- Iron(III) oxide

-

Iron(III) oxide

Identifiers CAS number 1309-37-1

PubChem 518696 ChemSpider 21106565

UNII 1K09F3G675

ChEBI CHEBI:50819

RTECS number NO7400000 Jmol-3D images Image 1 - O1[Fe]2O[Fe]1O2

Properties Molecular formula Fe2O3 Molar mass 159.69 g/mol Appearance red-brown solid Odor odorless Density 5.242 g/cm3, solid Melting point 1566 °C (1838 K) decomp.

Solubility in water insoluble Structure Crystal structure rhombohedral Thermochemistry Std enthalpy of

formation ΔfHo298−825.50 kJ/mol Hazards EU classification not listed Flash point non-flammable Related compounds Other anions iron(III) fluoride Other cations manganese(III) oxide, cobalt(III) oxide Related compounds iron(II) oxide, iron(II,III) oxide  oxide (verify) (what is:

oxide (verify) (what is:  /

/ ?)

?)

Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa)Infobox references Iron(III) oxide or ferric oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula Fe2O3. It is one of the three main oxides of iron, the other two being iron(II) oxide (FeO), which is rare, and iron(II,III) oxide (Fe3O4), which also occurs naturally as the mineral magnetite. As the mineral known as hematite, Fe2O3 is the main source of the iron for the steel industry. Fe2O3 is ferromagnetic, dark red, and readily attacked by acids. Rust is often called iron(III) oxide, and to some extent this label is useful, because rust shares several properties and has a similar composition. To a chemist, rust is considered an ill-defined material, described as hydrated ferric oxide.

Contents

Structure

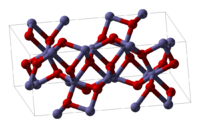

Fe2O3 can be obtained in various polymorphs. In the main ones, α and γ, iron adopts octahedral coordination geometry. That is, each Fe centre is bound to six oxygen ligands.

Alpha phase

α-Fe2O3 has the rhombohedral, corundum (α-Al2O3) structure and is the most common form. In this structure, . It occurs naturally as the mineral hematite which is mined as the main ore of iron. It is antiferromagnetic below ~260 K (Morin transition temperature), and weak ferromagnetic between 260 K and 950 K Néel temperature.[1] It is easy to prepare using both thermal decomposition and precipitation in the liquid phase. Its magnetic properties are dependent on many factors, e.g. pressure, particle size, and magnetic field intensity.

Gamma phase

Cubic, metastable, converts to the alpha phase at high temperatures. Occurs naturally as the mineral maghemite. Ferromagnetic. Ultrafine particles smaller than 10 nanometers are superparamagnetic. Can be prepared by thermal dehydratation of gamma iron(III) oxide-hydroxide, careful oxidation of iron(II,III) oxide. The ultrafine particles can be prepared by thermal decomposition of iron(III) oxalate.[citation needed]

Other phases

Several other phases have been identified or claimed. The beta-phase is cubic face centered, metastable, at temperatures above 500 °C (930 °F) converts to alpha phase. It can be prepared by reduction of hematite by carbon, pyrolysis of iron(III) chloride solution, or thermal decomposition of iron(III) sulfate. The epsilon phase is rhombic, shows properties intermediate between alpha and gamma. So far has not been prepared in pure form; it is always mixed with the alpha phase or gamma phases. Material with a high proportion of epsilon phase can be prepared by thermal transformation of the gamma phase. This phase is also metastable, transforming to the alpha phase at between 500 and 750 °C (930 and 1,380 °F). Can also be prepared by oxidation of iron in an electric arc or by sol-gel precipitation from iron(III) nitrate.[citation needed] Additionally at high pressure an amorphous form is claimed.[2]

Reactions

The most important reaction is its carbothermal reduction, which gives iron used in steel-making:

- 2 Fe2O3 + 3 C → 4 Fe + 3 CO2

Another redox reaction is the extremely exothermic thermite reaction with aluminium.[3]

This process is used to weld thick metals such as rails of train tracks by using a ceramic container to funnel the molten iron in between two sections of rail. Thermite is also used in weapons and making small-scale cast-iron sculptures and tools.

Partial reduction with hydrogen at about 400 C gives magnetite, a black magnetic material that contains both Fe(III) and Fe(II):[4]

- 3 Fe2O3 + H2 → 2 Fe3O4 + H2O

Iron(III) oxide is insoluble in water but dissolves readily in strong acid, e.g. hydrochloric and sulfuric acids. It also dissolves well in solutions of the chelating agents such as EDTA and oxalic acid.

Heating iron(III) oxides with other metal oxides or carbonates yields materials known as ferrates:[4]

- ZnO + Fe2O3 → Zn(FeO2)2

Preparation

Iron (III) oxide is a product of the oxidation of iron. It can be prepared in the laboratory by electrolyzing a solution of sodium bicarbonate, an inert electrolyte, with an iron anode:

- 4 Fe + 3 O2 + 2 H2O → 4 FeO(OH)

The resulting hydrated iron(III) oxide, written here as Fe(O)OH, dehydrates around 200 ÷C.[4][5]

- 2 FeO(OH) → Fe2O3 + H2O

Uses

Iron industry

The overwhelming application of Iron(III) oxide is as the feedstock of the steel and iron industries, e.g. the production of iron, steel, and many alloys.[5]

Polishing

A very fine powder of ferric oxide is known as "jeweler's rouge", "red rouge", or simply rouge. It is used to put the final polish on metallic jewelry and lenses, and historically as a cosmetic.

Rouge cuts more slowly than some modern polishes, such as cerium(IV) oxide, but is still used in optics fabrication and by jewelers for the superior finish it can produce. When polishing gold, the rouge slightly stains the gold, which contributes to the appearance of the finished piece. Rouge is sold as a powder, paste, laced on polishing cloths, or solid bar (with a wax or grease binder). Other polishing compounds are also often called "rouge", even when they do not contain iron oxide. Jewelers remove the residual rouge on jewelry by use of ultrasonic cleaning.

Tool Sharpening

Products sold as stropping compound are often applied to a leather strop to assist in getting a razor edge on knives, straight razors, or any other edged tool.

Pigment

Iron(III) oxide is also used as a pigment, under names "Pigment Brown 6", "Pigment Brown 7", and "Pigment Red 101".[6] Some of them, e.g. Pigment Red 101 and Pigment Brown 6, are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for use in cosmetics.

Niche uses

Being inexpensive and nontoxic, ferric oxide finds many niche uses. For example, in its granular form (GFO, granular-ferric-oxide), it is used to remove phosphates in aquariums. The crystals are also used, due to their ferromagnetism, in audio tapes, as the level of magnetism records the frequency of sound to be recorded[7].

See also

- Iron oxides

References

- ^ Greedon, J. E. (1994). "Magnetic oxides". In King, R. Bruce. Encyclopedia of Inorganic chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-93620-0.

- ^ "Oxid železitý, Fe2O3" (in Czech). http://atmilab.upol.cz/vys/fe2o3.html. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Adlam; Price (1945). Higher School Certificate Inorganic Chemistry. Leslie Slater Price.

- ^ a b c Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1661.

- ^ a b Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Element (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- ^ Paint and Surface Coatings: Theory and Practice. William Andrew Inc.. ISBN 1-884207-73-1.

- ^ Kotz, Treichel, Townsend (2009), Chemistry & Chemical Reactivity (7th edition) (Instructor's Edition), Thomson Brooks/Cole, ISBN-13 978-0-495-38710-7

External links

Iron compounds Categories:- Iron compounds

- Oxides

- Iron oxide pigments

- Common oxide glass components

- Sesquioxides

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.