- University of Oslo

-

University of Oslo Universitetet i Oslo

Latin: Universitas Osloensis Established 1811 Type Public university Rector Ole Petter Ottersen (2009-) Academic staff 3212 (2010) Admin. staff 2598 (2010) Students 27628 (2010) Location Oslo, Norway Affiliations EUA Website www.uio.no The University of Oslo (Norwegian: Universitetet i Oslo), is the oldest and largest university in Norway, situated in the Norwegian capital of Oslo. The university was founded in 1811 as The Royal Frederick University (in Norwegian Det Kongelige Frederiks Universitet and in Latin Universitas Regia Fredericiana) and was modelled after the recently established University of Berlin. It was originally named after King Frederick of Denmark and Norway and received its current name in 1939.

The university has faculties of Law, Medicine, Humanities, Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Dentistry, Social Sciences, Education and (Lutheran) Theology. The Faculty of Law is still located at the old campus on Karl Johans gate, near the National Theatre, the Royal Palace, and the Parliament, while most of the other faculties are located at a modern campus area called Blindern, erected from the 1930s. The Faculty of Medicine is split between several university hospitals in the Oslo area.

Currently the university has about 27,700 students and employs about 6,000 people. The university has consistently been ranked among the world's top 100 universities by the Academic Ranking of World Universities; in 2010 it was ranked as the best in Norway, 24th best in Europe and 75th best in the world.[1] The 2011 QS World University Rankings ranked the university 108th in the world.[2] After the dissolution of the Dano-Norwegian union in 1814, close academic ties between the countries have been maintained.[citation needed] The University of Oslo was the only university in Norway until 1946, and hence informally often known as simply "universitetet" ("the university").[citation needed] It was also informally referred to as "The Royal Frederick's" (Det Kgl. Frederiks) for short.

The University of Oslo is home to five Nobel Prize winners. One of the Nobel Prizes, the Nobel Peace Prize, was awarded in the university's atrium until 1989.[citation needed]

Units

King Frederick of Denmark and Norway was the founder of the university

King Frederick of Denmark and Norway was the founder of the university

Faculty of Theology

The Faculty of Theology conducts research and teaching within Theology, Christian Studies, Inter-religious Studies and Diaconal Studies.

Faculty of Law

- Centre for European Law

- Department of Criminology and the Sociology of Law

- Department of Private Law

- Norwegian Research Center for Computers and Law (NRCCL)

- Department of Public and International Law

- Norwegian Centre for Human Rights

- Scandinavian Institute of Maritime Law

The Faculty of Law. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in this building until 1989.

Central campus of the university, where today only the faculty of law is located. These buildings were inspired by the famous buildings of Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin.

Central campus of the university, where today only the faculty of law is located. These buildings were inspired by the famous buildings of Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin.

Faculty of Medicine

- Institute of Health and Society

- Institute of Basic Medical Sciences

- Institute of Clinical Medicine

- Institute of Forensic Medicine

- Faculty Division Oslo University Hospital

Centres of Excellence:

- Centre for Molecular Biology and Neuroscience

- Centre for Immune Regulation

- Centre for Cancer Biomedicine

Faculty of Humanities

- Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History

- Department of Cultural Studies and Oriental Languages

- Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas

- Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages

- Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies

- Department of Media and Communication

- Department of Musicology

- Centre for Ibsen Studies

- Centre for the Study of Mind in Nature

- The Norwegian University Centre in St. Petersburg

- The Norwegian Institute in Rome

- Centre for French-Norwegian research cooperation within the social sciences and the humanities

Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences

- Department of Biology

- Department of Chemistry

- Department of Geosciences

- Department of Informatics

- Department of Mathematics

- Department of Molecular Biosciences

- Department of Physics

- Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics

- School of Pharmacy

- Centre for Entrepreneurship

- Centre for Material sciences and Nanotechnology (SMN)

- Centre for Physics of Geological Processes (PGP)

- Centre of Mathematics for Applications (CMA)

- Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES)

- Centre for Theoretical and Computational Chemistry (CTCC)

- Centre for Innovative Natural Gass Processes and Products (inGAP)

- Centre for Accelerator Based Research and Energy Physics (SAFE)

Faculty of Dentistry

- Department of Oral Biology* Institute of Clinical Dentistry

Faculty of Social Sciences

- Department of Sociology and Human Geography

- Department of Political Science

- Department of Psychology

- Department of Social Anthropology

- Department of Economics

- Centre for technology, innovation and culture

- ARENA - Centre for European Studies

- Centre of Equality, Social Organization, and Performance (ESOP)

Faculty of Education

- Department of Teacher Education and School Research

- Department of Special Needs Education

- Department for Educational Research

- InterMedia

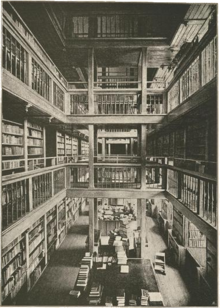

University Library

Main article: University Library of Oslo- Library of Medicine and Health Sciences

- Library of Humanities and Social Sciences

- Faculty of Law Library

- Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Library

Units directly under The Senate

- Centre for Gender Research

- Centre for Development and The Environment

- The Biotechnology Centre of Oslo

- Molecular Life Science

- International Summer School

Museums

Museum of Cultural History

- The Historical Museum

- Collection of Coins and Medals

- Ethnographic Museum

- The Viking Ship Museum

Natural History Museum

- Natural History Museum at the University of Oslo

- Mineralogical-geological Museum

- Paleontological Museum

- Zoological Museum

- Botanical Garden

- Botanical Museum

History

Founding

In 1811, the decision was taken to establish the first university in the Dano-Norwegian Union, after a successful campaign which resulted in King Fredrik VI's agreeing to the establishment of what he had earlier believed might prove an institution encouraging of political-separatist tendencies. In 1813, The Royal Fredrik's University was founded in Christiania; Christiania was, at the time, a small, provincial town in a country without a capital city. Only a year later, however, circumstances changed dramatically. Norway proclaimed its independence and adopted its own constitution. Independence was somewhat restricted when Norway was obliged to enter into a legislative union with Sweden as the result of the outcome of the War of 1814; Norway retained its own constitution and independent state institutions, while royal power and foreign affairs were shared with Sweden. At a time when Norwegians feared political domination by the Swedes, the new university became a key institution that contributed to Norwegian political and cultural independence.

Educated civil servants

The main function of The Royal Fredrik’s University was to educate a new class of civil servants. Although Norway was in a legislative union with Sweden, it was a sovereign state–– and needed educated people to run it. Civil servants were needed, as well as parliamentary representatives and ministers. The university also became the centre for a survey of the country – a survey of national culture, language, history and folk traditions. The staff of the university strove to undertake a wide range of practical tasks necessary for developing the infrastructure critical to a modern society. When the union with Sweden was dissolved in 1905, the university became important for producing highly educated men and women who could serve as experts in a society which placed increasing emphasis on ensuring that all its citizens enjoy a life of dignity and security. Education, health services and public administration were among those fields that recruited personnel from among the university’s graduates. The university remained Norway’s only institution of higher education until 1946. In 1939, the name was changed to The University of Oslo.

A university active in public affairs

Norway’s only university was intended to serve not just the state, but society at large, through the education of a technical and mercantile elite as well as civil servants and clergymen. At the founding of the university, it was stipulated that it should be a university for the people, not a “royal” university. It was thought that the university should contribute to the development of the nation; the university could accomplish this by focusing on more practical forms of academic training.

Research and teaching

Throughout the 1800s, the university’s academic disciplines became more specialised. Gradually, professors became researchers who lectured, rather than the opposite, i.e. they became lecturers who also authored books. Over the years, the primary goals of the university have remained more or less unchanged. By providing higher education in a variety of specialised disciplines, the university has become a universitas, i.e. part of an international network of research-intensive academic institutions. The university has been expected to foster and guarantee basic educational standards and ideals and encourage the dissemination of these standards and ideals throughout society. Finally, the university has been expected to expand our basic knowledge by conducting basic research.

Both a university for public enlightenment and a university of excellence

If we examine viewpoints dating from the time of the celebration of the university's centennial in 1911, regarding peoples’ hopes and expectations for the university, two basic concepts emerge. The university should be an institution for public enlightenment – and a university of academic excellence. These two concepts do not necessarily conflict with each other.

More professional management

One of the major changes in the university came during the 1870s when a greater emphasis became placed upon research. The management of the university became more professional, academic subjects were reformed and the forms of teaching evolved. Disciplines became more specialized and “classical” education came under increasing pressure.

New academic ideals

Research changed qualitatively around the turn of the century, i.e. new methods, scientific theories and forms of practice changed the nature of research. It was decided that teachers should arrive at their posts as highly-qualified academics and continue their academic researcher alongside their role as teachers. Scientific research – whether to launch or test out new theories, to innovate or to pave the way for discoveries across a wide range of disciplines – became part of the increased expectations placed on the university. Developments in society created a need for more and more specialised and practical knowledge, not merely competence in theology or law, for example. The university strove to meet these expectations through increasing academic specialisation.

The first rector

The position of rector was established by Parliament in 1905 following the Dissolution of the Union. Waldemar Christofer Brøgger was Professor of Geology and became the university's first rector. In his acceptance speech, Brøgger offered a new and original perspective on the occasion of the university's centennial jubilee. To Brøgger, the university was first and foremost,an international institution existing in the context of a larger family of universities. Brøgger believed it was scientific and knowledge-based innovation which would help distinguish Norway internationally and make her the peer of other nations.

Funding for research

Brøgger vacillated between a certain pessimism and a powerfully energetic attitude regarding how to procure finances for research and fulfil his more general funding objectives. With the establishment of the national research council after World War II, Brøgger's vision was largely fulfilled; research received funding independent of teaching. This coincided with a massive rise in student enrolment during the 1960s, which again made it difficult to balance research with the demands for teaching. In the years leading up to 1940, research was more strongly linked with the growth of the nation, with progress and self-assertion; research was also seen to contribute to Norway’s commitment to international academic and cultural development.

Increased recognition for research accomplishments

During the period between World War I and World War II, research among Norwegian researchers resulted in two Nobel prizes. The Nobel prize in Social Economics was awarded to Ragnar Frisch. The Nobel prize in Chemistry was awarded to Odd Hassel. In the field of linguistics, several Norwegian researchers distinguished themselves internationally. Increased research activity during the first half of the 1900s was part of an international development that also included Norway. Student enrolment doubled between 1911 and 1940, and students were recruited from increasingly broad geographical, gender and social bases. The working class was still largely left behind, however.

The university during the war

During the German occupation, which lasted from 1940-1945, the university’s rector, Didrik Arup Seip, was imprisoned, and the university was placed under the management of a rector appointed by the Norwegian Nazi Party, NS. NS Adolf Hoel. A number of students participated in the Norwegian resistance movement; after a fire was set in the university auditorium, Reich Commissar Terboven ordered the university closed and the students arrested. A number of students and teachers were detained by the Germans nearly until the end of the war.

Optimism regarding knowledge

The university emerged from the years of German occupation with strengthened esteem. There was considerable anticipation about what education could do to spur growth and prosperity in the newly liberated Norway. Students were integrated into the welfare state. Public authorities made loans available to students whose families were unable to provide financial assistance the State Educational Loan Fund for Young Students was established in 1947. As a result, the post-war years saw a record increase in student numbers. Many of these students had been unable to begin their studies or had seen their studies interrupted because of the war; they could now enrol. For the 1945 autumn semester, 5951 students registered at the university. This represented the highest student enrolment at UiO up to that time. In 1947, the number had risen to more than 6000 students. This reprecented a 50 per cent increase in the number of students compared to the number enrolled prior to the war.

Explosion in student numbers

In no previous period had a single decade brought so many changes for the university as the 1960s. The decade represented an unparalleled period of growth. From 1960 to 1970, student enrolment tripled, rising from 5,600 to 16,800. This tremendous influx would have been enough in itself to transform the way the university was perceived, from both the inside and the outside. As it turned out, the changes were even more comprehensive. The university campus at Blindern was expanded, and the number of academic and administrative employees rose. The number of academic positions doubled, from fewer than 500 to around 1,200. The increase in the number of students and staff transformed traditional forms of work and organisation. The expansion of the Blindern complex allowed the accommodation of 7,000 students. The explosive rise in student numbers during the 1960s impacted the Blindern campus in particular. The faculties situated in central Oslo – Law and Medicine – experienced only a doubling in student enrolment during the 1960s, while the number of students in the humanities and social sciences tripled.

Student uprising

By 1968, revolutionary political ideas had taken root in earnest among university students. "The student uprising" became a turning point in the history of universities throughout the western world. Often, the outlook for students in the 1960s was bleak. More than ever before came from non-academic backgrounds and had few role models. The “University of the Masses” was unable to lift all its students to the “lofty, elite positions” enjoyed by previous generations of academics. Many students dissociated themselves, therefore, from the so-called “establishment” and the way the establishment functioned. Many were impatient and wanted to use their knowledge to change society. It was thought that academics should stand in solidarity with the underprivileged.

More female students

The most fundamental change in the student population was the increasing proportion of women students. Throughout the 1970s, the number of women increased until it made up the majority of students. At the same time, the university became a centre for the organised women's liberation movement, which emerged in the 1970s.

Multiple increase in student numbers

Up until the millennium, the number of students enrolled at the university rose exponentially. In 1992, UiO implemented a restriction on admissions for all of its faculties for the first time. A large part of the explanation for the high student numbers was thought to be found in the poor job market. In 1996, there were 38,265 students enrolled at UiO. This level was approximately 75 per cent above the average during the 1970s and 1980s. The strong rise in student numbers during the 1990s was attributed partially to the poor labour market. The Ministry of Education and Research recently concluded that, from a socio-economic perspective, investments made in education during the 1990s have proven to be extremely profitable.

Rectors

Main article: List of rectors for the University of OsloNotable Alumni

- Odd Arne Westad - Professor of international history at London School of Economics.

- Jens Stoltenberg - Prime minister of Norway.

- Gro Harlem Brundtland - Former prime minister of Norway.

- Petrit Selimi - Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Kosovo

Nobel laureates

Five researchers at the University of Oslo have been awarded Nobel Prizes:

- Fridtjof Nansen - 1922 - Peace (Although it was not Nansen's scientific work that earned him the prize.)

- Ragnar Frisch - 1969 - Economics

- Odd Hassel - 1969 - Chemistry

- Ivar Giæver - 1973 - Physics

- Trygve Haavelmo - 1989 - Economics

Seal

The seal of the University of Oslo features Apollo with the Lyre, and dates from 1835. The seal has been redesigned several times, most recently in 2009.

Studies

The University of Oslo welcomes qualified international students from around the world to apply for the programmes. Admission for international applicants.

Student life

Like all public institutions of higher education in Norway, the university does not charge tuition fees. However, a small fee of NOK 510 (roughly US$70) per term goes to the student welfare organisation Foundation for Student Life in Oslo, to subsidise kindergartens, health services, housing and cultural initiatives, the weekly newspaper Universitas and the radio station Radio Nova.

In addition a the students are charged a copy and paper fee of NOK 100[4] (roughly US$17) for full-time students and NOK 50 (roughly US$8.50) for part-time students. Lastly a voluntary sum of NOK 30 (roughly US$5) is donated to SAIH (Studentenes og Akademikernes Internasjonale Hjelpefond).

Rankings

The Shanghai Jiao Tong University's Academic Ranking of World Universities ranked UiO 75th worldwide (and best in Norway),[5] while The Times Higher Education World University Rankings ranked UiO 186th worldwide in 2010 (2nd in Norway behind the University of Bergen).[6]

Also in 2010, the QS World University Rankings[7] ranked UiO 100th worldwide, while the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities ranked UiO 53rd worldwide.[8]

See also

- Higher education in Norway

- List of modern universities in Europe (1801–1945)

References

- ^ http://www.arwu.org/ARWU2010.jsp

- ^ http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2011?page=2

- ^ Based on John Peter Collett: "Historien om Universitetet i Oslo", Universitetsforlaget 1999, Jorunn Sem Fure: "Forskningsuniversitetet - retorisk ideal eller realitet?" in John Peter Collett, Jan Eivind Myhre and Jon Skeie (ed): "Kunnskapens betingelser. Vidarforlaget 2009 and Kunnskapsdepartementet, Desember 2010: "Tilbud og etterspørsel etter høyere utdannet arbeidskraft fram mot 2020".

- ^ "Kopiavgiften" (in Norwegian). University of Oslo. 2010-09-03. http://www.uio.no/studier/admin/semesteravgift/kopiavgift.html. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ "Top 500 World Universities". Shanghai Jiao Tong University. http://www.arwu.org/ARWU2010.jsp. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ^ http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/2010-2011/top-200.html

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2010 Results". http://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2010/results.

- ^ http://www.webometrics.info/top12000.asp?offset=50

External links

- The University of Oslo website

- The Foundation for Student Life in Oslo (Studentsamskipnaden)

- Universitas (student newspaper)

- Radio Nova (student radio)

Institutional Network of the Universities from the Capitals of Europe (UNICA) Amsterdam (UvA) · Athens · Belgrade · Berlin (FUB) · Berlin (HUB) · Bratislava · Brussels (VUB) · Brussels (ULB) · Bucharest · Budapest · Copenhagen · Dublin (UCD) · Helsinki · Lausanne · Lisboa · Ljubljana · London (UCL) · Madrid (UAM) · Madrid (UCM) · Moscow · Nicosia · Oslo · Paris I · Paris III · Paris VI · Paris-Dauphine · Prague · Riga · Rome-La Sapienza · Rome-Tor Vergata · Rome-Tre · Skopje · Sofia · Stockholm · Tallinn (TU) · Tallinn (TUT) · Tirana · Vienna · Vilnius · Warsaw · Zagreb

Universities and colleges in Norway Universities Agder · Bergen · Life Sciences · Nordland · Oslo · Science and Technology · Stavanger · University of TromsøSpecialised universities University colleges Akershus · Bergen · Buskerud · Finnmark · Gjøvik · Harstad · Hedmark · KHiB · KHiO · Lillehammer · Narvik · Nesna · Nord-Trøndelag · Oslo · Police · Sámi · Sogn og Fjordane · Stord/Haugesund · Sør-Trøndelag · Telemark · Tromsø · Vestfold · Volda · Østfold · ÅlesundPrivate colleges Coordinates: 59°56′23.77″N 10°43′19.43″E / 59.9399361°N 10.7220639°E

Categories:- University of Oslo

- Educational institutions established in 1811

- 1811 establishments in Norway

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.