearing Godwin's vengeance. Edith was restored as queen, and Stigand, who had again acted as an intermediary between the two sides in the crisis, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in Robert's place. Stigand retained his existing bishopric of Winchester, and his pluralism was to be a continuing source of dispute with the pope.[3][27] Edward's nephew, Earl Ralph, who had been one of his chief supporters in the crisis of 1051-52, may have received Sweyn's marcher earldom of Hereford at this time.[28]

Later reign

Until the mid-1050s Edward was able to structure his earldoms so as to prevent the Godwins becoming dominant. Godwin himself died in 1053 and although Harold succeeded to his earldom of Wessex, none of his other brothers were earls at this date. His house was then weaker than it had been since Edward's succession, but a succession of deaths in 1055-57 completely changed the picture. In 1055 Siward died but his son was considered too young to command Northumbria, and Harold's brother, Tostig was appointed. In 1057 Leofric and Ralph died, and Leofric's son Ælfgar succeeded as Earl of Mercia, while Harold's brother Gyrth succeeded Ælfgar as Earl of East Anglia. The fourth surviving Godwin brother, Leofwine, was given an earldom in the south-east carved out of Harold's territory, and Harold received Ralph's territory in compensation. Thus by 1057 the Godwin brothers controlled all of England subordinately apart from Mercia. It is not known whether Edward approved of this transformation or whether he had to accept it, but from this time he seems to have begun to withdraw from active politics, devoting himself to hunting, which he pursued each day after attending church.[3][29]

In the 1050s, Edward pursued an aggressive, and generally successful, policy in dealing with Scotland and Wales. Malcolm Canmore was an exile at Edward's court after Macbeth killed his father, Duncan I, and seized the Scottish throne. In 1054 Edward sent Siward to invade Scotland. He defeated Macbeth, and Malcolm, who had accompanied the expedition, gained control of southern Scotland. By 1058 Malcolm had killed Macbeth in battle and taken the Scottish throne. In 1059 he visited Edward, but in 1061 he started raiding Northumbria with the aim of adding it to his territory.[3][30]

In 1053 Edward ordered the assassination of the south Welsh prince, Rhys ap Rhydderch in reprisal for a raid on England, and Rhys's head was delivered to him.[3] In 1055 Gruffydd ap Llywelyn established himself as the ruler of all Wales, and allied with himself with Æflgar of Mercia, who had been outlawed for treason. They defeated Earl Ralph at Hereford, and Harold had to collect forces from nearly all of England to drive the invaders back into Wales. Peace was concluded with the reinstatement of Ælfgar, who was able to succeed as Earl of Mercia on his father's death in 1057. Gruffydd swore an oath to be a faithful under-king of Edward. Ælfgar appears to have died in 1062 and his young son Edwin was allowed to succeed as Earl of Mercia, but Harold then launched a surprise attack on Gruffydd. He escaped, but when Harold and Tostig attacked again the following year, he retreated and was killed by Welsh enemies. Edward and Harold were then able to impose vassallage on some Welsh princes.[31][32]

In October 1065 Harold's brother, Tostig, the earl of Northumbria, was hunting with the king when his thegns in Northumbria rebelled against his rule, which they claimed was oppressive, and killed some 200 of his followers. They nominated Morcar, the brother of Edwin of Mercia, as earl, and invited the brothers to join them in marching south. They met Harold at Northampton, and Tostig accused Harold before the king of conspiring with the rebels. Tostig seems to have been a favourite with the king and queen, who demanded that the revolt be suppressed, but neither Harold nor anyone else would fight to support Tostig. Edward was forced to submit to his banishment, and the humiliation may have caused a series of strokes which led to his death.[3][33] He was too weak to attend the dedication of his new church at Westminster, which was then still incomplete, on 28 December.

Edward probably entrusted the kingdom to Harold and Edith shortly before he died on 4 or 5 January 1066, and Harold was crowned king on 6 January, the day of Edward's burial in Westminster Abbey.[3]

The succession

Historians have puzzled over Edward's intentions for the succession since William of Malmesbury in the early twelfth century. One school of thought supports the Norman case that Edward always intended William the Conqueror to be his heir, accepting the medieval claim that Edward had already decided to be celibate before he married, but most historians believe that he hoped to have an heir by Edith at least until his quarrel with Godwin in 1051. William may have visited Edward during Godwin's exile, and he is thought to have promised William the succession at this time, but historians disagree how seriously he meant the promise, and whether he later changed his mind.[34]

Edmund Ironside's son, Edward Ætheling, had the best claim to be considered Edward's heir. He had been taken as a young child to Hungary, and in 1054 Bishop Ealdred of Worcester visited the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry III to secure his return, probably with a view to becoming Edward's heir. The exile returned to England in 1057 with his family, but died almost immediately.[35] His son Edgar, who was then about five years old, was brought up at the English court. He was given the designation Ætheling, meaning throneworthy, which may mean that Edward considered making him his heir, and he was briefly declared king after Harold's death in 1066.[36] However, Edgar was absent from witness lists of Edward's diplomas, and there is no evidence in the Domesday Book that he was a substantial landowner, which suggests that he was marginalised at the end of Edward's reign.[37]

After the mid-1050s, Edward seems to have withdrawn from affairs as he became increasingly dependent on the Godwins, and may have become reconciled to the idea that one of them would succeed him. The Normans claimed that Edward sent Harold to Normandy in about 1064 to confirm the promise of the succession to William, but this is highly implausible in view of the relative power of Edward and the Godwins at this time. The strongest evidence comes from a Norman apologist, William of Poitiers. According to his account, shortly before the Battle of Hastings, Harold sent William an envoy who admitted that Edward had promised the throne to William but argued that this was overridden by his deathbed promise to Harold. In reply, William did not dispute the deathbed promise, but argued that Edward's prior promise to him took precedence.[38]

In Richard Baxter's view, Edward's "handling of the succession issue was dangerously indecisive, and contributed to one of the greatest catastrophes to which the English have ever succumbed."[39]

Westminster Abbey

Edward's Norman sympathies are most clearly seen in the major building project of his reign, Westminster Abbey, the first Norman Romanesque church in England. This was commenced between 1042 and 1052 as a royal burial church, consecrated on 28 December 1065, completed after his death in about 1090, and demolished in 1245 to make way for Henry III's new building, which still stands. It was very similar to Jumièges Abbey, which was built at the same time. Robert of Jumièges must have been closely involved in both buildings, although it is not clear which is the original and which the copy.[40]

Edward does not appear to have been interested in books and its associated arts, but his Abbey played a vital role in the development of English Romanesque architecture, and shows that he was an innovating and generous patron of the church.[41]

Image of Edward the Confessor

Image of Edward the Confessor

The left panel of the Wilton Diptych, where Edward (centre), with Edmund the Martyr (left) and John the Baptist, are depicted presenting Richard II to the heavenly host.

The left panel of the Wilton Diptych, where Edward (centre), with Edmund the Martyr (left) and John the Baptist, are depicted presenting Richard II to the heavenly host.

Canonisation

Edward the Confessor was the first Anglo-Saxon to be canonised, and the only king of England, but he was part of a tradition of (uncanonised) English royal saints, such as Eadburh of Winchester, a daughter of Edward the Elder, Edith of Wilton, a daughter of Edgar the Peaceful, and King Edward the Martyr.[42] With his proneness to fits of rage and love of hunting Edward is regarded by most historians as an unlikely saint, and his canonisation as political, although some argue that his cult started so early that it must have had something credible to build on.[43]

Edward displayed a worldly attitude in his church appointments. When he appointed Robert of Jumièges as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051, he chose the leading craftsman Spearhafoc to replace Robert as Bishop of London. Robert refused to consecrate him, saying that the pope had forbidden it, but Spearhafoc occupied the bishopric for several months with Edward's support. After the Godwins fled the country, Edward expelled Spearhafoc, who fled with a large store of gold and gems which he had been given to make Edward a crown.[44] Stigand was the first archbishop of Canterbury not to be a monk in almost a hundred years, and he was said to have been excommunicated by several popes because he held Canterbury and Winchester in plurality. Several bishops sought consecration abroad because of the irregularity of Stigand's position.[45] Edward usually preferred clerks to monks for the most important and richest bishoprics, and he probably accepted gifts from candidates for bishoprics and abbacies. However, his appointments were generally respectable.[3]

After 1066 there was a subdued cult of Edward as a saint, possibly discouraged by the early Norman abbots of Westminster,[46] which gradually increased in the early twelfth century.[47] Osbert of Clare, the prior of Westminster Abbey, then started to campaign for Edward's canonization, aiming to increase the wealth and power of the Abbey. By 1138, he had converted the Vita Ædwardi, the life of Edward commissioned by his widow, into a conventional saint's life.[46] He seized on an ambiguous passage which might have meant that their marriage was chaste, perhaps to give the idea that Edith's childlessness was not her fault, to claim that Edward had been celibate.[48] In 1139 Osbert went to Rome to petition for Edward's canonization with the support of King Stephen, but he lacked the full support of the English hierarchy and Stephen had quarrelled with the church, so Pope Innocent II postponed a decision, declaring that Osbert lacked sufficient testimonials of Edward's holiness.[49]

In 1159 there was a disputed election to the papacy, and Henry II's support helped to secure recognition of Pope Alexander III. In 1160 a new abbot of Westminster, Laurence, seized the opportunity to renew Edward's claim. This time, it had the full support of the king and the English hierarchy, and a grateful pope issued the bull of canonization on 7 February 1161,[3] the result of a conjunction of the interests of Westminster Abbey, King Henry II and Pope Alexander III[50] He was called 'Confessor' as the name for someone who was believed to have lived a saintly life but was not a martyr or churchman.[51] In the 1230s King Henry III became attached to the cult of Saint Edward, and he commissioned a new life by Matthew Paris.[52] Henry also constructed a grand new tomb for Edward in a rebuilt Westminster Abbey in 1269.

Until about 1350, Edmund the Martyr, Gregory the Great and Edward the Confessor were regarded as English national saints, but Edward III preferred the more war-like figure of St George, and in 1348 he established the Order of the Garter with St George as its patron. It was located at Windsor Castle, and its chapel of St Edward the Confessor was re-dedicated to St George, who was acclaimed in 1351 as patron of the English race.[6] Edward was never a popular saint, but he was important to the Norman dynasty, which claimed to be the successor of Edward as the last legitimate Anglo-Saxon king.[53]

The shrine of Saint Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey remains where it was after the final translation of his body to a chapel east of the sanctuary on 13 October 1269 by Henry III.[54] The day of his translation, 13 October (his first translation had also been on that date in 1163), is regarded as his feast day, and each October the Abbey holds a week of festivities and prayer in his honour.[55] For some time the Abbey had claimed that it possessed a set of coronation regalia that Edward had left for use in all future coronations. Following Edward's canonization, these were regarded as holy relics, and thereafter they were used at all English coronations from the 13th Century until the destruction of the regalia by Oliver Cromwell in 1649.[56]

13 October is an optional feast day for Edward the Confessor for the Catholic Church of England and Wales,[57] and the Church of England's calendar of saints designates it as a Lesser Festival.[58] He is regarded as one of the patron saints of difficult marriages.[59]

In popular culture

Edward is depicted as the central saint of the Wilton Diptych (c. 1395–99), a devotional piece made for Richard II, but now in the collection of the National Gallery. The reverse of the piece carries Edward's arms; and Richard's badge of a white hart. The panel painting dates from the end of the 14th century.

In Act 3, Scene VI of Shakespeare's Macbeth (c. 1603-06) Lennox refers to Edward as "the most pious Edward," and in Act 4, Scene III, Malcolm describes his powers of healing those afflicted with "The evil," or scrofula.

He is the central figure in Alfred Duggan's 1960 historical novel The Cunning of the Dove.

He is featured in Sara Douglass' novel God's Concubine.

On screen he has been portrayed by Eduard Franz in the film Lady Godiva of Coventry (1955), George Howe in the BBC TV drama series Hereward the Wake (1965), Donald Eccles in the two-part BBC TV play Conquest (1966; part of the series Theatre 625), Brian Blessed in Macbeth (1997), based on the Shakespeare play (although he does not appear in the play itself), and Adam Woodroffe in an episode of the British TV series Historyonics entitled "1066" (2004). In 2002, he was portrayed by Lennox Greaves in the Doctor Who audio adventure Seasons of Fear.

See also

- Encomium Emmae Reginae, encomium to Edward's mother

- Vita Ædwardi Regis, life commissioned by Edward's wife

- Játvarðar Saga, Icelandic saga about the king

- List of monarchs of Wessex

- St Edward's Crown

References

- ^ The numbering of English monarchs starts anew after the Norman conquest, which explains why the regnal numbers assigned to English kings named Edward begin with the later Edward I of England and do not include Edward the Confessor (who was the third King Edward).

- ^ Edgar the Aetheling was proclaimed king after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, but never ruled and was deposed after about eight weeks.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Frank Barlow, Edward the Confessor, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Peter Rex, King and Saint: The Life of Edward the Confessor, The History Press, 2008, p. 224.

- ^ Mortimer, Edward the Confessor, p. 29.

- ^ a b Henry Summerson, Saint George, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Simon Keynes, 'Edward the Ætheling', in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor, p. 49.

- ^ Rex, op. cit., pp. 13, 19

- ^ Barlow, Frank (University of California Press). Edward the Confessor. Berkeley, CA: 1970. pp. 29–36. ISBN 0520016718.

- ^ Keynes, op. cit., p. 56 n.

- ^ Elisabeth van Houts, 'Edward and Normandy', in Mortimer ed., pp. 63-75.

- ^ a b Howarth, David (1981). 1066: The Year of the Conquest. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. ISBN 0140058508.

- ^ Rex, op. cit., p. 28

- ^ a b M. K. Lawson, Harthcnut, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Rex, op. cit., pp. 34-35

- ^ Barlow, op. cit., pp. 44-45

- ^ Pauline Stafford believes that Edward joined his mother at Winchester and returned to the continent after his brother's death. Queen Emma & Queen Edith, Blackwell, 2001, pp. 239-240

- ^ Rex, op. cit., p. 33

- ^ Rex, op. cit., p. 33

- ^ Mortimer, p. 7, Stephen Baxter, 'Edward the Confessor and the Succession Question, p. 101, in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (MS E) s.a. 1041 (1042), tr. Michael Swanton.

- ^ Rex, op. cit., pp. 48-49.

- ^ Mortimer ed., maps between pages 116 and 117

- ^ Mortimer op. cit., pp. 26-28

- ^ Van Houts, p. 69. Richard Gem, 'Craftsmen and Administrators in the Building of the Abbey', p. 171. Both in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor. Robert of Jumièges is usually described as Norman, but his origin was is unknown, possibly Frankish (Van Houts, p. 70).

- ^ Ann Williams, 'Edith' (d.1075), Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Rex, op. cit., p. 107

- ^ Ann Williams, Ralph the Timid, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004 However, Frank Barlow in his DNB article on Edward, states that Ralph received Hereford on Sweyn's first expulsion in 1047.

- ^ Baxter in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor, pp. 103-104

- ^ G. W. S. Barrow, Malcolm III, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2008

- ^ David Walker, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Ann Williams, Ælfgar, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ William M. Aird, Tostig, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Historians' views are discussed in Stephen Baxter, 'Edward the Confessor and the Succession Question', pp. 77-118, in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor, which this section is based on.

- ^ Baxter, pp. 96-98

- ^ Nicholas Hooper, Edgar Ætheling, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Baxter, pp. 98-103

- ^ Baxter, pp. 103-114

- ^ Baxter, p. 118

- ^ Eric Fernie, 'Edward the Confessor's Westminster Abbey', in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor, pp. 139-143

- ^ Mortimer, op. cit., p. 23

- ^ Edina Bozoky, 'The Sanctity and Canonisation of Edward the Confessor', in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor, pp. 178-179

- ^ Mortimer, op. cit., pp. 29-32

- ^ John Blair, 'Spearhafoc', Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ H. E. J. Cowdrey, Stigand, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ a b Frank Barlow, Osbert of Clare, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ^ Rex, op. cit., pp. 214-217

- ^ Stephen Baxter, 'Edward the Confessor and the Succession Question', in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor, pp. 84-85

- ^ Bozoky, op. cit., pp. 180-181

- ^ Bozoky, op. cit., p. 173

- ^ Rex, op. cit., p. 226

- ^ Abstract of David Carpenter, King Henry III and Saint Edward the Confessor: The Origins of the Cult, English Historical Review, CXXII (498): 865-891, 2007

- ^ Bozoky, op. cit., pp. 180-182

- ^ Edward the Confessor, Westminster Abbey

- ^ Worship at the Abbey, Westminster Abbey

- ^ Keay, A. (2002). The Crown Jewels. London: The Historic Royal Palaces. ISBN 187399320X.

- ^ Liturgy Office, England & Wales: Liturgical Calendar

- ^ Holy Days, The Church of England

- ^ patrons of difficult marriages, Saints.SPQN.com

Bibliography

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, tr. Michael Swanton, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. 2nd ed. London, 2000.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Life of St. Edward the Confessor, translated Fr. Jerome Bertram (first English translation) St. Austin Press ISBN 1-901157-75-X

- Barlow, Frank, Edward the Confessor, Oxford University Press, 1997

- Barlow, Frank, Edward (St Edward; known as Edward the Confessor), Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- Mortimer, Richard ed., Edward the Confessor: The Man and the Legend, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2009 ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6

- O'Brien, Bruce R.: God's peace and king's peace : the laws of Edward the Confessor, Philadelphia, Pa. : University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8122-3461-8

- The Life of King Edward who rests at Westminster (Vita Ædwardi Regis) ed. and trans. Frank Barlow, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992

- Rex, Peter, King & Saint: The Life of Edward the Confessor, The History Press, Stroud, 2008

- The Waltham Chronicle ed. and trans. Leslie Watkiss and Marjorie Chibnall, Oxford Medieval Texts, OUP, 1994

- William of Malmesbury, The History of the English Kings, i, ed.and trans. R.A.B. Mynors, R.M.Thomson and M.Winterbottom, Oxford Medieval Texts, OUP 1998

External links

Media related to Edward the Confessor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Edward the Confessor at Wikimedia Commons- Westminster Abbey: Edward the Confessor and Edith

- Steven Muhlberger's 'Edward the Confessor and his earls'

- Illustrated biography of Edward the Confessor

- BBC History: Edward the Confessor

- The Rise of Godwine, Earl of Wessex

- Edward the Confessor At Find A Grave

- BBC News: Ancient royal tomb is uncovered

Preceded by

HarthacnutKing of the English

1043–1066Succeeded by

Harold IISaints of Anglo-Saxon England British / Welsh / Irish Alban of St Albans · Aldatus of Oxford · Amphibalus of St Albans · Arilda of Oldbury · Barloc of Norbury · Brannoc of Braunton · Branwalator of Milton · Credan of Bodmin · Congar of Congresbury · Dachuna of Bodmin · Decuman of Watchet · Elfin of Warrington · Ivo of Ramsey · Judoc of Winchester · Juthwara of Sherbourne · Melorius of Amesbury · Nectan of Hartland · Neot of St Neots · Patrick of Glastonbury · Rumon of Tavistock · Samson of Dol · Sativola of Exeter · Urith of Chittlehampton

East Anglian Æthelberht of East Anglia · Æthelburh of Faremoutiers · Æthelflæd of Ramsey · Æthelthryth of Ely · Æthelwine of Lindsey · Athwulf of Thorney · Blitha of Martham · Botwulf of Thorney · Cissa of Crowland · Cuthbald of Peterborough · Eadmund of East Anglia · Eadnoth of Ramsey · Guthlac of Crowland · Herefrith of Thorney · Hiurmine of Blythburgh · Huna of Thorney · Pega of Peakirk · Regenhere of Northampton · Seaxburh of Ely · Tancred of Thorney · Torthred of Thorney · Tova of Thorney · Walstan of Bawburgh · Wihtburh of Ely · Wulfric of Holme

East Saxon Æthelburh of Barking · Hildelith of Barking · Osgyth · Sæbbi of London

Frisian,

Frankish

and Old SaxonBalthild of Romsey · Bertha of Kent · Felix of Dommoc · Grimbald of St Bertin · Monegunda of Watton · Odwulf of Evesham · Wulfram of Grantham

Irish and Scottish Aidan of Lindisfarne · Boisil of Melrose · Echa of Crayke · Ultan the Scribe · Indract of Glastonbury · Maildub of Malmesbury

Kentish Æbbe of Thanet · Æthelberht of Kent · Æthelburh of Kent · Æthelred of Kent · Albinus of Canterbury · Berhtwald of Canterbury · Deusdedit of Canterbury · Eadburh of Thanet · Eanswith of Folkestone · Eormengyth of Thanet · Nothhelm of Canterbury · Sigeburh of Thanet

Mercian Ælfnoth of Stowe · Ælfthryth of Crowland · Æthelberht of Bedford · Æthelmod of Leominster · Æthelred of Mercia · Æthelwine of Coln · Æthelwynn of Sodbury · Beonna of Breedon · Beorhthelm of Stafford · Coenwulf of Mercia · Cotta of Breedon · Credan of Evesham · Cyneburh of Castor · Cyneburh of Gloucester · Kenelm of Winchcombe · Cyneswith of Peterborough · Eadburh of Bicester · Eadburh of Pershore · Eadburh of Southwell · Eadgyth of Aylesbury · Eadweard of Maugersbury · Ealdgyth of Stortford · Earconwald of London · Ecgwine of Evesham · Freomund of Mercia · Frithuric of Breedon · Frithuswith of Oxford · Frithuwold of Chertsey · Hæmma of Leominster · Merefin · Mildburh of Wenlock · Mildgyth · Mildthryth of Thanet · Milred of Worcester · Oda of Canterbury · Oswald of Worcester · Osburh of Coventry · Rumwold of Buckingham · Tibba of Ryhall · Werburh of Chester · Wærstan · Wigstan of Repton · Wulfhild of Barking

Northumbrian Acca of Hexham · Æbbe "the Elder" of Coldingham · Æbbe "the Younger" of Coldingham · Ælfflæd of Whitby · Ælfwald of Northumbria · Æthelburh of Hackness · Æthelgyth of Coldingham · Æthelsige of Ripon · Æthelwold of Farne · Æthelwold of Lindisfarne · Alchhild of Middleham · Alchmund of Hexham · Alchmund of Derby · Balthere of Tyningham · Beda of Jarrow · Bega of Copeland · Benedict Biscop · Bercthun of Beverley · Billfrith of Lindisfarne · Bosa of York · Botwine of Ripon · Ceadda of Lichfield · Cedd of Lichfield · Ceolfrith of Monkwearmouth · Ceolwulf of Northumbria · Cuthbert of Durham · Dryhthelm of Melrose · Eadberht of Lindisfarne · Eadfrith of Leominster · Eadfrith of Lindisfarne · Eadwine of Northumbria · Ealdberht of Ripon · Eanmund · Eardwulf of Northumbria · Eata of Hexham · Ecgberht of Ripon · Eoda · Eosterwine of Monkwearmouth · Hilda of Whitby · Hyglac · Iwig of Wilton · John of Beverley · Osana of Howden · Osthryth of Bardney · Oswald of Northumbria · Oswine of Northumbria · Sicgred of Ripon · Sigfrith of Monkwearmouth · Tatberht of Ripon · Wihtberht of Ripon · Wilfrith of Hexham · Wilfrith II · Wilgisl of Ripon

Roman Augustine of Canterbury · Firmin of North Crawley · Birinus of Dorchester · Blaise · Florentius of Peterborough · Hadrian of Canterbury · Honorius of Canterbury · Justus of Canterbury · Laurence of Canterbury · Mellitus of Canterbury · Paulinus of York · Theodore of Canterbury

South Saxon Cuthflæd of Lyminster · Cuthmann of Steyning · Leofwynn of Bishopstone

West Saxon Æbbe of Abingdon · Ælfgar of Selwood · Ælfgifu of Exeter · Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury · Ælfheah of Canterbury · Ælfheah of Winchester · Æthelflæd of Romsey · Æthelgar of Canterbury · Æthelnoth of Canterbury · Æthelwine of Athelney · Æthelwold of Winchester · Aldhelm of Sherbourne · Benignus of Glastonbury · Beocca of Chertsey · Beorhthelm of Shaftesbury · Beornstan of Winchester · Beornwald of Bampton · Centwine of Wessex · Cuthburh of Wimborn · Cwenburh of Wimborne · Dunstan of Canterbury · Eadburh of Winchester · Eadgar of England · Eadgyth of Polesworth · Eadgyth of Wilton · Eadweard the Confessor · Eadweard the Martyr · Eadwold of Cerne · Earmund of Stoke Fleming · Edor of Chertsey · Evorhilda · Frithestan of Winchester · Hædde of Winchester · Humbert of Stokenham · Hwita of Whitchurch Canonicorum · Mærwynn of Romsey · Margaret of Dunfermline · Swithhun of Winchester · Wulfsige of Sherborne · Wulfthryth of Wilton

Unclear origin Rumbold of Mechelen

English monarchs Kingdom of the

English

886–1066- Alfred the Great

- Edward the Elder

- Ælfweard

- Athelstan the Glorious1

- Edmund the Magnificent1

- Eadred1

- Eadwig the Fair1

- Edgar the Peaceable1

- Edward the Martyr

- Æthelred the Unready

- Sweyn Forkbeard

- Edmund Ironside

- Cnut1

- Harold Harefoot

- Harthacnut

- Edward the Confessor

- Harold Godwinson

- Edgar the Ætheling

Kingdom of

England

1066–1649- William I

- William II

- Henry I

- Stephen

- Matilda

- Henry II2

- Henry the Young King

- Richard I

- John2

- Henry III2

- Edward I2

- Edward II2

- Edward III2

- Richard II2

- Henry IV2

- Henry V2

- Henry VI2

- Edward IV2

- Edward V2

- Richard III2

- Henry VII2

- Henry VIII2

- Edward VI2

- Jane2

- Mary I2 with Philip2

- Elizabeth I2

- James I3

- Charles I3

Commonwealth of

England, Scotland and Ireland

1653–1659Kingdom of

England

1660–1707- Charles II3

- James II3

- William III and Mary II3

- Anne3

1Overlord of Britain. 2Also ruler of Ireland. 3Also ruler of Scotland. 4Lord Protector.

Debatable or disputed rulers are in italics.Categories:- Anglo-Saxon monarchs

- Anglo-Saxon saints

- English monarchs

- English Roman Catholic saints

- Anglican saints

- Catholic monarchs

- Norman conquest of England

- People from Cherwell (district)

- 1000s births

- 1066 deaths

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- People associated with Westminster Abbey

- 11th-century English people

- 11th-century Christian saints

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.