- Northern Epirus

-

- Note: For the autonomous state formed in the region at 1914, see: Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus.

The region of Epirus, stretching across Greece and Albania. - Legend

- grey: Approximate extent of Epirus in antiquity

- orange: Greek periphery of Epirus

- green: Approximate extent of largest concentration of Greeks in "Northern Epirus", early 20th cent.[1]

- red dotted line: Territory of Northern Epirus

Northern Epirus (Greek: Βόρειος Ήπειρος, Vorios Ipiros, Albanian: Epiri i Veriut) is a term used to refer to those parts of the historical region of Epirus, in the western Balkans, that are part of the modern Albania. The term is used mostly by Greeks and is associated with the existence of a substantial ethnic Greek population in the region. It also has connotations with political claims on the territory on the grounds that it was held by Greece and in 1914 was declared an independent state[2] by the local Greeks against annexation to the newly founded Albanian principality.[3] The term is typically rejected by most Albanians for its irredentist associations.

The term "Northern Epirus" started to be used by Greeks in 1913, upon the creation of the Albanian State following the Balkan Wars, and the incorporation into the latter of territory that was regarded by many Greeks as geographically, historically, culturally, and ethnologically connected to the Greek region of Epirus since antiquity.[4] In the spring of 1914, the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was proclaimed by ethnic Greeks in the territory and recognized by the Albanian government, though it proved short-lived as Albania collapsed with the onset of World War I. Greece held the area between 1914 and 1916, and unsuccessfully tried to annex it in March 1916,[4] however in 1917 it was driven from the area by Italy, who took over most of Albania.[5] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece, however the area reverted to Albanian control in November 1921, following Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War.[6] During the interwar period, tensions remained high due to the educational issues surrounding the Greek minority in Albania.[4] Following Italy's invasion of Greece from the territory of Albania in 1940 and the successful Greek counterattack, the Greek army briefly held Northern Epirus for a six month period until the German invasion of Greece in 1941.

Tensions remained high during the Cold War, as the Greek minority was subjected to repressive measures (along with the rest of the country's population). Although a Greek minority was recognized by the Hoxha regime, this recognition only applied to an "official minority zone" consisting of 99 villages, leaving out important areas of Greek settlement, such as Himara. People outside the official minority zone received no education in the Greek language, which was prohibited in public. The Hoxha regime also diluted the ethnic demographics of the region by relocating Greeks living there and settling in their stead Albanians from other parts of the country.[4] Relations began to improve in the 1980s with Greece's abandonment of any territorial claims over Northern Epirus and the lifting of the official state of war between the two countries.[4] In the post-Cold War era relations have continued to improve though tensions remain over the availability of education in the Greek language outside the official minority zone, property rights, and occasional violent incidents targeting members of the Greek minority.

Geography

The term Epirus is used both in the Albanian and Greek language, but in Albanian refers only to the historical and not modern region.

In antiquity, the northern border of the historical region of Epirus (and of the ancient Greek world) was the Gulf of Oricum,[7][8] or alternatively, the mouth of the Aoös river, immediately to the north of the Bay of Aulon (modern-day Vlore.[9] To the south, classical Epirus ended at the Ambracian Gulf, while to the east it was separated from Macedonia and Thessaly by the Pindus mountains. The island of Corfu is situated off the coast of Epirus but is not regarded as part of it.

Rather than a clearly defined geographical term, "Northern Epirus" is largely a political and diplomatic term applied to those areas partly populated by ethnic Greeks that were incorporated into the newly-independent Albanian state in 1913.[4] According to the 20th century definition, Northern Epirus stretches from the Ceraunian mountains north of Himara southward to the Greek border, and from the Ionian coast to Lake Prespa. The region defined as Northern Epirus thus stretches further east than classical Epirus, and includes parts of the historical region Macedonia. Northern Epirus is rugged, characterized by steep limestone ridges that parallel the Ionian coast, with deep valleys between them.[10] The main rivers of the area are: Vjosë/Aoos (Greek: Αώος, Aoos) its tributary the Drino (Greek: Δρίνος, Drinos), the Osum (Greek: Άψος Apsos) and the Devoll (Greek: Εορδαϊκός Eordaikos). Some of the cities and towns of the region are: Himarë, Sarandë, Delvinë, Gjirokastër, Tepelenë, Përmet, Leskovik, Ersekë, Korçë, Bilisht and the once prosperous town of Moscopole.

History

Main article: Epirus (region)Mythological foundations and ancient settlements

Many of the region’s settlements are associated with the Trojan Epic cycle. Elpenor from Ithaca, in charge of Locrians and Abantes from Evia, founded the cities of Orikum and Thronium on the Bay of Aulon. Amantia was believed to have been founded by Abantes from Thronium. Neoptolemos of the Aeacid dynasty, in charge of Myrmidones, founded a settlement which in classical antiquity would become known as Bylliace (near Apollonia). Aeneas and Helenus were believed to have founded Bouthroton (modern-day Butrint). Moreover, a son of Helenus named Chaon was believed to be the ancestral leader of the Chaonians.[7]

Prehistory and Ancient period

The first arrival of Greek speaking tribes in the region of Epirus may date around 2100 B.C., at the same period they took control of the area of lake Malik. During the Middle Helladic period (1900-1600 B.C.) these tribes took possession of northern Epirus and created two entities.[11]

The earliest recorded inhabitants of the region (c. 7th century BC) were the Chaonians, one of the main Greek tribes of ancient Epirus, and the region was known as Chaonia. During the 7th century B.C. Chaonian rule was dominant over the region and their power stretched from the Ionian coast to the region of Korçë in the east. Important Chaonian settlements in the area included their capital Phoenice, the ports of Onchesmos and Chimaera (modern-day Saranda and Himara, respectively), and the port of Bouthroton (modern-day Butrint. Tumulus II in Kuc i Zi near modern Korçë is to date to that age (ca. 650 B.C.) and it is claimed that it belonged to Chaonian nobles.[7] The strength of the Chaonians prevented other Greeks from establishing colonies on the Chaonian shore, however, several colonies were established in the 8th-6th centuries BC immediately to the north of the Ceraunian mountains, the northern limit of Chaonian territory.[12] These include Aulon (modern-day Vlorë), Apollonia, Epidamnus (modern-day Durres, Oricum, Thronion, and Amantia.

In 330 BC, the tribes of Epirus were united into a single kingdom under the Aeacid ruler Alcetas II of the Molossians, and in 232 B.C. the Epirotes established the "Epirotic League" (Greek: Κοινόν Ηπειρωτών), with Phoenice as one of its centers. The unified state of Epirus was a significant power in the Greek world until the Roman conquest in 167 BC.[13]

Roman and Byzantine period

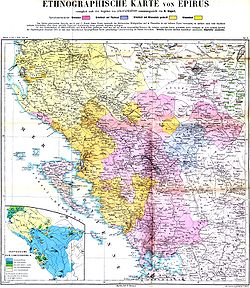

Ethnographic map of the Epirus region, 1878. Pink - Greek speakers, Blue - Greek and Vlach (Aromanian) speakers, Orange - Greek and Albanian speakers, Yellow - Albanian speakers

Christianity first spread in Epirus during the 1st century AD, but did not prevail until the 4th century. The presence of local bishops in the Ecumenical Synods (already from 381 A.D.) proves that the new religion was well organized and already widely spread inside the Greek world of the Roman and post-Roman period.[14]

In Roman times, the ancient Greek region of Epirus became the province of Epirus vetus ("Old Epirus"), while a new province Epirus Nova ("Epirus Nova") was formed out of parts of[15] Illyria that had become partly Hellenic[16] or partly Hellenized.[16] The line of division between Epirus Nova and the province of Illyricum was the Drin River in modern northern Albania.[17] This line of division also corresponds with the Jirecek line, which divides the Balkans into those areas under Hellenic influence in antiquity, and those under Latin influence.

When the Roman Empire split into East and West, Epirus became part of the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire; the region witnessed the invasions of several nations: Visigoths, Avars, Slavs, Serbs, Normans, and various Italian city-states and dynasties (14th century). However the region’s culture remained closely tied to the centers of the Greek world, and retained its Greek character through the medieval period.

In 1204, the region was part of the Despotate of Epirus, a successor state of the Byzantine Empire. Despot Michael I found there strong Greek support in order to facilitate his claims for the Empire’s revival. In 1281, a strong Sicilian force that planned to conquer Constantinople was repelled in Berat after a series of combined operations by local Epirotes and Byzantine troops. In 1345, the region was ruled by the Serbs of Stefan Dušan. However, the Serbian rulers retained much of the Byzantine tradition and used Byzantine titles to secure the loyalty of the local population. At the same time Venetians controlled various ports of strategic importance, like Vouthroton, but the Ottoman presence became more and more intense until finally in the middle of the 15th century, the entire area came under Turkish rule.

Ottoman period

Following the Ottoman conquest, local authorities were exclusively Muslim, ethnically either Albanian or Turkish. However, there were specific parts of Epirus that enjoyed local autonomy, such as Himarë, Droviani, or Moscopole. In spite of the Ottoman presence, Christianity prevailed in many areas and became an important reason for preserving the Greek language, which was also the language of trade.[18] According to the Ottoma "Millet" system, religion was the main identifier of ethnicity, and thus all Orthodox Christians (including Aromanians and Orthodox Albanians) were classified as "Greeks", while all Muslims (including Muslim Albanians) were considered "Turks". This view would continue to influence Greek perceptions of the territory for much of the 20th century.[4]

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, inhabitants of the region participated in the Greek Enlightenment. One of the leading figures of that period, the Orthodox missionary Cosmas of Aetolia, traveled and preached extensively in northern Epirus, founding the Acroceraunian school in Himara in 1770. It is believed that he founded more than 200 Greek schools until his execution by Turkish authorities near Berat.[19] In addition, the first printing press in the Balkans, after that of Constantinople, was founded in Moscopole (nicknamed "New Athens") by a local Greek.[20] From the mid-18th century trade in the region was thriving and a great number of educational facilities and institutions were founded throughout the rural regions and the major urban centers as benefactions by several Epirot entrepreneurs.[21] In Korce a special community fund was established that aimed at the fundation of Greek cultural institutions.[22]

During this period a number of uprisings against the Ottoman empire periodically broke out. In the Orlov Revolt (1770) several units of Riziotes, Chormovites and Himariotes supported the armed operation. Northern Epirus took also part in the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830): many locals revolted, organized armed groups and joined the revolution.[23] The most distinguished personalities were the engineer Konstantinos Lagoumitzis[24] from Hormovo and Michail Spyromilios from Himarë. The latter was one of the most active generals of the revolutionaries and participated in several major armed conflicts, such as the Third Siege of Missolonghi, where Lagoumitzis was the defenders' chief engineer. M. Spyromilios also became a prominent political figure after the creation of the modern Greek state and discreetly supported the revolt of his compatriots in Ottoman-occupied Epirus in 1854, during the Crimean War.[25] Another uprising in 1878, in the Saranda-Delvina region, with the revolutionaries demanding union with Greece, was suppressed by the Ottoman forces, while in 1881, the Treaty of Berlin awarded to Greece the southernmost parts of Epirus.

Balkan Wars (1912-1913)

Picture of the official declaration of Northern Epirote Independence in Gjirokastër (1 March 1914).

Picture of the official declaration of Northern Epirote Independence in Gjirokastër (1 March 1914).

With the outbreak of the First Balkan War (1912–1913) and the Ottoman defeat, the Greek army entered the region. The outcome of the following Peace Treaties of London[26] and of Bucharest,[27] signed at the end of the Second Balkan War, was unpopular among both Greeks and Albanians, as settlements of the two people existed on both sides of the border: Northern Epirus, already under the control of the Greek army, was awarded to the newly found Albanian State, while the southern part was ceded to Greece.

Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus (1914)

Main article: Autonomous Republic of Northern EpirusIn accordance with the wishes of the local Greek population, the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, centered in Gjirokastër on account of the latter's large Greek population,[28] was declared in March 1914 by the pro-Greek party, which was in power in southern Albania at that time.[29] Georgios Christakis-Zografos, a distinguished Greek politician from Lunxhëri, took the initiative and became the head of the Republic. In May, autonomy was confirmed with the Protocol of Corfu, signed by Albanian and Northern Epiroterepresentatives and approved by the Great Powers. The signing of the Protocol ensured that the region would have its own administration, recognized the rights of the local Greeks and provided self government under nominal Albanian sovereignty.[29]

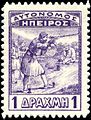

However, the agreement was never fully implemented, because when World War I broke out in July, Albania collapsed. Although short-lived,[29][30] the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus left behind a substantial historical record, such as its own postage stamps.

World War I and following peace treaties (1914-1921)

Under an October 1914 agreement among the Allies,[31] Greek forces re-entered Northern Epirus and the Italians seized the Vlore region.[29] Greece officially annexed Northern Epirus in March 1916, but was forced to revoke by the Great Powers.[4] During the war the French Army occupied the area around Korçë in 1916, and established the Republic of Korçë. In 1917 Greece lost control of the rest of Northern Epirus to Italy, who by then had took over most of Albania.[5] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece after World War I, however, political developments such as the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-22 and, crucially, Italian, Austrian and German lobbying in favor of Albania resulted in the area being ceded to Albania in November 1921.[6]

Interwar period (1921-1939) - Zog's regime

The Albanian Government, with the country's entrance to the League of Nations (October 1921), made the commitment to respect the social, educational, religious rights of every minority.[32] Questions arose over the size of the Greek minority, with the Albanian government claiming 16,000, and the League of Nations estimating it at 35,000-40,000.[4] In the event, only a limited area in the Districts of Gjirokastër, Sarandë and four villages in Himarë region consisting of 15,000 inhabitants[33] was recognized as a Greek minority zone. The following years, measures were taken to suppress[34] the minority's education. The Albanian state viewed Greek education as a potential threat to its territorial integrity.[33] Greek schools were either closed or forcibly converted to Albanian schools and teachers were expelled from the country. The 360 schools of the pre-World War I period were reduced dramatically in the following years and education in Greek was finally eliminated altogether in 1935:[35][36]

1926: 78, 1927: 68, 1928: 66, 1929: 60, 1930: 63, 1931: 64, 1932: 43, 1933: 10, 1934: 0

With the intervention of the League of Nations in 1935, a limited number of schools, and only of those inside the officially recognized zone, were reopened.

During this period, the Albanian state led efforts to establish an independent orthodox church (contrary to the Protocol of Corfu), thereby reducing the influence of Greek language in the country's south. According to a 1923 law, priests who were not Albanian speakers, as well as not of Albanian origin, were excluded from this new autocephalous church.[33]

World War II (1939-1945)

Main articles: Greek-Italian War and Northern Epirus Liberation FrontIn 1939, Albania became an Italian protectorate and was used to facilitate military operations against Greece the following year. The Italian attack, launched at October 28, 1940 was quickly repelled by the Greek forces. The Greek army, although facing a numerically and technologically superior army, counterattacked and in the next month managed to enter Northern Epirus. Northern Epirus thus became the site of the first clear setback for the Axis powers. However, after a six month period of Greek administration, the invasion of Greece by Nazi Germany followed in April 1941 and Greece capitulated.

Following Greece's surrender, Northern Epirus again became part of the Italian-occupied Albanian protectorate. Many Northern Epirotes formed resistance groups and organizations in the struggle against the occupation forces. In 1942 the Northern Epirote Liberation Organization (EAOVI, also called MAVI) was formed.[37] Some others joined the left-wing Albanian National Liberation Army, in which they formed a separate battalion (named Thanasis Zikos).[38]

During October 1943-April 1944, the Albanian collaborationist organization Balli Kombëtar with support of Nazi German officers mounted a major offensive in Northern Epirus and fierce fighting occurred between them and the EAOVI. The results were devastating. During this period over 200 Greek populated towns and villages were burned or destroyed, 2,000 Northern Epirotes were killed, 5,000 imprisoned and 2,000 taken hostages to concentration camps. Moreover, 15,000 homes, schools and churches were destroyed. Thirty thousand people had to find refuge in Greece during and after that period, leaving their homeland.[39][40] When the war ended, a United States Senate resolution demanded the cession of the region to the Greek state, but according to the following post war international peace treaties it remained part of the Albanian state.[41]

Cold War period (1945-1991) - Hoxha's regime

General violations of human and minority rights

After World War II, Albania was governed by a Communist regime led by Enver Hoxha, which suppressed the minority (along with the rest of the population) and took measures to disperse it or at least keep it loyal to Albania.[42] Pupils were taught only Albanian history and culture at primary level, the minority zone was reduced from 103 to 99 villages (excluding Himarë), many Greeks were forcibly removed from the minority zones to other parts of the country, thereby losing their fundamental minority rights (as a product of communist population policy, an important and constant element of which was to pre-empt ethnic sources of political dissent). Greek place-names were changed to Albanian ones, and Greeks were forced to change their personal names into Albanian names.[43] Archeological sites of the Ancient Greek and Roman era were also presented as "Illyrian" by the state.[44] The use of the Greek language, prohibited everywhere outside the minority zones, was prohibited for many official purposes within them as well.[18][45][46] As a result of these policies, relations with Greece remained extremely tense throughout most of the Cold War.[4] On the other hand, Enver Hoxha favored a few specific members of the minority, offering them prominent positions within the country's system, as part of his "tokenism" policy. However, when the Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev asked about giving more rights to the minority, even autonomy, the answer was negative.[38]

Censorship

Strict censorship was introduced in Socialist Albania as early as 1944,[47] while the press remained under tight dictatorial control right up until the end of the Eastern Bloc (1991).[48] In 1945, Laiko Vima, a propaganda organ of the Party of Labour of Albania, was the only printed media that was allowed to be published in Greek and was accessible only within Gjirokastër District.[49]

Resettlement policy

Although the Greek minority had some limited rights, during that period a number of Muslim Cham Albanians, that were expelled from Greece after World War II, were given new homes in the area, diluting the local Greek element.[50] Moreover, during this period a number of new settlements, consisting of Muslim settlers, were created as a buffer zone between the recognized 'minority zone' and regions of unclear ethnic consciousness.[35]

Isolation and labour camps

Stalinist Albania, already increasingly paranoid and isolated after de-Stalinization and the death of Mao Tse Tung (1976),[51] restricted visitors to 6,000 per year, and segregated those few that traveled to Albania.[52] The country was virtually isolated and common penalties for attempts to escape the country, for ethnic Greeks, were execution for the offenders and exile for their families, usually in mining camps in central and northern Albania.[53] The regime maintained twenty-nine prisons and labour camps throughout Albania, that were filled with more than 30,000 "enemies of the state" year after year. It was unofficially reported that a large percentage of the imprisoned were ethnic Greeks.[54]

Prohibition of religion

The state attempted to suppress any religious practice (both public and private), adherence to which was considered "anti-modern" and dangerous to the unity of the Albanian state. The process started in 1949,[35] with the confiscation and nationalization of Orthodox Church property and intensified in 1967 when the authorities conducted a violent campaign to extinguish[55] all religious life in Albania, claiming that it had divided the Albanian nation and kept it mired in backwardness. Student agitators combed the countryside, likewise forcing Albanians and Greeks to quit practicing their faith. All churches, mosques, monasteries and other religious institutions were closed or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, and workshops. Clergy were imprisoned, and owning an icon became an offense that could be prosecuted under Albanian law. The campaign culminated in an announcement that Albania had become the world's first atheistic state, a feat touted as one of Enver Hoxha's greatest achievements.[56] Christians were prohibited from mentioning Orthodoxy even in their own homes, visit their parents’ graves, light memorial candles or make the sign of the Cross. In this respect, the campaign against religions hit ethnic Greeks disproportionately, since affiliation to the Eastern Orthodox rite has traditionally been a strong component of Greek identity.[57]

1980s thaw

The first serious attempt to improve relations was initiated by Greece in the 1980s, during the government of Andreas Papandreou.[4] In 1984, during a speech in Epirus, Papandreou declared that the inviolability of European borders as stipulated in the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, to which Greece was a signatory, applied to the Greek-Albanian border.[4] The most significant change occurred on 28 August 1987, when the Greek Cabinet lifted the state of war that had been declared since November 1940.[4] At the same time, Papandreou deplored the "miserable condition under which the Greeks in Albania live".[4]

Post-communist period (1991-present)

Beginning in 1990, large number of Albanian citizens, including members of the Greek minority, began seeking refuge in Greece. This exodus turned into a flood by 1991, creating a new reality in Greek-Albanian relations.[4] With the fall of communism in 1991, Orthodox churches were reopened and religious practices were permitted after 35 years of strict prohibition. Moreover, Greek-language education was initially expanded. In 1991 ethnic Greeks shops in the town of Saranda were attacked, and inter-ethnic relations throughout Albania worsened.[38][58] Greek-Albanian tensions escalated in November 1993 when seven Greek schools were forcibly closed by the Albanian police.[59] A purge of ethnic Greeks in the professions in Albania continued in 1994, with particular emphasis in law and the military.[60] On 10 April 1994, Albania announced that two of its soldiers had been killed in an attack on a military camp in Peshkepi, close to the Greek border. The attack was claimed by the Northern Epirus Liberation Front (MAVI), which had officially disbanded at the end of World War II.

Trial of the Omonoia Five

Tensions increased when on 20 May 1994 the Albanian Government took into custody five members of the ethnic Greek advocacy organization Omonoia on the charge of high treason, accusing them of secessionist activities and illegal possession of weapons (a sixth member was added later).[61] Sentences of six to eight years were handed down. The accusations, the manner in which the trial was conducted and its outcome were strongly criticized by Greece as well as international organizations. Greece responded by freezing all EU aid to Albania, sealing its border with Albania, and between August–November 1994, expelling over 115,000 illegal Albanian immigrants, a figure quoted in the US Department of State Human Rights Report and given to the American authorities by their Greek counterpart.[62] Tensions increased even further when the Albanian government drafted a law requiring the head of the Orthodox Church in Albania be born in Albania, which would force the then head of the church, the Greek Archbishop Anastasios of Albania from his post.[4] In December 1994, however, Greece began to permit limited EU aid to Albania as a gesture of goodwill, while Albania released two of the Omonoia defendants and reduced the sentences of the remaining four. In 1995, the remaining defendants were released on suspended sentences.[4]

Recent years

In recent years relations have significantly improved; Greece and Albania signed a Friendship, Cooperation, Good Neighborliness and Security Agreement on March 21, 1996.[4] Additionally, Greece is Albania's main foreign investor, having invested more than 400 million dollars in Albania, Albania's second largest trading partner, with Greek products accounting for some 21% of Albanian imports, and 12% of Albanian exports coming to Greece, and Albania's fourth largest donor country, having provided aid amounting to 73.8 million euros.[63]

Although relations between Albania and Greece have greatly improved in recent years, the Greek minority in Albania continues to suffer discrimination particularly regarding education in the Greek language,[4] property rights of the minority, and violent incidents against the minority by nationalist extremists. Tensions resurfaced during local government elections in Himara in 2000, when a number of incidents of hostility towards the Greek minority took place, as well as with the defacing of signposts written in Greek in the country's south by Albanian nationalist elements,[64] and more recently following the death of Aristotelis Goumas. According to diplomatic sources, there has recently been an upsurge in nationalist activity among Albanians targeting the Greek minority, especially following the ruling of the International Court of Justice in favor of Kosovo's independence.[65]

Demographics

Main article: Greeks in AlbaniaIn Albania, Greeks are considered a "national minority". There are no reliable[46] statistics on the size of any ethnic minorities in Albania, as the Albanian government does not include them on the census. The Albanian government is not going to conduct an official census on ethnicity. Some commentators allege that this is out of fear that a considerable part of the population will register themselves as Greek.[66]

According to data presented to the 1919 Paris Conference, by the Greek side, the Greek minority numbered 120,000,[67] and the last census to include data on ethnic minorities conducted in 1989 under the communist regime cites only 58,785 Greeks although the total population of Albania had tripled in the meantime.[67] More recent estimations by the Albanian government raise the number to 80,000.[68]

However, the area studied was confined to the southern border, and this estimate is considered to be low. Under this definition, minority status was limited to those who lived in 99 villages in the southern border areas, thereby excluding important concentrations of Greek settlement and making the minority seem smaller than it is.[46] Sources from the Greek minority have claimed that there are up to 400,000 Greeks in Albania, or 12% of the total population at the time (from the "Epirot lobby" of Greeks with family roots in Albania).[69] Most western estimates of the minority's size put it at around 200,000, or ~6% of the population,[70] though a large number, possibly two thirds, has migrated to Greece in recent years.[4]

The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization estimates the Greek minority at approximately 70,000 people.[71] Other independent sources estimate that the number of Greeks in Northern Epirus is 117,000 (about 3.5% of the total population),[72] a figure close to the estimate provided by The World Factbook (2006) (about 3%). But this number was 8% by the same agency a year before.[73][74] A 2003 survey conducted by Greek scholars estimate the size of the Greek minority at around 60.000.[75] The total population of Northern Epirus is estimated to be around 577,000 (2002), with main ethnic groups being Albanians, Greeks and Vlachs.[76]

The Northern Epirote issue at present

—From the Protocol of Corfu, signed by Epirote and Albanian delegates, May 17, 1914:

The Orthodox Christian communities are recognized as juridical persons, like the others. They will enjoy the possessions of property and be free to dispose of it as they please. The ancient rights and hierarchical organization of the said communities shall not be impaired except under agreement between the Albanian Government and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Education shall be free. In the schools of the Orthodox communities the instruction shall be in Greek. In the three elementary classes Albanian will be taught concurrently with Greek. Nevertheless, religious education shall be exclusively in Greek.

Liberty of language:The permission to use both Albanian and Greek shall be assured, before all authorities, including the Courts, as well as the elective councils.

These provisions will not only be applied in that part of the province of Corytza now occupied militaritly by Albania, but also in the other southern regions.[77]While violent incidents have declined in recent years, the ethnic Greek minority has pursued grievances with the government regarding electoral zones, Greek-language education, property rights. On the other hand minority representatives complain of the government's unwillingness to recognize the possible existence of ethnic Greek towns outside communist-era 'minority zones'; to utilize Greek on official documents and on public signs in ethnic Greek areas; to ascertain the size of the ethnic Greek population; and to include more ethnic Greeks in public administration.[78] There have been many minor incidents between the Greek population and Albanian authorities over issues such as the alleged involvement of the Greek government in local politics, the raising of the Greek flag on Albanian territory, and the language taught in state schools of the region; however, these issues have, for the most part, been non-violent.

'Minority zone'

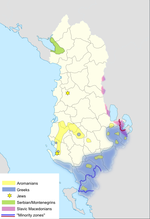

Approximate extent of the recognized (after 1945) Greek 'minority zone' in green, according to the 1989 Albanian census. Greek majority areas in green.[79]

Approximate extent of the recognized (after 1945) Greek 'minority zone' in green, according to the 1989 Albanian census. Greek majority areas in green.[79]

The Albanian Government continues to use the term "minority zones", in violation to human rights issues, to describe the southern districts consisting of 99 towns and villages, which they have recognized majorities of ethnic Greeks. In fact it continues to contend that all those belonging to national minorities are recognised as such, irrespective of the geographical areas in which they live. However, the situation is somewhat different in practice. This results in a situation in which the protection of national minorities is subject to overly rigid geographical restrictions restricting access to minority rights outside these zones. One of the major fields that it has a practical application is that of education.[80][81]

Protests against irregularities in 2011 census

The census of October 2011 will include ethnicity for the first time in post-communist Albania, a long standing demand of the Greek minority and of international organizations.[82] However, Greek representatives already found this procedure unacceptable due to article 20 of the Census law, which was proposed by the nationalist oriented Party for Justice, Integration and Unity and accepted by the Albanian government. According to this, there is a $1,000 fine for someone who will declare anything other than what was written down on his birth certificate,[83] including certificates from the communist-era where minority status was limited to only 99 villages.[84][85] Indeed, Omonoia unanimously decided to boycott the census, since it violates the fundamental right of self determination.[86] Moreover, the Greek government called its Albanian counterpart for urgent action, since the right of free self-determination is not being guaranteed under these circumstances.[87]

Minority's representation on local and state politics

The minority's sociopolitical organization from promotion of Greek human rights, Omonoia, founded in January 1991, took an active role on minority issues. Omonoia was banned in the parliamentary elections of March 1991, because it violated the Albanian law which forbade 'formation of parties on a religious, ethnic and regional basis'. This situation resulted in a number of strong protests not only from the Greek side, but also from international organizations. Finally, on behalf of Omonoia, the Unity for Human Rights Party contested at the following elections, a party which represents that Greek minority in the Albanian parliament.[88]

In more recent years, tensions have surrounded the participation of candidates of the Unity for Human Rights Party in Albanian elections. In 2000, the Albanian municipal elections were criticised by international human rights groups for "serious irregularities" reported to have been directed against ethnic Greek candidates and parties.[89] The most recent municipal elections held in February 2007 saw the participation of a number of ethnic Greek candidates, with Vasilis Bolanos being re-elected mayor of the southern town of Himarë despite the governing and opposition Albanian parties fielding a combined candidate against him. Greek observers have expressed concern at the "non-conformity of procedure" in the conduct of the elections.[90]

In 2004, there were five ethnic Greek members in the Albanian Parliament, and two ministers in the Albanian cabinet.[91] Politicians from the Greek minority have also become MPs for other parties, as Spiro Ksera and Kosta Barka for DPA; and Anastas Angjeli, Vangjel Tavo for SPA.

Land distribution and property in post-communist Albania

The return to Albania of ethnic Greeks that were expelled during the past regime seemed possible after 1991. However, the return of their confiscated properties is even now impossible, due to Albanian's inability to compensate the present owners. Moreover, the full return of the Orthodox Church property also seems impossible for the same reasons.[59]

Education

Greek education in the region was thriving during the late Ottoman period (18th-19th centuries). When the First World War broke out in 1914, 360 Greek language schools were functioning in Northern Epirus (as well as in Elbasan, Berat, Tirana) with 23,000 students.[92] During the following decades the majority of Greek schools were closed and Greek education was prohibited in most districts. In the post-communist period (after 1991), the reopening of schools was one of the major objectives of the minority. In April 2005 a bilingual Greek-Albanian school in Korca,[93] and after many years of efforts, a private Greek school was opened in the Himara municipality in spring of 2006.[94]

Official positions

Albania

In Albanian bibliography it is widely claimed that the Greek minority as it currently exists was the result of population movements under the Ottoman empire, and the great majority of the Greeks arrived in modern Albania as indentured labourers in the time of the Ottoman beys denying any link with local ancient Greek presence.[95]

In 1994 the Albanian authorities admitted for the first time that Greek minority members exist not only in the designated 'minority zones' but all over Albania.[96]

Greece

In 1991, the Greek Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis specified that the issue, according the Greek minority in Albania, focuses on 6 major topics that the post-communist Albanian government should deal with[59]:

- The return of the confiscated property of the Orthodox Church and the freedom of religious practice.

- Functioning of Greek language schools (both public and private) in all the areas that Greek populations are concentrated.

- The Greek minority should be allowed to found cultural, religious, educational and social organizations.

- Illegal dismissals of members of the Greek minority from the country’s public sector should be stopped and same rights for admission should be granted (on every level) for every citizen.

- The Greek families that left Albania during the communist regime (1945–1991), should be encouraged to return to Albania and acquire their lost properties.

- The Albanian government should take the initiative to conduct a census on ethnological basis and give its citizens the right to choose without limitations their ethnicity.

Incidents

- In April 1994, Albania announced that unknown individuals attacked a military camp near the Greek-Albanian border (Peshkëpi incident), with two soldiers killed. Responsibility for the attack was taken by MAVI (Northern Epirus Liberation Front), which officially ceased to exist since the end of World War II. This incident triggered a serious crisis between Albanian-Greek relations.[96]

- The house of Himara's ethnic Greek mayor, Vasil Bollano, has been the target of a bomb attack twice, in 2004 and again in May 2010.[97]

- On August 12, 2010, ethnic tensions soared after ethnic Greek shopkeeper Aristotelis Goumas was killed when his motorcycle was hit by a car driven by three Albanian youths with whom Goumas allegedly had an altercation when they demanded that he not speak Greek to them in his store.[82][98] Outraged locals blocked the main highway between Vlore and Saranda and demanded reform and increased local Himariote representation in the local police force.[98] The incident was condemned by both the Greek and Albanian governments and three suspects are currently in custody awaiting trial.[98]

Gallery

See also

- Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

- Protocol of Corfu

- Albanisation

- Chameria

- Epirus (region)

- Northern Epirotes

- Postage stamps and postal history of Northern Epirus

- List of Greek countries and regions

References

- ^ Following G. Soteriadis: “An Ethnological Map Illustrating Hellenism In The Balkan Peninsula And Asia Minor” London: Edward Stanford, 1918. File:Hellenism in the Near East 1918.jpg

- ^ Douglas, Dakin (1962). "The Diplomacy of the Great Powers and the Balkan States, 1908–1914". Balkan Studies 3: 372–374. http://books.google.com/?id=oKQSAAAAIAAJ&dq=%22northern+epirus%22%2Bdeclared%2Bindependence&q=%22On+28+February+1914+however+Northern+Epirus+declared+its+independence+and+Venizelos+ordered+a+blockade+of+Santi-Quaranta%22. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- ^ Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). [http://books.google.com/?id=PDc-WW6YhqEC&pg=PA28&dq=%22northern+epirus%22%2Bflorence# v=onepage&q=%22northern%20epirus%22%2Bflorence&f=false The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact on Greece]. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 9781850657026. http://books.google.com/?id=PDc-WW6YhqEC&pg=PA28&dq=%22northern+epirus%22%2Bflorence# v=onepage&q=%22northern%20epirus%22%2Bflorence&f=false.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Konidaris, Gerasimos (2005). Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie. ed. The new Albanian migrations. Sussex Academic Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 1903900786, 9781903900789. http://books.google.com/?id=05Mw4-b9oN0C&pg=PA74&dq=omonoia+five#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ a b Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 77. ISBN 9781851094202. http://books.google.com/books?id=2YqjfHLyyj8C&pg=PA77. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ a b Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801-1927. Routledge. pp. 543–544. ISBN 9780714619743. http://books.google.com/?id=HaA18-u7mMMC.

- ^ a b c Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3: part 3, 2000

- ^ Smith, William (2006). A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology and Geography. Whitefish, MT, USA: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. pp. 423.

- ^ John Wilkes. The Illyrians. Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, p. 92. "Appian's description of the Illyrian territories records a southern boundary with Chaonia and Thesprotia, where ancient Epirus began south of river Aous (Vjose)." (Map)

- ^ Encyclopedia of the stateless nations: ethnic and national groups around the world. James Minahan. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 0313323844

- ^ Hammond, N.G.L. (1997). "Ancient Epirus: Prehistory and Protohistory". Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization (p. 36: Ekdotike Athenon): 34–45. ISBN 9789602133712. http://books.google.com/?id=UV1oAAAAMAAJ&q=%22Returning+to+Epirus,+we+may+put+the+first+arrival+of+Greek-speaking+Kurgan+peoples+at+2100+BC+,+when+one+of+their+inventions,+the+perforated+battle+axe+of+stone,+appeared.+It+was+about+this+time+that+they+took+control+of+Malik.+Early+in+the+Middle+Helladic+period,+1900-1600+BC,+they+took+possession+of+Northern+Epirus+and+created+two+units+of+power+or+Kingdoms.+Many+of+them+may+have+joined+in+the%22&dq=%22Returning+to+Epirus,+we+may+put+the+first+arrival+of+Greek-speaking+Kurgan+peoples+at+2100+BC+,+when+one+of+their+inventions,+the+perforated+battle+axe+of+stone,+appeared.+It+was+about+this+time+that+they+took+control+of+Malik.+Early+in+the+Middle+Helladic+period,+1900-1600+BC,+they+took+possession+of+Northern+Epirus+and+created+two+units+of+power+or+Kingdoms.+Many+of+them+may+have+joined+in+the%22.

- ^ Epeiros, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus

- ^ P. R. Franke, "Pyrrhus", in The Cambridge Ancient History VII Part 2: The Rise of Rome to 220 BC: 469, ed. Frank William Walbank. Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0521234468.

- ^ Bowden 2003

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians, 1992,ISBN-0631198075,Page 210

- ^ a b American journal of philology, Τόμοι 98-99,by JSTOR (Organization), Project Muse,1977,page 263, the partly Hellenic and partly Hellenized Epirus Nova

- ^ Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas by Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond,1976,ISBN-0815550472,page 54,The line of division between Illyricum and the Greek area Epirus nova

- ^ a b Winnifrith 2002

- ^ Stavro Skendi. The Albanian National Awakening, 1878-1912. Princeton University Press, 1967.

- ^ Greek, Roman and Byzantine studies. Duke University. 1981

- ^ Katherine Elizabeth Fleming. The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780691001944

- ^ Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. pp. 255. ISBN 9789602133712. http://books.google.gr/books?ei=F1mfTofMGcT44QT-hIW1BA&ct=result&id=UV1oAAAAMAAJ&dq=%22The+lasso+was+established+for+%22the+upkeep+of+the+common+Schools+in+the+city+for+the+dissemination+of+Greek+Letters+and%22&q=%22The+lasso+was+established+for+%22the+upkeep+of+the+common+Schools+in+the+city+for+the+dissemination+of+Greek+Letters+and+enlightenment+to+all+classes+of+citizens+of+both+sexes%2C+only+from+its+interest%2C+the+capital+remaining+untouched%22#search_anchor.

- ^ Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1991). Greeks in Russian military service in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Nicholas Charles Pappas. pp. 318, 324. ISBN 0521234476. http://books.google.com/?id=eAW5AAAAIAAJ&cd=1&dq=.

- ^ Surrealism in Greece: An Anthology. Nikos Stabakis. University of Texas Press, 2008. ISBN 0292718004

- ^ The military in Greek politics: from independence to democracy. Thanos Veremēs. Black Rose Books, 1998 ISBN 1551641054

- ^ Clogg 2002: 79. "In February 1913, Greek troops captured Ioannina, the capital of Epirus. The Turks recognised the gains of the Balkan allies by the Treaty of London of May 1913."

- ^ Clogg 2002: 81. "The Second Balkan War was of short duration and the Bulgarians were soon forced to the negotiating table. By the Treaty of Bucharest (August 1913) Bulgaria was obliged to accept a highly unfavorable territorial settlement, although she did retain an Aegean outlet at Dedeagatch (now Alexandroupolis in Greece). Greece's sovereignty over Crete was now recognized but her ambition to annex Northern Epirus, with its substantial Greek population, was thwarted by the incorporation of the region into an independent Albania."

- ^ James Pettifer. "The Greek Minority in Albania in the Aftermath of Communism" (PDF). Camberley, Surrey: Conflict Studies Research Centre, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. p. 4. http://www.da.mod.uk/search?SearchableText=greek+minority+in+Albania. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d Stickney 1926

- ^ Petiffer 2001: "In May 1914, the Great Powers signed the Protocol of Corfu, which recognized the area as Greek, after which it was occupied by the Greek army from October 1914 until October 1915."

- ^ Stavrianos, Leften Stavros; Stoianovich, Traian (2008). The Balkans since 1453. Hurst & Company. p. 710. ISBN 9781850655510. http://books.google.com/books?id=xcp7OXQE0FMC&pg=PA710. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ Griffith W. Albania and the Sino-Soviet Rift. Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1963: 40, 95.

- ^ a b c Roudometof, Robertson 2001: 189

- ^ Petiffer 2001: "Under King Zog, the Greek villages suffered considerable repression, including the forcible closure of Greek-language schools in 1933-1934 and the ordering of Greek Orthodox monasteries to accept mentally sick individuals as inmates."

- ^ a b c King, Mai, Schwandner-Sievers 2005: 173-194

- ^ George H. Chase. Greece of Tomorrow, ISBN 1406707589: 41.

- ^ Pyrrhus J. Ruches. Albania's Captives. Argonaut, 1965 (University of California).

- ^ a b c Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997

- ^ Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: Volume II: Albania in Occupation and War, 1939-45. Owen Pearson. I.B.Tauris, 2006. ISBN 1845111044.

- ^ Pyrrhus J. Ruches. 1965: 172 "The entire carnage , arson and imprisonment suffered by the hands of Balli Kombetar...schools burned".

- ^ Milica Zarkovic Bookman (1997). The demographic struggle for power: the political economy of demographic engineering in the modern world. Routledge. p. 245. ISBN 9780714647326. http://books.google.com/?id=q_Mv2IcQ0pQC&dq=.

- ^ Clogg 2002: 203 "Like all Albanians, the members of the Greek minority had suffered severe repression during the communist era and cross-border family visits had been out of the question. Although basic linguistic, educational and cultural rights were conceded there had been attempts to disperse the minority pressure had been applied on its members to adopt authentically "Illyrian" names."

- ^ Clogg 2002

- ^ Nußberger Angelika, Wolfgang Stoppel (2001) (in German). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien). Universität Köln. http://www.uni-koeln.de/jur-fak/ostrecht/minderheitenschutz/Vortraege/Albanien/Albanien_Stoppel.pdf

- ^ Petiffer 2001: "...under communism, pupils were taught only Albanian history and culture, even in Greek-language classes at the primary level."

- ^ a b c Petiffer 2001: "...the area studied was confined to the southern border fringes, and there is good reason to believe that this estimate was very low"."Under this definition, minority status was limited to those who lived in 99 villages in the southern border areas, thereby excluding important concentrations of Greek settlement in Vlorë (perhaps 8000 people in 1994) and in adjoining areas along the coast, ancestral Greek towns such as Himara, and ethnic Greeks living elsewhere throughout the country. Mixed villages outside this designated zone, even those with a clear majority of ethnic Greeks, were not considered minority areas and therefore were denied any Greek-language cultural or educational provisions. In addition, many Greeks were forcibly removed from the minority zones to other parts of the country as a product of communist population policy, an important and constant element of which was to pre-empt ethnic sources of political dissent. Greek place-names were changed to Albanian names, while use of the Greek language, prohibited everywhere outside the minority zones, was prohibited for many official purposes within them as well."

- ^ Frucht, Richard C. (2003). Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 148. ISBN 0203801091

- ^ Frucht, Richard C. (2003). Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 640. ISBN 0203801091

- ^ Valeria Heuberger, Arnold Suppan, Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996) (in German). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 71. ISBN 9783486561821. http://books.google.com/?id=edAu3dxEwwgC.

- ^ David Shankland. Archaeology, anthropology, and heritage in the Balkans and Anatolia Isis Press, 2004. ISBN 9789754282801, p. 198.

- ^ Olsen, Neil (2000). Albania. Oxfam. p. 19. ISBN 0855984325

- ^ Turnock, David (1997). The East European economy in context: communism and transition. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 0415086264

- ^ Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997: 190

- ^ Working Paper. Albanian Series. Gender Ethnicity and Landed Property in Albania. Sussana Lastaria-Cornhiel, Rachel Wheeler. September 1998. Land Tenure Center. University of Wisconsin. "Hoxha's regime maintained an extensive gulag...40 percent.

- ^ Petiffer 2001: "...onset in 1967 of the campaign by Albania’s communist party, the Albanian Party of Labour (PLA), to eradicate organised religion, a prime target of which was the Orthodox Church. Many churches were damaged or destroyed during this period, and many Greek-language books were banned because of their religious themes or orientation. Yet, as with other communist states, particularly in the Balkans, where measures putatively geared towards the consolidation of political control intersected with the pursuit of national integration, it is often impossible to distinguish sharply between ideological and ethno-cultural bases of repression. This is all the more true in the case of Albania’s anti-religion campaign because it was merely one element in the broader "Ideological and Cultural Revolution" begun by Hoxha in 1966 but whose main features he outlined at the PLA’s Fourth Congress in 1961.

- ^ Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997: "...with the demolition and the subsequent demolition of many churches, burning of religious books… general human rights violations. Christians could not mention Orthodoxy even in their own homes, visit their parents’ graves, light memorial candles or make the sign of the Cross."

- ^ Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Albania : Greeks, 2008. Online. UNHCR Refworld

- ^ Petiffer 2001: "In 1991, Greek shops were attacked in the coastal town of Saranda, home to a large minority population, and inter-ethnic relations throughout Albania worsened".

- ^ a b c Valeria Heuberger, Arnold Suppan, Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996) (in German). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 74. ISBN 9783486561821. http://books.google.com/?id=edAu3dxEwwgC&vq=nordepirus

- ^ Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997: 198

- ^ Clogg 2002: 214. "This war of words culminated in the arrest by the Albanian authorities in May of six members of the Onomoia, the main Greek minority organization in Albania. At their subsequent trial, five of the six received prison sentences of between six and eight years for treasonable advocacy of the secession of "Northern Epirus" to Greece and the illegal possession of weapons.

- ^ Greek Helsinki Monitor: Greeks of Albania and Albanians in Greece, September 1994.

- ^ Greek Ministry for Foreign Affairs: Bilateral relations between Greece and Albania.

- ^ World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous People: Albanian overview: Greeks.

- ^ "Albanian nationalists increase tensions with gunshots". Eleutherotypia. September 20, 2010. http://www.enet.gr/?i=news.el.politikh&id=194636. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Migration and Ethnicity in Albania: Synergies and Interdependencies. Kosta Barjaba. Watson Institute for International Studies. Nonetheless, it appears that the Albanian government is not going to conduct an official census, which would clarify the numbers. The Albanian government fears that if a census were adopted, a considerable part of the population would be registered as Greek.

- ^ a b "Bilateral relations between Greece and Albania". Ministry of Foreign Affairs-Greece in the World. http://www.mfa.gr/www.mfa.gr/en-US/Policy/Geographic+Regions/South-Eastern+Europe/Balkans/Bilateral+Relations/Albania/. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ^ Nicholas V. Gianaris. Geopolitical and economic changes in the Balkan countries Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996 ISBN 9780275955410, p. 4

- ^ "Country Studies US: Greeks and Other Minorities". http://countrystudies.us/albania/49.htm. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ^ ''Eastern Europe at the end of the 20th century'', Ian Jeffries, p. 69. 1993-06-25. ISBN 9780415236713. http://books.google.com/?id=kqCnCOgGc5AC&pg=PA68&dq=greek+minority+albania. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ "UNPO". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20061005102354/http://www.unpo.org/member_profile.php?id=23. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ^ Jelokova Z., Mincheva L., Fox J., Fekrat B. (2002). "Minorities at Risk (MAR) Project : Ethnic-Greeks in Albania". Center for International Development and Conflict Management, MAR Project, University of Maryland, College Park. http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/inscr/mar/data/albgrks.htm. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- ^ CIA World Factbook (2006). "Albania". https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/al.html. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- ^ The CIA World Factbook (1993) provided a figure of 8% for the Greek minority in Albania.

- ^ Kosta Barjarba. "Migration and Ethnicity in Albania: Synergies and Interdependencies" (PDF). http://www.watsoninstitute.org/bjwa/archive/11.1/Essays/Barjarba.pdf.

- ^ James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nation, 2002, pg. 547. Greenwood Press [1]

- ^ Ruches, Pyrros (1965). Albania's Captives. Chicago, USA: Argonaut. pp. 92–93

- ^ Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Albania: Greeks, 2008. UNHCR Refworld

- ^ Second Report Submitted By Albania Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1, of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- ^ Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities: Second Opinion on Albania 29 May 2008. Council of Europe: Secretariat of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- ^ Albanian Human Rights Pracitces, 1993. Author: U.S. Department of State. January 31, 1994.

- ^ a b George Gilson (27 September 2010). "Bad blood in Himara". Athens News. http://www.athensnews.gr/issue/13409/23391?action=print. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Macedonians and Greeks Join Forces against Albanian Census". balkanchronicle. http://www.balkanchronicle.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1364:macedonians-and-greeks-join-forces-against-albanian-census&catid=83:balkans&Itemid=460. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "Με αποχή απαντά η μειονότητα στην επιχείρηση αφανισμού της". ethnos.gr. http://www.ethnos.gr/article.asp?catid=22769&subid=2&pubid=63399185. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Ανησυχίες της ελληνικής μειονότητας της Αλβανίας για την απογραφή πληθυσμού". enet.gr. http://www.enet.gr/?i=news.el.article&id=300806. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Η ελληνική ομογένεια στην Αλβανία καλεί σε μποϊκοτάζ της απογραφής". kathimerini.gr. http://www.kathimerini.gr/4Dcgi/4dcgi/_w_articles_kathremote_1_29/09/2011_408566. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ "Albanian census worries Greek minority". athensnews. http://www.athensnews.gr/portal/10/48703. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Petiffer 2001: "Following strong protests by the Conference on Security... this decision was revered.

- ^ Human Rights Watch Report on Albania

- ^ Erlis Selimaj (2007-02-19). "Albanians go to the polls for local vote". Southeast European Times. http://setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2007/02/19/feature-02. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ Albania: Profile of Asylum claims and country conditions. United States Department of State. March 2004, p. 6.

- ^ Nußberger Angelika, Wolfgang Stoppel (2001) (in German). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien). Universität Köln. pp. 75. http://www.uni-koeln.de/jur-fak/ostrecht/minderheitenschutz/Vortraege/Albanien/Albanien_Stoppel.pdf

- ^ "Albanische Hefte. Parlamentswahlen 2005 in Albanien" (in German). Deutsch-Albanischen Freundschaftsgesellschaft e.V.. 2005. pp. 32. http://www.albanien-dafg.de/downloads/AH-3-2005.pdf.

- ^ Gregorič 2008: 68

- ^ Petiffer 2001: 4-5

- ^ a b King, Mai, Schwandner-Sievers 2005: 73

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b c "Tensions resurface in Albanian-Greek relations". Balkan Chronicle. 13 September 2010. http://www.balkanchronicle.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=602:tensions-resurface-in-albanian-greek-relations&catid=83:middle-east&Itemid=460. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

Bibliography

History

- Iorwerth E. S. Edwards, John Boardman, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (2000). The Cambridge Ancient History - The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. Part 3: Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521234476. http://books.google.com/?id=0qAoqP4g1fEC.

- Bowden, William (2003). Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province. Duckworth. ISBN 9780715631164. http://books.google.com/?id=ElFoAAAAMAAJ&dq=.

- Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804761710. http://books.google.com/?id=n4ymAAAAIAAJ.

- Ruches, Pyrrhus J. (1965). Albania's captives. Chicago: Argonaut. http://books.google.com/?id=01eQAAAAIAAJ&q=.

- Clogg, Richard (2002). Concise History of Greece (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80872-3. http://books.google.com/?id=H5pyUIY4THYC.

- Victor Roudometof, Roland Robertson (2001). Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313319495. http://books.google.com/?id=I9p_m7oXQ00C&dq=.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands-borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0715632019. http://books.google.com/?id=dkRoAAAAMAAJ.

Current topics

- Miranda Vickers, James Pettifer (1997). Albania: from anarchy to a Balkan identity. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 0715632019. http://books.google.com/?id=9IbgsDdeVxsC.

- Sussana Lastaria-Cornhiel, Rachel Wheeler (1998). "Working Paper. Albanian Series. Gender Ethnicity and Landed Property in Albania". Land Tenure Center. University of Wisconsin. http://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/21961/48_wp18.pdf?sequence=1.

- Petiffer, James (2001). The Greek Minority in Albania – In the Aftermath of Communism. Surrey, UK: Conflict Studies Research Centre. ISBN 1-903584-35-3. http://kms1.isn.ethz.ch/serviceengine/Files/ISN/38652/ipublicationdocument_singledocument/5494CBC6-4F56-4EFD-B6DB-7FB1EC46CC11/en/2001_Jul_2.pdf.

- Russell King, Nicola Mai, Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers (Ed.) (2005). The New Albanian Migration. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781903900789. http://books.google.com/?id=05Mw4-b9oN0C.

- Gregorič, Nataša (2008). "Contested Spaces and Negotiated Identities in Dhermi/Drimades of Himare/Himara area, Southern Albania". University of Nova Gorica. http://www.p-ng.si/~vanesa/doktorati/interkulturni/3GregoricBon.pdf.

Further reading

- Fred, Abrahams (1996). Human rights in post-communist Albania. Human Rights Watch/Helsinki. ISBN 9781564321602. http://books.google.com/?id=MkmGHvI-RyUC.

- Triadafilopoulos, Triadafilos (November 2000). "Power politics and nationalist discourse in the struggle for 'Northern Epirus': 1919-1921". Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans 2 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1080/713683343.

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the stateless nations: ethnic and national groups around the world. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 218. ISBN 0313323844. http://books.google.com/?id=K94wQ9MF2JsC.

External links

- Ethnographic map of Albania and neighbors, showing concentration of Greeks in Northern Epirus

- UNPO profile of the Greek minority in Albania

- Albania: the Greek minority by Human Rights Watch

- Assessment for Greeks in Albania by the Minorities at Risk (MAR) Project

- Greeks of Albania and Albanians in Greece by the Greek Helsinki Monitor

- Southern Albania, Northern Epirus: Survey of a Disputed Ethnological Boundary by Tom J. Winnifrith

- Research Foundation on Northern Epirus (I.B.E.)

- Northern Epirus: Hellenism Through Time

- Northern Epirot Youth

- Northern Epirus News Agency

- The Government of Epirus in Exile

- Unofficial Flag

Northern Epirus & Greeks in Albania History Ancient Epirus (Chaones • Dassaretae) • Despotate of Epirus • Revolt of 1854 • Revolt of 1878 • Himara revolt of 1912 • Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus • Protocol of Corfu • Battle of Morava-Ivan • Northern Epirus Liberation FrontSociety and Culture Greeks in Albania • New Academy • Zographeion College • Himariote dialect • Laiko Vima • Polyphonic song of Epirus • Postage stamps and postal history of Northern EpirusSettlements Ancient: Phoenice • Vouthroton • Apollonia • Thronium • Amantia • Antigonia • Antipatreia • Dimale • Oricum

Modern: Gjirokastër • Korçë • Himarë • Delvinë • Sarandë • Dropull • Pogon • Tepelenë • Permet • Leskovik • Ersekë • Moscopole • Bilisht

Other1: Nartë • Vlorë • Berat • Tirana • Elbasan • Durrës • Fier • ShkodërOrganizations Omonoia • Panepirotic Federation of America • Panepirotic Federation of Australia • Unity for Human Rights PartyIndividuals Benefactors: Alexandros Vasileiou • Apostolos Arsakis • Evangelos and Konstantinos Zappas • Ioannis Pangas • Georgios and Simon Sinas • Alexandros and Michael Vasileiou • Christakis Zografos • Literature: Theodore Kavalliotis • Katina Papa • Konstantinos Skenderis • Takis Tsiakos • Tasos Vidouris • Stavrianos Vistiaris • Andreas Zarbalas • Politics: Vasil Bollano • Georgios Christakis-Zografos • Vangjel Dule • Spiro Ksera • Military/Resistance: Kyriakoulis Argyrokastritis • Panos Bitsilis • Dimitrios Doulis • Konstantinos Lagoumitzis • Zachos Milios • Athanasios Pipis • Ioannis Poutetsis • Vasilios Sahinis • Spyromilios • Spyros Spyromilios • Sports: Pyrros Dimas • Sotiris Ninis • Panajot Pano • Leonidas Sabanis • Andreas Tatos • Clergy: Vasileios of Dryinoupolis • Panteleimon Kotokos Eulogios Kourilas

1 Cities and towns in Albania with Greek-speaking communities, outside the political definition of 'Northern Epirus'. Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.