- Bullfighting

-

"bull fighting" redirects here. For the Taiwanese TV series, see Bull Fighting (TV series). For the rodeo performer, see bullfighter (rodeo).

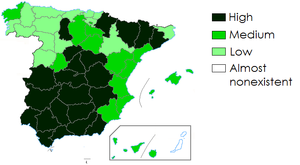

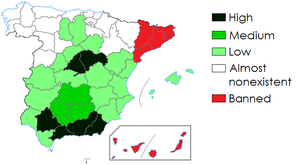

Bullfighting in provinces of Spain at 2010.

Bullfighting in provinces of Spain at 2010.

• Exceptions should be noted, such as the area of Pamplona in northern Navarre, with major bullfighting.

• In 1991, the Canary Islands became the first Spanish Autonomous Community to ban bullfighting, and Catalonia will become the second in January 2012.Bullfighting (also known as tauromachia or tauromachy; from Greek: ταυρομαχία "bull-fight";[1] Spanish: toreo, IPA: [to'reo]; Portuguese: tourada, IPA: [toˈɾaðɐ]) is a traditional spectacle of Spain, Portugal, southern France and some Latin American countries (Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru and Ecuador),[2] in which one or more bulls are baited in a bullring for sport and entertainment. It is often called a blood sport by its detractors but followers of the spectacle regard it as a fine art and not a sport as there are no elements of competition in the proceedings. In Portugal it is illegal to kill a bull in the arena, so it is removed and slaughtered in the pens as fighting bulls can only be used once. A non-lethal variant stemming from Portuguese influence is also practised on the Tanzanian island of Pemba.[3]

The tradition, as it is practised today, involves professional toreros (also called toreadors) who execute various formal moves which can be interpreted and innovated according to the bullfighter's style or school. Toreros seek to elicit inspiration and art from their work and an emotional connection with the crowd transmitted through the bull. Such manoeuvres are performed at close range, which places the bullfighter at risk of being gored or trampled. After the bull has been hooked multiple times behind the shoulder by other matadors in the arena the bullfight usually concludes with the killing of the bull by a single sword thrust which is called estocada. In Portugal the finale consists of a tradition called the pega, where men (forcados) try to grab and hold the bull by its horns when it runs at them.

Supporters of bullfighting argue that it is a culturally important tradition and a fully developed art form on par with painting, dancing and music, while animal rights advocates hold that it is a blood sport resulting in the suffering of bulls and horses.

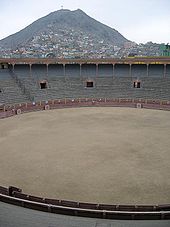

There are many historic fighting venues in the Iberian Peninsula, France and Latin America. The largest venue of its kind is the Plaza México in central Mexico City, which seats 48,000 people,[4] and the oldest is the La Maestranza in Sevilla, Spain, which was first used for bullfighting in 1765.[5]

Contents

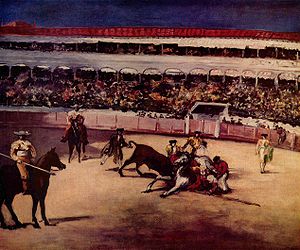

History

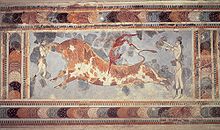

Bullfighting traces its roots to prehistoric bull worship and sacrifice. The killing of the sacred bull (tauroctony) is the essential central iconic act of Mithras, which was commemorated in the mithraeum wherever Roman soldiers were stationed. The oldest representation of what seems to be a man facing a bull is on the celtiberian tombstone from Clunia and the cave painting "El toro de hachos", both found in Spain.[6][7]

Bullfighting is often linked to Rome, where many human-versus-animal events were held. There are also theories that it was introduced into Hispania by the Emperor Claudius, as a substitute for gladiators, when he instituted a short-lived ban on gladiatorial combat. The latter theory was supported by Robert Graves. (Picadors are the remnants of the javelin, but their role in the contest is now a relatively minor one limited to "preparing" the bull for the matador.) Bullfighting spread from Spain to its Central and South American colonies, and in the 19th century to France, where it developed into a distinctive form in its own right.

Religious festivities and royal weddings were celebrated by fights in the local plaza, where noblemen would ride competing for royal favor, and the populace enjoyed the excitement. The Spanish introduced the practice of fighting on foot around 1726. Francisco Romero is generally regarded as having been the first to do this.

This type of fighting drew more attention from the crowds. Thus the modern corrida, or fight, began to take form, as riding noblemen were substituted by commoners on foot. This new style prompted the construction of dedicated bullrings, initially square, like the Plaza de Armas, and later round, to discourage the cornering of the action. The modern style of Spanish bullfighting is credited to Juan Belmonte, generally considered the greatest matador of all time. Belmonte introduced a daring and revolutionary style, in which he stayed within a few inches of the bull throughout the fight. Although extremely dangerous (Belmonte himself was gored on many occasions), his style is still seen by most matadors as the ideal to be emulated. Today, bullfighting remains similar to the way it was in 1726, when Francisco Romero, from Ronda, Spain, used the estoque, a sword, to kill the bull, and the muleta, a small cape used in the last stage of the fight.

Styles of bullfighting

Originally, there were at least five distinct regional styles of bullfighting practised in southwestern Europe: Andalusia, Aragon–Navarre, Alentejo, Camargue, Aquitaine. Over time, these have evolved more or less into standardized national forms mentioned below. The "classic" style of bullfight, in which the bull is killed, is the form practised in Spain and many Latin American countries.

Spanish-style bullfighting

Spanish-style bullfighting is called corrida de toros (literally "running of bulls") or la fiesta ("the festival"). In a traditional corrida, three matadores, each fight two bulls, each of which is between four and six years old and weighs no less than 460 kg (1,014 lb) [8] Each matador has six assistants—two picadores ("lancers on horseback") mounted on horseback, three banderilleros – who along with the matadors are collectively known as toreros ("bullfighters") – and a mozo de espadas ("sword page"). Collectively they comprise a cuadrilla ("entourage"). The word "matador" is only used in English whereas in Spanish the more general "torero" is used and only when needed to distinguish the full title "matador de toros" is used.

Start of tercio de varas : polished verónica and larga serpentina during a goyesca corrida. Welcoming of a toro a porta gayola and series of verónica terminated by a semi-verónica.

Welcoming of a toro a porta gayola and series of verónica terminated by a semi-verónica.

The modern corrida is highly ritualized, with three distinct stages or tercios ("thirds"), the start of each being announced by a bugle sound. The participants first enter the arena in a parade, called the paseíllo, to salute the presiding dignitary, accompanied by band music. Torero costumes are inspired by 17th century Andalusian clothing, and matadores are easily distinguished by the gold of their traje de luces ("suit of lights") as opposed to the lesser banderilleros who are also called toreros de plata ("bullfighters of silver"). Next, the bull enters the ring to be tested for ferocity by the matador and banderilleros with the magenta and gold capote ("cape"). This is the first stage, the tercio de varas ("the lancing third"), and the matador first confronts the bull with the capote, performing a series of passes and observing the behavior and quirks of the bull.

Next, a picador enters the arena on horseback armed with a vara ("lance"). To protect the horse from the bull's horns, the horse is surrounded by a protective, padded covering called "peto". Prior to 1930, the horse did not wear any protection, and the bull would usually disembowel the horse during this stage. Until this change was instituted, the number of horses killed during a fight was higher than the number of bulls killed.[9]

At this point, the picador stabs just behind the morrillo, a mound of muscle on the fighting bull's neck, weakening the neck muscles and leading to the animal's first loss of blood. The manner in which the bull charges the horse provides important clues to the matador about which side the bull favors. If the picador is successful, the bull will hold its head and horns slightly lower during the following stages of the fight. This ultimately enables the matador to perform the killing thrust later in the performance. The encounter with the picador often fundamentally changes the behaviour of a bull, distracted and unengaging bulls will become more focused and stay on a single target instead of charging at everything that moves.

In the next stage, the tercio de banderillas ("the third of banderillas"), the three banderilleros each attempt to plant two banderillas, sharp barbed sticks into the bull's shoulders. These anger and invigorate, but further weaken, the bull who has been tired by his attacks on the horse and the damage he has taken from the lance. Sometimes a matador will place his own banderillas. If they do so they usually embellish this part of their performance and employ more varied manoeuvres than the standard "al cuarteo" method usually used by Banderilleros that are part of a Matador's cuadrilla.

In the final stage, the tercio de muerte ("the third of death"), the matador re-enters the ring alone with a small red cape, or muleta, and a sword. It is a common misconception that the color red is supposed to anger the bull, because bulls, in fact, are colorblind.[10][11] The cape is thought to be red to mask the bull's blood, although this is now also a matter of tradition. The matador uses his cape to attract the bull in a series of passes which serve the dual purpose of wearing the animal down for the kill and producing a beautiful display or faena. He may also demonstrate his domination over the bull by caping it especially close to his body. The faena is the entire performance with the muleta and it is usually broken down into tandas, "series", of passes. The faena ends with a final series of passes in which the matador with a muleta attempts to maneuver the bull into a position to stab it between the shoulder blades and through the aorta or heart. The sword is called "estoque" and the act of thrusting the sword is called an estocada. The estoque used by the matador during the faena is called estoque simulado. This estoque simulado is made out of wood or aluminum. In contrast to the estoque de verdad (real sword) which is made out of steel and is used for the estocada the estoque simulado is lighter and therefore much easier to handle. However, at the end of the tercio de muerte at the time when the matador has finished his faena the matador will change his estoque simolado for the estoque de verdad to perform the estocada.

If the matador has performed particularly well, the crowd may petition the president to award the matador an ear of the bull by waving white handkerchiefs. If his performance was exceptional, he will award two, and in certain more rural rings a tail can still be awarded. Very rarely, if the public or the matador believe that the bull has fought extremely bravely, they may petition the president of the event to grant the bull a pardon (indulto) and if granted the bull's life is spared and it is allowed to leave the ring alive and return to the ranch where it came from. Then the bull becomes a stud bull for the rest of its life.

Recortes

Recortes, a style of bullfighting practised in Navarre, La Rioja, North of Castile and Valencia, has been far less popular than the traditional corridas. There has been a recent resurgence of recortes in Spain where they are sometimes shown on TV.

This style was common in the early 19th century. Etchings by painter Francisco de Goya depict these events.

Recortes claims to differ from a corrida in the following ways:

- The bull is not physically injured. Drawing blood is rare and the bull returns to his pen at the end of the performance.

- The men are dressed in common street clothes and not in traditional bullfighting dress.

- Acrobatics are performed without the use of capes or other props. Performers attempt to evade the bull solely through the swiftness of their movements.

- Rituals are less strict so the men have freedom to perform stunts as they please.

- Men work in teams but with less role distinction than in a corrida.

- Teams compete for points awarded by a jury.

Animal rights groups such as PETA object to recortes;[citation needed] however, some people[who?] find recortes less objectionable than traditional bullfighting since the bull survives the ordeal. Since horses are not used, and performers are not professionals, recortes are less costly to produce.

Portuguese

Most Portuguese bullfights are held in two phases: the spectacle of the cavaleiro, and the pega. In the cavaleiro, a horseman on a Portuguese Lusitano horse (specially trained for the fights) fights the bull from horseback. The purpose of this fight is to stab three or four bandeiras (small javelins) in the back of the bull.

In the second stage, called the pega ("holding"), the forcados, a group of eight men, challenge the bull directly without any protection or weapon of defence. The front man provokes the bull into a charge to perform a pega de cara or pega de caras (face grab). The front man secures the animal's head and is quickly aided by his fellows who surround and secure the animal until he is subdued.[12] Forcados are dressed in a traditional costume of damask or velvet, with long knitted hats as worn by the campinos (bull headers) from Ribatejo.

The bull is not killed in the ring and, at the end of the corrida, leading oxen are let into the arena and two campinos on foot herd the bull among them back to its pen. The bull is usually killed, away from the audience's sight, by a professional butcher. It can happen that some bulls, after an exceptional performance, are healed, released to pasture until their end days and used for breeding.

French

Since the 19th century Spanish-style corridas have been increasingly popular in Southern France where they enjoy legal protection in areas where there is an uninterrupted tradition of such bull fights, particularly during holidays such as Whitsun or Easter. Among France's most important venues for bullfighting are the ancient Roman arenas of Nîmes and Arles, although there are bull rings across the South from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic coasts. The French version of bullfighting is unique in that the bulls have a choice not to fight.

A more indigenous genre of bullfighting is widely common in the Provence and Languedoc areas, and is known alternately as "course libre" or "course camarguaise". This is a bloodless spectacle (for the bulls) in which the objective is to snatch a rosette from the head of a young bull. The participants, or raseteurs, begin training in their early teens against young bulls from the Camargue region of Provence before graduating to regular contests held principally in Arles and Nîmes but also in other Provençal and Languedoc towns and villages. Before the course, an encierro—a "running" of the bulls in the streets—takes place, in which young men compete to outrun the charging bulls. The course itself takes place in a small (often portable) arena erected in a town square. For a period of about 15–20 minutes, the raseteurs compete to snatch rosettes (cocarde) tied between the bulls' horns. They do not take the rosette with their bare hands but with a claw-shaped metal instrument called a raset or crochet (hook) in their hands, hence their name. Afterwards, the bulls are herded back to their pen by gardians (Camarguais cowboys) in a bandido, amidst a great deal of ceremony. The star of these spectacles are the bulls, who get top billing and stand to gain fame and statues in their honor, and lucrative product endorsement contracts.[13]

Another type of French 'bullfighting' is the "course landaise" style, in which cows are used instead of bulls. This is a competition between teams named cuadrillas, which belong to certain breeding estates. A cuadrilla is made up of a teneur de corde, an entraîneur, a sauteur, and six écarteurs. The cows are brought to the arena in boxes and then taken out in order. Teneur de corde controls the dangling rope attached to cow's horns and the entraîneur positions the cow to face and attack the player. The écarteurs will try, at the last possible moment, to dodge around the cow and the sauteur will leap over it. Each team aims to complete a set of at least one hundred dodges and eight leaps. This is the main scheme of the "classic" form, the course landaise formelle. However, different rules may be applied in some competitions. For example, competitions for Coupe Jeannot Lafittau are arranged with cows without ropes.

At one point it resulted in so many fatalities that the French government tried to ban it, but had to back down in the face of local opposition. The bulls themselves are generally fairly small, much less imposing than the adult bulls employed in the corrida. Nonetheless, the bulls remain dangerous due to their mobility and vertically formed horns. Participants and spectators share the risk; it is not unknown for angry bulls to smash their way through barriers and charge the surrounding crowd of spectators. The course landaise is not seen as a dangerous sport by many, but écarteur Jean-Pierre Rachou died in 2003 when a bull's horn tore his femoral artery.

Tamil Nadu or Indian style – Jallikattu

Jallikattu or Sallikattu -சல்லிகட்டு or Eruthazhuvuthal -ஏருதழுவுதல் is a bull-taming sport played in Tamil Nadu as a part of Pongal celebration. It is one of the oldest in the modern era. Although it sounds similar to the Spanish running of the bulls, it is different. In Jallikattu, the bull is not killed and the 'matadors' are not supposed to use any weapon. It is held in the villages of Tamil Nadu as a part of the village festivals held from January to July, every year. The one held in Alanganallur, near Madurai, is one of the more popular events. This sport is also known as "Manju Virattu", meaning "chasing the bull".

Understanding Jallikattu or Manju Virattu: Jallikattu is based on the simple concept of "flight or fight". Cattle are herd and prey animals and run away from dangerous situations, but there are exceptions. Cape buffalos stand up against lions and often kill them. The Indian Gaur bull is known for standing its ground against predators and tigers are wary of attacking a full grown Gaur bull. Aurochs, the ancestors of domestic cattle, were known for their pugnacious nature. Jallikattu bulls belong to a few specific breeds of cattle that descended from the kangayam breed of cattle and these cattle are pugnacious by nature. These cattle are reared in large herds numbering in the hundreds, with a few cowherds tending to them. These cattle are for all practical comparisons, wild and only the cowherds can mingle with them without fear of being attacked. It is from these herds that calves with good characteristics and body conformation are selected and reared to become jallikattu bulls. These bulls attack not because they are irritated or agitated or frightened, but because that is their basic nature.

There are three versions of Jallikattu:

- Vadi manju virattu – this version takes place mostly in the districts of Madurai, Pudukkottai, Theni, Tanjore, and Salem. It has been popularised by television and films and involves the bull being released from an enclosure through an opening. As the bull comes out of the enclosure, one person clings to the hump of the bull. The bull in its attempt to shake him off will bolt in most cases, but some will hook the man with their horns and throw him off. The rules specify that the person has to hold on to the running bull for a predetermined distance to win the prize. In this version, only one person is supposed to attempt catching the bull. Some bulls acquire a reputation and that is enough for them to be given a unhindered passage out of the enclosure and arena.

- Vaeli virattu – this version is more popular in the districts of sivagangai, manamadurai and madurai. The bull is released in an open ground. This version is the most natural, as the bulls are not restricted in any way (no rope or determined path). The bulls once released simply run away from the field in any direction. Most do not even come close to any human. There are a few bulls that do not run but stand their ground and attack anyone who tries to come near them. These bulls will "play" for some time (from a few minutes to several hours) providing a spectacle for viewers, players and owners alike.

- Vadam manjuvirattu – "vadam" means rope in Tamil. The bull is tied to a 50-foot-long rope (15 m) and is free to move within this space. A team of seven or nine members must attempt to subdue the bull within 30 minutes. This version is safe for spectators, as the bull is tied and the spectators are shielded by barricades.

Training of jallikattu bulls: the calves that are chosen to become jallikattu bulls are fed a nutritious diet so they develop into strong, sturdy beasts. The bulls are made to swim for exercise. The calves, once they reach adolescence are taken to small jallikattu events to familiarise them with the atmosphere. Specific training is given to vadam manju virattu bulls to understand the restraints of the rope. Apart from this, no other training is provided to jallikattu bulls.

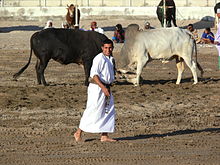

Bullfighting in Oman

Oman is perhaps the only country in the Persian Gulf and the Arab world in which bullfighting is carried out. In the interiors of the country, temporary bullrings are set up for the events. Al-Batena area is prominent for such events. Wide audiences turn up to see the events unfold. Omani bullfighting is however not a violent event. The origins of bullfighting in Oman are unknown, though locals believe it was brought to Oman by the Moors who had conquered Spain. Its existence is also attributed to Portugal which colonized the Omani coastline for nearly two centuries.[14]

Freestyle bullfighting

Main article: Bullfighter (rodeo)Freestyle bullfighting is a style of bullfighting developed in American rodeo. The style was developed by the rodeo clowns who protect bull riders from being trampled or gored by an angry bull. Freestyle bullfighting is a 70-second competition in which the bullfighter (rodeo clown) avoids the bull by means of dodging, jumping and use of a barrel. Competitions are organized in the US as the World Bullfighting Championship (WBC) and the Dickies National Bullfighting Championship under auspices of the Professional Bull Riders (PBR).

Comic bullfighting

Comical spectacles based on bullfighting, called espectáculos cómico-taurinos or charlotadas, are still popular in Spain and Mexico, with troupes like El empastre or El bombero torero.[15]

Hazards

Spanish-style bullfighting is normally fatal for the bull but it is also dangerous for the matador. Picadors and banderilleros are sometimes gored, but this is not common.

Some matadors, notably Juan Belmonte, have been gored many times: according to Ernest Hemingway, Belmonte's legs were marred by many ugly scars. A special type of surgeon has developed, in Spain and elsewhere, to treat cornadas, or horn-wounds.

The bullring has a chapel where a matador can pray before the corrida, and where a priest can be found in case a sacrament is needed. The most relevant sacrament is now called "Anointing of the Sick"; it was formerly known as "Extreme Unction", or the "Last Rites".

The media often reports the more horrific of bullfighting injuries, such as the May 2010 piercing of matador Julio Aparicio Díaz's chin by a bull's horn.[16]

Cultural aspects

Many supporters of bullfighting regard it as a deeply ingrained, integral part of their national cultures. The aesthetic of bullfighting is based on the interaction of the man and the bull. Rather than a competitive sport, the bullfight is more of a ritual which is judged by aficionados (bullfighting fans) based on artistic impression and command. Ernest Hemingway said of it in his 1932 non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon: "Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter's honour." Bullfighting is seen as a symbol of Spanish culture.

The bullfight is above all about the demonstration of style, technique and courage by its participants. While there is usually no doubt about the outcome, the bull is not viewed as a sacrificial victim—it is instead seen by the audience as a worthy adversary, deserving of respect in its own right.

Those who oppose bullfighting maintain that the practice is merely a cowardly, sadistic tradition of slowly torturing, humiliating and finally murdering a terrified, dying bull who vomits blood, bellows in agony, and desperately seeks his escape amid pomp and pageantry of unashamed people who applaud when he finally collapses and then is killed.[17] Supporters of bullfights, called "aficionados," claim they respect the bulls and that bullfighting is a grand tradition; a form of art important to their culture.[18]

Popularity, controversy and criticism

Public opinion

A 2002 Gallup poll found that 68.8% of Spaniards express "no interest" in bullfighting while 20.6% expressed "some interest" and 10.4% "a lot of interest". The poll also found significant generational variety, with 51% of those 65 and older expressing interest, compared with 23% of those between 25 and 34 years of age. Popularity also varies significantly according to regions in Spain with it being least popular in Galicia and Catalonia with 79% and 81% of those polled expressing no interest. Interest is greatest in the zones of the north, centre, east and south, with around 37% declaring themselves fans and 63% having no interest.[19]

According to a poll conducted by the Sports Marketing Group in Atlanta in 2003, 46.2% of Americans polled hated or strongly disliked bull fighting.[20]

Animal rights

Bullfighting is criticized by animal rights activists, referring to it as a cruel or barbaric blood sport, in which the bull suffers severe stress and a slow, torturous death.[21][22][23][24] A number of animal rights or animal welfare activist groups undertake anti-bullfighting actions in Spain and other countries. In Spanish, opposition to bullfighting is referred to as antitaurina.

Bullfighting guide The Bulletpoint Bullfight warns that bullfighting is "not for the squeamish", advising spectators to "be prepared for blood." The guide details prolonged and profuse bleeding caused by horse-mounted lancers, the charging by the bull of a blindfolded, armored horse who is "sometimes doped up, and unaware of the proximity of the bull", the placing of barbed darts by banderilleros, followed by the matador's fatal sword thrust. The guide stresses that these procedures are a normal part of bullfighting and that death is rarely instantaneous. The guide further warns those attending bullfights to "Be prepared to witness various failed attempts at killing the animal before it lies down."[25]

Funding

A ticket stub from 1926

A ticket stub from 1926

It has also been noted by critics that bullfighting is financed with public money.[26] In 2007, the Spanish fighting bull breeding industry was allocated 500 million euros in grants,[27] and in 2008 almost 600 million.[28] Some of this money comes from European funds to livestock.[29] Bullfighting supporters argue that almost every single cultural endeavour in Europe is partially financed by public money and few of them generate the kind of revenue and taxes in return that bullfighting does through its impact on businesses like hotels, restaurants, insurances and other industries directly or indirectly linked to the spectacle.

Style

Another current of criticism comes from aficionados themselves, who may despise modern developments such as the defiant style ("antics" for some) of El Cordobés or the lifestyle of Jesulín de Ubrique, a common subject of Spanish gossip magazines. His "female audience"-only corridas were despised by veterans, many of whom reminisce about times past, comparing modern bullfighters with early figures.[citation needed]

Politics

Late 19th century / early 20th century Fin-de-siècle Spanish regeneracionista intellectuals protested against what they called the policy of pan y toros ("bread and bulls"), an analogue of Roman panem et circenses promoted by politicians to keep the populace content in its oppression. During the Franco dictatorship bullfights were supported by the state as something genuinely Spanish, as the fiesta nacional, so that bullfights became associated with the regime and, for this reason, many thought they would decline after the transition to democracy, but this did not happen. Later social-democratic governments, particularly the current government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, have generally been more opposed to bullfighting, prohibiting children under 14 from attending and limiting or prohibiting the broadcast of bullfights on national TV.

Some in Spain despise bullfighting because of its association with the Spanish nation and the Franco regime.[30] Despite the long history and popularity of bullfighting in Barcelona, in 2010 it was banned in the Catalonia region, although this move has been criticized by some as being motivated by issues of Catalan independentism rather than animal rights, even when the law that banned it was proposed by an animal rights civic platform called "Prou!" ("Enough!" in Catalan).[31]

The Spanish Royal Family is divided on the issue, from Queen Sophia who does not hide her dislike for bullfights,[32] to King Juan Carlos who occasionally presides over a bullfight from the royal box as part of his official duties,[33][34][35] to their daughter Princess Elena who is well known for her liking of bullfights and who often accompanies the king in the presiding box or attends privately in the general seating.[36] The King has allegedly stated, that "the day the EU bans bullfighting is the day Spain leaves the EU".[37]

Religion

Judaism

In Judaism, the Talmud (Nezikin: Avodah Zarah) discusses the Rabbis' warning against visiting "stadiums and circuses." Prominent eleventh-century scholar Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki (Rashi) interpreted "stadiums" as referring to "a place where they taunt the bull." Eighteenth-century scholar Rabbi Yechezkel Landau (Noda' BiYehuda) was asked if one may hunt for sport. He answered that one may not, for it involves putting oneself in danger and is a demonstration of cruelty toward animals. Former Chief Rabbi of Israel Rav Ovadia Yosef was asked specifically if one may watch a bullfight. He answered that it is forbidden: one must not go to places where performing acts of cruelty against animals is made into a form of amusement.[38]

Islam

Housni al-Khateeb Shehada, an Israeli college lecturer on Islamic art and culture, analyzed the responses of Sunni jurists at IslamOnline to inquiries relating to animal cruelty and concluded that there is a strict prohibition against tormenting animals for purposes of amusement, entertainment, or spectator sport – including bullfighting.[39]

Media prohibitions

State-run Spanish TVE cancelled live coverage of bullfights in August 2007, claiming that the coverage was too violent for children who might be watching, and that live coverage violated a voluntary, industry-wide code attempting to limit "sequences that are particularly crude or brutal".[40] In October 2008, in a statement to Congress, Luis Fernández, the President of Spanish State Broadcaster TVE, confirmed that the station will no longer broadcast live bullfights due to the high cost of production and a rejection of the events by advertisers. However the station will continue to broadcast 'Tendido Cero', a bullfighting magazine programme.[41] Having the national Spanish TV stop broadcasting it, after 50 years of history, was considered a big step for its abolition. Nevertheless, other regional and private channels keep broadcasting it with good audiences.[42]

A Portuguese television station also prohibited the broadcasting of bullfights in January 2008, because they are too violent for minors.[43] In March 2009, Viana do Castelo, a city in northern Portugal, became the first city in that country to ban bullfighting. Mayor Defensor Moura cited torture and imposition of unjustifiable suffering as a factor in arriving at the ban. The city's bullfighting arena will be torn down to accommodate a new cultural centre.[44]

Bans

Pre-20th century

Pope Pius V issued a papal bull titled De Salute Gregis in November 1567 which forbade fighting of bulls and any other beasts as the voluntary risk to life endangered the soul of the combatants, but it was abolished eight years later by his successor, Pope Gregory XIII, at the request of king Philip II.

Bullfighting was introduced in Uruguay in 1776 by Spain and abolished by Uruguayan law in February 1912. Bullfighting was also introduced in Argentina by Spain but after Argentina's independence the event drastically diminished in popularity and was abolished in 1899 under law 2786.[45]

Bullfighting also saw a presence in Cuba during its colonial period but was quickly abolished after its independence in 1901.

During the 18th and 19th centuries bullfighting in Spain was banned at several occasions (for instance by Philip V) but always reinstituted later by other governments.

20th century onwards

Bullfighting is now banned in many countries; people taking part in such activity would be liable for terms of imprisonment for animal cruelty. "Bloodless" variations, though, are permitted and have attracted a following in California and France.[46]

In 1991, the Canary Islands became the first Spanish Autonomous Community to ban bullfighting,[31] when they legislated to ban bullfights and other spectacles that involve cruelty to animals, with the exception of cockfighting, which is traditional in some towns in the Islands.[47] Some supporters of bullfighting and even Lorenzo Olarte Cullen,[48] Canarian head of government at the time, have argued that the fighting bull is not a "domestic animal" and hence the law does not ban bullfighting.[49] The absence of spectacles since 1984 would be due to lack of demand. In the rest of Spain, national laws against cruelty to animals have abolished most blood sports, but specifically exempt bullfighting.

Several cities around the world have symbolically declared themselves to be Anti-Bullfighting Cities, including Barcelona, where the last bullfighting ring closed in 2006.[50]

Ecuador

Ecuador staged bullfights to the death for over three centuries due to being a former Spanish colony.

On 17 December 2010 Ecuador's president Rafael Correa announced that in a upcoming referendum, the country will be asked whether to ban bullfighting.[51][52][53]

In a referendum in May 2011, the Ecuadorians agreed on banning the final killing of the bull that happens in a corrida.[54]

Catalonia

Main article: Ban on bullfighting in CataloniaOn 18 December 2009, the parliament of Catalonia, one of Spain's seventeen Autonomous Communities, approved by majority the preparation of a law to ban bullfighting in Catalonia, as a response to a popular initiative against bullfighting that gathered more than 180,000 signatures.[55] On 28 July 2010, with the two main parties allowing their members a free vote, the ban was passed 68 to 55, with 9 abstentions. This meant Catalonia became the second Community of Spain (first was Canary Islands in 1991), and the first on the mainland, to ban bullfighting. The ban takes effect in January 2012, and would only affect the one remaining functioning Catalonian bullring, the Plaza de toros Monumental de Barcelona.[31][56] It would not affect the correbous, a traditional game of the Ebro where lit flares are attached to a bull’s horns. The ‘correbous’ however is only seen in the municipalities in the south of Tarragona, and is essentially Catalan.[57]

See also

- Arenas:

- People:

- List of bullfighters

- Ordóñez (bullfighter family)

- Romero dynasty

- CAS International, Committee against bullfighting

- Animals:

- Andalusian horse

- Fighting Cattle, bull breed used for fighting

- Iberian horse

- Lusitano, horse breed used in bullfighting

- Miura, a bull breed

- Styles of bullfighting:

- Picador and rejoneador, two Spanish styles of horse mounted bullfighting

- Cow fighting, Swiss style pitting cows against each other

- Running of the Bulls, running event usually in the morning of the bullfight

- Jallikattu, unarmed bull-taming in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu

- Tōgyū, bullfighting style of the Ryukyu Islands (particularly Okinawa) in Japan)

- Literature and films:

- The opera Carmen features a toreador as a major character, a well-known song about him, and a bullfight off-stage at the climax.

- Llanto por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías ("Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías", 1935), a poem by Federico García Lorca.[58]

- The Dangerous Summer, Ernest Hemingway's chronicle of the bullfighting rivalry between Luis Miguel Dominguín and his brother-in-law Antonio Ordóñez

- Death in the Afternoon, Ernest Hemingway's treatise on Spanish bullfighting (OCLC 704339)

- "The Sun Also Rises", a novel by Ernest Hemingway, includes many accounts of bullfighting.

- Shadow of a Bull, book by Maia Wojciechowska about a bullfighter's son, Manolo Olivar

- The Story Of A Matador, David L. Wolper's 1962 documentary about the life of the matador Jaime Bravo

- Around the World in Eighty Days included scenes of Cantinflas bullfighting in Chinchón.

- Talk to Her, film by Pedro Almodóvar, contains subplot concerning female matador who is gored during a bullfight. The director was criticized for shooting footage of a bull being actually killed during a bullfight staged especially for the film.

- The Bullfighter And The Lady, about an expat American training as a matador.

- Others

- Ban on bullfighting in Catalonia

- Paso Doble

References

- ^ ταυρομαχία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ http://www.cas-international.org/es/home/sufrimiento-de-toros-y-caballos/corridas-de-toros/corridas-de-toros-en-latinoamerica/

- ^ on-line descriptions in English – most available references are in Swahili Photos of Pemba bullfight on Flickr

- ^ "www.worldstadiums.com". www.worldstadiums.com. http://www.worldstadiums.com/north_america/countries/mexico/central_mexico.shtml. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ http://www.realmaestranza.com/PAGINASR/historiapt.htm

- ^ Guillaume ROUSSEL. "Pierre tombale de Clunia – 4473 – L'encyclopédie – L'Arbre Celtique". Arbre-celtique.com. http://www.arbre-celtique.com/encyclopedie/pierre-tombale-de-clunia-4473.htm. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Toro de Lidia (15 November 2006). "Toro de Lidia – Toro de lidia". Cetnotorolidia.es. http://www.cetnotorolidia.es/opencms_wf/opencms/toro_de_lidia/origen_e_historia/index.html. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Royal Decree 145/1996, of 2 February, to modify and reword the Regulations of Taurine Spectacles

- ^ "Bullfighting." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 14 Jan. 2009

- ^ "Longhorn_Information – handling". ITLA. http://www.itla.net/index.cfm?sec=Longhorn_Information&con=handling. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ http://iacuc.tennessee.edu/pdf/Policies-AnimalCare/Cattle-BasicCare.pdf

- ^ Isaacson, Andy, (2007), "California's 'bloodless bullfights' keep Portuguese tradition alive", San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Vaches Pour Cash: L'Economie de L'Encierro Provençale, Dr. Yves O'Malley, Nanterre University 1987.

- ^ http://www.mangalorean.com/browsearticles.php?arttype=Feature&articleid=284

- ^ Bullfighting Spactacles: State Norms (in Spanish) Example: Los espectáculos cómico-taurinos no podrán celebrarse conjuntamente con otros festejos taurinos en los que se dé muerte a las reses.

- ^ "Spanish bull fighter suffers horrific injury as bulls horn enters beneath the chin and comes out of mouth". 24 May 2010. http://www.nationalturk.com/en/bullfight-injury-as-matador-gored-through-chin-in-madrid-spain-56646415. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Laborde, Christian (2009). Corrida, Basta!. Paris, France: Editions Robert Laffont. pp. 14–15, 17–19, 38, 40–42, 52–53.

- ^ See Id. at 17-18.

- ^ "Encuesta Gallup: Interés por las corridas de toros (In Spanish)". Columbia.edu. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/spanish/cultura/texts/Gallup_CorridasToros_0702.htm. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Most hated sports: Going to the dogs". nbcsports.msnbc.com. 28 September 2003. http://nbcsports.msnbc.com/id/3087763/. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "What is bullfighting?". http://www.league.org.uk/content.asp?CategoryID=1938.

- ^ "Running of the Bulls Factsheet". http://www.runningofthenudes.com/bullfighting_facts.asp.

- ^ "ICABS calls on Vodafone to drop bullfighting from ad". http://www.banbloodsports.com/ln-0807c.htm.

- ^ "The suffering of bullfighting bulls". http://english.stieren.net/index.php?id=390.

- ^ The Bulletpoint Bullfight, p. 6, ISBN 978-1-4116-7400-4

- ^ No permitas que tus impuestos financien la tortura a los toros: ¡Actúa ya. AnimaNaturalis (Spanish)

- ^ Parte de nuestros impuestos se dedican a financiar estas prácticas. Cada gallego aporta 42 euros al año a la tauromaquia 21 July 2008. El Progreso (Spanish)

- ^ Los alcaldes antitaurinos cierran el grifo a las corridas Público (Spanish)

- ^ "For a Bullfighting-free europe". Bullfightingfreeeurope.org. http://www.bullfightingfreeeurope.org/. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Bullfighting ban and the horns of a dilemma for Spain". 28 July 2010. http://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/features/Bullfighting-ban-and-the-horns.6445725.jp. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "Catalonia bans bullfighting in landmark Spain vote". British Broadcasting Corporation. 28 July 2010. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-10784611. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ "Queen Sofia of Spain – Phantis". Wiki.phantis.com. 2 July 2006. http://wiki.phantis.com/index.php/Queen_Sofia_of_Spain. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Casa de Su Majestad el Rey de España". Casareal.es. 22 May 2007. http://www.casareal.es/noticias/news/20070522_Corrida_Toros_Prensa-ides-idweb.html. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ gerrit schimmelpeninck. "Casa Real". Portaltaurino.com. http://www.portaltaurino.com/corazon/casa_real.htm. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Plaza de Toros de Las Ventas". Las-ventas.com. http://www.las-ventas.com/cronicas2005/0608/portada.htm. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Plaza de Toros de Las Ventas". Asp.las-ventas.com. http://asp.las-ventas.com/noticias/noticia_detalle.asp?codigo=1126&codigo_seccion=7. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "www.spanish-fiestas.com". http://www.spanish-fiestas.com/bullfighting/.

- ^ "Milhamoth Shewarim" (Hebrew), "Halacha Yomit," 17 October 2010, accessed 26 December 2010.

- ^ Shehada, Housni al-Khateeb (25 March 2009). "The attitude towards animals in Islam according to Islamic rulings on the internet". Ynetnews. http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3688401,00.html. Retrieved 20 May 2011. "In the majority of replies, the jurists refer to the explicit prohibition on the torturing of animals for purposes of amusement, entertainment or sport intended for spectator pleasure (e.g., bullfighting in Spain)."

- ^ No more 'ole'? Matadors miffed as Spain removes bullfighting from state TV

- ^ TVE explains the decision not to broadcast bullfighting is a financial one[dead link]

- ^ AFP/ (22 August 2007). "Las corridas de toros corren peligro en TVE – Nacional – Nacional". Abc.es. http://www.abc.es/hemeroteca/historico-22-08-2007/abc/Nacional/las-corridas-de-toros-corren-peligro-en-tve-_164480243859.html. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ ASANDA. "¡PROHÍBEN CORRIDAS DE TOROS PARA NIÑOS! (EN COSTA RICA) :: ASANDA :: Asociación Andaluza para la Defensa de los Animales". ASANDA. http://www.asanda.org/index.php?name=News&file=article&sid=646. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Landmark bullfighting ban". News24.com. 3 March 2009. http://www.news24.com/News24/World/News/0,,2-10-1462_2479298,00.html. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Veronica Cerrato. "Desde 1899, Argentina sin Corridas de Toros //". Animanaturalis.org. http://www.animanaturalis.org/p/883. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Bloodless bullfights animate California's San Joaquin Valley". The Los Angeles Times. 26 July 2007. http://travel.latimes.com/articles/la-trw-californiabullfighting29jul29.

- ^ "Canary Islands Government. Law 8/1991, dated April the 30th, for animal protection (Spanish)". Gobiernodecanarias.org. 13 May 1991. http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/boc/1991/062/001.html. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "La prohibición de la tauromaquia: un capítulo del antiespañolismo catalán". El Mundo. 29 July 2010. http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2010/07/28/toros/1280350886.html. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ "Los toros no están prohibidos en Canarias". Mundotoro. 30 July 2010. http://www.mundotoro.com/noticia/los-toros-no-estan-prohibidos-en-canarias/79708. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ Fiona Govan, "Bullfighting's Future in Doubt," The Telegraph 20 Dec. 2006.

- ^ "Las corridas de toros irán a referendum" by El Comercio

- ^ "Correa anuncia consulta popular sobre corridas de toros" by El Telegrafo

- ^ "Correa anuncia consulta popular sobre seguridad, justicia y corridas de toros" by El Universo

- ^ http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/world/2011/0509/1224296491068.html

- ^ "Llum verda a la supressió de les corrides de toros a Catalunya". Avui.cat. 18 December 2009. http://www.avui.cat/cat/notices/2009/12/llum_verda_a_la_supressio_de_les_corrides_de_toros_a_catalunya_81775.php. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Raphael Minder (28 July 2010). "Spanish Region Bans Bullfighting". nytimes.com. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/29/world/europe/29spain.html?ref=world. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ http://www.typicallyspanish.com/news/publish/article_27265.shtml#ixzz10NKQxwpk

- ^ "Lorca's poem in English". Oldpoetry.com. http://oldpoetry.com/opoem/15295-Federico-Garcia-Lorca-Lament-For-Ignacio-Sanchez-Mejias. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

Further reading

- Hemingway, Ernest (1932) Death in the Afternoon

- Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier. Bullfighting: A Troubled History (U. of Chicago Press, 2010); 206 pages, ISBN 9781861895189

- Ciofalo, John J. "The Artist in the Vicinity of Death." The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Shadow of a Bull, book by Maia Wojciechowska about a bullfighter's son

- Ogorzaly, Michael A, When Bulls Cry: The Case Against Bullfighting, 2006, AuthorHouse, ISBN 1-4259-2772-6

- Wood, Tristan, "How To Watch A Bullfight", 2011, Merlin Unwin Books, ISBN 9781906122270

- Fiske-Harrison, Alexander, "Into The Arena: The World of the Spanish Bullfight", 2011, Profile Books, ISBN 1846683351

- Marvin, Garry, "Bullfight", 1988, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 9780252064371

Women Writers on Bullfighting, Women Matadors

- Pink, Sarah, "Women & Bull Fighting", 1997, Berg Publishers, ISBN 185973961X

- Poon, Wena, "Alex y Robert", Salt Publishing, London, 2010. ISBN 9781907773082. Novel about an American teenage girl training as a matador in contemporary Spain. Also a BBC Radio 4 series.

- Kennedy, Alison L., "On Bullfighting", 2001, Anchor Books, ISBN 0385720815

External links

- "Bullfighting 101" - user-friendly explanations of what you are seeing at a typical bullfight

- Bullfighting: Culture & Controversy – slideshow by Life magazine

- Bullfighting in Barcelona - slideshow by The First Post

- Israel Lancho, Spanish Bullfighter Gored, The Huffington Post, 29 May 2009

- "Arena" 2011 film about contemporary Spanish bullfighting and matador schools by Austrian director Gunter Schwaiger

- Supporting bullfighting

- Faq

- Story of a matador (1962), produced by David L. Wolper

- "50 Reasons Defending Bullfighting"

- "End bullfighting and you give in to neutering forces of accepted taste"

- "Bullfighting banned in Catalonia but more popular than ever in France"

- "Opinion y Toros"

- "Burladero"

- "Canal+ Toros"

- "6 Toros 6"

- Against bullfighting

- Complete dossier about bullfighting (spanish)

- CAS International (Comité Anti Stierenvechten)

- International Movement Against Bullfight (IMAB)

- Federation of Anti-Bullfighting Societies (FLAC)

- League Against Cruel Sports

- Partido Antitaurino Contra el Maltrato Animal – Anti-bullfighting party against animal abuse

- Movimento Anti-Touradas de Portugal

Categories:- Blood sports

- Bullfighting

- Animal killing

- Animal cruelty

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.