- Berlin Conference (1884)

-

"Berlin Conference" redirects here. For other uses, see Berlin Conference (disambiguation).

The Berlin Conference (German: Kongokonferenz or "Congo Conference") of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence as an imperial power. Called for by Portugal and organized by Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of Germany, its outcome, the General Act of the Berlin Conference, is often seen as the formalisation of the Scramble for Africa. The conference ushered in a period of heightened colonial activity on the part of the European powers, while simultaneously eliminating most existing forms of African autonomy and self-governance.

Contents

Early history of the conference

In the early 1880s, European interest in Africa increased dramatically, due to Africa's abundance of valuable resources such as gold, timber, land, markets and labour power. Henry Morton Stanley's charting of the Congo River Basin (1874–1877) removed the last bit of terra incognita from European maps of the continent. In 1878, King Léopold II of Belgium, who had previously founded the International African Society in 1876, invited Stanley to join him. The International African Society had the goal of researching and 'civilizing' the continent. In 1878, the International Congo Society was also formed, having more economic goals, but still closely related to the former society. Léopold secretly bought off the foreign investors in the Congo Society, which was turned to imperialistic goals, with the African Society serving primarily as a philanthropic front.

From 1879 to 1885, Stanley returned to the Congo, this time not as a reporter, but as an envoy from Léopold with the secret mission to organize a Congo state, which would become known as the Congo Free State. At the same time, the French marine officer Pierre de Brazza traveled into the western Congo basin and raised the French flag over the newly-founded Brazzaville in 1881, in what is currently the Republic of Congo. Portugal, which also claimed the area due to old treaties with the Kongo Empire, made a treaty with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 26 February 1884 to block off the Congo Society's access to the Atlantic.

At the same time, other European countries gained colonial footholds in Africa. France occupied Tunisia and today's Republic of the Congo in 1881 — which partly convinced Italy to become part of the Triple Alliance — and also Guinea in 1884. In 1882, the United Kingdom occupied nominally Ottoman Egypt, which in turn ruled over the Sudan and what would later become British Somaliland.

Conference

King Leopold II was able to convince France and Germany that common trade in Africa was in the best interests of all three countries. On the initiative of Portugal, Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor, called on representatives of Austria–Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden-Norway (union until 1905), the Ottoman Empire, and the United States to take part in the Berlin Conference to work out policy. However, the United States did not actually participate in the conference.

General Act

The General Act fixed the following points:

- The Free State of the Congo was confirmed as private property of the Congo Society. Thus the territory of today's Democratic Republic of the Congo, some two million square kilometers, was made essentially the property of Léopold II (because of the terror regime established, it would eventually become a Belgian colony). It was primarily because of this point that Joseph Conrad sarcastically referred to the conference as "the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs" in his novella Heart of Darkness.[1]

- The 14 signatory powers would have free trade throughout the Congo basin as well as Lake Niassa and east of this in an area south of 5° N.

- The Niger and Congo Rivers were made free for ship traffic.

- An international prohibition of the slave trade was signed.

- A Principle of Effectivity (see below) was introduced to stop powers setting up colonies in name only.

- Any fresh act of taking possession of any portion of the African coast would have to be notified by the power taking possession, or assuming a protectorate, to the other signatory powers.

- Which regions each European power had an exclusive right to 'pursue' the legal ownership of land (legal in the eyes of the other European powers).[2]:44

The first reference in an international act to the obligations attaching to "spheres of influence" is contained in the Berlin Act.

David Olusoga's Views

To counter the argument that Africa's modern day borders were strategically planned and dictated to the benefit of European powers, Olusoga and Erichsen states the following:

It is a common misconception that the Berlin Conference simply 'divvied up' the African continent between the European powers. In fact, all the foreign ministers who assembled in Bismarck's Berlin villa had agreed was in which regions of Africa each European power had the right to 'pursue' the legal ownership of land, free from interference by any other. The land itself remained the legal property of Africans.[2]:44

Principle of Effectivity

The Principle of Effectivity stated that powers could hold colonies only if they actually possessed them: in other words, if they had treaties with local leaders, if they flew their flag there, and if they established an administration in the territory to govern it with a police force to keep order (see Uti Possidetis). The colonial power also had to make use of the colony economically. If the colonial power did not do these things, another power could do so and take over the territory. It therefore became important to get leaders to sign a protectorate treaty and to have a presence sufficient to police the area.

Agenda

- Portugal - Britain The Portuguese government presented a project, known as the "Pink Map" (also called the "Rose-Colored Map"), in which the colonies of Angola and Mozambique were united by co-option of the intervening territory (land that later became Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi.) All of the countries attending the conference, except for the United Kingdom, endorsed Portugal's ambitions. A little more than five years later, in 1890, the British government, in breach of the Treaty of Windsor (and of the Treaty of Berlin itself[citation needed]), issued an ultimatum demanding that the Portuguese withdraw from the disputed area.

- France - Britain A line running from Say in Niger to Baroua, on the north-east coast of Lake Chad determined what part belonged to whom. France would own territory to the north of this line, and the United Kingdom would own territory to the south of it. The Nile Basin would be British, with the French taking the basin of Lake Chad. Furthermore, between the 11th and 15th degrees latitude, the border would pass between Ouaddaï, which would be French, and Darfur in Sudan, to be British. In reality, a no man's land 200 kilometres wide was put in place between the 21st and 23rd meridians.

- France - Germany The area to the north of a line formed by the intersection of the 14th meridian and Miltou was designated French, that to the south being German.

- Britain - Germany The separation came in the form of a line passing through Yola, on the Benoué, Dikoa, going up to the extremity of Lake Chad.

- France - Italy Italy was to own what lies north of a line from the intersection of the Tropic of Cancer and the 17th meridian to the intersection of the 15th parallel and 21st meridian.

Consequences

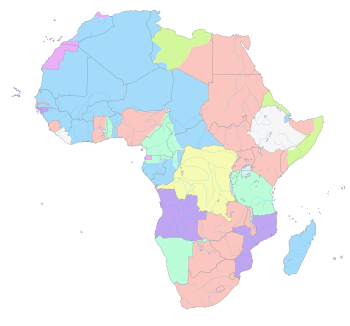

-

- The Berlin Conference was Africa's undoing in more ways than one. The colonial powers superimposed their domains on the African continent. By the time independence returned to Africa in 1950, the realm had acquired a legacy of political fragmentation that could neither be eliminated nor made to operate satisfactorily.[3]

The Scramble for Africa sped up after the Conference, since even within areas designated as their sphere of influence, the European powers still had to take possession under the Principle of Effectivity. In central Africa in particular, expeditions were dispatched to coerce traditional rulers into signing treaties, using force if necessary, as for example in the case of Msiri, King of Katanga, in 1891.

Within a few years, Africa was at least nominally divided up south of the Sahara. By 1895, the only independent states were:

- Liberia, founded with the support of the USA for returned slaves;

- Abyssinia (Ethiopia), the only free native state, which fended off Italian invasion from Eritrea in what is known as the First Italo-Abyssinian War of 1889-1896.

The following states lost their independence to the British Empire roughly a decade after (see below for more information):

- Orange Free State, a Boer republic founded by Dutch settlers;

- South African Republic (Transvaal), also a Boer republic;

By 1902, 90% of all the land that makes up Africa was under European control. The large part of the Sahara was French, while after the quelling of the Mahdi rebellion and the ending of the Fashoda crisis, the Sudan remained firmly under joint British–Egyptian rulership with Egypt being under British occupation before becoming a British protectorate in 1914.

The Boer republics were conquered by the United Kingdom in the Boer war from 1899 to 1902. Morocco was divided between the French and Spanish in 1911, and Libya was conquered by Italy in 1912. The official British annexation of Egypt in 1914 ended the colonial division of Africa.

By this point, all of Africa, with the exception of Liberia and Ethiopia, was under European rule.

References

- ^ "Historical Context: Heart of Darkness." EXPLORING Novels, Online Edition. Gale, 2003. Discovering Collection. Subscription required

- ^ a b Olusoga, David; Erichsen, Casper W. (2010). The Kaisers's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. London, UK: Faber and Faber. pp. 394. ISBN 978-0-571-23141-6.

- ^ de Blij, H.J.; Muller, Peter O. (1997). Geography: Realms, Regions, and Concepts.. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. pp. 340.

Bibliography

- Chamberlain, Muriel E. (1999). The Scramble for Africa. London: Longman, 1974, 2nd ed. ISBN 0582368812.

- Crowe, Sybil E. (1942). The Berlin West African Conference, 1884–1985. New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 0837132878 (1981, New ed. edition).

- Förster, Stig, Wolfgang J. Mommsen, and Ronald Edward Robinson (1989). Bismarck, Europe, and Africa: The Berlin Africa Conference 1884–1885 and the Onset of Partition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199205000.

- Hochschild, Adam (1999). King Leopold's Ghost. ISBN 0-395-75924-2.

- Petringa, Maria (2006). Brazza, A Life for Africa. ISBN 9781-4259-11980.

External links

Categories:- Colonialism

- History of Morocco

- Treaties of Denmark

- Treaties of the Ottoman Empire

- Treaties of the United Kingdom

- Treaties of the United States

- European colonisation in Africa

- 1884 in France

- 1885 in France

- 1884 in Germany

- 1885 in Germany

- 1884 in Portugal

- 1885 in Portugal

- Treaties of Austria-Hungary

- Diplomatic conferences in Germany

- 19th-century diplomatic conferences

- 1884 treaties

- 1884 in international relations

- 1885 in international relations

- Treaties of the Russian Empire

- Treaties of the German Empire

- Treaties of the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway

- Treaties of the French Third Republic

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Portugal

- Treaties of the Spanish Empire

- Treaties of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.