- Night action at the Battle of Jutland

-

Main article: Battle of Jutland

Battle of Jutland Part of World War I

The Battle of Jutland, 1916Date 31 May 1916 – 1 June 1916 Location North Sea, near Denmark Result British dominance of the North Sea maintained Belligerents  Grand Fleet of the

Grand Fleet of the

Royal Navy

Commanders and leaders Sir John Jellicoe

Sir David BeattyReinhard Scheer

Franz HipperStrength 28 battleships

9 battlecruisers

8 armoured cruisers

26 light cruisers

78 destroyers

1 minelayer

1 seaplane carrier16 battleships

5 battlecruisers

6 pre-dreadnoughts

11 light cruisers

61 torpedo-boatsCasualties and losses 6,094 killed

510 wounded

177 captured

3 battlecruisers

3 armoured cruisers

8 destroyers

(113,300 tons sunk)[1]2,551 killed

507 wounded

1 pre-dreadnought

1 battlecruiser

5 light cruisers

6 Destroyers

1 Submarine

(62,300 tons sunk)[1]North Sea 1914–1918- U-Boat Campaign

- 1st Heligoland Bight

- 22 September 1914

- Texel

- 1st Yarmouth

- Scarborough

- Noordhinder Bank

- Dogger Bank

- 15 August 1915

- 2nd Dogger Bank

- 29 February 1916

- 2nd Yarmouth

- Jutland

- 19 August 1916

- 1st Dover Strait

- 16 March 1917

- 4 May 1917

- 2nd Dover Strait

- Lerwick

- 2nd Heligoland Bight

- Zeebrugge

- 1st Ostend

- 2nd Ostend

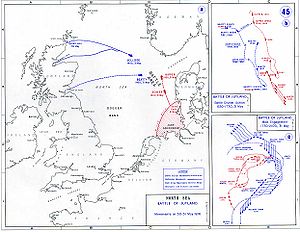

The Battle of Jutland took place in the North Sea between the German High Seas Fleet and British Grand Fleet on the afternoon and evening of 31 May 1916, continuing sporadically through the night into the early hours of 1 June. The battle was the only direct engagement between the two fleets throughout World War I. The war had already been waged for two years without any major sea battle, and many of the people present did not expect that this patrol would end differently. Lack of experience still accounted for a number of mistakes by the combatants. The battle has been described in a number of phases, the last of which is the subject of this article.

Prelude

The battle began when scouting battlecruiser forces of the two fleets met at around 1430 in the afternoon of the first day.

Initially the British force of six battlecruisers and four fast battleships commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty gave chase to five German battlecruisers commanded by Vice-Admiral Franz Hipper. The German ships set course back towards where they knew the main German fleet was waiting, planning to lead the British ships into a trap. Despite his numerical disadvantage, Hipper succeed in sinking two British battlecruisers during the chase. Once the German fleet came in sight, the British ships reversed course, now intending to lead the German fleet in pursuit of them back towards the main British fleet.

Despite minimal information, Admiral John Jellicoe managed to deploy his ships to good advantage across the path of the approaching German fleet, so that some success was gained in the short battle before the Germans in turn reversed course and withdrew. Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer was now in a difficult position, because his smaller force was cut off from Germany by the British fleet deployed across his escape route. He first attempted once again approaching the British positions, but was driven back. He then took up a position north west of the British, awaiting nightfall before making further attempts to escape.

Jellicoe declined to give chase to the German fleet after the second encounter because of the limited daylight remaining. He feared that the difficulties spotting and identifying ships in darkness would nullify his numerical advantage over the Germans, but was also confident that his deployment would prevent the Germans escaping past him in the night, and battle could be resumed the following day in conditions to his advantage. His battleships were redeployed from their battle line into closed up night cruising formation, with the battlecruisers deployed to his south west to prevent Germans passing south, and destroyers deployed behind the main fleet to intercept Germans passing to the north.

British ships had not trained for night action, but German ships had. The Germans had better searchlight control, using iris shutters which could rapidly switch on and off the light, star shell which could be fired over enemy ships to illuminate them without having to use a searchlight, which automatically presented a target for return fire. They used a system of coloured lights for recognition signals between ships, which the British could not duplicate, whereas the British used plain flashed morse signals, which the Germans were partly able to copy after once seeing them, giving some advantage when ships met. Scheer determined that his best chance was to pass the British fleet during the night.

German options

Scheer had four main escape routes, which were known to both admirals. He could change course away from the British fleet to the north-east and take a route through the Skagerrak channel north of Jutland back to safety in the Baltic. Although this might avoid the British, it was the longest route and risked some of his damaged ships sinking before reaching harbour. Jellicoe discounted the route, because of these considerations but also because the other escape routes all lay to the south, and he could not guard both directions. The longer route might also allow his faster ships to catch up the following day should Scheer go that way.

The next possibility was via a gap cleared through the middle of the minefields laid by both sides in the Heligoland Bight. Scheer had taken this route on the way out, but the uncertainties in knowing their precise position after the battle and locating the seaward end of the channel would make it risky as a return route.

The third choice was around the minefields to the North Frisian coast and thence east to the River Ems and Jade. This was 180 miles, but Jellicoe had a report of the German fleet heading west south west, which was the course for this route and it would take Scheer generally away from the British. Jellicoe believed this was the most likely route for the Germans to take, so set a course south at seventeen knots, faster than the German ships could manage, which should put him in a position to locate and overtake the German fleet at daylight.

The shortest route of 100 miles was via Horns Reef to the SSE, passing north of the minefields laid by both sides in the Heligoland Bight. It was this route which Scheer chose despite having to pass the British fleet. Although it was not Jellicoe's best guess at Scheer's actions, he anticipated that the destroyers and cruisers spread out around his fleet would give warning should the German's take this route, and his general course would still allow him to intercept.[2]

British deployment

See also: Order of battle at JutlandThe British moved into night formation at 2117. Sunset had been at 2000, with full darkness by 2100. The ships were travelling approximately SSE with the battleships in four columns one mile apart which were intended to travel parallel courses in a compact block giving minimum opportunity for surprise torpedo attack. The western column comprised the Second Battle Squadron of eight ships commanded by Martyn Jerram. The next column one mile to the east was the Fourth Battle Squadron led by Iron Duke, Jellicoe's flagship. Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee on HMS Benbow commanding the fourth division (a division of four ships being half a squadron of eight), was second in command of this squadron. The third column consisted of the First Battle Squadron commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir Cecil Burney from Marlborough. Marlborough had been damaged by a torpedo strike but reported she could keep up with a speed of seventeen knots. This proved optimistic, with the result that the half-squadron 5th division maintained its allotted position, but Marlborough and the other three ships of the 6th division fell progressively behind. The Fifth Battle Squadron commanded from HMS Barham by Hugh Evan-Thomas of only three fast battleships (Warspite having returned to port damaged after taking part in the initial battlecruiser action), took up a position between the two separating halves. At 2203 the 5th Battle Squadron reversed course for five minutes so as to fall back closer to Marlborough.[3]

The battlecruisers commanded by Beatty were stationed fifteen miles WSW of Iron Duke, which it was anticipated would put them in a good position to intercept German ships. Their position meant that at approximately 2130–2200 they were positioned unbeknownst to either side eight miles ahead of and leading the German battlefleet.[4]

The British fleet included smaller vessels used for screening and scouting purposes. The first Light Cruiser Squadron (LCS) commanded by commodore Edwyn Alexander-Sinclair and the third LCS commanded by Rear-Admiral Napier were ordered to accompany Beatty. William Goodenough's second Light Cruiser Squadron was stationed north of Burney's 1BS, behind the fleet.[5] The fourth LCS commanded by Commodore Charles Edward Le mesurier was placed ahead of the fleet, and the Second Cruiser Squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral H. L. Heath was stationed east of the battleships.[6]

The destroyers attached to the fleet were ordered to take stations approximately five miles behind. Jellicoe stated he had three reasons for their placement: to guard against surprise attack by German torpedo boats, to attack any major German ships should they attempt to pass the fleet, and to keep the destroyers clear of major British ships. Jellicoe recognised that identifying ships in the dark was difficult, and wanted to ensure there could be no confusion by keeping his destroyers away from the British capital vessels. However, his orders at the time failed to make clear to the destroyers the position of other British vessels, so that in fact considerable confusion did arise later when the destroyers encountered large vessels. Overall control of the destroyers was given to Commodore Hawksley on the light cruiser Castor, but individual destroyer flotillas were inexperienced in joint operations, particularly at night. The principle weapon of the destroyer was the torpedo, and this was most effective if used in salvoes fired from several ships at once, making it hard for enemy ships to dodge every torpedo.[7]

At 2205 the minelayer HMS Abdiel was detached from the fleet and ordered to lay her mines off the Horne's Reef, in anticipation that German ships might attempt to flee in that direction.[7]

German deployment

The German fleet continued in a similar deployment to that which it had used during the day, a single column in line ahead. At 2125 Scheer ordered his fleet to a course of 142 degrees. Westfalen was slow in responding, so Scheer issued an adjusted course of 137 degrees at 2146. Westfalen misinterpreted the signal and thus turned to 156 degrees, finally turning to 133 degrees as instructed at 2232. At 2300 the course to head directly for the Horns Reef light ship was set at 130 degrees and Westfalen had complied by 2320.[8]

Scheer felt it inadvisable for the relatively weak II Battle Squadron of pre-dreadnought battleships to remain at the head of the German line, where they had ended up after the multiple course reversals of the day and they were ordered to move to the rear. The maneuvre was delayed since at 2130 Hannover now leading the pre-dreadnought squadron sighted four large ships ahead, and a light inadvertently showing on the mast of HMS Shannon of the 2nd British Cruiser squadron. Once the British ships had passed ahead, the II squadron turned north at 2150 and took station at the rear at 2210. Progress of the whole line was delayed slightly by the repositioning so that it fell back more to the north of the British ships. Westfalen at the head of the 1st Battle Squadron now led the revised column of battleships, followed by the III Battle Squadron and then the pre-dreadnought II Battle Squadron.[9]

The II Scouting Group of cruisers was placed ahead of the battleships, while the IV Scouting Group was similarly placed to starboard.[10] The IV SG under Commodore von Reuter mistook its position in the dark, so ending up on the port side of the battle line rather than starboard.[11]

The battlecruisers were ordered to take positions at the rear behind II Squadron, because of their severe battle damage. Admiral Hipper had been forced to leave his flagship SMS Lützow and had some trouble boarding another ship in the course of the battle. At 2115 he boarded Moltke and again assumed command, initially mistakenly ordering the ships to move to the head of the column. Only Seydlitz and Moltke could immediately comply: Derfflinger had too many holes to travel at speed, and Von der Tann needed to clean ash from her boilers forcing her to steam slowly. When Derfflinger and Von der Tann drew abreast of the flagship Friedrich der Grosse, Scheer once again ordered them to the rear. The two joined the end of the German column, but Seydlitz and Moltke remained out of position initially ahead of the fleet and had to move independently through the British fleet.[12] Lützow proceeded southwards behind the fleet for the first couple of hours of the night at the best speed she could manage, seven knots, but eventually sank at 0145.[13]

Intelligence

British intelligence about the whereabouts of German vessels suffered a number of failures throughout the battle of Jutland. There were two sources of information: intercepted German wireless messages and direct sightings by British ships. Although intercepted messages had clear importance, they suffered delay while they were received, decoded and passed back to the fleet, but also were subject to intelligence misunderstandings, or the simple incorrect reporting by German ships regarding their own whereabouts. Exact positioning was imprecise for all ships, because they frequently changed course during battle and it was impossible to track the changes. The British and German fleets had an idea of their relative positions, but different views of their absolute positions.

Jellicoe had received reports of fighting between the battlecruisers and light ships attached to Jerrams's squadron, which had been leading the British column as darkness fell. The German battlecruisers, which had led the German fleet and the pre-dreadnought squadron nearby, were subsequently ordered to move to the rear of the German column, because of the severe damage already received by the battlecruisers, and the pre-dreadnaughts proper position as the weakest ships being towards the rear. The British thus received a false impression of the most southerly of Scheer's ships being the general position of his fleet. At 2138 jellicoe received a report from Beatty stating the German ship's course was WSW. In fact, Scheer had adopted a course slightly east of SSE from 2114, which he maintained thereafter taking him directly towards Horne's Reef, except when temporarily diverted by British ships. At the time of Beatty's message, the German ships were only eight miles away and closing slowly.[7]

The admiralty attempted to keep Jellicoe informed about German messages, but failed to get across the significance of information they had received.

At 2045 Scheer sent a message to Commodore Michelson on SMS Rostock to organise a torpedoboat attack against the British. At 2155 the admiralty passed this information to Jellicoe, which helped convince him that fighting heard and seen during the night was a result of this attack, rather than anything involving the main German fleet.[14]

At 2123 Jellicoe was passed a position report from 2100 of the rearmost section of the German fleet, on course due south. The position was wrong due to German navigation errors, although the course was correct at that time. The position was not credible as it placed the German ship south of his own position at the time he received the intercept, contrary to reports from his own ships of German positions, and the result was to increase his distrust in such intercepts. Jellicoe stated afterwards that he would always trust a report from one of his own ships rather than an intercept, although other analysis later demonstrated that these reports too contained errors or could be misleading.[14]

At 2106 Scheer requested a morning reconnaissance by Zeppelins of Horn's Reef, strongly suggestive he intended to pass that way.[7] This information was not passed to Jellicoe, who instead at 2330 received only a composite summary of four messages decoded between 2155 and 2210, stating without explanation that the German fleet was returning home course SSE3/4E at 16 knots. Although in this case the information was entirely correct it contradicted information received from Southampton and Nottingham about contacts with the German fleet, which turned out to be misleading. Shorn of its details, the summary failed to convince: Jellicoe stated afterwards that had he received the specific information requesting air reconnaissance, he would have believed the report.[15]

At 2315 a further message from Scheer was decoded (sent at 2232), confirming he was on course SEbyS. Another was sent at the same time by Michelson to his torpedo boats, ordering them to assemble at 0200 at Horn reef, or to take a course around the Skaw (to Germany). Scheer sent another report of his course and position at 2306 (decoded by 2350) and further consistent course reports indicating his progress at 2330, 2336, 0043 and 0103 each decoded within about half an hour. None of these was passed on to Jellicoe. At 0148 the admiralty did report the position of the sinking Lutzow and that German submarines had been ordered to sea, and at 0312 where Elbing had been abandoned.[16]

The German navy also managed to intercept British wireless messages, and Scheer received information about the disposition of British ships for the night, in particular that the destroyers had been posted behind the fleet. Once news of contact with destroyers began to arrive, he could proceed with some confidence of avoiding the enemy capital ships.[14]

Engagements

Throughout the night different opposing ships came into contact in an arc as the German fleet proceeded from west to east across the tail of the British fleet. The two fleets were on similar courses so the encounter was drawn out over several hours, but at no time did the British get a clear picture of what was happening. The action was characterised by determination and nerve on the German side to keep a steady course despite continual encounters with British destroyers, but by confusion and failure to report events by the British. Individual British ships showed considerable courage and determination in carrying out attacks, but their efforts were spoilt by confusion, which meant many ships turned away from possible targets, uncertain that they were enemy vessels.

German torpedoboat diversionary attack

Scheer ordered Commodore Michelson on the light cruiser Rostock, commanding destroyers attached to the main fleet, to organise a diversionary attack against the British. To do this he needed to locate those destroyers which still had sufficient torpedoes remaining, and shortly discovered that Commodore Heinrich in the light cruiser Regensburg, who commanded destroyers attached to the battlecruiser force, had already independently organised such an attack aimed at the ships sighted by Hannover. At 2045 Heinrich had ordered the second torpedoboat flotilla under captain Schuur together with three boats from the sixth flotilla (from the XII half-flotilla) under Kapitanleutnant Lahs, all positioned at the rear (north) of the German fleet, to stage an attack to the east of the German position. At 2056 Michelson added the V Flotilla under Commander Heinecke and the VII Flotilla under Commander von Koch from his own command to attack more to the south.[17]

The II torpedoboat flotilla encountered the II Light Cruiser Squadron commanded by Goodenough and the XI destroyer flotilla commanded by Commodore Hawksley on Castor. There was still enough light for the attackers to be spotted before getting sufficiently close, and they were forced to retreat to the west. The VI flotilla was also forced back west, receiving fire for 20 minutes at ranges of 3,300 to 5,500 yards. S50 was struck by a shell which severed a main steam pipe, reducing her speed to 25 knots, affecting her steering and electrical power so that she had to return to the main fleet. Lahs turned eastward again at 2110 and Schuur at 2140, but now found themselves too far north. The attack was abandoned and the destroyers headed for the Skaw and a return to Germany, together with the third flotilla which had also become left behind.[17][18]

Michelson's attack also suffered from lack of information about the location of the enemy. The V and VII flotillas comprised older and slower boats, which were further hampered by having been steaming at high speed for some hours, meaning the stokers were tired and boiler fires choked with slag so they could only manage 17 knots. Michelson intended the VII flotilla to patrol a sector from south east to south by east ahead of the fleet. The V flotilla was ordered to cover the sector from south by east to south south west. The ships were initially stationed to the west of Konig at the rear of the battle line, so Michelson intended them to move to the head of the fleet before spreading eastwards. Instead they were forced to pass through the German line to try to achieve their positions.[19] At 2130 Koch's boats came under friendly fire from battleships of the third battle squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Behncke, though escaped damage. They were further hampered by the need to minimise sparks from the funnels which might give away their position. The result of all these difficulties was that they first met destroyers at the rear of the British fleet rather than the capital ships further ahead. At 2150 Koch sighted the fourth Destroyer Flotilla under Captain Wintour on the destroyer leader Tipperary heading north to their night station. Initially he mistook the ships for the German II Flotilla, but they failed to answer a flashed recognition signal, which the British did not see. At 500 yards S24, S16, S18 and S15 each fired one torpedo. The attack failed because the British ships changed course to south having just reached their assigned position, but one ship edit] Second Scouting Group and Eleventh destroyer Flotilla

At around 2140 the light cruisers Frankfurt and Pilau of the second scouting group under Rear-Admiral Bodicker sighted Castor and the eleventh destroyer flotilla, consisting of Castor,, kempenfelt and fourteen 'M' class destroyers.[8] Frankfurt reported the enemy to Scheer at 2158, but misidentified the British as a group of five cruisers. The German ships each fired one torpedo at a range of 1100m without using lights or firing guns, so that the British remained unaware of their presence. The German ships withdrew, having realised the ships were not cruisers and not wishing to draw them towards the main German column, The British ships failed to see the torpedoes, which once again went wide because the British squadron which had initially been heading north-east was in the process of turning south into position behind the fleet.[22][23]

Half an hour later the eleventh Flotilla was again spotted by German ships, this time by the IV Scouting Groups, to which Elbing and Rostock had become attached. The Germans were spotted approaching, but having earlier seen the British challenge signal in use, were able to signal the British ships and continue to approach. At about 1 mile range, the German ships switched on searchlights and opened fire. Castor returned fire, and she and two of the destroyers, Marne and Magic each fired one torpedo at the German ships. The exchange lasted for about five minutes before both sides turned away. Some of the other destroyers reported that they were unable to see the enemy because of glare from Castor's guns, while others believed there had been some mistake and this was 'friendly fire'. Hamburg received some damage, while one of the torpedoes passed underneath Elbing. Castor received ten hits, killing twelve men and wounding 23 more, while her motor boat was set on fire illuminating the whole ship. Hawksley declined to follow the German ships as they withdrew, instead maintaining station behind the fleet. Garland and Castor reported contact with enemy light forces, which was also seen and heard by Jellicoe.[24][25]

Reuter's Fourth Scouting Group and Goodenough's Second LCS

At around 2215 the second LCS under Goodenough sighted five ships at a distance of 1500 yards. After a few minutes confusion, both sides opened fire almost simultaneously, with the four leading German ships concentrating fire upon Southampton, and the fifth firing at Dublin. Nottingham and Birmingham did not show lights, and as a result were not fired upon. Southampton suffered considerable damage, particularly to the upper decks, but managed to fire a torpedo which hit the light cruiser SMS Frauenlob of the fourth scouting group commanded by Commodore von Reuter. Frauenlob sank with only five survivors from the crew of 330.[26]

The battleship SMS Westfalen altered course to south in order to avoid the conflict, but was ordered back to the original course at 2234, which Scheer perceived should now only be guarded by light forces. Jellicoe could also see that some action was taking place to his north. Goodenough reported the contact, though this was delayed as it had to be done via Nottingham as Southampton's radio had been shot away. Birmingham became separated from the squadron, but at 2315 passed on a brief sighting of German battlecruisers headed west by south. This tended to discredit the Admiralty intelligence report of Scheer's intentions received at 2330, which stated German battlecruisers were now stationed at the rear of the fleet, which was headed ESE. Birmingham had sighted the ships while temporarily turned away to avoid British vessels.[14]

Fourth destroyer flotilla

The 4th destroyer flotilla commanded by Captain Charles Wintour onboard Tipperary was the most westerly group of British destroyers keeping station behind (north) of the Grand Fleet, heading south. Two destroyers had been sunk and five were accompanying the battlecruisers, so the leaders tipperary and Broke were left with ten 'K' class destroyers.[8]

At around 23.15 Leading Torpedoman Cox on board Garland, fourth ship in the twelve strong line, sighted three ships approaching. These were reported to Captain Wintour, who being unable to determine whether the ships were British or German issued a British challenge signal to the approaching ships. This was immediately answered by a hail of fire at a range of around 600 yards from the approaching German light cruisers, SMS Stuttgart, SMS Hamburg, SMS Rostock and SMS Elbing. Shortly behind them, the battleships SMS Westfalen and SMS Nassau also opened fire with their secondary armament. The ships were the van of the German High Seas Fleet, which was passing behind the British fleet.[27]

The leading British ships, Tipperary, Spitfire, Sparrowhawk, HMS Garland,

HMS Broke, the Destroyer Leader that collided with Sparrowhawk at Jutland

- Nigel Steel; Peter Hart (2003). Jutland 1916. London: Cassell (Orion books). ISBN 030436648-X.

- Geoffrey Bennett (1964). The battle of Jutland. B. T Batsford Ltd..

- John Campbell (1986). Jutland: an analysis of the fighting. London: Conway Maritime press Ltd..

- V. E. Tarrant (1995). Jutland, the German perspective. London: Cassell military paperbacks. ISBN 0304358487.

- ^ a b Nasmith, pg261

- ^ Steel & Hart pp. 284–285

- ^ Campbell p.274

- ^ Bennett p.128

- ^ Bennett p. 128

- ^ Campbell P.274

- ^ a b c d Bennett p.129

- ^ a b c d e Campbell P.275

- ^ Tarrant pp. 204–205

- ^ Steel & Hart p. 288

- ^ Tarrant p.205, 211

- ^ Steel & Hart pp. 288–289

- ^ Campbell p.276

- ^ a b c d Bennett P. 134

- ^ Bennett P.135

- ^ Bennett P. 147

- ^ a b Bennett P.130

- ^ Tarrant p.196

- ^ Tarrant pp. 202–204

- ^ Bennett p.131

- ^ Tarrant pp. 211–212

- ^ Tarrant p. 213

- ^ <Campbell p.279

- ^ Bennett pp. 131–132

- ^ Campbell pp. 279–280

- ^ Bennett pp. 133–134

- ^ Steel & Hart pp. 309–310

- ^ Steel & Hart pp. 311–313

- ^ Bennett P. 137

- ^ a b Bennett P.138

- ^ Steel and Hart p.318

- ^ Jutland 1916, p.320

- ^ Bennett p.141

- ^ Bennett pp. 141–142

- ^ Steel & Hart p. 374

- ^ Bennett P.142

- ^ Bennett P. 144

- ^ a b Bennett P. 145

- ^ Bennett P. 146

- ^ Bennett pp. 147–148

- ^ Steel & Hart P.283

Sub Lieutenant Percy Wood saw Broke coming towards them at 28 knots, heading directly for Sparrowhawk's bridge. He shouted warnings to crew on the foc'sle to get clear, and then was knocked over by the impact. He awoke to find himself lying on the deck of Broke. Wood reported to Commander Allen, who told him to return to his own ship and make preparations there to take onboard the crew of Broke. Two other men from Sparrowhawk were also thrown onto Broke by the collision. Returning to Sparrowhawk, Wood was told by his own captain, Lieutenant Commander Sydney Hopkins, that he had just sent exactly the same message across to Broke. Approximately 20 men from Sparrowhawk evacuated to Broke, while fifteen of Broke's crew crossed to Sparrowhawk.

At this point a third destroyer, HMS Contest steamed into Sparrowhawk, striking six feet from her stern. Contest was relatively unharmed and able to continue underway after the collision. Broke and Sparrowhawk remained wedged together for about half an hour before they could be separated and Broke got underway, taking 30 of Sparrowhawk's crew with her. Broke remained able to manoeuvre, although she had lost her bow.[32] At around 1.30 AM the ship again encountered German destroyers which fired about six rounds into Broke, which managed to return one shot before the ships separated. The ship proceeded slowly towards Britain but by 0600 on 2 June found that she could no longer travel into the high seas with her damaged bow and had to turn back towards Heligoland. The seas abated and the ship was able to head for the Tyne, arriving some two and a half days after the engagement.[33]

Sparrowhawk still had engine power but the rudder was jammed to one side so she could do nothing except steam in circles, near the burning destroyer Tipperary. At around 0200 a German torpedo boat approached, coming within 100 yards, but then turned away. Only one gun was still functional, which the captain and his officers manned personally as the gun crews had been killed or injured, but they held fire in the hope the German would not initiate an attack Sparrowhawk could not hope to survive. Shortly after, the Tipperary sank, putting out the fire which was attracting attention to the area. At around 0330 Sparrowhawk sighted a German cruiser, again causing considerable alarm, but shortly afterwards the ship was seen to list and then sink bow first. This was the SMS Elbing, which had been torpedoed and then abandoned. At 0610 a raft approached, carrying 23 men from the Tipperary: three were found to be already dead, while five more died after being taken on board. An hour later three British destroyers arrived and edit] Thirteenth destroyer flotilla

East of the fourth flotilla was the thirteenth, commanded by Captain Farie on the light cruiser champion. This had lost three of its original complement of ten 'M' class destroyers, but had gained the Termagant and Turbulent from the 10th flotilla.[8] At 2330 fighting was observed to the west and Farie decided to reposition his ships further to the east to get a clear view of the enemy. However, as he failed to signal his intentions to his flotilla, who were following the ship in front while showing no lights, only his first two destroyers, Moresby and Obdurate, followed on. His movements also caused other destroyers stationed east of him to move further east, which had the effect of clearing the way for the oncoming German fleet. His last two destroyers which had been left behind, Menace and Nonsuch of the twelfth flotilla were nearly rammed by the oncoming Frankfurt and Pillau. Farie also failed to report his sightings or actions.[37]

German battlecruisers

The German battlecruisers were ordered to the rear of the fleet at night because of the damage they had sustained. Seydlitz was only able to make 16 knots and was ordered to make her own way to Horn's reef. Moltke also lost contact with the fleet and had to proceed independently. At 2230, Captain von Karpf on Moltke sighted ships of the second battle squadron and was seen by the rearmost battleship, Thunderer (Captain James Ferguson). Ferguson neither fired upon Moltke, nor reported his sighting, because it was considered inadvisable to show up our battlefleet. Moltke steered away to the west, before trying again later to turn SSE to Horn's reef. At 2255 she again sighted the British ships and turned back undetected, and then once again at 2320. Hipper then ordered Moltke to proceed south, so that she could pass ahead of the British fleet, which she did around 0130.[38]

Seydlitz was sighted at about 2400 by Marlborough, who did nothing. The second ship in the squadron, Revenge (Captain Kiddle) challenged the unidentified ship, and received the wrong response, but took no action. Agincourt (Captain Doughty) at the rear of the line spotted her but did not challenge her so as not to give our division's position away. Light cruisers Boadicea and Fearless (Captain Roper) also spotted Seydlitz, but followed the example of the battleships and did nothing. Roper stated that by the time he could identify the ship, it was too late to fire a torpedo at her (Fearless was capable of 25 knots compared to Seydlitz's maximum 16 knots because of the damage). Seydlitz, already badly damaged and unable to put up much of a fight, was able to limp back to Germany.[38]

Commander Goldsmith's combined flotillas

Commander Goldsmith had command of eight destroyers from the combined ninth and tenth flotillas. However, unknown to him, the six 'lost' ships from the thirteenth flotilla had joined on to his line of ships. The German first battle squadron would have passed behind Goldsmith's ships, but now passed through the line of destroyers, in front of the last four. The first two were too close to attack: the third, Petard, had no torpedoes remaining so put on full speed and attempted to get clear. Petard passed ahead of the Westfalen and got away under fire with some damage, but Turbulent following behind was rammed by Westfalen and sunk with all the crew being lost. Once again, the sightings and events were not reported to Jellicoe.[39]

Twelfth flotilla

The twelfth flotilla commanded by Captain Stirling on the destroyer leader Faulknor was following behind the First Battle Squadron. This had fallen behind the main fleet because damage to Marlborough had reduced her speed, so the destroyers were now some 10 miles behind Jellicoe. The flotilla had thirteen 'M' class destroyers plus Faulknor and another destroyer leader, edit] Critiques

The battle of Jutland has attracted enormous debate throughout the century since it took place. It was perceived by many that the British fleet, considered superior to that of Germany, had failed to achieve even a numerical victory, never mind a decisive one. Although significant losses had happened in ships commanded by Beatty, he had succeeded in leading the German fleet to Jellicoe, and it was perceived in some quarters that Jellicoe had then let them escape. Jellicoe's perceived timidity, both in failing to pursue the German fleet when it turned away during daylight, and his entirely defensive posture at night were cited against him. However, both these actions were in line with a policy agreed before hand with the admiralty, that the simple existence of the superior British fleet denied Germany access to the North Sea and ensured the safety of surface shipping at least from attack by surface German vessels. Engaging the enemy in any circumstances where other factors would nullify this normal advantage risked losing the protection which the fleet afforded simply by existing. This accorded with theories of sea power, as expounded by the American naval strategist Mahan, or the British writer Sir Julian Corbett. German admirals also were conscious of the significance of a 'fleet in being', refusing to engage in any fleet to fleet action throughout the war. Instead, their strategy was to attempt to ambush patrolling smaller groups of British ships and thereby whittle down British numbers in the hope of winning an eventual full scale confrontation. In this they failed, not least because British shipbuilding capacity meant the relative strength of the British fleet increased rather than reduced as the war progressed. They too believed in the importance of preserving their ships for future opportunities, and that their own 'fleet in being' significantly tied up the Royal Navy endlessly patrolling the North Sea and preventing it taking part in war efforts elsewhere.[41]