- David Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty

-

Admiral of the Fleet The Earl Beatty

Born 17 January 1871

Nantwich, Cheshire, EnglandDied 11 March 1936 (aged 65)

London, EnglandAllegiance  United Kingdom

United KingdomService/branch  Royal Navy

Royal NavyYears of service 1884–1927 Rank Admiral of the Fleet Commands held Battlecruiser Squadron (1913–1916)

Grand Fleet (1916–1918)

First Sea Lord (1919–1927)Battles/wars - Battle of Dongola

- Battle of Omdurman

- Battle of Heligoland Bight

- Battle of Dogger Bank (1915)

- Battle of Jutland

Awards Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

Order of Merit

Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

Distinguished Service OrderAdmiral of the Fleet David Richard Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty, GCB, OM, GCVO, DSO (17 January 1871 – 11 March 1936) was an admiral in the Royal Navy. Achieving career success at an early age, he commanded the British battlecruisers at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, a tactically indecisive engagement after which his aggressive approach was contrasted with the caution of his commander Admiral Jellicoe. Later in the war he succeeded Jellicoe as Commander in Chief of the Grand Fleet, in which capacity he received the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet at the end of hostilities, and then in the 1920s he served a lengthy term as First Sea Lord (head of the Royal Navy).

He is best remembered today for his comment that "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today" at Jutland, where three of his battlecruisers exploded and sank under German fire exacerbated by design faults and poor strategy.

Contents

Family and childhood

Beatty was born at Howbeck Lodge in the parish of Stapeley, Cheshire, on 17 January 1871.[1] He was the second son of five children born to David Longfield Beatty (1840−1904) and Katherine (or Katrine) Edith Sadleir (1840−1896), both from Ireland. Beatty's father had been an officer in the Fourth Hussars where he formed a relationship with the wife of another officer. The two were unable to marry until after Katrine had obtained a divorce on 21 February 1871, after the birth of their first two sons. Beatty's birth certificate recorded his mother's surname as Beatty, and their eventual marriage at St Michael's Church, Liverpool was kept secret.[2] Beatty's other brothers were Charles Harold Longfield (1870–1917) who served with distinction in the South Africa wars before dying from complications after losing an arm in Flanders, Richard George (1882–1915) who died on active service in India, William Vandeleur Schruder (1873–1935) who became an army Major and Newmarket horse trainer, and one sister Kathleen Roma (1875–).

Katrine had fair hair and blue eyes, soft wide lips, and overall an air of command. Beatty's father was 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) tall, dark haired with big hands and feet. Both David and his elder brother Charles were short, about 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m) with small hands and feet. Charles was fair haired taking after his mother's features, whereas David had more the look of his father. After the affair between David and Katrine became known, David Longfield's father (Beatty's grandfather), David Vandeleur Beatty (1815–1881), arranged for his son to be posted to India in the hope that the scandalous relationship might end. Beatty resigned from the regiment on 21 November 1865, with the honorary rank of Captain. He took up residence with Katrine in Cheshire and in 1869 sold his commission.[3]

Early education concentrated on horsemanship, hunting and learning to be a gentleman. Beatty had a close relationship with his elder brother Charles, who became his ally against their oppressive and overbearing father. They remained close throughout life, so much so that the only time Beatty felt despair was at his brother's death. Beatty later wrote to his wife about Charles, we lived together, played together, rode together, fought together. [4] His brothers would later join the British Army, but early on young David developed an interest in ships and the sea and expressed a desire to join the Royal Navy. In 1882 he entered Burney's Naval academy at Gosport, which was a 'crammer' for boys wishing to take the entrance examinations for the Royal Navy.[5] His early experience in a harsh environment was to stand him in good stead for navy life.

In 1881 Beatty's grandfather died and his father succeeded to the 18th century mansion, 'Borodale', outside Enniscorthy, in County Wexford. After retiring from the army he had established a business training horses first in Cheshire and then at 'The Mount', near Rugby. On inheriting and following the death of his wife at 'The Mount', he returned to Ireland abandoning the training business.[6]

Marriage

In 1898 Beatty returned from leave after the Sudan campaign, but finding life in Ireland at the family home not to his taste, stayed instead with his brother at Newmarket. The location allowed him good hunting, and access to aristocratic houses where his recent heroic reputation from the campaign made him an honoured guest. Out hunting one day he chanced to meet Ethel Tree (1873-17 July 1932, Northamptonshire), daughter of Chicago department store founder Marshall Field. Beatty was immediately taken with her, for her good looks and her ability to hunt. The immediate difficulty with the match was that Ethel was married already to Arthur Tree, with a son, Ronald.[7]

Beatty was posted to the China squadron and only returned to England after being wounded at the siege of Tsientsin, eighteen months later in August 1900. The couple had at first exchanged letters, which Beatty signed 'Jack', as Ethel was still a married woman and discretion was advised. Ethel became involved with another man and the exchange of letters ceased but on Beatty's return she sent him a telegram and letter inviting him to resume their friendship. Beatty did not respond until after surgery on his arm in September 1900 when he wrote, I landed from China with my heart full of rage, and swore I did not care if I ever saw you again, or if I were killed or not. And now I have arrived with the firm determination not to see you at all in my own mind... Unfortunately I shall go on loving you to the bitter end... To me always a Queen, if not always mine, Good-bye.[8]

Despite this estrangement, the couple again met foxhunting and resumed a discreet relationship. Marshall Field was at first unimpressed by the impecunious Beatty as a future son-in-law, but was persuaded by his heroic reputation, impressive record of promotion and future prospects. There was the possibility that Field might revoke the settlement he had made on his daughter at the time of her first marriage and the new couple would have no means of support. Beatty's father was also unhappy about the match, fearing a repeat of the difficulties he had faced with his own relationship with a married woman, but with the added risk of publicity because both Beatty and Ethel were famous and the risk that Beatty's illegitimacy might be exposed. Beatty went so far as to consult a fortune teller, Mrs. Roberts, who predicted a fine outcome to the match. Ethel wrote to Arthur, telling him that it was her firm intention never to live with him again as his wife, though not naming any particular person or reason. Arthur agreed to cooperate, and filed for divorce in America on the grounds of desertion, which was granted 9 May 1901. Beatty and Ethel married 22 May 1901 at the registry office, St. George's, Hannover Square, London with no family attending. Although Arthur Tree was himself from a wealthy American family, he now had to adjust to reduced circumstances without Ethel's support. He elected to remain in Britain and their son Ronald remained with him. Ronald and his mother were never reconciled from his perception that she had deserted his father, but he visited in later life and became friendly with Beatty. Ronald later became a member of parliament, during World War II became a link between the British and United States governments, and lent his country house, Ditchley Park near Oxford, to Churchill for weekend visits when the official residences were considered unsafe. Beatty and Ethel set up home at Hanover Lodge in Regent's Park, London.[9] The house had previously belonged to Admiral Sir Thomas John Cochrane and before him General Sir Robert Arbuthnot KCB.

The couple had two sons, David Field Beatty, 2nd Earl Beatty (1905–1972) born at the Capua Palace, Malta, and the Hon. Peter Randolph Louis Beatty (1910–1949). His marriage to a very wealthy heiress allowed Beatty an independence that most other officers lacked. She is reputed to have commented after he was threatened with disciplinary action following the straining of his ship's engines, "What? Court-martial my David? I'll buy them a new ship."[10] She had bought him a steam yacht, houses in London and in the Leicestershire hunting country, and a Scottish grouse moor. The couple circulated in high society, even occasionally dining with the King. However, there were disadvantages, as Beatty discovered after his marriage, for his wife was an unstable neurotic who caused him extreme mental tortures. Beatty was an intelligent and able leader, but all his social and sporting obligations, coupled with his high-strung temperament, prevented him from becoming a coldly calculating professional like Jellicoe – or his adversary, Hipper. Beatty’s flamboyant style included wearing a non-standard uniform, which had six buttons instead of the regulation eight on the jacket, and always wearing his cap at an angle.

Early career

In January 1884 Beatty passed into the officers' training ship Britannia tenth out of ninety-nine candidates.[11] During his two years at Britannia, moored at Dartmouth, Devon, he was given[clarification needed] twenty-five times for "minor offences" and beaten three times for more serious infractions. He passed out of Britannia eighteenth out of the thirty-three remaining cadets at the end of 1885.[11] Beatty's letters home made no complaint about the poor living conditions in Britannia, and generally he was extrovert, even aggressive, and resented discipline. However, he understood how far he could transgress without serious consequences, and this approach continued throughout his career.[12]

In January 1886, Beatty was given orders to join the China Station. The posting did not appeal to his mother, who wrote to Lord Charles Beresford, then a senior naval officer, member of parliament and personal friend, to use his influence to obtain something better.[13] Beatty was instead appointed to HMS Alexandra, flagship in the Mediterranean Squadron commanded by Admiral the Duke of Edinburgh's, Queen Victoria's second son.[14] This proved an excellent social opening for Beatty, who established a longstanding relationship with the Duke's eldest daughter, Marie, and with other members of the court. Alexandra was a three-masted sailing ship with auxiliary steam power, and despite remaining flagship was already outdated in a navy which was steadily transitioning from sail to steam. Life in the Mediterranean fleet was considerably easier than cadet life, with visits to friendly ports all around the Mediterranean, but Beatty was concerned to work diligently towards naval examinations, which would determine seniority and future promotion prospects.[15] Beatty was assigned as midshipman to assist lieutenant Stanley Colville during watchkeeping and Colville was to play an important part in Beatty's future career.[16]

In March 1889 Beatty left Alexandra. He spent three months from July to September 1889 on board Warspite for manoeuvres before joining the sailing corvette HMS Nile from 19 January 1892 to 23 June 1892 before returning to Britain.

From July to August 1892 he served in the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert while Queen Victoria was holidaying in the Mediterranean. Victoria was in mourning for her grandson, Albert Duke of Clarence, who died January 1892. Victoria would go ashore sometimes with full pomp and sometimes totally incognito. On leaving the ship he was promoted to Lieutenant on 25 August 1892.[19]

He rejoined HMS Ruby 31 August 1892, remaining in her until 5 September 1893. Ruby served in the South Atlantic and West Indies, so providing experience in handling a sailing ship in all conditions, but not in the new technologies of steam. From Ruby he transferred to the battleship Camperdown until October 1895. Camperdown had only recently been involved in the fleet accident where she rammed and sank HMS Victoria. Following Camperdown he was transferred to the battleship Trafalgar until 4 May 1896. Time spent in the battleships was little to Beatty's liking as the life involved no action but enormous efforts spent making the ships look smart at all times.

Sudan Campaign

Beatty gained recognition in the campaign for the recapture of the Sudan (1897–1899) commanded by Lord Kitchener. Stanley Colville was placed in command of the gunboats attached to the British expeditionary force in Egypt and as Beatty's former commander in Trafalgar and superior in 'Alexandra' he requested that Beatty join him. Control of the river Nile was considered vitally important for any expedition into Egypt and the Sudan. Beatty was seconded to the Egyptian government on 3 June 1896 and appointed second in command of the river flotilla. Colville was wounded during the operation, leaving Beatty in command of the gunboats for the successful attack on Dongola. The campaign halted at Dongola to regroup and Beatty returned to Britain on leave. He was commended by Kitchener for his part in the campaign and as a result was made Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).[20]

On 9 January 1897, he was given his first command, the destroyer Khartoum expedition. Overall naval commander was now Colin Keppel with other boats commanded by Horace Hood and Walter Cowan who were to remain friends and colleagues. Beatty first commanded the gunboat El Teb but this was capsized attempting to ascend the Fourth Cataract. Beatty then took command of Fateh between October 1897 and August 1898 when the gunboats were frequently in action advancing along the Nile ahead of the army. The gunboats were in support at the Battle of Omdurman, where Beatty made the acquaintance of Winston Churchill who had become a cavalry officer in Beatty's father's old regiment, the 4th Hussars, and had there learnt his family history. In a few hours 10,000 Dervishes were killed by rifle and machine gun fire without any of them getting within 600 yards of the British force.[21] This battle marked the effective end of resistance to the expeditionary force, but the gunboats were called into service to transport troops to Fashoda, 400 miles (640 km) south along the White Nile, where a small force of French troops had made a difficult land crossing and staked a claim to the area. The French were persuaded to withdraw without incident. Once again Kitchener commended Beatty for his efforts in the campaign and as a result Hood and Beatty were both promoted to Commander on 15 November 1898. At the time Beatty was 27 and had served only 6 years as Lieutenant compared to the typical 12 before promotion. He also acquired the Khartoum Medal and the Turkish Order of Mejidieh, fourth class.[22]

Beatty returned to England on leave where he met his future wife, Ethel Tree.

Boxer Rebellion

On 20 April 1899 Beatty was appointed executive officer of the small battleship HMS Barfleur, flagship of the China Station, Captain Stanley Colville under Rear-Admiral James Bruce. The first year of his tour of duty was uneventful, but unrest against foreign interlopers was growing in China. The Boxer movement was a secret Chinese peasant society committed to resisting oppression both from foreigners and from the Chinese government. The dowager empress Tzu-his partly encouraged the Boxer's opposition to foreigners in an attempt to turn their attention away from herself. The name was derived from ritual exercises supposed to make their users immune to bullets, which resembled boxing.[23]

In the summer of 1900 the rebellion reached Peking, where the German legation was attacked and foreign nationals withdrew to the relative safety of the Legation Quarter. Government troops joined forces with the rebels and the railway to the Treaty Port of Tientsin was interrupted. Admiral Sir Edward Seymour sent reinforcements to Peking, but they were insufficient to defend the Legation. An attempt was therefore made to send more troops from Tientsin, where British ships had been joined by French, German, Russian, Austrian, Italian and Japanese. The international naval brigade force of naval marines placed itself under the senior officer present, which was Seymour. After an urgent call for help from the Legation, Seymour set out on 10 June with 2000 troops to attempt to break through to Peking. The force got about half way before abandoning the attempt because the railway line had been torn up. By now rebels had begun destroying the track behind the force, cutting it off from Tientsin.[24]

On 11 June, Beatty and 150 men from Barfleur landed as part of a force of 2,400 defending Tientsin from 15,000 Chinese troops plus Boxers. On the 16th the Taku forts were bombarded and captured to ensure ships could still reach the port. Fierce fighting broke out throughout the foreign areas and railway station, and Beatty was injured by a bullet in the left arm and wrist. He was discharged from the field hospital after a few days, and took command of the British contingent of a relief force sent out to help Seymour. The survivors from Seymour's force, plus 200 wounded including John Jellicoe, were successfully brought back to Tientsin on the 26th. More soldiers were now arriving and three weeks later a force of 20,000 set off again to relieve Peking. Beatty was strongly commended by Captain E. H. Bayley, who had been his commander during the siege, and by the commander in chief. As a result Beatty was promoted to Captain on 9 November 1900, only two years after his promotion to Commander and aged only 29 rather than the average age of 43. Beatty returned to Britain, where he required an operation to restore proper use of his left arm.[25]

Advancement

In May 1902 he was passed fit for sea duty and was appointed captain of the cruiser HMS Juno in June, spending two months in exercises with the Channel Fleet under Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson before joining the Mediterranean fleet. Beatty worked hard to raise efficiency so that she was highly rated in gunnery and other competitions by the time he left the ship 19 December 1902. Ethel decided not to be left behind so rented the Capua Palace on Malta, home port of the Mediterranean Fleet, where she became part of the island's high society.[26]

Army Council from 1906 to 1908 where he was involved with drawing up plans for joint operations to land an expeditionary force in Europe.

He was made captain of the battleship HMS Queen on 15 December 1908 until replaced 4 January 1910. Queen was part of the Atlantic Fleet under Prince Louis of Battenberg. Beatty impressed Battenburg, who gave him excellent reports, but was critical of the lack of imagination and initiative shown in exercises, and of the general inexperience of all admirals in handling large fleets. He was promoted to Rear-Admiral on 1 January 1910 by a special order in council since he had not completed the requisite time as a captain. Just shy of 39, the youngest Admiral in the Royal Navy (except for Royal family members) since Horatio Nelson. Beatty's second son Peter was born April 1910.

Spring 1911 Beatty and family rented a house at Ryde on the Isle of Wight while he attended the senior officer's war course. Beatty considered it part interesting and part a waste of time. The issue of staff training was one of hot debate in the navy, with some such as Fisher seeing no point in more training, while others such as Beresford supported the development of a formal naval staff.

He was offered the post of second-in-command of the Atlantic Fleet, but declined it and asked for one in the Home Fleet. As the Atlantic Fleet post was a major command, the Admiralty were very unimpressed and his attitude nearly ruined his career. Beatty, as a rapidly promoted war hero, with no financial worries and with a degree of support in Royal circles, felt more confident than most naval officers in standing firm on requesting a posting nearer home. He was approaching two years on half pay (which would trigger automatic retirement from the navy) when on January 8, 1912 his career was saved by the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.[27] Churchill had met Beatty when Beatty was commander of a gunboat on the Nile supporting the army at the Battle of Omdurman, in which Churchill took part as a cavalry officer. A "probably apocryphal"[28] story relates that as Beatty walked into Churchill's office at the Admiralty, Churchill looked him over and said, "You seem very young to be an Admiral." Unfazed, Beatty replied, "And you seem very young to be First Lord." Churchill – who was himself only thirty-eight years old in 1912 – took to him immediately and he was appointed Private Naval Secretary to the First Lord against the advice of First Sea Lord Sir Arthur Wilson.[29]

On 1 March 1913 he received the appointment of Rear-Admiral Commanding the First Battle Cruiser Squadron.[30] Beatty was late taking up his new post, choosing not to cut short a holiday in Monte Carlo. On his eventual arrival, he set about drafting standing orders regarding how the squadron was to operate. He noted, 'Captains...to be successful must possess, in a marked degree, initiative, resource, determination, and no fear of accepting responsibility', and particularly regarding wartime conditions'...as a rule instructions will be of a very general character so as to avoid interfering with the judgement and initiative of captains...The admiral will rely on captains to use all the information at their disposal to grasp the situation quickly and anticipate his wishes, using their own discretion as to how to act in unforeseen circumstances..' The approach outlined by Beatty contradicted the views of many within the navy, who felt that ships should always be closely controlled by their commanding admiral, and harked back to reforms attempted by Admiral George Tryon. It is argued that Tryon had attempted to introduce greater independence and initiative amongst his captains, which he believed would be essential in the confusion of a real war situation, but had ironically been killed in an accident caused by captains rigorously obeying incorrect but precise orders issued by Tryon himself.[31]

A commander has some discretion as to choice of officers to serve under him. The new command came with a competent Flag Lieutenant, Charles Dix, but Beatty was not happy with him, and anyway the former commander of the squadron wanted Dix to accompany him to his new command. Beatty chose Lieutenant Ralph Seymour as his successor, despite Seymour being unknown to him. Seymour had aristocratic connections, which may have appealed to Beatty since he sought connections in society, but it was also the case that Seymour's sister was a longstanding close friend of Churchill's wife. Appointments by influence were common in the navy at this time, but the significance of Beatty's choice lay in Seymour's relative inexperience as a signals officer, which later resulted in difficulties in battle.[32]

World War I

On the eve of the First World War in 1914, Beatty was knighted with the KCB,[33] and promoted to acting Vice-Admiral a month later. In August 1915, he was promoted to full Vice-Admiral.[34] During the course of the war, he took part in actions at Heligoland Bight (1914), Dogger Bank (1915) and Jutland (1916). He was an aggressive commander who expected his subordinates to always use their initiative without direct orders from himself.

Jutland proved to be decisive in Beatty's career, despite the loss of two of his battlecruisers. Beatty is reported to have remarked (to his Flag Captain, Chatfield, later First Sea Lord in the early 1930s), "there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today," after two of them had exploded within half an hour during the battle. One theory is that this was caused by a design fault in the ammunition loading system to the main gun turrets, so that an enemy hit on the turret set off an explosion in the magazine, thus sinking the ship. Churchill's account of the First World War, The World Crisis, describes Beatty's next order as, "Steer two points nearer the enemy." His next order was to turn away by two points, and, in any case, a few minutes later he reversed his fleet's course to fulfill its anticipated role of leading the German forces towards the main British fleet.

Admiral John Jellicoe, described by Churchill as the only man who could "lose the war in an afternoon" by losing the strategic British superiority in dreadnought battleships, was not a dashing showman like David Beatty. When Jellicoe was promoted to First Sea Lord in 1916, Beatty succeeded him as commander-in-chief of the Grand Fleet and received promotion to the acting rank of Admiral at the age of 45 on 27 November.

Beatty received the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet in November 1918. On the night of 15 November, Rear-Admiral Hugo Meurer, the representative of Admiral Franz von Hipper, met Admiral Beatty aboard Beatty's flagship, HMS Queen Elizabeth. Beatty presented Meurer with the terms, which were expanded at a second meeting the following day. The U-boats were to surrender to Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt at Harwich, under the supervision of the Harwich Force, then the surface fleet was to sail to the Firth of Forth and surrender personally to Beatty. They would then be led to Scapa Flow and interned, pending the outcome of the peace negotiations. Meurer eventually signed the terms after midnight. Rather than show any sign of magnanimity to Meurer and his staff, he chose to overawe and humiliate them instead. Germany never forgot Beatty's treatment, and indeed, Germany chose to ignore the news of Beatty's subsequent death: this contrasting with the condolences and honours rendered by Germany at the news of Jellicoe's passing.

Postwar career

On 1 January 1919, Beatty was promoted to the permanent rank of Admiral, with seniority from 27 November 1916.[35] On 1 May, he was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet.[36] On 18 October, he was created 1st Earl Beatty, Viscount Borodale and Baron Beatty of the North Sea and Brooksby.[37] Afterwards, he served a lengthy term as First Sea Lord until 1927. This was not a happy period for the Royal Navy. With the removal of the German High Seas Fleet in 1919, Britain had no naval enemies, and at the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 it was agreed that the USA, Britain and Japan should set their navies in a ratio of 5:5:3, with France and Italy maintaining smaller fleets. Britain was required to scrap most of her vast First World War fleet (only two new, oddly-shaped, battleships, Rodney and Nelson were built at this time, known colloquially as the 'Cherry Tree Class' as they had been 'cut down by Washington'). Japan, which had been an ally of Britain since 1900, was angered that she had not been treated as an equal by the two major powers, and Anglo-Japanese relations soured thereafter. When the United States began to expand her navy in the 1930s, she would surpass Britain as the world's premier naval power.

After 1924 Beatty, supported by the First Lord of the Admiralty Bridgeman, clashed with the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill, over the number of cruisers required by the Royal Navy. At this stage of his career Churchill was opposed to what he saw as excessive defence spending. This may seem in odd in light of his previous and subsequent reputation, but in the 1920s no major war seemed to be on the horizon, although Beatty correctly warned that Japan should be treated as an enemy going forward. The dispute dragged on until after Beatty's retirement, and a further naval disarmament treaty, (the London Treaty of 1930) would limit the numbers of cruisers.

In 1927 Beatty, who had become the first chairman of the Chiefs of Staff, retired from active service. On the 24 July he was made a Freeman of Huddersfield.

Controversy

The battle of Jutland was the major naval engagement of the First World War and marked a turning point in the naval war. Although it was tactically inconclusive, with significantly higher losses in the British fleet but with the German fleet fleeing the field of battle, it was effectively a strategic defeat for Germany. The Royal Navy could much more readily replace its losses with ships already under construction, while the engagement ended with the German fleet retreating as fast as possible from the British. Thereafter the Imperial German Navy ceased any serious attempts to engage the British fleet and remained at home as a 'fleet in being'. British public perception of the engagement was initially as a serious defeat, at a time when popular opinion expected great things from the Royal Navy. As admiral in command, Jellicoe received much of the blame for this 'defeat', despite the fact that most of the significant losses were amongst the independent battlecruiser squadron commanded by Beatty.

A number of serious errors have been identified in Beatty's handling of this squadron. These included:

- Failing to engage the German battlecruiser squadron with all his ships, thus throwing away a two to one numerical superiority and instead fighting one-to-one. Beatty was given command of the 5th Battle Squadron to replace a squadron of battlecruisers away for training. These were four of the most powerful ships in the world, but he positioned them so far away from his six battlecruisers that they were unable to take part in most of the engagement with Admiral Hipper's squadron of five battlecruisers.[38]

- Failing to take advantage of the time available to him between sighting the enemy and the start of fighting, to position his battlecruisers to most effectively attack the enemy. At the point the German ships opened fire with accurately determined ranges for their guns, Beatty's ships were still maneuvering, some could not see the enemy because of their own smoke, and hardly any had the opportunity of a period of steady course as they approached to properly determine target range. As a result the German ships had a significant advantage in early hits, with obvious benefit. During this time he also lost the potential advantage of the larger guns on his ships: they could commence firing at a longer range than the German ships.[39]

- Failing to ensure that signals sent to his ships were handled properly and received by the intended ships. Lost signals added to the confusion and lost opportunities during the battle. This issue had already arisen in previous battles, where the same signals officer had been involved, but no changes had been made.[40]

- Failing in his role as fast armoured scout to report to Jellicoe the exact position of the German ships he encountered, or to keep in contact with the German fleet while he retreated to the main British Grand Fleet. This information was important to Jellicoe to know how best to position the main fleet to make the most of its eventual engagement with the German High seas fleet. Despite this, Jellicoe succeeded in positioning his ships to good advantage, relying on other closer cruisers for final knowledge of the German's position, but necessitating last-minute decisions.[41]

- The gunnery of his ships was generally poor compared to the rest of the fleet. This was partly a consequence of his ships being stationed at Rosyth, rather than Scapa Flow with the main fleet, since local facilities at Rosyth were limited, but this was a problem identified months before Jutland which Beatty had failed to correct.[42] He preferred to trust to rapid close-range fire rather than deliberate ranging and operating at extreme range, a failing which had also been pointed out to him previously. His battlecruisers achieved few hits on the enemy, with most of the damage being inflicted by the battleships when they eventually came close enough to take part.

After the war a report of the battle was prepared by the Admiralty under First Sea Lord Wemyss. Before the report was published, Beatty was himself appointed First Sea Lord, and immediately requested amendments to the report. When the authors refused to comply, he ordered it to be destroyed and instead had prepared an alternative report, which proved highly critical of Jellicoe. Considerable argument broke out as a result, with significant numbers of servicemen disputing the published version, including Admiral Bacon, who wrote his own book about the battle, criticising the version sponsored by Beatty and highly critical of Beatty's own part in the Battle.[43] Many books and reviews were published as the debate continued over which version of events was correct. Beatty was critical of Jellicoe's cautious approach to the Grand Fleet, arguing this had thrown away the opportunity for a decisive numerical victory. Defenders of Jellicoe argued that he did no more than protect the body of his fleet, which outnumbered the German ships while steadily pressing the attack. The German strategy was one which relied upon chance to create opportunities for local victories, such as had happened against Beatty, whereas Jellicoe considered a careful approach always favoured the larger force. Ultimately it was not clear that Jellicoe made any mistakes in his management of the fleet, nor departed from procedures which had been agreed upon by all concerned in advance.

Later life and legacy

David Beatty spent much of his life (when not at sea) in Leicestershire, and lived at Brooksby Hall and Dingley Hall. During the First World War, he and his wife performed many services for the public of Leicestershire, including opening up their home first as a VAD Hospital under the 5th Northern General Hospital, and later as a hospital for Naval Personnel.

In 1930 the Scottish artist Cowan Dobson painted a full-length portrait of Beatty in white-tie and tails.

A (perhaps apocryphal) story is sometimes told of Beatty's retirement, that he canvassed in uniform in support of Conservative candidates in dockyard constituencies, presumably in the 1929 or 1931 General Elections. On knocking on one door the lady of the house, presuming him to be a sailor in search of "horizontal refreshment", directed him to the local brothel several doors down the road. Another version of the story is that he canvassed with Nancy, Lady Astor, MP for Plymouth Sutton, and received an embarrassingly friendly welcome at boarding houses who were used to renting rooms by the hour to sailors and their lady companions.

Beatty died after catching a chill as pallbearer at the funeral of his old commander Admiral Jellicoe. He had been advised not to leave his bed, but he went anyway saying, "What will the Navy say if I fail to attend Jellicoe's funeral?" Beatty had requested in his will that he would like to be buried next to his wife Ethel at Dingley. Instead he was buried at St Paul's Cathedral. Thus the double grave at Dingley Church only has Beatty's wife buried there.[44]

In Germany, Beatty had ruined his reputation when he told the crews of his ships that were receiving the German High Seas Fleet for its internment at Scapa Flow, "Don't forget that the enemy is a despicable beast," and arranged the surrender of the German Fleet as a grand spectacle of humiliation. The German navy thus ignored Beatty's request that its Commander-in-Chief, Erich Raeder, attend his funeral – as Raeder had done at Jellicoe's funeral earlier. Raeder merely sent the German navy attache. Admiral Sir Dudley Pound commented: 'Who wants these sinkers-of-hospital-ships and machine-gunners-of-sailors-in-the-water at Admiral Beatty's funeral anyway?'.

The Royal Navy named a King George V-class battleship after Beatty, but this ship was renamed HMS Howe before completion, as another battleship of the same class, intended to be named after Jellicoe, was renamed HMS Anson. A public house in Motspur Park is named The Earl Beatty in his honour.

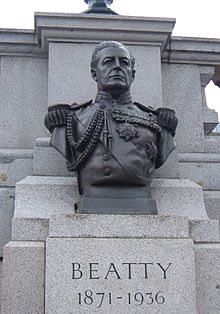

A bust of Beatty rests on Trafalgar Square in London, alongside those of Jellicoe and Andrew Cunningham, Admiral of the Fleet in World War II.

In Toronto, Canada at 55 Woodington Blvd. there is a school named Earl Beatty Junior and Senior Public School. The school belongs to the Toronto District School Board (commonly referred to as the TDSB). The school is an active member of the eastern Toronto community and celebrates his legacy.

A street called Beattytown was built in Galway, Ireland in the 1920s by the Irish Soldiers' and Sailors' Land Trust and named after Admiral Beatty, following their policy of naming streets after notable commanders of the British Empire.

In Singapore, a public school that was established in 1953, was named after Admiral Beatty. Beatty Secondary School adopted David Beatty's coat of arms, "Non Vi Sed Arte" and te colours as the official school colours.[45]

Styles

- 1871–1889: David Beatty

- 1889–1892: Sub-Lieutenant David Beatty

- 1892–1896: Lieutenant David Beatty

- 1896–1898: Lieutenant David Beatty, DSO

- 1898–1900: Commander David Beatty, DSO

- 1900–1905: Captain David Beatty, DSO

- 1905–1908: Captain David Beatty, MVO, DSO

- 1908–1910: Captain David Beatty, MVO, DSO, ADC

- 1910–1911: Rear-Admiral David Beatty, MVO, DSO

- 1911–19 June 1914: Rear-Admiral David Beatty, CB, MVO, DSO

- 19 June–September 1914: Rear-Admiral Sir David Beatty, KCB, MVO, DSO

- September 1914–1915: Rear-Admiral (Actg. Vice-Admiral) Sir David Beatty, KCB, MVO, DSO

- 1915–27 November 1916: Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty, KCB, KCVO, DSO

- 27 November 1916 – January 1917: Vice-Admiral (Actg. Admiral) Sir David Beatty, KCB, KCVO, DSO

- January–25 June 1917: Vice-Admiral (Actg. Admiral) Sir David Beatty, GCB, KCVO, DSO

- 25 June 1917 – 1 January 1919: Vice-Admiral (Actg. Admiral) Sir David Beatty, GCB, GCVO, DSO

- 1 January – 1 May 1919: Admiral Sir David Beatty, GCB, GCVO, DSO

- 1 May – 3 June 1919: Admiral of the Fleet Sir David Beatty, GCB, GCVO, DSO

- 3 June – 18 October 1919: Admiral of the Fleet Sir David Beatty, GCB, OM, GCVO, DSO

- 18 October 1919–1936: Admiral of the Fleet the Right Honourable the Earl Beatty, GCB, OM, GCVO, DSO

Honours and awards

British

- Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO)-17 November 1896[46]

- Member Fourth Class (present-day Lieutenant) of the Royal Victorian Order (MVO)-28 April 1905[47]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB)-January 1917 (Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB)-19 June 1914;[33] Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB)-19 June 1911[48])

- Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO)-25 June 1917[49] (Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO)-1915)

- Member of the Order of Merit (OM)-3 June 1919[50]

- Earl Beatty, Viscount Borodale of Wexford in the County of Wexford, Baron Beatty of the North Sea and of Brooksby in the County of Leicester-18 October 1919[37]

Foreign

- Order of Majid, 4th Class (Nishan-i-Majidieh) of the Ottoman Empire-1898[51]

- Order of St George, Fourth Class of the Russian Empire-1916[52]

- Grand Cross of the Legion d'Honneur of France-23 May 1919[53](Grand Officer-15 September 1916[54])

- Croix de Guerre of France-15 February 1919[55]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania of the Kingdom of Romania-17 March 1919[56]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer of the Kingdom of Greece-21 June 1919[57]

- Distinguished Service Medal (United States) 16 September 1919.[58]

Quotations

In the afternoon [of 1 June 1916] Beatty came into the Lion's chart-house. Tired and depressed, he sat down on the settee, and settling himself in a corner he closed his eyes. Unable to hide his disappointment at the result of the battle, he repeated in a weary voice, 'There is something wrong with our ships', then opening his eyes and looking at the writer, he added, 'And something wrong with our system'. Having thus unburdened himself he fell asleep.At 4.25, soon after we had resumed our position ahead of the Princess Royal, the third ship in the line, the Queen Mary (Captain Prowse) blew up exactly as had the Indefatigable. I was standing beside Sir David Beatty and we both turned round in time to see the unpleasant spectacle. The thought of my friends in her flashed through my mind; I thought also how lucky we had evidently been in the Lion. Beatty turned to me and said, "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships to-day," a remark which needed neither comment nor answer.References

- ^ Roskill. Beatty. p. 20. ISBN 0002162784.

- ^ Beatty, Charles (1980). Our Admiral, a biography of Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty. London: W. H. Allen. ISBN 049102388.

- ^ 'Our Admiral', p.4-5

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p. 20 citing letter to Beatty's wife

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p.11

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p.31

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p.31-35

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p.38

- ^ 'Our Admiral p.38-44

- ^ Massie. Castles of Steel. p. 89. ISBN 0679456716.

- ^ a b Roskill. Beatty. p. 21. ISBN 0002162784.

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p. 11-12

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p. 14

- ^ Roskill. Beatty. p. 22. ISBN 0002162784.

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p. 15, 21

- ^ 'Life and letters' p.12

- ^ Roskill. Beatty. p. 24. ISBN 0002162784.

- ^ Roskill p. 24 citing Shane Leslie draft biography of Beatty which was discontinued at the request of the family

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p. 22

- ^ Roskill p. 26-27, 29

- ^ 'Our Admiral' p. 29-30

- ^ Roskill p.27-29

- ^ Roskill p. 30

- ^ Roskill p. 31-32

- ^ Roskill p. 32-33

- ^ Roskill 40–41

- ^ Roskill p. 48-52

- ^ Massie. Castles of Steel. p. 92. ISBN 0679456716.

- ^ Gordon p. 381

- ^ Beatty Papers. I. p. 57.

- ^ Gordon p.381-382. For a rebuttal of Gordon's thesis on tactics in the late-nineteenth century Royal Navy see Allen, Matthew (July 2008). "The Deployment of Untried Technology: British Naval Tactics in the Ironclad Era". War in History 15 (3): pp. 269–293. doi:10.1177/0968344508091324.

- ^ Gordon p.384-385

- ^ a b London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ a b London Gazette

- ^ Brooks p. 232-234

- ^ Brooks p.234-240

- ^ Brooks p. 232-233, 237

- ^ Brooks

- ^ Brooks p.226-227

- ^ Reginald Bacon. The Jutland Scandal. Hutchinson & co..

- ^ Roskill. Beatty. p. 366. ISBN 0002162784.

- ^ http://www.beattysecondaryschool.net/cos/o.x?c=/wbn/pagetree&func=view&rid=46283

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31553. p. 11582. 16 September 1919. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

Further reading

- Bacon, Admiral Sir Reginald Hugh (1933). The Jutland Scandal. London: Hutchinson.

- Beatty, Admiral of the Fleet David, First Earl Beatty (1989). Ranft, Bryan McL.. ed. The Beatty Papers. Volume I. London: Navy Records Society. ISBN 0859678070.

- Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery at the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. London: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 0-714-65702-6.

- Chalmers, Rear-Admiral W. S. (1951). The Life and Letters of David, Earl Beatty. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Gordon, Andrew (1996). The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command. London: John Murray. ISBN 0719555337.

- Heathcote, T. A. (2002). British Admirals of the Fleet 1734–1995: A Biographical Dictionary. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-835-6.

- Ranft, Bryan McL. (1995). Murfett, Malcolm H.. ed. The First Sea Lords: From Fisher to Mountbatten. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-94231-7.

- Massie, Robert Kinloch (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-40878-0.

- Roskill, Captain Stephen Wentworth (1980). Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty – The Last Naval Hero: An Intimate Biography. London: Collins. ISBN 0-689-11119-3.

- Beatty, Charles (1980). Our Admiral, a biography of Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty. London: W. H. Allen. ISBN 049102388.

- "Royal Navy flag Officers service record, David Beatty". admirals.org. http://www.admirals.org.uk/admirals/fleet/beattyd.php. Retrieved 06 03 2010.

External links

Military offices Preceded by

Ernest TroubridgeNaval Secretary

1912–1913Succeeded by

Dudley de ChairPreceded by

The Lord Wester-WemyssFirst Sea Lord

1919–1927Succeeded by

Sir Charles MaddenAcademic offices Preceded by

Earl KitchenerRector of the University of Edinburgh

1917–1920Succeeded by

David Lloyd GeorgePeerage of the United Kingdom Preceded by

New CreationEarl Beatty

1919–1936Succeeded by

David Field BeattyCategories:- First Sea Lords

- Lords of the Admiralty

- Royal Navy admirals of the fleet

- Royal Navy personnel of the Mahdist War

- Royal Navy World War I admirals

- Earls in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- Rectors of the University of Edinburgh

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Recipients of the Order of St. George

- Recipients of the Order of the Medjidieh

- Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France)

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Star of Romania

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Redeemer

- People educated at Kilkenny College

- 1871 births

- 1936 deaths

- Royal Navy personnel of the Boxer Rebellion

- Foreign recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.