- Plasticity (physics)

-

"Plastic material" redirects here. For the material used in manufacturing, see Plastic.

Continuum mechanics  LawsSolids

LawsSolids

Stress · Deformation

Compatibility

Finite strain · Infinitesimal strain

Elasticity (linear) · Plasticity

Bending · Hooke's law

Failure theory

Fracture mechanics

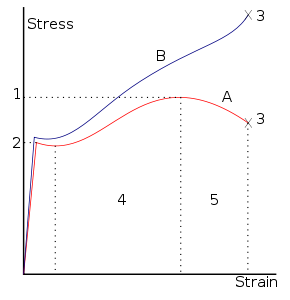

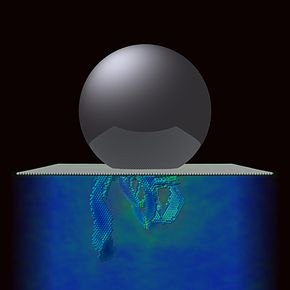

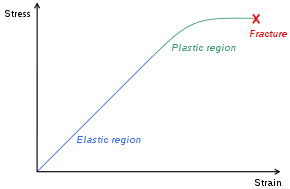

Frictionless/Frictional Contact mechanicsScientists A stress–strain curve typical of structural steel

A stress–strain curve typical of structural steel

1. Ultimate Strength

2. Yield Strength

3. Rupture

4. Strain hardening region

5. Necking region.

A: Apparent stress (F/A0)

B: Actual stress (F/A)In physics and materials science, plasticity describes the deformation of a material undergoing non-reversible changes of shape in response to applied forces.[1] For example, a solid piece of metal being bent or pounded into a new shape displays plasticity as permanent changes occur within the material itself. In engineering, the transition from elastic behavior to plastic behavior is called yield.

Plastic deformation is observed in most materials including metals, soils, rocks, concrete, foams, bone and skin.[2][3][4][5][6][7] However, the physical mechanisms that cause plastic deformation can vary widely. At the crystal scale, plasticity in metals is usually a consequence of dislocations. In most crystalline materials such defects are relatively rare. But there are also materials where defects are numerous and are part of the very crystal structure, in such cases plastic crystallinity can result. In brittle materials such as rock, concrete, and bone, plasticity is caused predominantly by slip at microcracks.

For many ductile metals, tensile loading applied to a sample will cause it to behave in an elastic manner. Each increment of load is accompanied by a proportional increment in extension, and when the load is removed, the piece returns exactly to its original size. However, once the load exceeds some threshold (the yield strength), the extension increases more rapidly than in the elastic region, and when the load is removed, some amount of the extension remains.

However, elastic deformation is an approximation and its quality depends on the considered time frame and loading speed. If the deformation behavior includes elastic deformation as indicated in the adjacent graph it is also often referred to as elastic-plastic or elasto-plastic deformation.

Perfect plasticity is a property of materials to undergo irreversible deformation without any increase in stresses or loads. Plastic materials with hardening necessitate increasingly higher stresses to result in further plastic deformation. Generally plastic deformation is also dependent on the deformation speed, i.e. usually higher stresses have to be applied to increase the rate of deformation and such materials are said to deform visco-plastically.

Contents

Physical mechanisms

Plasticity in metals

Plasticity in a crystal of pure metal is primarily caused by two modes of deformation in the crystal lattice, slip and twinning. Slip is a shear deformation which moves the atoms through many interatomic distances relative to their initial positions. Twinning is the plastic deformation which takes place along two planes due to set of forces applied on a given metal piece.

Slip systems

Main article: Slip (materials science)#Slip systemsCrystalline materials contain uniform planes of atoms organized with long-range order. Planes may slip past each other along their close-packed directions, as is shown on the slip systems wiki page. The result is a permanent change of shape within the crystal and plastic deformation. The presence of dislocations increases the likelihood of planes slipping.

Reversible plasticity

On the nano scale the primary plastic deformation in simple fcc metals is reversible, as long as there is no material transport in form of cross-glide.[8]

Shear banding

The presence of other defects within a crystal may entangle dislocations or otherwise prevent them from gliding. When this happens, plasticity is localized to particular regions in the material. For crystals, these regions of localized plasticity are called shear bands.

Plasticity in amorphous materials

Crazing

In amorphous materials, the discussion of “dislocations” is inapplicable, since the entire material lacks long range order. These materials can still undergo plastic deformation. Since amorphous materials, like polymers, are not well-ordered, they contain a large amount of free volume, or wasted space. Pulling these materials in tension opens up these regions and can give materials a hazy appearance. This haziness is the result of crazing, where fibrils are formed within the material in regions of high hydrostatic stress. The material may go from an ordered appearance to a "crazy" pattern of strain and stretch marks.

Plasticity in martensitic materials

Some materials, especially those prone to Martensitic transformations, deform in ways that are not well described by the classic theories of plasticity and elasticity. One of the best-known examples of this is nitinol, which exhibits pseudoelasticity: deformations which are reversible in the context of mechanical design, but irreversible in terms of thermodynamics.

Plasticity in cellular materials

These materials plastically deform when the bending moment exceeds the fully plastic moment. This applies to open cell foams where the bending moment is exerted on the cell walls. The foams can be made of any material with a plastic yield point which includes rigid polymers and metals. This method of modeling the foam as beams is only valid if the ratio of the density of the foam to the density of the matter is less than 0.3. This is because beams yield axially instead of bending. In closed cell foams, the yield strength is increased if the material is under tension because of the membrane that spans the face of the cells.

Mathematical descriptions of plasticity

Deformation theory

There are several mathematical descriptions of plasticity.[9] One is deformation theory (see e.g. Hooke's law) where the stress tensor (of order d in d dimensions) is a function of the strain tensor. Although this description is accurate when a small part of matter is subjected to increasing loading (such as strain loading), this theory cannot account for irreversibility.

Ductile materials can sustain large plastic deformations without fracture. However, even ductile metals will fracture when the strain becomes large enough - this is as a result of work hardening of the material, which causes it to become brittle. Heat treatment such as annealing can restore the ductility of a worked piece, so that shaping can continue.

Flow plasticity theory

In 1934, Egon Orowan, Michael Polanyi and Geoffrey Ingram Taylor, roughly simultaneously, realized that the plastic deformation of ductile materials could be explained in terms of the theory of dislocations. The more correct mathematical theory of plasticity, flow plasticity theory, uses a set of non-linear, non-integrable equations to describe the set of changes on strain and stress with respect to a previous state and a small increase of deformation.

Yield criteria

Main article: Yield (engineering)If the stress exceeds a critical value, as was mentioned above, the material will undergo plastic, or irreversible, deformation. This critical stress can be tensile or compressive. The Tresca and the von Mises criteria are commonly used to determine whether a material has yielded. However, these criteria have proved inadequate for a large range of materials and several other yield criteria are in widespread use.

Tresca criterion

This criterion is based on the notion that when a material fails, it does so in shear, which is a relatively good assumption when considering metals. Given the principal stress state, we can use Mohr’s circle to solve for the maximum shear stresses our material will experience and conclude that the material will fail if:

Where σ1 is the maximum normal stress, σ3 is the minimum normal stress, and σ0 is the stress under which the material fails in uniaxial loading. A yield surface may be constructed, which provides a visual representation of this concept. Inside of the yield surface, deformation is elastic. On the surface, deformation is plastic. It is impossible for a material to have stress states outside its yield surface.

Huber-von Mises criterion

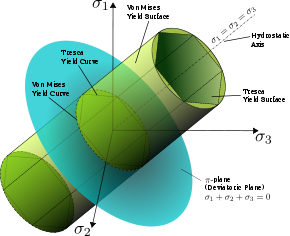

The von Mises yield surfaces in principal stress coordinates circumscribes a cylinder around the hydrostatic axis. Also shown is Tresca's hexagonal yield surface.

The von Mises yield surfaces in principal stress coordinates circumscribes a cylinder around the hydrostatic axis. Also shown is Tresca's hexagonal yield surface. Main article: Von Mises yield criterion

Main article: Von Mises yield criterionThis criterion[10] is based on the Tresca criterion but takes into account the assumption that hydrostatic stresses do not contribute to material failure. M.T. Huber was the first (1904, Lwów) who proposed the criterion of shear energy (see S. P. Timoshenko,p. 77). Von Mises solves for an effective stress under uniaxial loading, subtracting out hydrostatic stresses, and claims that all effective stresses greater than that which causes material failure in uniaxial loading will result in plastic deformation.

Again, a visual representation of the yield surface may be constructed using the above equation, which takes the shape of an ellipse. Inside the surface, materials undergo elastic deformation. Reaching the surface means the material undergoes plastic deformations. It is physically impossible for a material to go beyond its yield surface.

See also

References

- ^ J. Lubliner, 2008, Plasticity theory, Dover, ISBN 0486462900, 9780486462905.

- ^ M. Jirasek and Z. P. Bazant, 2002, Inelastic analysis of structures, John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ W-F. Chen, 2008, Limit Analysis and Soil Plasticity, J. Ross Publishing

- ^ M-H. Yu, G-W. Ma, H-F. Qiang, Y-Q. Zhang, 2006, Generalized Plasticity, Springer.

- ^ W-F. Chen, 2007, Plasticity in Reinforced Concrete, J. Ross Publishing

- ^ J. A. Ogden, 2000, Skeletal Injury in the Child, Springer.

- ^ J-L. Leveque and P. Agache, ed., 1993, Aging skin:Properties and Functional Changes, Marcel Dekker.

- ^ Gerolf Ziegenhain and Herbert M. Urbassek: Reversible Plasticity in fcc metals. In: Philosophical Magazine Letters. 89(11):717-723, 2009 DOI

- ^ R. Hill, 1998, The Mathematical Theory of Plasticity, Oxford University Press.

- ^ von Mises, R. (1913). Mechanik der Festen Korper im plastisch deformablen Zustand. Göttin. Nachr. Math. Phys., vol. 1, pp. 582–592.

Further reading

- R. Hill, The Mathematical Theory of Plasticity, Oxford University Press (1998).

- Jacob Lubliner, Plasticity Theory, Macmillan Publishing, New York (1990).

- L. M. Kachanov, Fundamentals of the Theory of Plasticity, Dover Books.

- A.S. Khan and S. Huang, Continuum Theory of Plasticity, Wiley (1995).

- J. C. Simo, T. J. Hughes, Computational Inelasticity, Springer.

- M. F. Ashby. Plastic Deformation of Cellular Materials. Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology, Elsevier, Oxford, 2001, Pages 7068-7071.

- Van Vliet, K. J., 3.032 Mechanical Behavior of Materials, MIT (2006)

- International Journal of Plasticity, Elsevier Science.

- S. P. Timoshenko, History of strength of materials, New York,Toronto,London, McGraw-Hill Book Company,inc., 1953.

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

![\begin{align}\sigma_{\mathrm{effective}}^2 & = \tfrac{1}{2} \left [ \left (\sigma_{11} - \sigma_{22} \right )^2 + \left (\sigma_{22} - \sigma_{33} \right )^2

+ \left (\sigma_{11} - \sigma_{33} \right)^2 \right ] \\

& \qquad + 6 \left(\sigma_{12}^2 + \sigma_{13}^2 + \sigma_{23}^2 \right )\end{align}](b/8ab61e954d6ad4ac2904f4310b6c0a4a.png)