- Divorce law around the world

-

This article is a general overview of divorce laws around the world. Every nation in the world except the Philippines and the Vatican City allow some form of divorce.

Contents

Muslim societies

In Muslim societies, legislation concerning divorce varies from country to country. Different Muslim scholars can have slightly differing interpretations of divorce in Islam, (e.g. concerning triple talaq).

No-fault divorce is allowed in Muslim societies, although normally only with the consent of the husband. A wife seeking divorce is normally required to give one of several specific justifications (see below).

If the man seeks divorce or was divorced, he has to cover the expenses of his ex-wife feeding his child and expenses of the child until the child is two years old (that is if the child is under two years old). The child is still the child of the couple despite the divorce.

If it is the wife who seeks divorce, she must go to a court. She must provide evidence of ill treatment, inability to sustain her financially, sexual impotence on the part of the husband, her dislike of his looks, etc. The husband may be given time to fix the problem, but if he fails, the appointed judge will grant divorce should the couple still wish to be divorced.[1]

See also: Talaq (conflict) and At-TalaqArgentina

In Argentina, the legalisation of divorce was the result of a struggle between different governments and conservative groups, mostly connected to the Catholic Church. The first attempt to introduce the law was in 1888, but conservative and religious groups kept blocking the bill, which never became a law.

Only in 1954, President Juan Domingo Perón, who was opposed to the Church, had the law passed for the first time in the country. But Perón was forced out of the presidency one year later by a military revolt, and the government that succeeded him, abolished the law.

Finally, in 1987, President Raúl Alfonsín tried to pass the law again, under the strong opposition of a part of the Church, and the tolerance of another part, that nonetheless stated that the new right was not for Catholics, but for the rest of the Argentine society.[dubious ] The most intransigent sectors of the Church asked for the law not to be promulgated, after Congress passed it. They even considered excommunicating the Congress members who had voted favourably. Although this idea was eventually left aside, one bishop did excommunicate Congress members under his jurisdiction.

Brazil

Presumably due to the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, divorce became legal in Brazil only in 1977. Since January 2007,[2] Brazilian couples can request a divorce at a notary's office when there is a consensus and have no underage or special-needs children. The divorcees need only to present their national IDs, marriage certificate and pay a fee to initiate the process, which is completed in two or three weeks.

Previously, a one-year period of separation was required by law before a divorce could take place. However, after the 66th amendment to the country's constitution in 2010, such separation is no longer necessary. Therefore, currently, as long as there is agreement between the divorcees and there are no underage children or incapable persons involved, a divorce may be performed by a notary.

Canada

Canada did not have a federal divorce law until 1968. Before that time, the process for getting a divorce varied from province to province. In Newfoundland and Quebec, it was necessary to get a private Act of Parliament in order to end a marriage. Most other provinces incorporated the English Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 which allowed a husband to get a divorce on the grounds of his wife's adultery and a wife to get one only if she established that her husband committed any of a list of particular sexual behaviours but not simply adultery. Some provinces had legislation allowing either spouse to get a divorce on the basis of adultery.

The federal Divorce Act of 1968 standardized the law of divorce across Canada and introduced the no-fault concept of permanent marriage breakdown as a ground for divorce as well as fault based grounds including adultery, cruelty and desertion.[3]

In Canada, while civil and political rights are in the jurisdiction of the provinces, the Constitution of Canada specifically made marriage and divorce the realm of the federal government. Essentially this means that Canada's divorce law is uniform throughout Canada, even in Quebec, which differs from the other provinces in its use of the civil law as codified in the Civil Code of Quebec as opposed to the common law that is in force in the other provinces and generally interpreted in similar ways throughout the Anglo-Canadian provinces.

The Canada Divorce Act recognizes divorce only on the ground of breakdown of the marriage. Breakdown can only be established if one of three grounds hold: adultery, cruelty, and being separated for one year. Most divorces proceed on the basis of the spouses being separated for one year, even if there has been cruelty or adultery. This is because proving cruelty or adultery is expensive and time consuming.[4] The one-year period of separation starts from the time at least one spouse intends to live separate and apart from the other and acts on it. A couple does not need a court order to be separated, since there is no such thing as a "legal separation" in Canada.[5] A couple can even be considered to be "separated" even if they are living in the same dwelling. Either spouse can apply for a divorce in the province in which either the husband or wife has lived for at least one year.

On September 13, 2004, the Ontario Court of Appeal declared a portion of the Divorce Act also unconstitutional for excluding same-sex marriages, which at the time of the decision were recognized in three provinces and one territory. It ordered same-sex marriages read into that act, permitting the plaintiffs, a lesbian couple, to divorce.[6]

Alberta Divorce Law

In Alberta, The Family Law Act gives clear guidelines to family members, lawyers and judges about the rights and responsibilities of family members. It does not cover divorce, and matters involving family property, and child protection matters. The Family Law Act replaces the Domestic Relations Act, the Maintenance Order Act, the Parentage and Maintenance Act, and parts of the Provincial Court Act and the Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act.[7]

The Family Law Act can be viewed and printed from the Alberta Queen's Printer website.[1]

One goes to the Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta to obtain a declaration of parentage for all purposes if someone has property to be divided or protected court and or for a declaration of irreconcilability.

Separation or Divorce

There is no such thing a legal separation in Canada. Sometimes, when people say they are legally separated, they mean is that they have entered into a legally binding agreement, sometimes called a Separation Agreement, a Divorce Agreement, a Custody, Access and Property Agreement, or a Minutes of Settlement. These types of agreements are usually prepared by lawyers, signed in front of witnesses, and legal advice is given to both parties signing the agreement. However, these types of agreements will, in most cases, be upheld by the courts.[2]

France

The French Civil code (modified on January 1, 2005), permits divorce for 4 different reasons; mutual consent (which comprises over 60% of all divorces); acceptance; separation of 2 years; and due to the 'fault' of one partner (accounting for most of the other 40%).

India

In Hindu religion marriage is sacrament and not a contract, hence divorce was not recognized before the codification of the Hindu Marriage Act in 1955. With the codification of this law, men and women both are equally eligible to seek divorce. Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains are governed by the Hindu Marriage Act 1955, Christians are governed by The Divorce Act 1869, Parsis by the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act 1936, Muslims by the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act 1939 and Inter-religious marriages are governed by The Special Marriage Act 1954.

Conditions are laid down to perform a marriage between a man and woman by these laws. Based on these a marriage is validated, if not it is termed as void marriage or voidable marriage at the option of either of the spouse. Here upon filing a petition by any one spouse before the Court of law a decree of nullity is passed declaring the marriage as null and void.

A valid marriage can be dissolved by a decree of dissolution of marriage or divorce and Hindu Marriage Act, The Divorce Act and Special Marriage Act allow such a decree only on specific grounds as provided in these acts: cruelty, adultery, desertion, apostasy from Hinduism, impotency, venereal disease, leprosy, joining a religious order, not heard of being alive for a period of seven years, or mutual consent where no reason has to be given. Since each case is different, court interpretations of the statutory law gets evolved and have either narrowed or widened their scope.

Family Courts are established to file, hear and dispose of such cases.

Women empowerment and the age old family system of husband being the head and such other several factors has given a sharp rise in marital discords, Indian Courts are flooded with such divorce petitions making the divorce process more traumatising and time consuming.

Ireland

The largely Catholic population of Ireland has tended to be averse to divorce. The position has changed in recent times with a sizeable increase in the number of divorces granted by the Irish Courts. Divorce was prohibited by the 1937 Constitution. While in 1986 the electorate rejected the possibility of allowing divorce in a referendum, the prohibition was ultimately repealed by a 1995 referendum which repealed the prohibition on divorce, despite Church opposition. Laws to give effect to the new position came into effect in 1997, making divorce possible for parties who are separated for four out of the preceding five years. Divorce will not be granted in the Republic of Ireland for any other criteria. It is more difficult to obtain a divorce in Ireland than in other jurisdictions.

A couple must be separated for four of the preceding five years before they can obtain a divorce. It is sometimes possible to be considered separated while living under the same roof.[8]

Divorces obtained outside Ireland are only recognised by the State if either:

- at least one of the spouses was domiciled within the jurisdiction which issued the decree of divorce at the time of issue, or

- the state is required to recognise the divorce pursuant to the relevant European Union regulations — currently Council Regulation (EC) No 2201/2003 concerning jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in matrimonial matters and the matters of parental responsibility.

Italy

Divorce is legal in Italy since a referendum approved on May 13, 1974. Before that, it was generally believed that Italy's obligations under the Lateran Treaty, entered into in 1929, prohibited Italy from authorizing divorce, and, consequently, there was no provision for divorce in Italian law, and the difficulty of ridding oneself of an unwanted spouse in the absence of any legal way to do so was a frequent topic of drama and humor, reaching its apotheosis in the 1961 film Divorce, Italian Style.

Japan

In Japan, there are four types of divorce: Divorce by Mutual Consent, Divorce by Family Court Mediation, Divorce by Family court Judgement, and Divorce by District Court Judgment.[9]

Divorce by mutual consent is a simple process of submitting a declaration to the relevant government office that says both spouses agree to divorce. This form is often called the "Green Form" due to the wide green band across the top. If both parties fail to reach agreement on conditions of a Divorce By Mutual Consent, such as child custody which must be specified on the divorce form, then they must use one of the other three types of divorce. Foreign divorces may also be registered in Japan by bringing the appropriate court documents to the local city hall along with a copy of the Family Registration of the Japanese ex-spouse. If an international divorce includes joint custody of the children, it is important to the foreign parent to register it themselves, because joint custody is not legal in Japan. The parent to register the divorce may thus be granted sole custody of the child according to Japanese law.

Divorce by Mutual Consent in Japan differs from divorce in many other countries, causing it to not be recognized by all countries. It does not require the oversight by courts intended in many countries to ensure an equitable dissolution to both parties. Further, it is not always possible to verify the identity of the non Japanese spouse in the case of an international divorce. This is due to two facts. First, both spouses do not have to be present when submitting the divorce form to the government office. Second, a Japanese citizen must authorize the divorce form using a personal stamp (hanko), and Japan has a legal mechanism for registration of personal stamps. On the other hand, a non-Japanese citizen can authorize the divorce form with a signature. But there is no such legal registry for signatures, making forgery of the signature of a non-Japanese spouse difficult to prevent at best, and impossible to prevent without foresight. The only defense against such forgery is, before the forgery occurs, to submit another form to prevent a divorce form from being legally accepted by the government office at all. This form must be renewed every six months.

Malta

Despite civil marriage being introduced in 1975, no provision was made for divorce except for the recognition of divorces granted by foreign courts. Legislation introducing divorce came into effect in October 2011 following the result of a referendum on the subject earlier in the year. It provides for no-fault divorce, with the marriage being dissolved through a Court judgement following the request of one of the parties, provided the couple has lived apart for at least four years out of the previous five and adequate alimony is being paid or is guaranteed.[10] The same law made a number of important changes regarding alimony, notably through extending it to children born of marriage who are still in full-time education or are disabled and through protecting alimony even after the Court pronounces a divorce.[11]

Philippines

Philippine law, in general, does not provide for divorce inside the Philippines. The only exception is with respect to Muslims, who are allowed to divorce in certain circumstances. For those not of the Muslim faith, the law only allows annulment of marriages. Article 26 of the Family Code of the Philippines does provide that

- Where a marriage between a Filipino citizen and a foreigner is validly celebrated and a divorce is thereafter validly obtained abroad by the alien spouse capacitating him or her to remarry, the Filipino spouse shall have capacity to remarry under Philippine law.[12]

This would seem to apply only if the spouse obtaining the foreign divorce is an alien.[according to whom?] However, the Supreme Court of the Philippines declared in the case of RP vs. Orbecidio

- [..] we are unanimous in our holding that Paragraph 2 of Article 26 of the Family Code (E.O. No. 209, as amended by E.O. No. 227), should be interpreted to allow a Filipino citizen, who has been divorced by a spouse who had acquired foreign citizenship and remarried, also to remarry.[13]

Complications can arise, however. For example, if a legally married Filipino citizen obtains a divorce outside of the Philippines, that divorce would not be recognized inside the Philippines. If that person (now unmarried outside of the Philippines) then remarries outside of the Philippines, he or she could arguably be considered in the Philippines as having committed the crime of bigamy under Philippine Laws.[according to whom?] The above complications will not arise if the legally married Filipino citizen obtains foreign citizenship first, then secures a foreign divorce decree.

Also, Article 15 of the Civil Code of the Philippines provides that

- Laws relating to family rights and duties, or to the status, condition and legal capacity of persons are binding upon citizens of the Philippines, even though living abroad.[14]

This can lead to complications regarding distribution of conjugal property, inheritance rights, etc.[15][16][17] , etc.

In Article 26, paragraph 2 a number of questions can be raised with respect to the operation of this provision, to wit:

- Is there a need for a judicial decree in Philippine courts to declare the Filipino spouse qualified to remarry? The Family Code has no explicit provision to that effect, unlike in cases of void marriages and of a remarriage in case of absence of one of the spouses amounting to presumptive death (Art. 40 and 41, Family Code) where a court decree is required.

- Is Art. 26, par. 2 applicable to foreign divorces obtained before the effectivity of the Family Code in view of Art. 256?

- What if the Filipino spouse does not intend to remarry, what is the status of any children they may have after the divorce decree? Does the Filipino spouse have a right to demand support from his/her former alien spouse? What is his/her status with respect to his/her former foreign spouse? Can he/she claim share of property or income acquired by the former foreign spouse.

The process of the divorce annulment is an expensive one;[according to whom?] it cost about 100,000–200,000 pesos or 2000–4,000 US dollars, which is about a year's wages for a typical Filipino[according to whom?]. The process usually takes 1–2 years.

One of the steps in the process is a psychological assessment for use or reason of annulment. This costs an additional 10,000–15,000 pesos or 200–300 US dollars.

Another step in the process is an interview with a court appointed social worker to eliminate possible "collusion" among the parties involved especially if there are children. Children under the age of 7 are awarded to the mother. There are no standards in child support or support to spouse to maintain her previous standard in society.

The general assumption for this reason for annulment is that the government is influenced by the Catholic religion[according to whom?] and continues to be advised by their leadership rather than a democratic process. However, this conclusion is not necessarily true, and even under the administration of non-Catholic leaders, divorce continues to be a non-issue among majority of Filipinos.

It can be said, instead, that Filipinos (Catholic or not) have an aversion to divorce as they view the family to be sacrosanct and that divorce, in their perception, is absolutely destructive of this. General Filipino perception of divorce is based on the "no-fault" divorce prevalent in some US states which, in their view, is absurd since a divorce (or a separation of partners, at the least) should only be considered if there is a breach in the marriage and not the "whimsical" drive of no-fault divorces.

There is also a lack of general clamor for divorce to be made legal and all attempts to ratify it into law have failed. Intellectuals and some social and civic groups have tried to appeal to the masses to change its perception of divorce but this has failed from time to time.

Filipino law, as stated above, does make some concession to Muslims, though.

Sweden

To divorce in Sweden the couple can file for divorce together or one party can file alone. If they have children under 16 living at home or one party does not wish to get divorced there is a required contemplation period of 6 to 12 months. During this period they stay married and the request must be confirmed after the waiting period for the divorce to go through.[18]

United Kingdom

England and Wales

A divorce in England and Wales is only possible for marriages of more than one year and when the marriage has irretrievably broken down. Whilst it is possible to defend a divorce, the vast majority proceed on an undefended basis. A decree of divorce is initially granted 'nisi', i.e. (unless cause is later shown), before it is made 'absolute'. Relevant laws are:

- Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, which sets out the basis for divorce (part i) and how the courts deal with financial issues, known as ancillary relief (part ii)

- Cruelty has been made irrelevant. See Gollins v Gollins [1964] A.C. 644

- Family Law Act 1996

- Children Act 1989

- Family Proceedings Courts (Matrimonial Proceedings etc.) Rules 1991

- Marriage Act 1949

- Marriage Act 1994

- Gender Recognition Act 2004

Here is a rough outline of the undefended divorce procedure from start to finish:

- Filing of Divorce Petition & if necessary Statement of Arrangements for the Children

- Documents issued by Court and posted to the Respondent

- Respondent returns Acknowledgement of Service to the Court (if he/she does not you will need to consider Bailiff Service, Deemed Service or other options)

- Petitioner completes Affidaviti in Support of Petition and Request for directions

- A Judge will then consider all the divorce papers and if he/she is satisfied issue a Certificate of Entitlement to a Decree and Section 41 Certificate (confirming he/she is content with arrangements for any children)

- Decree Nisi is granted

- Six weeks later the application can be made by the Petitioner for the Decree Absolute.

From beginning to end, if everything goes smoothly and Court permitting, it takes around 6 months.

If there are any outstanding financial issues between the parties, most solicitors would advise resolving these by way of a 'Clean Break' Court order prior to obtaining the Decree Absolute.

There is only one 'ground' for divorce under English law. That is that the marriage has irretrievably broken down.

There are however five 'facts' that may constitute this ground. They are:

- Adultery

- often now considered the 'nice' divorce.

- respondents admitting to adultery will not be penalised financially or otherwise.

- Unreasonable behaviour (most common ground for divorce today [3])

- the petition must contain a series of allegations proving that the respondent has behaved in such a way that the petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with him/her.

- the allegations may be of a serious nature (e.g. abuse or excessive drinking) but may also be mild such as having no common interests or pursuing a separate social life [4]; the courts won't insist on severe allegations as they adopt a realistic attitude: if one party feels so strongly that a behaviour is "unreasonable" as to issue a divorce petition, it is clear that the marriage has irretrievably broken down and it would be futile to try to prevent the divorce. [5]

- Two years separation (if both parties consent)

- both parties must consent

- the parties must have lived separate lives for at least two years prior to the presentation of the petition

- this can occur if the parties live in the same household, but the petitioner would need to make clear in the petition such matters as they ate separately, etc.

- Two years desertion

- Five years separation (if only one party consents)

Scotland

About one third of marriages in Scotland end in divorce, on average after about thirteen years.[19] Actions for divorce in Scotland may be brought in either the Sheriff Court or the Court of Session. In practice, it is only actions in which unusually large sums of money are in dispute, or with an international element, that are raised in the Court of Session. If, as is usual, there are no contentious issues, it is not necessary to employ a lawyer. Divorce (Scotland) Act 1976.

The Divorce (Scotland) Act 1976 provides for separation as a "fact" of irretrievable breakdown after one year with consent or two years without consent after the amendments by the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006. Family law issues are devolved, so are now the responsibility of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Executive.

Financial consequences of divorce are dealt with by the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985. This provides for a division of matrimonial property on divorce. Matrimonial property is generally all the property acquired by the spouses during the marriage but before their separation, as well as housing and furnishings acquired for use as a home before the marriage, but excludes property gifted or inherited. Either party to the marriage can apply to the court for an order under the 1985 Act. The court can make orders for the payment of a capital sum, the transfer of property, the payment of periodical sums, and other incidental orders. In making an order, the court is, under the Act, guided by the following principles:

- The net value of the matrimonial property should be shared fairly, and the starting point is that it should be shared equally; but

- fair account should be taken of economic advantage derived by either party from contributions by the other, and of economic disadvantage suffered by either party in the interests of the other party or of the family; and

- The economic burden of caring for a child of the marriage under 16 years should be shared fairly between the parties (but child support is not normally awarded by the court, as this is in most cases a matter for the Child Support Agency).

The general approach of the Scottish courts is to settle financial issues by the award of a capital sum if at all possible, allowing for a ‘clean break’ settlement, but in some cases periodical allowances may be paid, usually for a limited period. Fault is not normally taken into account.

Decisions as to parental responsibilities, such as residence and contact orders, are dealt with under the Children (Scotland) Act 1995. The guiding principle is the best interests of the child, although the starting assumption is in practice that it is in a child’s best interests to maintain contact with the non-custodial parent.

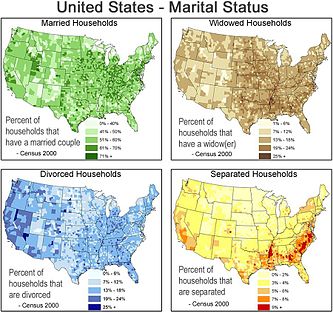

United States

Main article: Divorce in the United StatesDivorce in the United States is a matter of state rather than federal law. In recent years, however, more federal legislation has been enacted affecting the rights and responsibilities of divorcing spouses. The laws of the state(s) of residence at the time of divorce govern; all states recognize divorces granted by any other state. All states impose a minimum time of residence. Typically, a county court’s family division judges petitions for dissolution of marriages.

Before the latter decades of the 20th century, a spouse seeking divorce had to show cause and even then might not be able to obtain a divorce. The legalization of no-fault divorce in the United States began in 1969 in California, and was completed in 2010, with New York being the last of the fifty states to legalize it.[20][21] However, most states still require some waiting period before a divorce, typically a 1– to 2–year separation. Fault grounds, when available, are sometimes still sought. This may be done where it reduces the waiting period otherwise required, or possibly in hopes of affecting decisions related to a divorce, such as child custody, child support, or alimony. Since the mid-1990s, a few states have enacted covenant marriage laws, which allow couples to voluntarily make a divorce more difficult for themselves to obtain than in the typical no-fault divorce action.

Mediation is a growing way of resolving divorce issues. It tends to be less adversarial (particularly important for any children), more private, less expensive, and faster than traditional litigation.[22] Similar in concept, but with more support than mediation, is collaborative divorce, where both sides are represented by attorneys but commit to negotiating a settlement without engaging in litigation. Some believe that mediation may not be appropriate for all relationships, especially those that included physical or emotional abuse, or an imbalance of power and knowledge about the parties' finances.

States vary in their rules for division of assets. Some states are "community property" states, others are "equitable distribution" states, and others have elements of both. Most "community property" states start with the presumption that community assets will be divided equally, whereas "equitable distribution" states presume fairness may dictate more or less than half of the assets will be awarded to one spouse or the other. Commonly, assets acquired before marriage are considered individual, and assets acquired after, marital. Attempt is made to assure the welfare of any minor children generally through their dependency. Alimony, also known as 'maintenance' or 'spousal support', is still being granted in many cases, especially in longer term marriages.

A decree of divorce will generally not be granted until all questions regarding child care and custody, division of property and assets, and ongoing financial support are resolved.

Due to the complex divorce procedures required in many places, some people seek divorces from other jurisdictions that have easier and quicker processes. Most of these places are commonly referred to negatively as "divorce mills."

Global issues

Where people from different countries get married, and one or both then choose to reside in another country, the procedures for divorce can become significantly more complicated. Although most countries make divorce possible, the form of settlement or agreement following divorce may be very different depending on where the divorce takes place. In some countries there may be a bias towards the man regarding property settlements, and in others there may be a bias towards the woman concerning property and custody of any children. One or both parties may seek to divorce in a country that has jurisdiction over them. Normally there will be a residence requirement in the country in which the divorce takes place. See also Divorces obtained by US couples in a different country or jurisdiction above for more information, as applicable globally. In the case of disputed custody, almost all lawyers would strongly advise following the jurisdiction applicable to the dispute, i.e. the country or state of the spouse's residence. Even if not disputed, the spouse could later dispute it and potentially invalidate another jurisdiction's ruling.

Some of the more important aspects of divorce law involve the provisions for any children involved in the marriage, and problems may arise due to abduction of children by one parent, or restriction of contact rights to children. For the Conflict of Laws issues, see divorce (conflict).

References

- ^ Amani Aboul Fadl Farag. "Laws of divorce". islamonline.net. Archived from the original on 2006-07-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20060722100355/http://www.islamonline.net/askaboutislam/display.asp?hquestionID=3202. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ^ Irene Lôbo. "Nova lei de divórcio promete facilitar a vida das pessoas" (in Portuguese). islamonline.net. Archived from the original on 2007-02-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20070228142558/http://www.agenciabrasil.gov.br/noticias/2007/01/26/materia.2007-01-26.3557347427/view. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ^ Douglas, Kirsten (Revised 27 March 2001). "Divorce law in canada". Law and Government Division, Department of Justice, Government of Canada. http://dsp-psd.communication.gc.ca/Pilot/LoPBdP/CIR/963-e.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ^ "Family law, child custody, child & spousal support, property division & more". ottawadivorce.com. http://www.ottawadivorce.com. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ^ "Family law, child custody, child & spousal support, property division & more". A1-ontario-divorce.com. http://www.A1-ontario-divorce.com. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ^ "Ontario court approves first same-sex divorce". theglobeandmail.com. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20040913.wdivor0913/BNStory/National/. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ^ Alberta Courts website: http://www.albertacourts.ab.ca/go/CourtServices/FamilyJusticeServices/FamilyLawAct/tabid/127/Default.aspx

- ^ McA v McA [2000] 2 ILRM 48.

- ^ Japan Children's Rights Network. "Types of Divorce In Japan". http://www.crnjapan.com/divorce/en/types_of_divorce_in_japan.html. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ^ Act XIV of 2011 amending the Civil Code

- ^ http://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20110819/opinion/Divorce-and-maintenance.380840

- ^ "Family Code of the Philippines". http://www.chanrobles.com/executiveorderno209.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "RP vs. Orbecidio, G.R. No. 154380, October 5, 2005". http://www.supremecourt.gov.ph/jurisprudence/2005/oct2005/154380.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "Civil Code of the Philippines". http://www.chanrobles.com/civilcodeofthephilippines1.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "Van Dorn vs. Romillo, G.R. No. L-68470 October 8, 1985". http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri1985/oct1985/gr_l68470_1985.html. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "Licaros vs. Licaros, G.R. No. 150656. April 29, 2003". http://www.supremecourt.gov.ph/jurisprudence/2003/apr2003/150656.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "Llorente vs. Court of Appeals and Llorente, G.R. No. 124371. November 23, 2000". http://www.supremecourt.gov.ph/jurisprudence/2003/feb2003/..%5C..%5C2000%5Cnov2000%5C124371.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "Divorce". Sveriges Domstolar - Domstolsverket, Swedish National Courts Administration. 2007-03-07. http://www.domstol.se/templates/DV_InfoPage____2413.aspx. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Morrison, Anita; Debbie Headrick, Legal Studies Research Team, Scottish Executive Fran Wasoff, Sarah Morton (March 2004). "Family formation and dissolution: Trends and attitudes among the Scottish population". Scottish Executive Research 43. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/cru/resfinds/lsf43-00.asp. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ^ AP (2010-08-16). "New York becomes last state to recognize 'no fault' divorces". NYPOST.com. http://www.nypost.com/p/news/local/ny_last_state_to_recognize_no_fault_mzWXGD1R94ZxX6c85MjOWI. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ "No-Fault Divorce - The Pros and Cons Of No-Fault Divorce". Divorcesupport.about.com. 2010-07-30. http://divorcesupport.about.com/od/maritalproblems/i/nofault_fault_2.htm. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ Hoffman, David A.; Karen Tosh (1999). "Coaching From The Sidelines: Effective Advocacy In Divorce Mediation" (PDF). Massachusetts Family Law Journal 85. Archived from the original on 2006-08-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20060822072744/http://bostonlawcollaborative.com/documents/2005-07-coaching-from-the-sidelines.pdf. Retrieved 2006-09-10.

Also:

- Amato, Paul R. and Alan Booth. A Generation at Risk: Growing Up in an Era of Family Upheaval. (Harvard University Press, 1997)ISBN 0-674-29283-9 and ISBN 0-674-00398-5. Reviews and information at [6]

- Gallagher, Maggie. The Abolition of Marriage (Regnery Publishing, 1996) ISBN 0-89526-464-1.

- Lester, David. "Time-Series Versus Regional Correlates of Rates of Personal Violence." Death Studies 1993: 529-534.

- McLanahan, Sara and Gary Sandefur. Growing Up with a Single Parent; What Hurts, What Helps. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994: 82)

- Morowitz, Harold J. Hiding in the Hammond Report (Hospital Practice. August 1975; 39)

- Stansbury, Carlton D. and Kate A. Neugent Is the Haugan decision functionally obsolete? (Wisconsin Law Journal. February 18, 2008)

- Office for National Statistics (UK). Mortality Statistics: Childhood, Infant and Perinatal Review of the Registrar General on Deaths in England and Wales, 2000, Series DH3 33, 2002.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Marriage and Divorce. General US survey information. [7]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Survey of Divorce [8] (link obsolete).

Categories:- Divorce law

- Family law by country

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.