- Triple Goddess (Neopaganism)

-

- This article discusses the "Maiden, Mother, Crone" goddess triad of certain forms of Neopaganism. See triple goddesses for other uses.

The Triple Goddess is the subject of much of the writing of Robert Graves, and has been adopted by some neopagans as one of their primary deities. The term triple goddess is sometimes used outside of Neopaganism to refer to historical goddess triads and single goddesses of three forms or aspects. In common Neopagan usage the three female figures are frequently described as the Maiden, the Mother, and the Crone, each of which symbolises both a separate stage in the female life cycle and a phase of the moon, and often rules one of the realms of earth, underworld, and the heavens. These may or may not be perceived as aspects of a greater single divinity. The feminine part of Wicca's duotheistic theological system is sometimes portrayed as a Triple Goddess, her masculine counterpart being the Horned God. Many other neopagan belief systems follow Graves in his use of the figure of the Triple Goddess, and it continues to be an influence on feminism, literature, Jungian psychology and literary criticism.

Contents

Origins

Ronald Hutton, a scholar of neopaganism, argues that the concept of the triple moon goddess as Maiden, Mother, and Crone, each facet corresponding to a phase of the moon, is a modern creation of Robert Graves, drawing on the work of 19th and 20th century scholars such as especially Jane Harrison; and also Margaret Murray, James Frazer, the other members of the "myth and ritual" school or Cambridge Ritualists, and the occultist and writer Aleister Crowley.[1] The Triple Goddess was here distinguished by Hutton from the prehistoric Great Mother Goddess, as described by Marija Gimbutas and others, whose worship in ancient times he regarded as neither proven nor disproven [2] Nor did Hutton dispute that in ancient pagan worship "partnerships of three divine women" occurred; rather he proposes that Jane Harrison looked to such partnerships to help explain how ancient goddesses could be both virgin and mother (the third person of the triad being as yet unnamed). Here she was according to Hutton "extending" the ideas of the prominent archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans who in excavating Knossos in Crete had come to the view that prehistoric Cretans had worshipped a single mighty goddess at once virgin and mother. In Hutton's view Evans' opinion owed an "unmistakable debt" to the Christian belief in the Virgin Mary.[3]

Robert Graves

According to Ronald Hutton, the concept of a Triple Goddess with Maiden, Mother and Crone aspects and lunar symbology was Robert Graves's contribution to modern paganism. [4] According to Hutton, Graves, in his The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (1948), took Harrison's idea of goddess-worshipping matriarchal early Europe[5][6] and the imagery of three aspects, and related these to the Triple Goddess. [7]

Graves wrote extensively on the subject of the Triple Goddess who he saw as the Muse of all true poetry in both ancient and modern literature. [8] He thought that her ancient worship underlay much of classical Greek myth although reflected there in a more or less distorted or incomplete form. As an example of an unusually complete survival of the "ancient triad" he cites from the classical source Pausanias the worship of Hera in three persons as girl, wife, and widow.[9] Other examples he gives include the goddess triad Moira Ilythia and Callone ("Death, Birth and Beauty") from Plato's Symposium [10] ; the triple goddess Hecate; the story of the rape of Kore, (the triad here Graves said to be Kore, Persephone and Hecate with Demeter the general name of the goddess); alongside a large number of other configurations. [11] A figure he used from outside of Greek myth was of the Akan Triple Moon Goddess Ngame, who Graves said was still worshipped in 1960. [12]

Graves states that his Triple Goddess is the Great Goddess "in her poetic or incantatory character", and that the goddess in her ancient form took the gods of the waxing and waning year successively as her lovers.[13] Graves believed that the Triple Goddess was an aboriginal deity also of Britain, and that traces of her worship survived in early modern British witchcraft and in various modern British cultural attitudes such as what Graves believed to be a preference for a female sovereign.[14]

Graves regarded "true poetry" as inspired by the Triple Goddess, as an example of her continuing influence in English poetry he instances the "Garland of Laurell" by the English poet, John Skelton (c.1460-1529) — Diana in the leavës green, Luna that so bright doth sheen, Persephone in Hell. — as evoking his Triple Goddess in her three realms of earth, sky and underworld.[15]

In the anthology The Greek Myths (1955), Graves systematically applied his convictions enshrined in The White Goddess to Greek mythology, exposing a large number of readers to his various theories concerning goddess worship in ancient Greece.[16] Graves posited that Greece had been settled by a matriarchal goddess worshipping people before being invaded by successive waves of patriarchal Indo-European speakers from the north. Much of Greek myth in his view recorded the consequent religious political and social accommodations until the final triumph of patriarchy. Graves did not invent this picture but drew from nineteenth and early twentieth century scholarship. This account has not been disproved but alternative explanations have emerged and is not accepted as a consensus view. [17] The twentieth century archeologist Marija Gimbutas (see below) also argued for a triple goddess-worshipping European neolithic modified and eventually overwhelmed by waves of partiarchal invaders although she saw this neolithic civilization as egalitarian and "matristic" rather than "matriarchal" in the sense of gynocratic. [18]

While Graves's work has encountered much criticism in academic literature (see The White Goddess#Criticism and The Greek Myths#Reception), it continues to have a lasting influence on many areas of Neopaganism.[6]

Jane Ellen Harrison

In her discussion of James Mellaart's theories regarding Çatalhöyük, Lynn Meskell says it is probable that the Triple Goddess originated[19] with the work of Jane Ellen Harrison.[20] Harrison asserts the existence of female trinities, discusses the Horae as chronological symbols representing the phases of the Moon and goes on to equate the Horae with the Seasons, the Graces and the Fates.[21] and the three seasons of the ancient Greek year,[22] and notes that "[T]he matriarchal goddess may well have reflected the three stages of a woman's life."[23]

Ronald Hutton writes:

[Harrison's] work, both celebrated and controversial, posited the previous existence of a peaceful and intensely creative woman-centred civilization, in which humans, living in harmony with nature and their own emotions, worshipped a single female deity. The deity was regarded as representing the earth, and as having three aspects, of which the first two were Maiden and Mother; she did not name the third. ... Following her work, the idea of a matristic early Europe which had venerated such a deity was developed in books by amateur scholars such as Robert Briffault's The Mothers (1927) and Robert Graves's The White Goddess (1946).[5]

John Michael Greer writes:

Harrison proclaimed that Europe itself had been the location of an idyllic, goddess-worshipping, matriarchal civilization just before the beginning of recorded history, and spoke bitterly of the disastrous consequences of the Indo-European invasion that destroyed it. In the hands of later writers such as Robert Graves, Jacquetta Hawkes, and Marija Gimbutas, this 'lost civilisation of the goddess' came to play the same sort of role in many modern Pagan communities as Atlantis and Lemuria did in Theosophy.[6]

The "myth and ritual" school or Cambridge Ritualists, of which Harrison was a key figure, while controversial in its day, is now considered passé in intellectual and academic terms. According to Robert Ackerman, "[T]he reason the Ritualists have fallen into disfavor... is not that their assertions have been controverted by new information. ... Ritualism has been swept away not by an access of new facts but of new theories."[24]

Ronald Hutton wrote on the decline the "Great Goddess" theory specifically : "The effect upon professional prehistorians was to make most return, quietly and without controversy, to that careful agnosticism as to the nature of ancient religion which most had preserved until the 1940s. There had been no absolute disproof of the veneration of a Great Goddess, only a demonstration that the evidence concerned admitted of alternative explanations."[25]

Marija Gimbutas

The theories of Marija Gimbutas on the Chalcolithic, a period she defined as "Old Europe" (6500-3500 BCE) [26] have been widely adopted by New Age and ecofeminist groups.[27] (She was dubbed "Grandmother of the Goddess Movement" in the 1990s.[28]) Gimbutas postulated that in ancient Europe, the Aegean and the Near East, a great Triple Goddess was worshipped, predating the patriarchal religions imported by nomadic speakers of Indo-European languages (later superseded by a patriarchal monotheism). Gimbutas interpreted iconography from neolithic and earlier periods of European history evidence of worship of a triple goddess represented by:

- "stiff nudes", birds of prey or poisonous snakes interpreted as "death"

- mother-figures interpreted as symbols of "birth and fertility"

- moths, butterflies or bees, or alternatively a symbols such as a frog, hedgehog or bulls head which she interpreted as being the uterus or fetus, as being symbols of "regeneration" [29]

The first and third aspects of the goddess, according to Gimbutas, were frequently conflated to make a goddess of death-and-regeneration represented in folklore by such figures as Baba Yaga. Gimbutas regarded the Eleusinian Mysteries as a survival into classical antiquity of this ancient goddess worship,[30] a suggestion which Georg Luck echos.[31]

Gimbutas's work has been criticised as mistaken on the grounds of dating, archeological context and typologies[27] with most archeologists considering her goddess hypothesis implausible [32] and her work has been called pseudo-scholarship.[33] This has been echoed by feminist authors such as Cynthia Eller[34] and religion writers such as Philip G. Davis.[35] Linguist M. L. West has called Gimbutas's goddess-based "Old European" religion being overtaken by a patriarchal Indo-European one "essentially sound".[36] Her histories have been seen as a poetic projection of her personal life onto history hidden behind a facade of positivistic "explanation", with her goddess-orientated society being based on her childhood and adolescence.[37]

Contemporary beliefs and practices

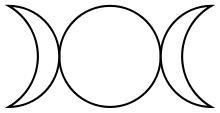

"Triple Goddess" symbol of waxing, full and waning moon, representing the aspects of Maiden, Mother, and Crone.[38]

"Triple Goddess" symbol of waxing, full and waning moon, representing the aspects of Maiden, Mother, and Crone.[38]

While many Neopagans are not Wiccan, and within Neopaganism the practices and theology vary widely,[39] many Wiccans and other neopagans worship the "Triple Goddess" of maiden, mother, and crone, a practice going back to mid-twentieth-century England. In their view, sexuality, pregnancy, breastfeeding — and other female reproductive processes — are ways that women may embody the Goddess, making the physical body sacred.[40]

- The Maiden represents enchantment, inception, expansion, the promise of new beginnings, birth, youth and youthful enthusiasm, represented by the waxing moon.

- The Mother represents ripeness, fertility, sexuality, fulfillment, stability, power and life represented by the full moon.

- The Crone represents wisdom, repose, death, and endings represented by the waning moon.

Helen Berger writes that "according to believers, this echoing of women's life stages allowed women to identify with deity in a way that had not been possible since the advent of patriarchal religions."[41] The Church of All Worlds is one example of a neopagan organisation which identifies the Triple Goddess as symbolizing a "fertility cycle".[42] This model is also supposed to encompass a personification of all the characteristics and potential of every woman who has ever existed.[43] Other beliefs held by worshippers, such as Wiccan author D. J. Conway, include that reconnection with the Great Goddess is vital to the health of humankind "on all levels". The Goddess is seen to stand for unity, cooperation, and participation with all creation, while in contrast male gods represent dissociation, separation and dominion of nature.[44] These views have been criticised by members of both the neopagan and scholarly communities as re-affirming gender stereotypes and symbolically being unable to adequately face humanity's current ethical and environmental situation.[45]

D. J. Conway includes a trinity of the Greek goddesses Demeter, Kore-Persephone, and Hecate, in her discussion of the Maiden-Mother-Crone archetype.[46]

Dianic Wicca

The Dianic tradition adopted Graves's Triple Goddess, along with other elements from Wicca, and is named after the Roman goddess Diana, the goddess of the witches in Charles Godfrey Leland's 1899 book Aradia.[47][48] Zsuzsanna Budapest, widely considered the founder of Dianic Wicca,[49] considers her Goddess "the original Holy Trinity; Virgin, Mother, and Crone."[50] Dianic Wiccans such as Ruth Barrett, follower of Budapest and co-founder of the Temple of Diana, use the Triple Goddess in ritual work and correspond the "special directions" of "above", "center", and "below" to Maiden, Mother, and Crone respectively.[51] Barrett says "Dianics honor She who has been called by Her daughters throughout time, in many places, and by many names." [48]

Triple-Goddess Stone

Main article: Natib Qadish (Neopagan religion)Qudshu-Astarte-Anat is a representation of a single goddess who is a combination of three goddesses: Qetesh (Athirat), Astarte, and Anat. It was a common practice for Canaanites and Egyptians to merge different deities through a process of synchronization, thereby, turning them into one single entity. The "Triple-Goddess Stone", that was once owned by Winchester College, shows the goddess Qetesh with the inscription "Qudshu-Astarte-Anat", showing their association as being one goddess, and Qetesh (Qudshu) in place of Athirat. The "Triple-Goddess Stone" is sacred to Qadishuma, and the Natib Qadish religion.

Religious scholar Saul M. Olyan (author of Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel), calls the representation on the Qudshu-Astarte-Anat plaque "a triple-fusion hypostasis", and considers Qudshu to be an epithet of Athirat by a process of elimination, for Astarte and Anat appear after Qudshu in the inscription.[52][53]

Neopagan archetype theory

Some neopagans assert that the worship of the Triple Goddess dates to pre-Christian Europe and possibly goes as far back as the Paleolithic period and consequently claim that their religion is a surviving remnant of ancient beliefs. They believe the Triple Goddess is an archetypal figure which appears in various different cultures throughout human history, and that many individual goddesses can be interpreted as Triple Goddesses,[43] The wide acceptance of an archetype theory has led to neopagans adopting the images and names of culturally divergent deities for ritual purposes;[54] for instance, Conway,[55] and goddess feminist artist Monica Sjöö,[56] connect the Triple Goddess to the Hindu Tridevi (literally "three goddesses") of Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Parvati (Kali/Durga).

Jungian psychology

Several advocates of Wicca, such as Vivianne Crowley and Selena Fox, are practising psychologists or psychotherapists, and the work of Jung has had a large influence on their work.[57] Wouter J. Hanegraaff comments that Crowley's works can give the impression that Wicca is little more than a religious and ritual translation of Jungian psychology.[58]

The Triple Goddess as an archetype is discussed in the works of Carl Jung and Carl Kerényi,[59] and the later works of their follower, Erich Neumann.[60] Jung considered the general arrangement of deities in triads as a pattern which arises at the most primitive level of human mental development and culture.[61]

In 1949 Jung and Kerényi theorised that groups of three goddesses found in Greece become quaternities only by association with a male god. They give the example of Diana only becoming three (Daughter, Wife, Mother) through her relationship to Zeus, the male deity. They go on to state that different cultures and groups associate different numbers and cosmological bodies with gender.[62] "The threefold division [of the year] is inextricably bound up with the primitive form of the goddess Demeter, who was also Hecate, and Hecate could claim to be mistress of the three realms. In addition, her relations to the moon, the corn, and the realm of the dead are three fundamental traits in her nature. The goddess's sacred number is the special number of the underworld: '3' dominates the chthonic cults of antiquity."[63]

Karl Kerenyi, wrote in 1952 that several Greek goddesses were triple moon goddesses of the Maiden Mother Crone type, including Hera and others. [64]

In discussing examples of his Great Mother archetype, Neumann mentions the Fates as "the threefold form of the Great Mother",[65] details that "the reason for their appearance in threes or nines, or more seldom in twelves, is to be sought in the threefold articulation underlying all created things; but here it refers most particularly to the three temporal stages of all growth (beginning-middle-end, birth-life-death, past-present-future)."[66] Andrew Von Hendy claims that Neumann's theories are based on circular reasoning, whereby a Eurocentric view of world mythology is used as evidence for a universal model of individual psychological development which mirrors a sociocultural evolutionary model derived from European mythology.[67]

Valerie H. Mantecon follows Annis V. Pratt that the Triple Goddess of Maiden, Mother and Crone is a male invention that both arises from and biases an androcentric view of femininity, and as such the symbolism is often devoid of real meaning or use in depth-psychology for women.[68] Mantecon suggests that a feminist re-visioning of the Crone symbolism away from its usual associations with "death" and towards "wisdom" can be useful in women transitioning to the menopausal phase of life and that the sense of history that comes from working with mythological symbols adds a sense of meaning to the experience.[69]

Goddess Feminism and social critique

The figure of the Triple Goddess is used by goddess feminists to critique societies' roles and treatment of women. Literary critic Jeanne Roberts sees a rejection of the "Crone" figure by Christians in the Middle Ages as a root cause of the alleged persecuting of witches.[70] Fantasy and science-fiction author Ursula Le Guin comments that the lack of acceptance of change for women (exemplified by the youth and beauty myth) in contemporary society has led to an erasure of the Triple Goddess, into a single, Marilyn Monroe-faced goddess.[71]

According to Goddess Feminist Barbara G. Walker various supernatural female triads like the Gallo/Germano-Roman Matres and Matrones (frequently depicted in trios),[72] the Greco-Roman Erinyes or Furies, or the Morrígan to whome she applies the Maiden Mother Crone model.[73]

Fiction, film and literary criticism

Author Margaret Atwood recalls reading Graves's The White Goddess at the age of 19. Atwood describes Graves' concept of the Triple Goddess as employing violent and misandric imagery, and says the restrictive role this model places on creative women. Atwood says that it put her off from being a writer.[74] Atwood's work has been noted as containing Triple Goddess motifs who sometimes appear failed and parodic.[75] Atwood's Lady Oracle has been cited as a deliberate parody of the Triple Goddess, which subverts the figure and ultimately liberates the lead female character from the oppressive model of feminine creativity that Graves constructed.[76]

Literary critic Andrew D. Radford, discussing the symbolism of Thomas Hardy's 1891 novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles, in terms of Myth sees the Maiden and Mother as two phases of the female lifecycle through which Tess passes, whilst the Crone phase, Tess adopts as a disguise which prepares her for harrowing experiences .[77]

The concept of the triple goddess has been applied to a feminist reading of Shakespeare.[78][79]

Thomas DeQuincey developed a female trinity, Our Lady of Tears, the Lady of Sighs and Our Lady of Darkness, in Suspiria De Profundis, which has been likened to Graves's Triple Goddess but stamped with DeQuincey's own melancholy sensibility.[80]

The triple goddess is referenced in Marion Zimmer Bradley's book "The Mists of Avalon."

According to scholar Juliette Wood, modern fantasy fiction plays a large part in the conceptual landscape of the neo-pagan world.[81] The three supernatural female figures called variously the Ladies, Mother of the Camenae, the Kindly Ones, and a number of other different names in The Sandman comic books by Neil Gaiman, merge the figures of the Fates and the Maiden-Mother-Crone goddess.[82] In Alan Garner's The Owl Service, based on the fourth branch of the Mabinogion and influenced by Robert Graves, clearly delineates the character of the Triple Goddess. Garner goes further, in his other novels making every female character intentionally represent an aspect of the Triple Goddess.[83] In George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series, the Maid, the Mother, and the Crone are three aspects of the septune deity in the Faith of the Seven.

The figure of the Triple Goddess has also been used in film criticism. Norman Holland has used Jungian criticism to explore the female characters in Alfred Hitchcock's film Vertigo using Graves's Triple Goddess motif as a reference.[84] Roz Kaveney sees the main characters in James Cameron's movie Aliens as reflecting aspects of the triple goddess: The Alien Queen (Crone), Ripley (Mother) and Newt (Maiden).[85]

One of the most popular songs performed by the American heavy metal band The Sword is, "Maiden, Mother & Crone", with lyrics describing an encounter with the Triple Goddess. It was featured on their album Gods of the Earth. The official video prominently features the three aspects of the goddess and a waxing, full, and waning moon.[86]

A book written by Michael J Scott called The Alchemyst features a character known as Hekate. She is personified as a woman who changes age through the cycle of the day, starting in the morning as a girl, then aging to an adult woman, and finally becoming an old woman as the day draws to a close before dying and being reborn at the beginning of the next day. Each day she would start the cycle anew.

See also

References

- ^ Triumph of the Moon, p. 41.

- ^ Triumph of the Moon, p. 355-357

- ^ Triumph of the Moon, p.36-37

- ^ The Myth and Ritual School: J.G. Frazer and the Cambridge Ritualists. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93963-1, ISBN 978-0-415-93963-8.

Hutton, Ronald (1997). "The Neolithic Great Goddess: A Study in Modern Tradition" from Antiquity, March 1997. - ^ a b Hutton, Ronald (1997). "The Neolithic Great Goddess: A Study in Modern Tradition" from Antiquity, March 1997. p.3 (online copy).

- ^ a b c Greer, John Michael (2003). The New Encyclopedia of the Occult. Llewellyn. p. 280. ISBN 9781567183368. http://books.google.com/books?id=xAmMNnJlfnoC&lpg=PP280&pg=PA280#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ Miranda Seymour, Robert Graves: life on the edge, p. 307

- ^ The White Goddess Chapter One "Poets and Gleemen"

- ^ The White Goddess, Amended and Enlarged Edition, 1961, Chapter 21, "The Waters of Styx" page 368 , Also "The Greek Myths" in several places.

- ^ White Goddess,Amended and Enlarged Edition, 1961, Foreword, page 11

- ^ The Greek Myths, single edition, 1992, Penguin

- ^ White Goddess, Chapter 27, Postcript 1960,

- ^ Harvey, Graham. Introduction to "The Triple Muse", p. 129, in Clifton, Chas, and Harvey, Graham (eds.) (2004). The Paganism Reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30352-4, ISBN 978-0-415-30352-1.

- ^ Graves, Robert. "The Triple Muse", p.148, in Clifton, Chas, and Harvey, Graham (eds.) (2004). The Paganism Reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30352-4, ISBN 978-0-415-30352-1.

- ^ Graves, Robert (1948). The White Goddess: a Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth. p.377.

- ^ Von Hendy, Andrew (2002). The Modern Construction of Myth, 2nd edition. Indiana University Press. p.354. ISBN 0-253-33996-0, ISBN 978-0-253-33996-6.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1997). "The Neolithic Great Goddess: A Study in Modern Tradition" from Antiquity, March 1997. p.7 (online). See also relevant wikipedia articles, Dorian invasion, Mycanean Age Greek Dark Ages

- ^ "Civilization of the Goddess" Marija Gimbutas

- ^ Meskell, Lynn (1999). "Feminism, Paganism, Pluralism", p.87, in Gazin-Schwartz, Amy, and Holtorf, Cornelius (eds.) (1999). Archaeology and Folklore. Routledge. "It seems clear that the initial recording of Çatalhöyük [1961-1965] was largely influenced by decidedly Greek notions of ritual and magic, especially that of the Triple Goddess — maiden, mother, and crone. These ideas were common to many at that time, but probably originated with Jane Ellen Harrison, Classical archaeologist and member of the famous Cambridge Ritualists (Harrison 1903)." ISBN 0-415-20144-6, ISBN 978-0-415-20144-5.

See also: Hutton, Ronald (2001). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press. pp.36-37: "In 1903... an influential Cambridge classicist, Jane Ellen Harrison, declared her belief in [a Great Earth Mother] but with a threefold division of aspect. ... [S]he pointed out that the pagan ancient world had sometimes believed in partnerships of three divine women, such as the Fates or the Graces. She argued that the original single one, representing the earth, had likewise been honoured in three roles. The most important of these were the Maiden, ruling the living, and Mother, ruling the underworld; she did not name the third. ... [S]he declared that all male deities had originally been subordinate to the goddess as her lovers and her sons." ISBN 0-19-285449-6, ISBN 978-0-19-285449-0. - ^ Harrison, Jane Ellen (1903). Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p.286ff. Excerpts: "... Greek religion has... a number of triple forms, Women-Trinities.... First it should be noted that the trinity-form was confined to the women goddesses. ... of a male trinity we find no trace. ... The ancient threefold goddesses...."

— (1912). Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— (1913). Ancient Art and Ritual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - ^ Harrison, Jane Ellen (1912). Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp.189-192: "The three Horae are the three phases of the Moon, the Moon waxing, full, and waning. ... [T]he Moon is the true mother of the triple Horae, who are themselves Moirae, and the Moirae, as Orpheus tells us, are but the three moirae or divisions (μέρη) of the Moon herself, the three divisions of the old year. And these three Moirae or Horae are also Charites."

- ^ Harrison, Jane Ellen (1903). Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p.288.

- ^ Harrison, Jane Ellen (1903). Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p.317.

- ^ Ackerman, Robert (2002). The Myth and Ritual School: J.G. Frazer and the Cambridge Ritualists. Routledge. p.188. ISBN 0-415-93963-1, ISBN 978-0-415-93963-8.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1997). "The Neolithic Great Goddess: A Study in Modern Tradition" from Antiquity, March 1997. p.7 (online).

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (1974). The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, 7000-3500 B.C.: Myths, Legends and Cult Images. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05014-7, ISBN 978-0-500-05014-9.

— (1999). The Living Goddesses. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21393-9, ISBN 978-0-520-21393-7. - ^ a b Gilchrist, Roberta (1999). Gender and Archaeology: Contesting the Past. Routledge. p.25. ISBN 0-415-21599-4, ISBN 978-0-415-21599-2.

- ^ Talalay, Lauren E. (1999). (Review of) The Living Goddesses in Bryn Mawr Classical Review 1999-10-05.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (1991). The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe. HarperSanFrancisco. p.223. ISBN 0-06-250368-5, ISBN 978-0-06-250368-8.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (1991). The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe, HarperSanFrancisco. p.243, and whole chapter "Religion of the Goddess". ISBN 0-06-250368-5, ISBN 978-0-06-250368-8.

- ^ Luck, Georg (1985). Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Collection of Ancient Texts. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2548-2, ISBN 978-0-8018-2548-4. p.5 suggests that this goddess persisted into Classical times as Gaia (the Greek Earth Mother), and the Roman Magna Mater, among others.

- ^ Whitehouse, Ruth (2006). "Gender Archaeology in Europe", p.756, in Nelson, Sarah Milledge (ed.) (2006). Handbook of Gender in Archaeology. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0-7591-0678-9, ISBN 978-0-7591-0678-9.

- ^ Dever, William G. (2005) Did God Have A Wife?: Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p.307. ISBN 0-8028-2852-3, ISBN 978-0-8028-2852-1.

- ^ Eller, Cynthia P. (2001). The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won't Give Women a Future. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-6793-8, ISBN 978-0-8070-6793-2.

- ^ Davis, Philip G. (1998). Goddess Unmasked: The Rise of Neopagan Feminist Spirituality. Spence Publishing Company. ISBN 0-9653208-9-8, ISBN 978-0-9653208-9-4.

- ^ West, Martin Litchfield (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. p.140. ISBN 0-19-928075-4, ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

- ^ Chapman, John (1998). "A Biographical Sketch of Marija Gimbutas" in Margarita Díaz-Andreu García, Marie Louise Stig Sørensen (eds.) (1998). Excavating Women: A History of Women in European Archaeology. Routledge. pp.299-301. ISBN 0-415-15760-9, ISBN 978-0-415-15760-5.

- ^ Gilligan, Stephen G., and Simon, Dvorah (2004). Walking in Two Worlds: The Relational Self in Theory, Practice, and Community. Zeig Tucker & Theisen Publishers. p.148. ISBN 1-932462-11-2, ISBN 978-1-932462-11-1.

- ^ Adler, Margot (1979, revised 2006). Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-303819-2, ISBN 978-0-14-303819-1.

- ^ Pike, Sarah M. (2007). "Gender in New Religions" in Bromley, David G. (ed.)(2007) Teaching New Religious Movements. Oxford University Press US. p.214. ISBN 0-19-517729-0, ISBN 978-0-19-517729-9.

- ^ Berger, Helen A. (2006). Witchcraft and Magic: Contemporary North America. University of Pennsylvania Press. p.62. ISBN 0-8122-1971-6, ISBN 978-0-8122-1971-5.

- ^ Zell, Otter and Morning Glory. "Who on Earth is the Goddess?" (accessed 2009-10-03)

- ^ a b Reid-Bowen, Paul. Goddess as Nature: Towards a Philosophical Thealogy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p.67. ISBN 0-7546-5627-6, ISBN 978-0-7546-5627-2.

- ^ Conway, Deanna J. (1995). Maiden, Mother, Crone: The Myth and Reality of the Triple Goddess. Llewellyn. ISBN 0-87542-171-7, ISBN 978-0-87542-171-1.

- ^ Devlin-Glass, Frances, and McCredden, Lyn (2001). Feminist Poetics of the Sacred: Creative Suspicions. Oxford University Press. pp.39-42. ISBN 0-19-514469-4, ISBN 978-0-19-514469-7.

- ^ Conway, Deanna J. (1995). Maiden, Mother, Crone: the Myth and Reality of the Triple Goddess. Llewellyn. p.54. ISBN 0-87542-171-7, ISBN 978-0-87542-171-1.

Cf. Smith, William (1849). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, v.2, p.364, Hecate: "... being as it were the queen of all nature, we find her identified with Demeter...; and as a goddess of the moon, she is regarded as the mystic Persephone."

See also Encyclopedia Britannica (1911, online): Hecate: "As a chthonian power, she is worshipped at the Samothracian mysteries, and is closely connected with Demeter." Proserpine: "She was sometimes identified with Hecate." - ^ Berger, Helen A. (2006). Witchcraft and Magic: Contemporary North America. University of Pennsylvania Press. p.61. ISBN 0-8122-1971-6, ISBN 978-0-8122-1971-5.

- ^ a b Barrett, Ruth (2004). The Dianic Wiccan Tradition.

- ^ Barrett, Ruth (2007). Women's Rites, Women's Mysteries: Intuitive Ritual Creation. Llewellyn. p.xviii. ISBN 0-7387-0924-7, ISBN 978-0-7387-0924-6.

- ^ http://wicca.dianic-wicca.com/ (accessed 2009-10-03)."

- ^ Barrett, Ruth (2007). Women's Rites, Women's Mysteries: Intuitive Ritual Creation. Llewellyn. p.123. ISBN 0-7387-0924-7, ISBN 978-0-7387-0924-6.

- ^ The Ugaritic Baal cycle: Volume 2 by Mark S. Smith - Page 295

- ^ The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts by Mark S. Smith - Page 237

- ^ Rountree, Kathryn (2004). Embracing the Witch and the Goddess: Feminist Ritual-Makers In New Zealand. Routledge. p.46. ISBN 0-415-30360-5, ISBN 978-0-415-30360-6.

- ^ Conway, Deanna J. (1995). Moon Magick: Myth & Magick, Crafts & Recipes, Rituals & Spells. Llewellyn. p.230: "Nov. 27: Day of Parvati-Devi, the Triple Goddess who divided herself into Sarasvati, Lakshmi, and Kali, or the Three Mothers." ISBN 1-56718-167-8, ISBN 978-1-56718-167-8.

- ^ Sjöö, Monica (1992). New Age and Armageddon: the Goddess or the Gurus? - Towards a Feminist Vision of the Future. Women's Press. p.152: "They were white Sarasvati, the red Lakshmi and black Parvati or Kali/Durga - the most ancient triple Goddess of the moon." ISBN 0-7043-4263-4, ISBN 978-0-7043-4263-7.

- ^ Morris, Brian (2006). Religion and Anthropology: a Critical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p.286. ISBN 0-521-85241-2, ISBN 978-0-521-85241-8.

- ^ Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1996). New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. Brill, Leiden. p.90. ISBN 90-04-10696-0, ISBN 978-90-04-10696-3.

- ^ Jung, C. G., and Kerényi, C. (1949). Essays on a Science of Mythology: the Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. Pantheon Books.

- ^ Neumann, Erich (1955). The Great Mother: an Analysis of the Archetype. Pantheon Books.

- ^ Jung, Carl Gustav (1942). "A Psychological Approach to the Dogma of the Trinity" (essay), in Collected Works : Psychology and Religion: West and East, Volume 11 (2nd edition, 1966). Pantheon Books. p.113.

- ^ Jung, C. G., and Kerényi, C. (1949). Essays on a Science of Mythology: the Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. Pantheon Books. p.25.

- ^ Jung, C. G., and Kerényi, C. (1949). Essays on a Science of Mythology: the Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. Pantheon Books. p.167.

- ^ For example Kerenyi writes in "Athene: Virgin and Mother in Greek Religion", 1978, translated from German by Murray Stein (German text 1952) Spring Publications, Zurich, : "With Hera the correspondences of the mythological and and cosmic transformation extended to all three phases in which the Greeks saw the moon: she corresponded to the waxing moon as maiden, to the full moon as fulfilled wife, to the waning moon as abandoned withdrawing women" (page 58) He goes on to say that trios of sister goddess in Greek myth refer to the lunar cycle; in the book in question he treats Athene also as a triple moon goddess, noting the statement by Aristotle that Athene was the Moon but not "only" the Moon.

- ^ Neumann, Erich (1955). The Great Mother: an Analysis of the Archetype. Pantheon Books. p.226.

- ^ Neumann, Erich (1955). The Great Mother: an Analysis of the Archetype. Pantheon Books. p.230.

- ^ Von Hendy, Andrew (2002). The Modern Construction of Myth, 2nd edition. Indiana University Press. pp.186-187. ISBN 0-253-33996-0, ISBN 978-0-253-33996-6.

- ^ Pratt, Annis V. (1985). "Spinning Among Fields: Jung, Frye, Levi-Strauss and Feminist Archetypal Theory", in Estella Lauter, Carol Schreier Rupprecht (eds.) (1985). Feminist Archetypal Theory: Interdisciplinary Re-Visions of Jungian Thought. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-7837-9508-4, ISBN 978-0-7837-9508-9.

- ^ Mantecon, Valerie H. (1993). "Where Are the Archetypes? Searching for Symbols of Women's Midlife Passage", pp.83-87, in Nancy D. Davis, Ellen Cole, Esther D. Rothblum (eds.) (1993). Faces of Women and Aging. Routledge. ISBN 1-56024-435-6, ISBN 978-1-56024-435-6.

- ^ Roberts, Jeanne Addison (1994). The Shakespearean Wild: Geography, Genus, and Gender. University of Nebraska Press. passim. ISBN 0-8032-8950-2, ISBN 978-0-8032-8950-5.

- ^ LeGuin, Ursula Kroeber. "The Space Crone", in Ruth Formanek (ed.) (1990). The Meanings of Menopause: Historical, Medical, and Clinical Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 0-88163-080-2, ISBN 978-0-88163-080-0.

- ^ Walker, Barbara G. (1983). The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets. HarperCollins. p.619: "Matres meant the Celtic Triple Goddess, or Three Fates." ISBN 0-06-250925-X, ISBN 978-0-06-250925-3.

- ^ Barbara Walker says the "triple Morrigan" is "the Irish trinity of Fates," composed of the virgin Ana, the mother Badb, and the crone Macha. — Walker, Barbara G. (1983). The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets. HarperCollins. pp.151, 563, 675. ISBN 0-06-250925-X, ISBN 978-0-06-250925-3.

- ^ Atwood, Margaret (2002). Negotiating with the Dead: A Writer on Writing. Cambridge University Press. p.85. ISBN 0-521-66260-5, ISBN 978-0-521-66260-4.

- ^ Reingard M. Nischik (2000). Margaret Atwood: Works and Impact. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-57113-139-6, ISBN 978-1-57113-139-3.

- ^ Bouson, J. Brooks (1993). Brutal Choreographies: Oppositional Strategies and Narrative Design in the Novels of Margaret Atwood. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-845-0, ISBN 978-0-87023-845-1.

- ^ Radford, Andrew D. (2007) The Lost Girls: Demeter-Persephone and the Literary Imagination, 1850-1930, Volume 53 of Studies in Comparative Literature. Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-2235-3, ISBN 978-90-420-2235-5. p.127-128.

- ^ Roberts, Jeanne Addison. "Shades of the Triple Hecate", Proceedings of the PMR Conference 12–13 (1987–88) 47–66, abstracted in John Lewis Walker, Shakespeare and the Classical Tradition, p. 248; revisited by the author in The Shakespearean Wild: Geography, Genus, and Gender (University of Nebraska Press, 1994), passim, but especially pp.142–143, 169ff. ISBN 0-8032-8950-2, ISBN 978-0-8032-8950-5.

- ^ Swift, Carolyn Ruth (1993). (Review of) The Shakespearean Wild in Shakespeare Quarterly, vol.44 no.1 (Spring 1993), pp.96-100.

- ^ Andriano, Joseph (1993). Our Ladies of Darkness: Feminine Daemonology in Male Gothic Fiction. Penn State Press. p.96. ISBN 0-271-00870-9, ISBN 978-0-271-00870-7.

- ^ Wood, Juliette (1999). "Chapter 1, The Concept of the Goddess". In Sandra Billington, Miranda Green (eds.) (1999). The Concept of the Goddess. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 9780415197892. http://books.google.com/books?id=IoW9yhkrFJoC&lpg=PP22&pg=PA22#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ Sanders, Joseph L., and Gaiman, Neil (2006). The Sandman Papers: An Exploration of the Sandman Mythology. Fantagraphics. p.151. ISBN 1-56097-748-5, ISBN 978-1-56097-748-3.

- ^ White, Donna R. (1998). A Century of Welsh Myth in Children's Literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. p.75. ISBN 0-313-30570-6, ISBN 978-0-313-30570-2.

- ^ Holland, Norman Norwood (2006). Meeting Movies. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p.43. ISBN 0-8386-4099-0, ISBN 978-0-8386-4099-9.

- ^ Kaveney, Roz (2005). From Alien to The Matrix. I.B.Tauris. p.151. ISBN 1-85043-806-4, ISBN 978-1-85043-806-9.

- ^ http://radioexile.com/2010/08/21/video-hook-up-the-sword-maiden-mother-crone/

Contemporary Paganism Movements SyncreticAdonism · Christianity · Church of All Worlds · Church of Aphrodite · Feraferia · Neo-Druidism · Neoshamanism · Neo-völkisch movements · Technopaganism · Thelema · Unitarian Universalist · WiccaEthnicApproaches By region German-speaking Europe · Greece · Hungary · Ireland · Latin Europe · Scandinavia · Slavic Europe · UK · USARelated Categories:- Goddesses

- Neopaganism

- Lunar goddesses

- Earth goddesses

- Virgin goddesses

- Fertility goddesses

- Wisdom goddesses

- Triple deities

- Wicca

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.