- Luther Bible

-

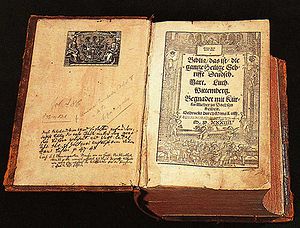

The Luther Bible is a German Bible translation by Martin Luther, first printed with both testaments in 1534. This translation became a force in shaping the Modern High German language. The project absorbed Luther's later years.[1] The new translation was very widely disseminated thanks to the printing press. [2]

Contents

Luther's work

While he was sequestered in the Wartburg Castle (1521–1522) Luther began to translate the New Testament into German in order to make it more accessible to all the people of the "Holy Roman Empire of the German nation." He used Erasmus' second edition (1519) of the Greek New Testament, known as the Textus Receptus. Luther didn’t use the Vulgate which is the official Latin translation used by the Catholic Church. Both Erasmus and Luther learned their first Greek at the Latin schools led by the Brethren of the Common Life (respectively in Deventer (Netherlands) and in Magdeburg). These lay brothers added late 15th century Greek as a new subject to their curriculum. Greek was seldom taught even at universities.

To help him in translating Luther would make forays into the nearby towns and markets to listen to people speak. He wanted to ensure their comprehension by a translation closest to their contemporary language usage. It was published in September 1522, six months after he had returned to Wittenberg. In the opinion of the 19th century theologian and church historian Philip Schaff,

"The richest fruit of Luther's leisure in the Wartburg, and the most important and useful work of his whole life, is the translation of the New Testament, by which he brought the teaching and example of Christ and the Apostles to the mind and heart of the Germans in life-like reproduction. It was a republication of the gospel. He made the Bible the people's book in church, school, and house." [3]

Part of a series on The Bible

Biblical canon

and booksOld Testament (OT)

New Testament (NT)

Hebrew Bible

Deuterocanon

Antilegomena

Chapters and verses

Development and

authorshipAuthorship

Jewish canon

Old Testament canon

New Testament canon

Mosaic authorship

Pauline epistles

Johannine works

Petrine epistlesTranslations and

manuscriptsSamaritan Torah

Dead Sea scrolls

Masoretic text

Targums · Peshitta

Septuagint · Vulgate

Gothic Bible · Vetus Latina

Luther Bible · English BiblesBiblical studies Dating the Bible

Biblical criticism

Historical criticism

Textual criticism

Canonical criticism

Novum Testamentum Graece

Documentary hypothesis

Synoptic problem

NT textual categories

Internal consistency

Archeology · Artifacts

Science and the BibleInterpretation Hermeneutics

Pesher · Midrash · Pardes

Allegorical interpretation

Literalism

ProphecyPerspectives Gnostic · Islamic · Qur'anic

Christianity and Judaism

Inerrancy · Infallibility

Criticism of the Bible Bible book

Bible book

Publication

The translation of the entire Bible into German was published in a six-part edition in 1534, a collaborative effort of Luther, Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Caspar Creuziger, Philipp Melanchthon, Matthäus Aurogallus, and Georg Rörer. Luther worked on refining the translation up to his death in 1546: he had worked on the edition that was printed that year.

There were 117 original woodcuts included in the 1534 edition issued by the Hans Lufft press in Wittenberg. They reflected the recent trend (since 1522) to include artwork to reinforce the textual message.[4]

Theology

Luther added the word "alone" (allein in German) to Romans 3:28 controversially so that it read: "thus, we hold, then, that man is justified without the works of the law to do, alone through faith"[5] The word "alone" does not appear in the original Greek text,[6] but Luther defended his translation by maintaining that the adverb "alone" was required both by idiomatic German and the apostle Paul's intended meaning.[7]

View of canonicity

Initially, Luther had a low view of the books of Esther, Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation. He called the Epistle of James "an epistle of straw," finding little in it that pointed to Christ and His saving work. He also had harsh words for the book of Revelation, saying that he could "in no way detect that the Holy Spirit produced it."[8] In his New Testament, Luther placed Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Revelation at the end and differentiated these from the other books which he considered "the true and certain chief books of the New Testament. The four which follow have from ancient times had a different reputation."[9] His views on some of these books changed in later years.

Luther chose to place the Apocrypha between the Old and New Testaments. These books and addenda to canonical books are found in the Greek Septuagint but not in the Hebrew Masoretic text. Luther left the translating of them largely to Philipp Melanchthon and Justus Jonas.[10] They were not listed in the table of contents of his 1532 Old Testament, and they were given the well-known title: "Apocrypha: These Books Are Not Held Equal to the Scriptures, but Are Useful and Good to Read" in the 1534 Bible.[11] See also Biblical canon, Development of the Christian Biblical canon, and Biblical Apocrypha.

Impact

The Luther Bible was not the first German translation, but it was by far the most influential.

The Luther Bible by reason of its widespread circulation facilitated the emergence of the modern German language by standardizing it for the peoples of the Holy Roman Empire, an empire extending throughout and well beyond present day Germany. It is considered a landmark in German literature, with Luther's vernacular style often praised by modern German sources for its forceful vigor ("kraftvolles Deutsch")[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20] that he chose to translate the Scripture.

Luther’s significance was largely due to his influence on the emergence of the German language and nationalism. This importance stemmed predominantly from his translation of the Bible into the vernacular, which was potentially as revolutionary as canon law and the burning of the papal bull.[21] Luther’s goal was to equip every Christian in Germany with the ability to hear the Word. Thus, by 1534 he completed his translation of the old and new testaments from Hebrew and Greek into the vernacular, one of the most significant acts of the Reformation.[22] Although Luther was not the first to attempt this translation, his was superior to all its predecessors. Previous translations contained poor German and were that of Vulgate, (translations of translations) rather than a direct translation to German text.[21] Luther sought to get as close to the original text as possible but at the same time, his translation was guided by how people spoke in the home, on the street and in the marketplace.[23] Luther combined his faithfulness to the language spoken by the common people to produce a work which the common man could relate to.[24] This aspect of Luther’s creation led German writers such as Goethe and Nietzsche to thoroughly praise Luther’s Bible.[25] The fact that the new Bible was printed in the vernacular allowed it to spread rapidly as it could be read by all. Hans Lufft, a renowned Bible printer in Wittenberg printed over one hundred thousand copies between 1534 and 1574 which went on to be read by millions.[26] Luther’s Bible was virtually present in every German Protestant’s home, and there can be no doubts regarding the vast biblical knowledge attained by the German common masses.[27] As a testament to the vast influence of Luther’s Bible, he even had large print Bibles made for those who had failing eyesight.[25] German humanist Johann Cochlaeus complained that

Luther's New Testament was so much multiplied and spread by printers that even tailors and shoemakers, yea, even women and ignorant persons who had accepted this new Lutheran gospel, and could read a little German, studied it with the greatest avidity as the fountain of all truth. Some committed it to memory, and carried it about in their bosom. In a few months such people deemed themselves so learned that they were not ashamed to dispute about faith and the gospel not only with Catholic laymen, but even with priests and monks and doctors of divinity."[28]

The spread of Luther's Bible had implications for the German language. The German language had been divided into many dialects, and different German statesmen could barely understand each other. This led Luther to conclude that “I have so far read no book or letter in which the German language is properly handled. Nobody seems to care sufficiently for it; and every preacher thinks he has a right to change it at pleasure and to invent new terms."[29] Scholars preferred to write in Latin. Luther popularized the Saxon dialect and adapted it to theology and religion, subsequently making it the common literary language used in books. He enriched the vocabulary with that of German poets and chroniclers.[29] For this accomplishment, a contemporary of Luther's, Erasmus Albertus, labeled him the German Cicero as he not only reformed religion, but the German language. Luther’s Bible has been hailed as the first German classic, comparable to the King James version of the Bible which became the first English classic. German Protestant writers and poets such as Klopstock, Herder and Lessing owe stylistic qualities to Luther’s Bible.[30] Ultimately, Luther adapted the words to fit the capacity of the German public and thus, due to the pervasiveness of his Bible, he created and spread the modern German language.[31]

Luther's Bible also had a role in the creation of German nationalism. Because it penetrated every Protestant home in Germany, his sayings and translation became part of the German national heritage.[32] Luther's program of Biblical exposure extended into every sphere of daily life and work, illuminating moral considerations to Germans. This exposure gradually became infused into the blood of the whole nation and occupied a permanent space in German history.[33] The popularity and influence of Luther’s translation gave him the confidence to act as a spokesperson of the nation and thus the leader of the anti-Roman movement in Germany.[34] In light of this, it also allowed him to become a prophet of the new German nationalism[35] and helped to determine the spirit of a new epoch in German history.[36]

In a sense, Luther’s Bible also empowered and liberated all Protestants who had access to it. Immediately, Luther’s translation was a public affirmation of reform and subsequently deprived the elite and priestly class of their exclusive control over words, as well as the word of God.[21] Through his translation, Luther strove to make it easier for the "simple people" to understand what he was teaching. In the major controversies amongst evangelicals at the time, most evangelicals did not understand the reasons for disagreement, let alone the commoners. Thus, Luther saw it as necessary to help those who were confused see that the disagreement between himself and the Catholic Church was real and had significance. His translation was made in order to allow the common man and woman to become aware of the issues at hand and develop an informed opinion.[37] The common individual was thus given the right to have a mind, spirit and opinion, who existed not as economic functionaries but as subjects to complex and conflicting aspirations and motives. In this sense, Luther’s Bible acted as a force towards the liberation of the German people. Luther’s social teachings and ideologies throughout the Bible undoubtedly had a role in the slow emancipation of European society from its long phase of clerical domination.[38] Luther gave men a new vision of the exaltation of the human self.[39] Luther’s Bible thus had broken the unchallenged domination of the Catholic Church, effectively splintering its unity. He had claimed the scriptures as the sole authority, and through his translation, every individual was able to abide by its authority, thus nullifying their need for a pope. As Bishop Fisher put it, Luther’s Bible had “stirred a mighty storm and tempest in the church” empowering the no longer clerically dominated public.[40]

Although not as significant as German linguistics, Luther’s Bible also had a large impression on educational reform throughout Germany. Luther’s goal of a readable and accurate translation of the Bible became a stimulus towards universal education. This stemmed from the notion that everyone should be able to read in order to understand the Bible.[21] Luther felt that man had fallen from grace and was ruled by his own selfishness, but ultimately had not lost his moral consciousness. In Luther's eyes all men were sinners and needed to be educated. Thus his Bible was a means of establishing a form of law, order and moral teachings which everyone could abide by as that they could all read and understand his Bible. This education subsequently allowed Luther to found a State Church and educate his followers into a law-abiding community.[41] Overall, the Protestant states of Germany were educational states which encouraged the spirit of teaching which was ultimately fueled by Luther’s Bible.

Finally, Luther’s Bible also had international significance in the spread of Protestantism. Luther’s translation influenced the English translations by William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale who in turn inspired many other translations of the Bible such as the Bishops' Bible of 1568, the Douay–Rheims Bible of 1582–1609, and the King James Version of 1611.[25] Luther’s work also inspired translations as far reaching as Scandinavia and the Netherlands. In a metaphor, it was Luther who broke the walls of translation and once such walls had fallen, the way was open to all, including some who were quite opposed to Luther’s belief.[42] Luther’s Bible spread its influence for the remolding of Western culture in all the great ferment of the sixteenth century. The worldwide implications of the translation far surpassed the expectations of even Luther himself.[43]

Memorable verses

Attributes that make Luther's translation of the Bible certainly characteristic are, on the one hand, a poetic, embellishing style, and on the other hand, his connection and closeness to the German people and their language.[citation needed]

These passages are exemplary: Verse Luther Bible English Translation (literal) English Meaning Notes Gen 2:23 "[...] Man wird sie Männin heißen, darum daß sie vom Manne genommen ist." "One will call her she-man, therefore that she was taken out of the man." "[...] She shall be called Woman, because she was taken out of Man." Here Luther tried to preserve the resemblance of Hebrew ish (man) and ishah (woman) by adding the female German suffix -in to the masculine word Mann, because the correct word (at that time), Weib, does not resemble it. (As neither does the modern Frau.) As like as adding she- to man in English, adding -in to Mann in German is to be considered grammatically awkward. Matthew 12:34 "[...] Wes das Herz voll ist, des geht der Mund über." "Of what the heart is full, of that the mouth overflows." "[...] For out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks." Luther used this as an example of how he would translate something for the people to understand it correctly. John 11:35 "Und Jesus gingen die Augen über." "And Jesus' eyes overflowed." "Jesus wept." Poetic. John 19:5 "[...] Sehet, welch ein Mensch!" "Behold what a man (this is)!" "[...] Behold the man!" Luther emphasizes Jesus' glory despite this ignoble situation, though it is to be considered an incorrect translation. See also: Ecce Homo. See also

References

Notes

- ^ Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: Shaping and Defining the Reformation, 1521-1532, Minneapolis: Fortress, p. 46

- ^ Mark U. Edwards, Jr., Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther (1994)

- ^ History of the Christian Church, 8 vols., (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 7:xxx.[1]

- ^ Carl C. Christensen, "Luther and the Woodcuts to the 1534 Bible," Lutheran Quarterly, Winter 2005, Vol. 19 Issue 4, pp 392-413

- ^ The 1522 "Testament" reads at Romans 3:28: "So halten wyrs nu, das der mensch gerechtfertiget werde, on zu thun der werck des gesetzs, alleyn durch den glawben" (emphasis added to the German word for "all." [2]

- ^ The Greek text reads: λογιζόμεθα γάρ δικαιоῦσθαι πίστει ἄνθρωπον χωρὶς ἔργων νόμου ("for we reckon a man to be justified by faith without deeds of law")[3]

- ^ Martin Luther, On Translating: An Open Letter (1530), Luther's Works, 55 vols., (St. Louis and Philadelphia: Concordia Publishing House and Fortress Press), 35:187–189, 195; cf. also Heinz Bluhm, Martin Luther Creative Translator, (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1965), 125–137.

- ^ Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Martin Luther. Q&A

- ^ http://www.bible-researcher.com/antilegomena.html

- ^ Martin Brecht, Martin Luther, James L. Schaaf, trans., 3 vols., (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1985-1993), 3:98.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Schreiber, Mathias (2006). Deutsch for sale, Der Spiegel, no. 40, October 2, 2006 ("So schuf er eine Hochsprache aus Volkssprache, sächsischem Kanzleideutsch (aus der Gegend von Meißen), Predigt und Alltagsrede, eine in sich widersprüchliche, aber bildhafte und kraftvolle Mischung, an der die deutschsprachige Literatur im Grunde bis heute Maß nimmt.")

- ^ Köppelmann, K. (2006) . Zwischen Barock und Romantik: Mendelssohns kirchliche Kompositionen für Chor ("Between Baroque and Romanticism: Mendelssohn's ecclesiastic choir compositions"), Mendelssohn-Programm 2006, p. 3 ("Martin Luthers kraftvolle deutsche Texte werden durch Mendelssohns Musik mit emotionalen Qualitäten versehen, die über die Zeit des Bachschen Vorbildes weit hinaus reicht und das persönlich empfindende romantische Selbst stark in den Vordergrund rückt.")

- ^ Werth, Jürgen. Die Lutherbibel ("The Luther Bible"), in Michaelsbote: Gemeindebrief der Evangelischen Michaeliskirchengemeinde ("St. Michael's Messenger: Parish newsletter of the Protestant Community of St. Michael's Church"), no. 2, May/June/July, 2007, p. 4. ("Gottes Worte für die Welt. Kaum einer hat diese Worte so kraftvoll in die deutsche Sprache übersetzt wie Martin Luther.")

- ^ Lehmann, Klaus-Dieter (2009). Rede von Klaus-Dieter Lehmann zur Ausstellungseröffnung von "die Sprache Deutsch" ("Speech held by Klaus-Dieter Lehmann upon the opening of the exposition 'The German language'"), Goethe-Institut ("Und so schuf der Reformator eine Sprache, indem er, wie er selbst sagt, 'dem Volk auf's Maul schaut', kraftvoll, bildhaft und Stil prägend wie kein anderes Dokument der deutschen Literatur.")

- ^ Weigelt, Silvia (2009). Das Griechlein und der Wagenlenker - Das kommende Jahr steht ganz im Zeichen Philip Melanchtons ("The Greek writer and the charioteer: 2010 to be the official Philipp Melanchthon year"), mitteldeutsche-kirchenzeitungen.de, online portal of the two print church magazines Der Sonntag and Glaube und Heimat ("Wenn auch die kraftvolle und bilderreiche Sprache des Bibeltextes zu Recht als Luthers Verdienst gilt, so kommt Melanchthon ein gewichtiger Anteil am richtigen sprachlichen Verständnis des griechischen Urtextes und an der sachlichen Genauigkeit der Übersetzung zu.")

- ^ Hulme, David (2004). Die Bibel - ein multilinguales Meisterwerk ("The Bible: A multi-lingual masterpiece"), visionjournal.de, no. 2, 2006, the German version of the spiritual magazine Vision: Insights and New Horizons published by Church of God, an International Community available in English at www.vision.org ("Luthers Bibelübersetzung mit ihrer kraftvollen, aus ostmitteldeutschen und ostoberdeutschen Elementen gebildeten Ausgleichssprache hatte auf die Entwicklung der neuhochdeutschen Sprache großen Einfluss.")

- ^ Salzmann, Betram; Schäfer, Rolf (2009). Bibelübersetzungen, christliche deutsche ("Bible translations, Christian and German"), www.wibilex.de: Das wissenschaftliche Bibellexikom im Internet ("die Orientierung an der mündlichen Volkssprache, die zu besonders kräftigen und bildhaften Formulierungen führt")

- ^ Schmitsdorf, Joachim (2007). Deutsche Bibelübersetzungen: Ein Überblick ("German Bible translations: An overview") ("Kraftvolle, melodische Sprache, die gut zum Auswendiglernen geeignet, aber auch oft schwer verständlich und altertümelnd ist")

- ^ Lutherdeutsch ("Luther's German") ("Luther’s Sprache ist saft- und kraftvoll.")

- ^ a b c d Carter Lindberg, The European Reformation (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1996), 91

- ^ A.G. Dickens, The German Nation and Martin Luther (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1974), 206

- ^ ibid, 91

- ^ Mark Antliff, The Legacy of Martin Luther (Ottawa, McGill University Press, 1983), 11

- ^ a b c Carter Lindberg, The European Reformation (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1996), 92

- ^ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 5

- ^ A.G. Dickens, The German Nation and Martin Luther (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1974), 134

- ^ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 6

- ^ a b Ibid, 12

- ^ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 13

- ^ Ibid, 13

- ^ Gerhard Ritter , Luther: His life and Work ( New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1963), 216

- ^ Idib, 216

- ^ Hartmann Grisar, Luther: Volume I (London: Luigi Cappadelta, 1914), 402

- ^ V.H.H Green. Luther and the Reformation (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1964), 193

- ^ Gerhard Ritter , Luther: His life and Work ( New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1963), 213

- ^ Mark Edwards, Luther and the False Brethren (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1975), 193

- ^ A.G. Dickens, The German Nation and Martin Luther (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1974), 226

- ^ Gerhard Ritter , Luther: His life and Work ( New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1963), 210

- ^ V.H.H Green. Luther and the Reformation (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1964), 10

- ^ Gerhard Ritter , Luther: His life and Work ( New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1963), 241

- ^ B.A. Gerrish, Reformers in Profile (Philadelphia: Fortpress Press, 1967), 112

- ^ Gerhard Ritter , Luther: His life and Work ( New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1963), 212

Additional reading

- Antliff, Mark. The Legacy of Martin Luther. Ottawa, McGill University Press, 1983

- Atkinson, James. Martin Luther and the Birth of Protestantism. Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1968

- Bindseil, H.E. and Niemeyer, H.A. Dr. Martin Luther's Bibelübersetzung nach der letzten Original-Ausgabe, kritisch bearbeitet. 7 vols. Halle, 1845–55. [The N. T. in vols. 6 and 7. A critical reprint of the last edition of Luther (1545). Niemeyer died after the publication of the first volume. Comp. the Probebibel (the revised Luther-Version), Halle, 1883. Luther's Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen und Fürbitte der Heiligen (with a letter to Wenceslaus Link, Sept. 12, 1530), in Walch, XXI. 310 sqq., and the Erl. Frkf. ed., vol. LXV. 102–123.]

- Bluhm, Heinz. Martin Luther: Creative Translator. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1965.

- Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. 3 Volumes. James L. Schaaf, trans. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–1993. ISBN 0-8006-2813-6, ISBN 0-8006-2814-4, ISBN 0-8006-2815-2.

- Dickens, A.G. The German Nation and Martin Luther. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1974

- Edwards, Mark Luther and the False Brethren Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1975

- Gerrish, B.A. Reformers in Profile. Philadelphia: Fortpress Press, 1967

- Green, V.H.H. Luther and the Reformation. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1964

- Grisar, Hartmann. Luther: Volume I. London: Luigi Cappadelta, 1914

- Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformation. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1996

- Reu, [John] M[ichael]. Luther and the Scriptures. Columbus, Ohio: The Wartburg Press, 1944. [Reprint: St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1980].

- Reu, [John] M[ichael]. Luther's German Bible: An Historical Presentation Together with a Collection of Sources. Columbus, Ohio: The Lutheran Book Concern, 1934. [Reprint: St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1984].

- Ritter, Gerhard. Luther: His life and Work. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1963

External links

- German Biblia 1545 Edition PDF's

- Luther's Biblia Germanica 1545 Last Hand Edition

- Luther's Translation of the Bible in Philip Schaff's History of the Christian Church

Martin Luther Works A Mighty Fortress Is Our God · On War against the Turk · Large Catechism · Luther Bible · On the Bondage of the Will · On the Freedom of a Christian · On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church · Small Catechism · The Adoration of the Sacrament · The Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ—Against the Fanatics · Theology of the Cross · The Ninety-Five Theses · To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation · Confession Concerning Christ's Supper · On Secular Authority · Formula missae · Deutsche Messe · Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants · Smalcald Articles · On the Jews and Their Lies · Vom Schem Hamphoras · On the Councils and the Church

Topics People Categories:- 1534 books

- Early printed Bibles

- Martin Luther

- Protestant Reformation

- German Bible translations

- Christian terms

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.