- La bohème

-

For Ruggero Leoncavallo's opera of the same name, see La bohème (Leoncavallo). For other uses, see La bohème (disambiguation).

Giacomo Puccini  Operas

Operas- Le Villi (1884)

- Edgar (1889)

- Manon Lescaut (1893)

- La bohème (1896)

- Tosca (1900)

- Madama Butterfly (1904)

- La fanciulla del West (1910)

- La rondine (1917)

- Il trittico (1918)

- Turandot (completed 1926 by Alfano)

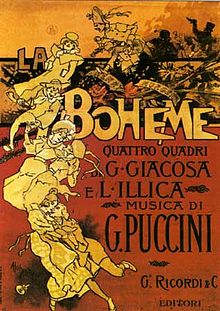

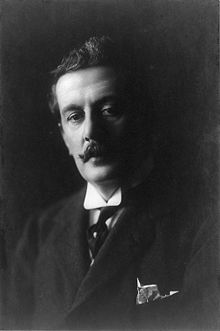

La bohème is an opera in four acts,[N 1] by Giacomo Puccini to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, based on Scènes de la vie de bohème by Henri Murger.[1] The world premiere performance of La bohème was in Turin on 1 February 1896 at the Teatro Regio[2] and conducted by the young Arturo Toscanini. Since then, La bohème has become part of the standard Italian opera repertory and is one of the most frequently performed operas internationally. According to Operabase, it is the fourth most frequently performed opera worldwide.[3] In 1946, fifty years after the opera's premiere, Toscanini conducted a performance of it on radio with the NBC Symphony Orchestra. This performance was eventually released on records and on Compact Disc. It is the only recording of a Puccini opera by its original conductor (see Recordings below).

Contents

Origin of the story

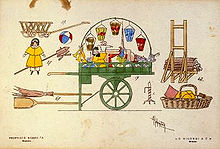

Mimì's costume for act 1 of La bohème designed by Adolfo Hohenstein for the world premiere

Mimì's costume for act 1 of La bohème designed by Adolfo Hohenstein for the world premiere

According to its title page, the libretto of La bohème is based on Henri Murger's novel, Scènes de la vie de bohème, a collection of vignettes portraying young bohemians living in the Latin Quarter of Paris in the 1840s. Although usually called a novel, it has no unified plot. Like the 1849 play by Murger and Théodore Barrière, the opera's libretto focuses on the relationship between Rodolfo and Mimì, ending with her death. Also like the play, the libretto combines two characters from the novel, Mimì and Francine, into a single Mimì character.

Much of the libretto is original. The main plots of acts two and three are the librettists' invention, with only a few passing references to incidents and characters in Murger. Most of acts one and four follow the novel, piecing together episodes from various chapters. The final scenes in acts one and four —the scenes with Rodolfo and Mimì— resemble both the play and the novel. The story of their meeting closely follows chapter 18 of the novel, in which the two lovers living in the garret are not Rodolphe and Mimì at all, but rather Jacques and Francine. The story of Mimì's death in the opera draws from two different chapters in the novel, one relating Francine's death and the other relating Mimì's.[1]

The published libretto includes a note from the librettists briefly discussing their adaptation. Without mentioning the play directly, they defend their conflation of Francine and Mimì into a single character: "Chi puo non confondere nel delicato profilo di una sola donna quelli di Mimì e di Francine?" ("Who cannot detect in the delicate profile of one woman the personality both of Mimì and of Francine?") At the time, the novel was in the public domain, Murger having died without heirs, but rights to the play were still controlled by Barrière's heirs.[4]

Performance history

Initial success

The world première performance of La bohème took place in Turin on 1 February 1896 at the Teatro Regio[2] and was conducted by the young Arturo Toscanini. The opera quickly became popular throughout Italy and productions were soon mounted by the following companies: The Teatro di San Carlo (14 March 1896, with Elisa Petri as Musetta and Antonio Magini-Coletti as Marcello); The Teatro Comunale di Bologna (4 November 1896, with Amelia Sedelmayer as Musetta and Umberto Beduschi as Rodolfo); The Teatro Costanzi (17 November 1896, with Maria Stuarda Savelli as Mimì, Enrico Giannini-Grifoni as Rodolfo, and Maurizio Bensaude as Marcello); La Scala (15 March 1897, with Angelica Pandolfini as Mimì, Camilla Pasini as Musetta, Fernando De Lucia as Rodolfo, and Edoardo Camera as Marcello); La Fenice (26 December 1897, with Emilia Merolla as Mimì, Maria Martelli as Musetta, Giovanni Apostolu and Franco Mannucci as Rodolfo, and Ferruccio Corradetti as Marcello); Teatro Regio di Parma (29 January 1898, with Solomiya Krushelnytska as Mimì, Lina Cassandro as Musetta, Pietro Ferrari as Rodolfo, and Pietro Giacomello as Marcello); And the Teatro Donizetti di Bergamo (21 August 1898, with Emilia Corsi as Mimì, Annita Barone as Musetta, Giovanni Apostolu as Rodolfo, and Giovanni Roussel as Marcello).[5]

The first performance of La bohème outside Italy was at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 16 June 1896. The opera was given in Alexandria, Lisbon, and Moscow in early 1897. The United Kingdom premiere took place at the Theatre Royal in Manchester, on 22 April 1897, in a presentation by the Carl Rosa Opera Company supervised by Puccini.[6] This performance was given in English and starred Alice Esty as Mimì, Bessie McDonald as Musetta, Robert Cunningham as Rodolfo, and William Paull as Marcello.[6] On 2 October 1897 the same company gave the opera's first staging at the Royal Opera House in London and on 14 October 1897 in Los Angeles for the opera's United States premiere. The opera reached New York City on 16 May 1898 when it was performed at Palmo's Opera House with Giuseppe Agostini as Rodolfo. The first production of the opera actually produced by the Royal Opera House itself premiered on 1 July 1899 with Nellie Melba as Mimì, Zélie de Lussan as Musetta, Fernando De Lucia as Rodolfo, and Mario Ancona as Marcello.[5]

La bohème premiered in Germany at the Kroll Opera House in Berlin on 22 June 1897. The French premiere of the opera was presented by the Opéra-Comique on 13 June 1898 at the Théâtre des Nations. The production used a French translation by Paul Ferrier and starred Julia Guiraudon as Mimì, Jeanne Tiphaine as Musetta, Adolphe Maréchal as Rodolfo, and Lucien Fugère as Marcello.[5] The Czech premiere of the opera was presented by the National Theatre on 27 February 1898.

20th century

La bohème continued to gain international popularity throughout the early 20th century and the Opéra-Comique alone had already presented the opera one hundred times by 1903. The Belgian premiere took place at La Monnaie on 25 October 1900 using Ferrier's French translation with Marie Thiérry as Mimì, Léon David as Rodolfo, Eugène-Charles Badiali as Marcello, sets by Pierre Devis, Armand Lynen, and Albert Dubosq, and Philippe Flon conducting. The Metropolitan Opera staged the work for the first time on 26 December 1900 with Nellie Melba as Mimì, Annita Occhiolini-Rizzini as Musetta, Albert Saléza as Rodolfo, Giuseppe Campanari as Marcello, and Luigi Mancinelli conducting.[5]

The opera was first presented in Brazil at the Teatro Amazonas in Manaus on 2 July 1901 with Elvira Miotti as Mimì, Mabel Nelma as Musetta, Michele Sigaldi as Rodolfo, and Enrico De Franceschi as Marcello. Other premieres soon followed:

- Melbourne: 13 July 1901 (Her Majesty's Theatre; first performance in Australia)[7]

- Monaco: 1 February 1902, Opéra de Monte-Carlo in Monte Carlo with Nellie Melba as Mimì, Enrico Caruso as Rodolfo, Alexis Boyer as Marcello, and Léon Jehin conducting.[5]

- Prato: 25 December 1902, Regio Teatro Metastasio with Ulderica Persichini as Mimì, Norma Sella as Musetta, Ariodante Quarti as Rodolfo, and Amleto Pollastri as Marcello.[5]

- Catania: 9 July 1903, Politeama Pacini with Isabella Costa Orbellini as Mimì, Lina Gismondi as Musetta, Elvino Ventura as Rodolfo, and Alfredo Costa as Marcello.[5]

- Austria: 25 November 1903, Vienna State Opera in Vienna with Selma Kurz as Mimì, Marie Gutheil-Schoder as Musetta, Fritz Schrödter as Rodolfo, Gerhard Stehmann as Marcello, and Gustav Mahler conducting.[5]

- Sweden: 19 May 1905, Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm, presented by the Royal Swedish Opera with Maria Labia as Mimì.[5]

Roles

Role Voice type Premiere cast, 1 February 1896

(Conductor: Arturo Toscanini)Rodolfo, a poet tenor Evan Gorga Mimì, a seamstress soprano Cesira Ferrani Marcello, a painter baritone Tieste Wilmant Musetta, a singer soprano Camilla Pasini Schaunard, a musician baritone Antonio Pini-Corsi Colline, a philosopher bass Michele Mazzara Benoît, their landlord bass Alessandro Polonini Alcindoro, a state councillor bass Alessandro Polonini Parpignol, a toy vendor tenor Dante Zucchi A customs Sergeant bass Felice Fogli Students, working girls, townsfolk, shopkeepers, street-vendors, soldiers, waiters, children Synopsis

The story is set in Paris in the period around 1830.[8]

It essentially focuses on the love between the seamstress called Mimì and the poet Rodolfo. They almost immediately fall in love with each other, but Rodolfo later wants to leave Mimì because of her flirtatious behavior. However, Mimì also happens to be mortally ill, and Rodolfo also feels guilt, since their life together likely had worsened her health even further. They reunite for a brief moment at the end before Mimì dies.

Act 1

In the four bohemians' garret

Marcello is painting while Rodolfo gazes out of the window. In order to keep warm, they burn the manuscript of Rodolfo's drama. Colline, the philosopher, enters shivering and disgruntled at not having been able to pawn some books. Schaunard, the musician of the group, arrives with food, firewood, wine, cigars, and money, and he explains the source of his riches, a job with an eccentric English gentleman. The others hardly listen to his tale as they fall ravenously upon the food. Schaunard interrupts them by whisking the meal away and declaring that they will all celebrate his good fortune by dining at Cafe Momus instead.

While they drink, Benoît, the landlord, arrives to collect the rent. They flatter him and ply him with wine. In his drunkenness, he recites his amorous adventures, but when he also declares he is married, they thrust him from the room —without the rent payment— in comic moral indignation. The rent money is divided for their carousal in the Quartier Latin.

The other Bohemians go out, but Rodolfo remains alone for a moment in order to finish an article he is writing, promising to join his friends soon. There is a knock at the door, and Mimì, a seamstress who lives in another room in the building, enters. Her candle has blown out, and she has no matches; she asks Rodolfo to light it. She thanks him, but returns a few seconds later, saying she has lost her key. Both candles are extinguished; the pair stumble in the dark. Rodolfo, eager to spend time with Mimì, finds the key and pockets it, feigning innocence. In two arias (Rodolfo's Che gelida manina – "What a cold little hand" and Mimì's Sì, mi chiamano Mimì – "Yes, they call me Mimì"), they tell each other about their different backgrounds. Impatiently, the waiting friends call Rodolfo, but, while he suggests remaining at home with Mimì, she decides to accompany him. As they leave, they sing of their newfound love (duet, Rodolfo and Mimì: O soave fanciulla – "Oh gentle maiden").

Act 2

Quartier Latin

A great crowd, along with children, has gathered with street sellers announcing their wares (chorus: Aranci, datteri! Caldi i marroni! – "Oranges, dates! Hot chestnuts!"). The friends appear, flushed with gaiety; Rodolfo buys Mimì a bonnet from a vendor. Parisians gossip with friends and bargain with the vendors; the children of the streets clamor to see the wares of Parpignol, the toy seller. The friends enter the Cafe Momus.

As the men and Mimì dine at the cafe, Musetta, formerly Marcello's sweetheart, arrives with her rich (and aging) government minister admirer, Alcindoro, to whom she speaks as she might to a lapdog. It is clear she has tired of him. To the delight of the Parisians and the embarrassment of her patron, she sings a risqué song (Musetta's waltz: Quando me'n vo' – "When I go along"), hoping to reclaim Marcello's attention. Soon Marcello is burning with jealousy. To be rid of Alcindoro for a bit, Musetta pretends to be suffering from a tight shoe and sends him with it to the shoemaker to be fixed. During the melee that follows, Musetta and Marcello fall into each other's arms and reconcile.

The friends are presented with the bill and to their consternation find that Schaunard's money is not enough to pay it. The sly Musetta has the entire bill charged to Alcindoro. The sound of approaching soldiers is heard, and, picking up Musetta, Marcello and Colline carry her out on their shoulders amid the applause of the spectators. When all have gone, Alcindoro arrives with the repaired shoe seeking Musetta. The waiter hands him the bill, and, horror-stricken at the charge, Alcindoro sinks into a chair.

Act 3

At the toll gate

Peddlers pass through the barriers and enter the city. Amongst them is Mimì, coughing violently. She tries to find Marcello, who lives in a little tavern nearby where he paints signs for the innkeeper. She tells him of her hard life with Rodolfo, who has abandoned her that night (O buon Marcello, aiuto! – "Oh, good Marcello, help me!"). Marcello tells her that Rodolfo is asleep inside, but he wakes up and comes out looking for Marcello. Mimì hides and overhears Rodolfo first telling Marcello that he left Mimì because of her coquettishness, but finally confessing that he fears she is slowly being consumed by a deadly illness (most likely tuberculosis, known by the catchall name "consumption" in the nineteenth century). Rodolfo, in his poverty, can do little to help Mimì and hopes that his pretended unkindness will inspire her to seek another, wealthier suitor (Marcello, finalmente – "Marcello, finally"). Out of kindness towards Mimì, Marcello tries to silence him, but she has already heard all. Her coughing reveals her presence, and Rodolfo and Mimì sing of their lost love. They make plans to separate amicably (Mimì: Donde lieta uscì – "From here she happily left"), but their love for one another is too strong. As a compromise, they agree to remain together until the spring, when the world is coming to life again and no one feels truly alone. Meanwhile, Marcello has joined Musetta, and the couple quarrel fiercely: an antithetical counterpoint to the other pair's reconciliation (quartet: Mimì, Rodolfo, Musetta, Marcello: Addio dolce svegliare alla mattina! – "Goodbye, sweet awakening in the morning!").

Act 4

Back in the garret

Marcello and Rodolfo are seemingly at work, though they are primarily bemoaning the loss of their respective loves (duet: O Mimì, tu più non torni – "O Mimì, will you not return?"). Schaunard and Colline arrive with a very frugal dinner and all parody eating a plentiful banquet, dance together, and sing. Musetta arrives with news: Mimì, who took up with a wealthy viscount after leaving Rodolfo in the spring, has left her patron. Musetta has found her wandering the streets, severely weakened by her illness, and has brought her back to the garret. Mimì, haggard and pale, is assisted into a chair. Musetta and Marcello leave to sell Musetta's earrings in order to buy medicine, and Colline leaves to pawn his overcoat (Vecchia zimarra – "Old coat"). Schaunard, urged by Colline, quietly departs to give Mimì and Rodolfo time together. Left alone, they recall their past happiness (duet, Mimì and Rodolfo: Sono andati? – "Have they gone?"). They relive their first meeting —the candles, the lost key— and, to Mimì's delight, Rodolfo presents her with the pink bonnet he bought her, which he has kept as a souvenir of their love. The others return, with a gift of a muff to warm Mimì's hands and some medicine. They tell Rodolfo that a doctor has been summoned, but Mimì lapses into unconsciousness. As Musetta prays, Mimì dies. Schaunard discovers Mimì lifeless. Rodolfo cries Mimì's name in anguish, and weeps helplessly.

Instrumentation

La bohème is scored for:

- woodwind: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, cor anglais, 2 clarinets in A and B flat, bass clarinet in A and B flat, 2 bassoons

- brass: 4 horns in F, 3 trumpets in F, 3 trombones, bass trombone

- Percussion: timpani, snare drum, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, xylophone, glockenspiel, chimes

- strings: harp, violins I, II, viola, cello, double bass

Recording history

Main article: La bohème discographyThe discography of La bohème is a long one with many distinguished recordings, including the 1973 RCA Victor conducted by Sir Georg Solti with Montserrat Caballé as Mimì and Plácido Domingo as Rodolfo which won the 1974 Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording. The earliest commercially released full-length recording was probably that recorded in February 1917 and released on the Italian label La Voce del Padrone.[9] Carlo Sabajno conducted the La Scala Orchestra and Chorus with Gemma Bosini and Remo Andreini as Mimì and Rodolfo. One of the most recent is the 2008 Deutsche Grammophon release conducted by Bertrand de Billy with Anna Netrebko and Rolando Villazón as Mimì and Rodolfo.

There are several recordings with conductors closely associated with Puccini. In the 1946 RCA Victor release, Arturo Toscanini, who conducted the world premiere of the opera, conducts the NBC Symphony Orchestra with Jan Peerce as Rodolfo and Licia Albanese as Mimì. It is the only recording of a Puccini opera by its original conductor. Thomas Beecham, who worked closely with Puccini when preparing a 1920 production of La bohème in London,[10] conducted a performance of the opera in English released by Columbia Records in 1936 with Lisa Perli as Mimì and Heddle Nash as Rodolfo. Beecham also conducts on the 1956 RCA Victor recording with Victoria de los Ángeles and Jussi Björling as Mimì and as Rodolfo.

Although the vast majority of recordings are in the original Italian, the opera has been recorded in several other languages. These include: a recording in French conducted by Erasmo Ghiglia with Renée Doria and Alain Vanzo as Mimì and Rodolfo (1960);[11] a recording in German with Richard Kraus conducting the Deutsche Oper Berlin Orchestra and Chorus with Trude Eipperle and Fritz Wunderlich as Mimì and Rodolfo (1956); and the 1998 release on the Chandos Opera in English label with David Parry conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra and Cynthia Haymon and Dennis O'Neill as Mimì and Rodolfo.

Enrico Caruso, who was closely associated with the role of Rodolfo, never recorded a full version of the opera but recorded several extracts beginning with one on cylinder in 1906. Rodolfo's famous aria "Che gelida manina" was recorded not only by Caruso but by nearly 500 other tenors in at least seven different languages between 1900 and 1980.[12] In 1981 the A.N.N.A. Record Company released a six LP set with 101 different tenors singing the aria.

The missing act

In 1957 Illica’s widow died and his papers were given to the Parma Museum. Among them was the full libretto to La bohème. It was discovered that the librettists had prepared an act which Puccini decided not to use in his composition.[13] It is noteworthy for explaining Rodolfo’s jealous remarks to Marcello in act 3.

The "missing act" is located in the timeline between the Café Momus scene and act 3 and describes an open-air party at Musetta’s dwelling. Her protector has refused to pay further rent out of jealous feelings, and Musetta’s furniture is moved into the courtyard to be auctioned off the following morning. The four Bohemians find in this an excuse for a party and arrange for wine and an orchestra. Musetta gives Mimì a beautiful gown to wear and introduces her to a Viscount. The pair dances a quadrille in the courtyard, which moves Rodolfo to jealousy. This explains his act 3 reference to the "moscardino di Viscontino" (young fop of a Viscount). As dawn approaches, furniture dealers gradually remove pieces for the morning auction.

Derivative works

In 1959 "Musetta's Waltz" was adapted by songwriter Bobby Worth for the 1959 pop song "Don't You Know?", a hit for Della Reese.[14] The opera was also adapted into a 1983 short story form by the novelist V. S. Pritchett for publication by the Metropolitan Opera Association.[15]

La Bohème. Una piccola storia sull'immortalità dell'amore e dell'amicizia by Carollina Fabinger is an illustrated version in Italian for young readers published by Nuages, Milano 2009, ISBN 9788886178891.

Modernizations

Baz Luhrmann produced the opera for Opera Australia in 1990[16] with modernized supertitle translations, and a budget of only A$60,000. A DVD was issued of the stage show. This version was set in 1957, rather than the original period of 1830.[16] The reason for updating La bohème to this period, according to Baz Luhrmann, was that "... [they] discovered that 1957 was a very, very accurate match for the social and economic realities of Paris in the 1840s."[16] In 2002, Luhrmann restaged his version on Broadway and won a Tony Award.[17] To play the eight performances per week on Broadway, three casts of Mimìs and Rodolfos, and two Musettas and Marcellos, were used in rotation.[18]

Rent, a 1996 musical by Jonathan Larson, is based on La bohème. Here the lovers, Roger and Mimi, are faced with AIDS and progress through the action with songs such as "Light My Candle", which have direct reference to La bohème.[19] Many of the character names are retained or are similar (e.g. the character Angel is given the surname "Schunard"), and at another point in the play, Roger's roommate and best friend Mark makes a wry reference to "Musetta's Waltz", which is a recurring theme throughout the first act and is played at the end of the second act.

References

- Notes

- ^ a b Groos, Arthur; Roger Parker (1986). Cambridge Opera Handbooks: La bohème. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0521264898.

- ^ a b Budden, Julian (2002). Puccini: His Life and Works. Oxford University Press. p. 494. ISBN 9780198164685.

- ^ "Opera Statistics". Operabase. http://operabase.com/top.cgi?lang=en#opera. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Julian Budden: "La bohème", Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed November 23, 2008), (subscription access)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i La bohème performance history at amadeusonline.net

- ^ a b The Manchester Guardian, 23 April 1897, p. 6

- ^ Eric Irvin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788–1914

- ^ The synopsis is based on The Opera Goer's Complete Guide by Leo Melitz, 1921 version.

- ^ Operadis, La bohème discography

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony, "Look What They're Doing to Opera", The New York Times, 22 December 2002

- ^ Details at Operadis

- ^ Shaman, William et al., More EJS: Discography of the Edward J. Smith recordings, Issue 81 of Discographies Series, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, pp. 455–456. ISBN 0313298351

- ^ Kalmanoff, Martin (1984). "The Missing Act". http://oq.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pdf_extract/2/3/121. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Ginell, Cary (2008). "Smart Licensing: Where Have I Heard That Before?". Music Reports Inc. https://www.musicreports.com/content_article.php?article_id=70. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- ^ Pritchett, V.S. (1983). La Bohème. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 0718123034.

- ^ a b c Maggie Shiels (10 July 2002). "Baz's Broadway opera". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/2305609.stm. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ 2002 production details at the IBDB database

- ^ Maggie Shiels (21 October 2002). "Baz's brilliant La bohème". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/reviews/2346351.stm. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ Anthony Tommasini (17 March 1996). "Theather; The Seven-Year Odyssey that Led to 'Rent'". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/17/theater/theather-the-seven-year-odyssey-that-led-to-rent.html. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- Annotations

External links

- La bohème: Free scores at the International Music Score Library Project.

- Upcoming performances from Operabase.com

- Recording of "Mi chimano Mimì" in German by Lotte Lehmann

- San Diego OperaTalk! with Nick Reveles: La bohème

- Libretto (in Italian) from OperaGlass

- (German) La Bohème opera

Laurence Olivier Award for Best New Opera Production (2001–2025) The Greek Passion – Royal Opera, London (2001) · Boulevard Solitude – Royal Opera, London (2002) · Wozzeck – Royal Opera, London (2003) · Les Troyens (Parts I and II) – English National Opera (2004) · Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District – Royal Opera, London (2005) · Madama Butterfly – English National Opera (2006) · Jenůfa – English National Opera (2007) · Pelléas et Mélisande – Royal Opera, London (2008) · Partenope - English National Opera (2009) · Tristan und Isolde - Royal Opera, London (2010) · Bohème - Soho Theatre (2011)

Complete list · (1993–2000) · (2001–2025) Categories:- Operas by Giacomo Puccini

- Italian-language operas

- 1896 operas

- Operas

- Operas set in France

- Paris in fiction

- Operas based on novels

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.