- Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937

-

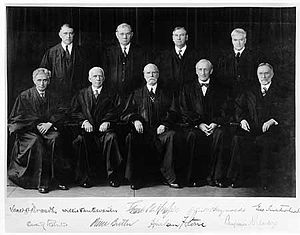

The Hughes Court, 1932–1937. Front row: Justices Brandeis and Van Devanter, Chief Justice Hughes, and Justices McReynolds and Sutherland. Back row: Justices Roberts, Butler, Stone, and Cardozo.

The Hughes Court, 1932–1937. Front row: Justices Brandeis and Van Devanter, Chief Justice Hughes, and Justices McReynolds and Sutherland. Back row: Justices Roberts, Butler, Stone, and Cardozo.

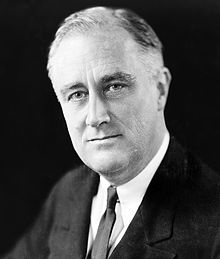

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His dissatisfaction over Supreme Court decisions holding New Deal programs unconstitutional prompted him to seek out methods to change the way the court functioned.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His dissatisfaction over Supreme Court decisions holding New Deal programs unconstitutional prompted him to seek out methods to change the way the court functioned.

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937,[1] frequently called the court-packing plan,[2] was a legislative initiative proposed by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt to add more justices to the U.S. Supreme Court. Roosevelt's purpose was to obtain favorable rulings regarding New Deal legislation that had been previously ruled unconstitutional.[3] The central and most controversial provision of the bill would have granted the President power to appoint an additional Justice to the U.S. Supreme Court, up to a maximum of six, for every sitting member over the age of 70 years and 6 months.

During Roosevelt's first term,[4] the Supreme Court had struck down several New Deal measures intended to bolster economic recovery during the Great Depression, leading to charges from New Deal supporters that a narrow majority of the court was obstructionist and political. Since the U.S. Constitution does not mandate any specific size of the Supreme Court, Roosevelt sought to counter this entrenched opposition to his political agenda by expanding the number of justices in order to create a pro-New Deal majority on the bench.[3] Opponents viewed the legislation as an attempt to stack the court, leading to the name "Court-packing Plan".[2]

The legislation was unveiled on February 5, 1937 and was the subject, on March 9, 1937, of one of Roosevelt's Fireside chats.[5][6] Shortly after the radio address, on March 29, the Supreme Court published its opinion upholding a Washington state minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish[7] by a 5–4 ruling, after Associate Justice Owen Roberts had joined with the wing of the bench more sympathetic to the New Deal. Since Roberts had previously ruled against most New Deal legislation, his perceived about-face was widely interpreted by contemporaries as an effort to maintain the Court's judicial independence by alleviating the political pressure to create a court more friendly to the New Deal. His move came to be known as "the switch in time that saved nine." However, since Roberts's decision and vote in the Parrish case predated the introduction of the 1937 bill,[8] this interpretation has been called into question as an anachronistic "winner's history."[9]

Roosevelt's initiative ultimately failed due to adverse public opinion, the retirement of one Supreme Court Justice, and the unexpected and sudden death of the legislation's U.S. Senate champion: Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson. It exposed the limits of Roosevelt's abilities to push forward legislation through direct public appeal and, in contrast to the tenor of his public presentations of his first-term, was seen as political maneuvering.[10][11] Although circumstances ultimately allowed Roosevelt to prevail in establishing a majority on the court friendly to his New Deal agenda, some scholars have concluded that the President's victory was a pyrrhic one.[11]

Contents

Background

New Deal

Main article: New DealFollowing the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the onset of the Great Depression and the inability of the Hoover administration to respond to the financial crisis, Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election on a promise to give America a "New Deal" to promote national economic recovery. The 1932 election also saw a new Democratic majority sweep into both houses of Congress, giving Roosevelt legislative support for his reform platform. Both Roosevelt and the 73rd Congress called for greater governmental involvement in the economy as a way to end the depression.[12] During the president's first term, a series of successful constitutional challenges to various New Deal programs were launched in federal courts.

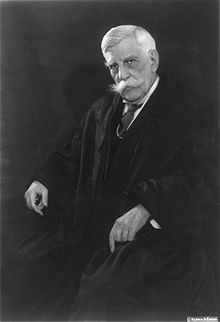

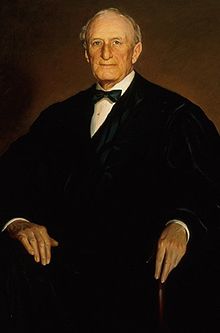

Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. The loss of half his pension pay due to New Deal legislation after Holmes's 1932 retirement is believed to have dissuaded Justices Van Devanter and Sutherland from departing the bench.

Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. The loss of half his pension pay due to New Deal legislation after Holmes's 1932 retirement is believed to have dissuaded Justices Van Devanter and Sutherland from departing the bench.

A minor aspect of Roosevelt's New Deal agenda may have itself directly precipitated the showdown between the Roosevelt administration and the Supreme Court. Shortly after Roosevelt's inauguration, Congress passed the Economy Act, a provision of which cut many government salaries, including the pensions of retired Supreme Court justices. Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who had retired in 1932, saw his pension halved from $20,000 to $10,000 per year; Holmes originally had his pension halved in 1932,[13] but Congress had temporarily restored it to $20,000.00 per year in February of 1933.[13] The serious cut to pensions appears to have dissuaded at least two older Justices, Willis Van Devanter and George Sutherland, from retirement.[14] Both would later find many aspects of the New Deal unconstitutional.

Roosevelt's Justice Department

The flurry of new law in the wake of Roosevelt's first hundred days swamped the Justice Department with more responsibilities than it could manage.[15] Many Justice Department lawyers were ideologically opposed to the New Deal and failed to influence either the drafting or review of much of the White House's New Deal legislation.[16] The ensuing struggle over ideological identity increased the ineffectiveness of the Justice Department. As Interior Secretary Harold Ickes complained, Attorney General Homer Cummings had "simply loaded it [the Justice Department] with political appointees" at a time when it would be responsible for litigating the flood of cases arising from New Deal legal challenges.[17]

Compounding matters, Roosevelt's congenial Solicitor General, James Crawford Biggs (a patronage appointment chosen by Cummings), proved to be an ineffective advocate for the legislative initiatives of the New Deal.[18] While Biggs resigned in early 1935, his successor Stanley Forman Reed proved to be little better.[15]

This disarray at the Justice Department meant that the government's lawyers often failed to foster viable test cases and arguments for their defense, subsequently handicapping them before the courts.[16] As Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes would later note, it was because much of the New Deal legislation was so poorly drafted and defended that the court did not uphold it.[16]

Jurisprudential debate

See also: History of the Supreme Court of the United States and Lochner eraModern popular histories cast the membership of the Hughes Court as aligned with—and in light of—modern political ideologies: Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland and Willis Van Devanter (collectively called "The Four Horsemen") are deemed "conservative", meanwhile Louis Brandeis, Benjamin Cardozo and Harlan Fiske Stone (dubbed "The Three Musketeers") are portrayed as "liberals" politically opposed to the Horsemen; finally, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Owen Roberts, were regarded as swing voters.[19] It is true that in many of their rulings the Supreme Court of the 1930s was deeply divided: four justices on each side, with Justice Roberts as the typical swing vote. However, the ideological divide between a so-called progressive and reactionary wing is misleading insofar as these terms suggest political and not jurisprudential differences. More recent scholarship has focused on the larger debate in U.S. jurisprudence regarding the role of the judiciary, the meaning of the Constitution, and the respective rights and prerogatives of the different branches of government in shaping the judicial outlook of the Court.[20]

The clash over the constitutionality of the New Deal initiatives was thus tied to divergent legal philosophies gradually coming into competition with each other: legal formalism and legal realism.[21] During the period ca. 1900 – ca. 1920, the formalist and realist camps clashed over the nature and legitimacy of judicial authority in common law, given the lack of a central, governing authority in those legal fields other than the precedent established by case law—i.e., the aggregate of earlier judicial decisions.[21]

This debate spilled over into the realm of constitutional law.[21] Realist legal scholars and judges argued that the constitution should be interpreted flexibly and judges should not use the Constitution to impede legislative experimentation. One of the most famous proponents of this concept, known as the Living Constitution, was U.S. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who said in Missouri v. Holland the "case before us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago".[22][23] The conflict between formalists and realists implicated a changing but still-persistent view of constitutional jurisprudence which viewed the U.S. Constitution as a static, universal, and general document not designed to change over time. Under this judicial philosophy, case resolution required a simple restatement of the applicable principles which were then extended to a case's facts in order to resolve the controversy.[24] This earlier judicial attitude came into direct conflict with the legislative reach of much of Roosevelt's New Deal legislation. Examples of these judicial principles include:

- the early-American fear of centralized authority which necessitated an unequivocal distinction between national powers and reserved state powers;

- the clear delineation between public and private spheres of commercial activity susceptible to legislative regulation; and

- the corresponding separation of public and private contractual interactions based upon "free labor" ideology and Lockean property rights.[25]

At the same time, developing modernist ideas regarding politics and the role of government placed the role of the judiciary into flux. The courts were generally moving away from what has been called "guardian review" — in which judges defended the line between appropriate legislative advances and majoritarian encroachments into the private sphere of life — toward a position of "bifurcated review". This approach favored sorting laws into categories that demanded deference towards other branches of government in the economic sphere, but aggressively heightened judicial scrutiny with respect to fundamental civil and political liberties.[26] The slow transformation away from the "guardian review" role of the judiciary brought about the ideological—and, to a degree, generational—rift in the 1930s judiciary. With the Judiciary Bill, Roosevelt sought to accelerate this judicial evolution by diminishing the dominance of an older generation of judges who remained attached to an earlier mode of American jurisprudence.[25][27]

The New Deal goes to court

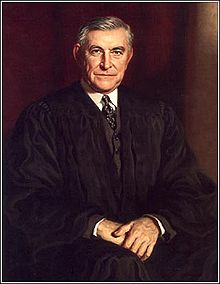

Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts. The balance of the Supreme Court in 1935 caused the Roosevelt administration much concern over how Roberts would adjudicate New Deal challenges.

Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts. The balance of the Supreme Court in 1935 caused the Roosevelt administration much concern over how Roberts would adjudicate New Deal challenges.

Roosevelt was wary of the Supreme Court early in his first term, and his administration was slow to bring constitutional challenges of New Deal legislation before the court.[28] However, early wins for New Deal supporters came in Home Building & Loan Association v. Blaisdell[29] and Nebbia v. New York[30] at the start of 1934. At issue in each case were state laws relating to economic regulation. Blaisdell concerned the temporary suspension of creditor's remedies by Minnesota in order to combat mortgage foreclosures, finding that temporal relief did not, in fact, impair the obligation of a contract. Nebbia held that New York could implement price controls on milk, in accordance with the state's police power. While not tests of New Deal legislation themselves, the cases gave cause for relief of administration concerns about Associate Justice Owen Roberts, who voted with the majority in both cases.[31] Roberts's opinion for the court in Nebbia was also encouraging for the administration:[28]

[T]his court from the early days affirmed that the power to promote the general welfare is inherent in government.[32]Nebbia also holds a particular significance: it was the one case in which the Court abandoned its jurisprudential distinction between the "public" and "private" spheres of economic activity, an essential distinction in the court's analysis of state police power.[27] The effect of this decision radiated outward, affecting other doctrinal methods of analysis in wage regulation, labor, and the power of the U.S. Congress to regulate commerce.[25][27]

Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan

The first major test of New Deal legislation came in Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan,[33] announced January 7, 1935. Contested in this case was the National Industrial Recovery Act, Section 9(c), in which Congress had delegated to the President authority "to prohibit the transportation in interstate and foreign commerce of petroleum ... produced or withdrawn from storage in excess of the amount permitted ... by any State law".[34] The NIRA passed in June 1933, and Roosevelt moved quickly to file executive orders to regulate the oil industry. Two small, independent oil producers, Panama Refining Co. and Amazon Petroleum Co. filed suit seeking an injunction to halt enforcement, arguing that the law exceeded Congress's interstate commerce power and improperly delegated authority to the President.

The Supreme Court, through an 8-1 margin,[35] agreed with the oil companies, finding that Congress had inappropriately delegated its regulatory power without both a clear statement of policy and the establishment of a specific set of standards by which the President was empowered to act. Although somewhat of a loss for the Roosevelt administration and New Deal supporters, it was mitigated by the narrowness of the court's opinion, which did not deny Congress's authority to regulate interstate oil commerce.[36] Chief Justice Hughes, who wrote the majority opinion, indicated that the law was just poorly worded and that Congress could resolve the unconstitutional provisions of the Act by simply adding procedural safeguards,[37] hence the Connally Hot Oil Act of 1935 was passed into law.[38]

Gold Clause Cases

Main articles: Emergency Banking Act and Gold Clause CasesEconomic regulation again appeared before the Supreme Court in the Gold Clause Cases.[39] In his first week after taking office, Roosevelt closed the nation's banks, acting from fears that gold hoarding and international speculation posed a danger to the national monetary system. He based his actions on the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917.[40] Congress quickly ratified Roosevelt's action with the Emergency Banking Act. A month later, the President issued Executive Order 6102, confiscating all gold coins, bullion, and certificates, requiring they be surrendered to the government by May 1, 1933 in exchange for currency. Congress also passed a joint resolution cancelling all gold clauses in public and private contracts, stating such clauses interfered with its power to regulate U.S. currency.

While the Roosevelt administration waited for the court to return its judgment, contingency plans were made for an unfavorable ruling.[41] Ideas circulated within the White House to withdraw the right to sue the government to enforce gold clauses.[41] Attorney General Cummings suggested the court should be immediately packed to ensure a favorable ruling.[41] Roosevelt himself ordered the Treasury to manipulate the market to give the impression of turmoil, although Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau refused.[41] Roosevelt also drew up executive orders to close all stock exchanges and prepared a radio address to the public.[41]

On February 18, 1935, the Justices' decisions in all three cases were announced; all supported the government's position by a narrow 5–4 majority.[41] Chief Justice Hughes wrote the opinion for each case, finding the government had plenary power to regulate money. As such, the abrogation of both private and public contractual gold clauses was within congressional reach when such clauses represented a threat to Congress's control of the monetary system.[41] Speaking for the Court in the Perry case, Hughes's opinion was remarkable: in a judicial tongue-lashing not seen since Marbury v. Madison,[42] Hughes chided Congress for an act which, while legal, was regarded as clearly immoral.[36] However, Hughes ultimately found the plaintiff had no cause of action, and thus no standing to sue the government.[43]

Railroad Retirement Board v. Alton Railroad Co.

While not itself a part of the New Deal, the Roosevelt administration kept a close eye on the challenge to the 1934 Railroad Retirement Act, Railroad Retirement Board v. Alton Railroad Co..[44] Its similarity with the Social Security Act meant the test of the railroad pension regime would serve as an indicator of whether Roosevelt's ambitious retirement program would be found constitutional.[45] The railroad pension was designed to encourage older rail workers to retire, thereby creating jobs for younger railroaders desperately in need of work, although ostensibly Congress passed the act on the grounds that it would increase safety on the country's railways.[45]

Numerous challenges to the law were filed in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, and injunctions were issued on the grounds that the law was an unconstitutional regulation of an activity not connected to interstate commerce.[45] The Supreme Court took the case without waiting for an appeal to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals.[46]

On May 6, 1935, Justice Roberts's 5–4 opinion for the Court rejected the government's position, dismissing the purported effect on railway safety as "without support in reason or common sense".[45] Further, Roberts took issue with a provision of the act which awarded pension computation credit to former rail workers, regardless of when they had last worked in the industry.[45] Roberts characterized the provision as "a naked appropriation of private property" — taking the belongings "of one and bestowing it upon another" — and a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.[45]

Black Monday

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes. Hughes believed the primary objection of the Supreme Court to the New Deal was its poorly drafted legislation.

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes. Hughes believed the primary objection of the Supreme Court to the New Deal was its poorly drafted legislation.

Just three weeks after its defeat in the railroad pension case, the Roosevelt administration suffered its most severe setback, on May 27, 1935: "Black Monday".[47] Chief Justice Hughes arranged for the decisions announced from the bench that day to be read in order of increasing importance.[47] The Supreme Court ruled unanimously against Roosevelt in three cases[35]

Humphrey's Executor v. United States

The first of the three read out was Humphrey's Executor v. United States.[48] After taking office, President Roosevelt came to believe that William Humphrey, a Republican appointed to a six-year term on the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 1931, was at odds with the administration's New Deal initiatives. Writing to request Humphrey's resignation from the FTC in August 1933, Roosevelt openly admitted his reason for seeking his removal: "I did not feel that your mind and my mind go along together."[49] This proved to be a blunder on Roosevelt's part.[49] When Humphrey could not be persuaded to resign, Roosevelt dismissed him from office on October 7."[50]

Humphrey promptly filed suit to return to his appointed office and to collect backpay. The basis for his suit was the 1914 Federal Trade Commission Act, which specified that the President was only authorized to remove a FTC commissioner "for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office".[51] Humphrey died on February 14, 1934 and his suit was carried on by his wife — as executor of his estate — for backpay up to the date of his death (with interest).

Associate Justice George Sutherland read the court's opinion, holding that Roosevelt had indeed acted outside of his authority when he fired Humphrey from the FTC, stating that Congress had intended regulatory commissions such as the FTC to be independent of executive influence.[52]

Louisville Joint Stock Land Bank v. Radford

Next announced was Louisville Joint Stock Land Bank v. Radford.[53] The 1934 Frazier-Lemke Farm Bankruptcy Act was designed to give aid to debt-ridden farmers, allowing them to reacquire farms they had lost from foreclosure, or to petition the Bankruptcy Court within their district to suspend foreclosure proceedings.[54] The legislation's ultimate goal was to help those farmers scale down their mortgages.[54]

The opinion of the court, read by Justice Louis Brandeis, struck down the act on Fifth Amendment Takings Clause grounds. The court found the act stripped the creditor of property which was held before the passage of the act, without any form of compensation, and bestowed the property upon the debtor.[52] Further, the act allowed the debtor to remain on the mortgaged property for up to five years after declaring bankruptcy, giving the creditor no opportunity to foreclose immediately.[52] While the states could not impair contract obligations, the federal government could—but it could not take property in such a manner without compensating the creditor.[52]

Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States

The final blow for the President on Black Monday fell with the reading of Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States,[55] which revisited the National Industrial Recovery Act, invalidating the NIRA in its entirety.

Under Section 3 of the NIRA, the President had promulgated the Live Poultry Code to regulate the New York poultry market. The Schechter brothers had been charged with criminal violations of the code and were convicted, whereupon they appealed on grounds that the NIRA was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive, the NIRA sought to regulate business which was not engaged in interstate commerce, and that certain sections violated the Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause.

Chief Justice Hughes delivered the opinion of the unanimous court, holding that Congress had delegated too much lawmaking authority to the President without any clear guidelines or standards.[56] Section 3 granted either trade associations or the President authority to draft "codes of fair competition", which amounted to a capitulation of congressional legislative authority.[56] The arrangement presented the danger that private entities, and not government officials, could engage in creating codes of law enforceable upon the public.[56] Justice Benjamin Cardozo, who had been the lone dissent in the similar Panama case, agreed with the majority. In his concurring opinion, Cardozo described Section 3 as "delegation run riot".[56]

Hughes also renewed an old method of jurispudence concerning the "current of commerce" theory of the Commerce Clause as expounded by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in Swift v. United States.[57][58] Hughes determined the poultry at issue in the case, though purchased for slaughter interstate, were not intended for any further interstate transactions after Schecter slaughtered them. Thus, the poultry were outside of Congress's authoritative reach unless Schecter's business had a direct and logical connection to interestate commerce, per the Shreveport Rate Case.[59] Hughes used a direct/indirect effect analysis to determine the Schechters' business was not within the reach of congressional regulation.[58]

Roosevelt reacts

Upon learning of the unanimity of the three court decisions, Roosevelt became distressed and irritable, regarding the opinions as personal attacks.[60] The Supreme Court's decision in Humphrey's Ex. particularly stunned the administration.[61] Only nine years earlier, in Myers v. United States,[62] the Taft Court had held the President's power to remove executive officials was plenary. Roosevelt and his entourage viewed Sutherland's particularly vicious criticism as an attempt to publicly shame the President and paint him as having purposefully violated the Constitution.[61]

After the decisions came down, Roosevelt remarked at a May 31 press conference that the Schechter decision had "relegated [the nation] to a horse and buggy definition of interstate commerce".[63] The comment lit a fire under the media and indignated the public.[64] Scorned for the perceived attack on the court, Roosevelt assumed a diplomatic silence toward the court and waited for a better opportunity to press his cause with the public.[64]

Further setbacks

Attorney General Homer Stillé Cummings. His failure to prevent poorly-drafted New Deal legislation from reaching Congress is considered his greatest shortcoming as Attorney General.[16]

Attorney General Homer Stillé Cummings. His failure to prevent poorly-drafted New Deal legislation from reaching Congress is considered his greatest shortcoming as Attorney General.[16]

With several cases laying forth the criteria necessary to respect the due process and property rights of individuals, and statements of what constituted an appropriate delegation of legislative powers to the President, Congress quickly revised the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA).[65] However, New Deal supporters still wondered how the AAA would fare against Chief Justice Hughes's restrictive view of the Commerce Clause from the Schechter decision.

United States v. Butler

The AAA received its trial in the case of United States v. Butler,[66] announced January 6, 1936. The AAA had created an agricultural regulatory program with a supporting processing tax; the revenue raised was then specifically used to pay farmers to reduce their acreage and production, which would in turn reduce surplus harvest yields and increase prices. Officials of the Hoosac Mills Corp. argued that the AAA was as unconstitutional as the National Industrial Recovery Act, attempting to regulate activity not in interstate commerce. Specifically attacked was the use of Congress's Taxing and Spending power undergirding the program.[65] On January 6, 1936, the Supreme Court ruled the AAA unconstitutional by a 6-3 margin.[67]

Associate Justice Roberts again delivered the opinion of a divided court, agreeing with those challenging the tax. Regarding agriculture as an essentially local activity, the court invalidated the AAA as a violation of the powers reserved to the states under the Tenth Amendment.[65] The court also used the occasion to settle a dispute over the General Welfare Clause stemming back to the administration of George Washington, holding Congress possessed a power to tax and spend for the general welfare.[65]

Carter v. Carter Coal Co.

Following the undoing of the National Recovery Administration by the Schechter decision, Congress attempted to salvage the coal industry code promulgated under the National Industrial Recovery Act in the Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935.[68] The act, closely following the criteria of the Schechter ruling, declared a public interest in coal production and found it so integrated into interstate commerce as to warrant federal regulation.[68] The code subjected the coal industry to labor, price, and practice regulations, levying a 15 percent tax on all producers with a provision to refund a significant portion of the tax for those adhering to the legislation's dictates.[69] James Carter, shareholder and president of the Carter Coal Co., filed suit against the board of directors when they voted to pay the tax.[70]

On May 18, 1936, the Supreme Court ruled the act unconstitutional by a 5-4 margin.[71] Associate Justice Sutherland read the Carter v. Carter Coal Company[72] opinion, striking down the coal act in its entirety, citing the Schechter decision. Most surprising in the opinion was reliance on 19th-century cases legal scholars had thought long repudiated: Kidd v. Pearson[73] and United States v. E. C. Knight Co.[74]

Ashton v. Cameron County Water Improvement Dist. No. 1

On May 25, 1936, the Supreme Court ruled the 1934 Municipal Bankruptcy Act (also known as the Sumners-Wilcox Bill) was unconstitutional in a 5-4 decision.[75] The law amended the Federal Bankruptcy Act and permitted any municipality or other political subdivision of any state to obtain a voluntary readjustment of its debts through proceedings in Federal Court.[75] Texas' Cameron County Water Improvement Dist. No. 1, which claimed to be insolvent and unable to meets its debts in the long run,[75] petitioned the local Federal District Court for readjustments granted under the Municipal Bankruptcy Act.[75] The case eventually reached the Supreme Court, which found that the law violated Tenth Amendment rights of state sovereignty.[75]

Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo

The final provocation for New Deal supporters came in the overturning of a New York minimum wage statute on June 1, 1936. Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo[76] was an important attempt among New Deal supporters to overturn a prior Supreme Court decision prohibiting wage price controls, Adkins v. Children's Hospital.[77] Felix Frankfurter, who had led the earlier unsuccessful arguments before the Supreme Court, worked carefully to craft the law for the New York legislature so it would stand up to challenges based upon the Adkins opinion.[78]

The case resulted from the indictment of a Brooklyn laundry owner John Tipaldo, who not only had failed to pay his female employees the required minimum salary ($12.40 per week), but had further hidden his transgression by falsifying his books.[79] Tipaldo contested the law under which he was charged as unconstitutional and filed for habeas corpus relief. The New York Court of Appeals found itself in agreement with Tipaldo, being unable to find any substantial difference between the New York law and the Washington, D.C. law overturned in Adkins.[79]

How the court split its vote in this case is supportive of challenges to the "switch in time" narrative. Justices Brandeis, Stone, and Cardozo each thought Adkins was incorrectly decided and wanted to overturn it. Chief Justice Hughes believed the New York law differed from the law in Adkins and wanted to uphold the New York statute. Justices Van Devanter, McReynolds, Sutherland, and Butler found no distinctions and voted to uphold the habeas corpus petition.[80] The outcome of the Tipaldo case thus hung in the balance of Justices Roberts's vote.[79] Roberts could find no distinction in the two minimum wage laws, but appears to have been inclined to support an overturning of Adkins anyway.[81] However, there was a problem: the appellant had not taken issue with the Adkins precedent and failed to challenge it.[82][83] Having no "case or controversy" legs upon which to stand, Roberts deferred to the Adkins precedent.[83]

Roosevelt broke his year-long silence on Supreme Court issues to comment on the Tipaldo opinion:

It seems to be very clear, as a result of this decision and former decisions, using this question of minimum wage as an example, that the "no man's land" where no government—state or federal—can function is being more clearly defined. A state cannot do it and the federal government cannot do it.[84]Antecedents to the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill

Associate Justice James Clark McReynolds. A legal opinion authored by McReynolds in 1914, while U.S. Attorney General, is the most probable source for Roosevelt's court reform plan.

Associate Justice James Clark McReynolds. A legal opinion authored by McReynolds in 1914, while U.S. Attorney General, is the most probable source for Roosevelt's court reform plan.

The coming conflict with the court was foreshadowed by a campaign statement Roosevelt had made in 1932:

After March 4, 1929, the Republican party was in complete control of all branches of the government—the legislature, with the Senate and Congress; and the executive departments; and I may add, for full measure, to make it complete, the United States Supreme Court as well.[85]An April 1933 letter to the president offered the idea of packing the Court: "If the Supreme Court's membership could be increased to twelve, without too much trouble, perhaps the Constitution would be found to be quite elastic."[85] The next month, soon-to-be Republican National Chairman Henry Plather Fletcher expressed his concern: "[A]n administration as fully in control as this one can pack it [the Supreme Court] as easily as an English government can pack the House of Lords."[85]

Searching out solutions

As early as the autumn 1933, Roosevelt had begun anticipation of reforming a federal judiciary composed of a stark majority of Republican appointees at all levels.[86] Roosevelt tasked Attorney General Homer Cummings with a year-long "legislative project of great importance".[87] Justice Department lawyers then commenced research on the "secret project," with Cummings devoting what time he could.[87] The focus of the research was directed at restricting or removing the Supreme Court's power of judicial review.[87] However, an autumn 1935 Gallup Poll had returned a majority disapproval of attempts to limit the Supreme Court's power to declare acts unconstitutional.[88] For the time being, Roosevelt stepped back to watch and wait.[89]

Other alternatives were also sought: Roosevelt inquired about the rate at which the Supreme Court denied certiorari, hoping to attack the Court for the small number of cases it heard annually. He also asked about the case of Ex parte McCardle, which limited the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, wondering if Congress could strip the Court's power to adjudicate constitutional questions.[87] The span of possible options even included constitutional amendments; however, Roosevelt soured to this idea, citing the requirement of three-fourths of state legislatures needed to ratify, and that an opposition wealthy enough could too easily defeat an amendment.[90] Further, Roosevelt deemed the amendment process in itself too slow when time was a scarce commodity.[91]

Unexpected answer

Attorney General Cummings received novel advice from Princeton University professor Edward S. Corwin in a December 16, 1936 letter. Corwin had relayed an idea from Harvard University professor Arthur Holcombe, suggesting that Cummings tie the size of the Supreme Court's bench to the age of the justices since the popular view of the Court was critical of their age.[92] However, another related idea fortuitously presented itself to Cummings as he and his assistant Carl McFarland were finishing their collaborative history of the Justice Department, Federal justice: chapters in the history of justice and the Federal executive. An opinion written by Associate Justice McReynolds—one of Cumming's predecessors as Attorney General, under Woodrow Wilson—had made a proposal in 1914 which was highly relevant to Roosevelt's current Supreme Court troubles:

Judges of the United States Courts, at the age of 70, after having served 10 years, may retire upon full pay. In the past, many judges have availed themselves of this privilege. Some, however, have remained upon the bench long beyond the time that they are able to adequately discharge their duties, and in consequence the administration of justice has suffered. I suggest an act providing that when any judge of a federal court below the Supreme Court fails to avail himself of the privilege of retiring now granted by law, that the President be required, with the advice and consent of the Senate, to appoint another judge, who would preside over the affairs of the court and have precedence over the older one. This will insure at all times the presence of a judge sufficiently active to discharge promptly and adequately the duties of the court.[93]The content of McReynolds's proposal and the bill later submitted by Roosevelt were so similar to each other that it is thought the most probable source of the idea.[94] Roosevelt and Cummings also relished the opportunity to hoist McReynolds by his own petard.[95] McReynolds, having been born in 1862,[96] had been in his early fifties when he wrote his 1914 proposal, but was well over seventy when Roosevelt's plan was set forth.

Bill

Contents

The provisions of the bill adhered to four central principles:

- allowing the President to appoint one new, younger judge for each federal judge with 10 years service who did not retire or resign within six months after reaching the age of 70 years;

- limitations upon the number of judges the President could appoint: no more than six Supreme Court justices, and no more than two on any lower federal court, with a maximum allocation between the two of 50 new judges just after the bill is passed into law;

- that lower-level judges be able to float, roving to district courts with exceptionally busy or backlogged dockets; and

- lower courts be administered by the Supreme Court through newly created "proctors".[97]

The latter provisions were the result of lobbying by the energetic and reformist judge William Denman of the Ninth Circuit Court who believed the lower courts were in a state of disarray and that unnecessary delays were affecting the appropriate administration of justice.[98][99] Roosevelt and Cummings authored accompanying messages to send to Congress along with the proposed legislation, hoping to couch the debate in terms of the need for judicial efficiency and relieving the backlogged workload of elderly judges.[100]

The choice of date on which to launch the plan was largely determined by other events taking place. Roosevelt wanted to present the legislation before the Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments on the Wagner Act cases, scheduled to begin on February 8, 1937; however, Roosevelt also did not want to present the legislation before the annual White House dinner for the Supreme Court, scheduled for February 2.[101] With a Senate recess between February 3–5, and the weekend falling on February 6–7, Roosevelt had to settle for February 5.[101] Other pragmatic concerns also intervened. The administration wanted to introduce the bill early enough in the Congressional session to make sure it passed before the summer recess, and, if successful, to leave time for nominations to any newly-created bench seats.[101]

Public Reaction

After the proposed legislation was announced, public reaction was split. Since the Supreme Court was generally conflated with the U.S. Constitution itself,[102] the assault against the Court brushed up against this wider public reverence.[103] Roosevelt's personal involvement in selling the plan managed to mitigate this hostility. In a speech at the Democratic Victory Dinner on March 4, Roosevelt called for party loyalists to support his plan.

Roosevelt followed this up with his ninth Fireside chat on March 9, in which he made his case directly to the public. In his address, Roosevelt decried the Supreme Court's majority for "reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there, and which were never intended to be there".[104] He also argued directly that the Bill was needed to overcome the Supreme Court's opposition to the New Deal, stating that the nation had reached a point where it "must take action to save the Constitution from the Court, and the Court from itself".[104]

Through these interventions, Roosevelt managed briefly to earn favorable press for his proposal.[105] In general, however, the overall tenor of reaction in the press was negative. A series of Gallup Polls conducted between February and May 1937 showed that the public opposed the proposed bill by a fluctuating majority. By late March it had become clear that the President's personal abilities to sell his plan were limited:

Over the entire period, support averaged about 39%. Opposition to Court packing ranged from a low of 41% on 24 March to a high of 49% on 3 March. On average, about 46% of each sample indicated opposition to President Roosevelt's proposed legislation. And it is clear that, after a surge from an early push by FDR, the public support for restructuring the Court rapidly melted.[106]

Concerted letter-writing campaigns to Congress against the bill were launched, with opinion tallying against the bill nine-to-one. Bar associations nationwide followed suit as well, lining up in opposition to the bill.[107] Roosevelt's own Vice President John Nance Garner expressed disapproval of the bill, holding his nose and giving a thumbs down from the rear of the Senate chamber.[108] The editorialist William Allen White characterized Rooselvet's actions in a column on February 6 as an "... elaborate stage play to flatter the people by a simulation of frankness while denying Americans their democratic rights and discussions by suave avoidance - these are not the traits of a democratic leader.[109]

Reaction against the bill also spawned the National Committee to Uphold Constitutional Government, which was launched in February 1937 by three leading opponents of the New Deal. Frank E. Gannett, a newspaper magnate, provided both money and publicity. Two other founders, Amos Pinchot, a prominent lawyer from New York, and Edward Rumely had both been Roosevelt supporters who had soured on the President's agenda. Rumely directed an effective and intensive mailing campaign to drum up public opposition to the measure. Among the original members of the Committee were James Truslow Adams, Charles Coburn, John Haynes Holmes, Dorothy Thompson, Samuel S. McClure, Mary Dimmick Harrison, and Frank A. Vanderlip. The Committee's membership reflected the bipartisan opposition to the bill, especially among better educated and wealthier constituencies.[110] As Gannett explained, "we were careful not to include anyone who had been prominent in party politics, particularly in the Republican camp. We preferred to have the Committee made up of liberals and Democrats, so that we would not be charged with having partisan motives."[111]

The Committee made a determined stand against the Judiciary bill. It distributed more than 15 million letters condemning the plan. They targeted specific constituencies: farm organization, editors of agricultural publications, and individual farmers. They also distributed material to 161,000 lawyers, 121,000 doctors, 68,000 business leaders, and 137,000 clergymen. Pamphleteering, press releases and trenchantly worded radio editorials condemning the bill also formed part of the onslaught in the public arena.[112]

House action

Traditionally, legislation proposed by the administration first goes before the House of Representatives. However, Roosevelt failed to consult Congressional leaders before announcing the bill, which stopped cold any chance of passing the bill in the House.[113] House Judiciary Committee chairman Hatton W. Sumners refused to endorse the bill, actively chopping it up within his committee in order to block the bill's chief effect of Supreme Court expansion.[113] Finding such stiff opposition within the House, the administration arranged for the bill to be taken up in the Senate.[113]

Congressional Republicans deftly decided to remain silent on the matter, denying congressional Democrats the opportunity to use them as a unifying force.[114] Republicans then watched from the sidelines as the Democratic party split itself in the ensuing Senate fight.

Senate hearings

Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson. Entrusted by President Roosevelt to secure the court reform bill's passage, his unexpected death doomed the proposed legislation.

Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson. Entrusted by President Roosevelt to secure the court reform bill's passage, his unexpected death doomed the proposed legislation.

The administration began making its case for the bill before the Senate Judiciary Committee on March 10, 1937. Attorney General Cummings' testimony was grounded on four basic complaints of the administration:

- the reckless use of injunctions by the courts to pre-empt the operation of New Deal legislation;

- aged and infirm judges who declined to retire;

- crowded dockets at all levels of the federal court system; and

- the need for a reform which would infuse "new blood" in the federal court system.[115]

Administration advisor Robert H. Jackson testified next, attacking the Supreme Court's alleged misuse of judicial review and the ideological perspective of the majority.[115] Further administration witnesses were grilled by the committee, so much so that after two weeks less than half the administration's witnesses had been called.[115] Exasperated by the stall tactics they were meeting on the committee, administration officials decided to call no further witnesses; it later proved to be a tactical blunder, allowing the opposition to indefinitely drag-on the committee hearings.[115] Further setbacks for the administration occurred in the failure of farm and labor interests to align with the administration.[116]

However, once the bill's opposition had gained the floor, it pressed its upper hand, continuing hearings as long as public sentiment against the bill remained in doubt.[117] Of note for the opposition was the testimony of Harvard University law professor Erwin Griswold.[118] Specifically attacked by Griswold's testimony was the claim made by the administration that Roosevelt's court expansion plan had precedent in U.S. history and law.[118] While it was true the size of the Supreme Court had been expanded since the founding in 1789, it had never been done for reasons similar to Roosevelt's.[118] The following table lists all the expansions of the court:

Year Size Enacting Legislation Comments 1789 6 Judiciary Act of 1789 Original court with Chief Justice & five associate justices; two justices for each of the three circuit courts. (1 Stat. 73) 1801 5 Judiciary Act of 1801 Lameduck Federalists, at end of President John Adams's administration, greatly expand federal courts and reduce the number of associate justices¹ to four in order to dominate the judiciary and hinder judicial appointments by incoming President Thomas Jefferson.[119] (2 Stat. 89) 1802 6 Judiciary Act of 1802 Judiciary Act of 1801 repealed by Democratic-Republicans; no seat on the court actually abolished. (2 Stat. 132) 1807 7 Seventh Circuit Act Created a new circuit court for OH, KY, & TN; Jefferson appoints the new associate justice. (2 Stat. 420) 1837 9 Eighth & Ninth Circuits Act Signed by President Andrew Jackson on his last full day in office; Jackson nominates two associate justices, both confirmed; one declines appointment. New President Martin Van Buren then appoints the second. (5 Stat. 176) 1863 10 Tenth Circuit Act Created Tenth Circuit to serve CA and OR; added associate justice to serve it. (12 Stat. 794) 1866 7 Judicial Circuits Act Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase lobbied for this reduction.¹ The Radical Republican Congress took the occasion to overhaul the courts to reduce the influence of former Confederate States. (14 Stat. 209) 1869 9 Judiciary Act of 1869 Set Court at current size, reduced burden of riding circuit by introducing intermediary circuit court justices. (16 Stat. 44) Notes 1. Because federal justices serve during "good behavior", reductions in a federal court's size are accomplished only through either abolishing the court or attrition—i.e., a seat is abolished only when it becomes vacant. However, the Supreme Court cannot be abolished. As such, the actual size of the Supreme Court during a contraction may remain larger than the law provides until well after that law's enactment. Another event damaging to the administration's case was a letter authored by Chief Justice Hughes to Senator Burton Wheeler, which directly contradicted Roosevelt's claim of an overworked Supreme Court turning down over 85 percent of certiorari petitions in an attempt to keep up with their docket.[120] The truth of the matter, according to Hughes, was that rejections typically resulted from the defective nature of the petition, not due to the court's docket load.[120]

White Monday

On March 29, 1937, the court handed down three decisions upholding New Deal legislation, two of them unanimous: West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish,[7] Wright v. Vinton Branch,[121] and Virginia Railway v. Federation.[122][123] The Wright case upheld a new Frazier-Lemke Act which had been redrafted to meet the Court's objections in the Radford case; similarly, Virginia Railway case upheld labor regulations for the railroad industry, and is particularly notable for its foreshadowing of how the Wagner Act cases would be decided as the National Labor Relations Board was modeled on the Railway Labor Act contested in the case.[123]

West Coast Hotel v. Parrish

Main article: The switch in time that saved nineHowever, the Parrish case received the most attention, and later became an integral part of the "switch in time" narrative of conventional history.[124] In the case, the court divided along the same lines it had in the Tipaldo case, only this time around Roberts voted to overrule the Adkins precedent as the case brief specifically asked the court to reconsider its prior decision. Further, the decision worked to hinder Roosevelt's push for the court reform bill, further reducing what little public support there was for change in the Supreme Court.[123]

Roberts had voted to grant certiorari to hear the Parrish case before the election of 1936.[125] Oral arguments occurred on December 16 and 17, 1936, with counsel for Parrish specifically asking the court to reconsider its decision in Adkins v. Children's Hospital,[77] which had been the basis for striking down a New York minimum wage law in Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo[76] in the late spring of 1936.[8]

Roberts, however, indicated his desire to overturn Adkins immediately after oral arguments on Dec. 17, 1936.[8] The initial conference vote on Dec. 19, 1936 was split 4-4; with this even division on the Court, the holding of the Washington Supreme Court, finding the minimum wage statute constitutional, would stand.[126] The eight voting justices anticipated Justice Stone—absent due to illness—would be the fifth vote necessary for a majority opinion affirming the constitutionality of the minimum wage law.[126] As Chief Justice Hughes desired a clear and strong 5-4 affirmation of the Washington Supreme Court's judgment, rather than a 4-4 default affirmation, he convinced the other justices to wait until Stone's return before both deciding and announcing the case.[126]

President Roosevelt announced his court reform bill on February 5, 1937, the day of the first conference vote after Stone's February 1, 1937 return to the bench. Roosevelt later made his justifications for the bill to the public on March 9, 1937 during his 9th Fireside Chat. The Court's opinion in Parrish was not published until March 29, 1937, after Roosevelt's radio address. Chief Justice Hughes wrote in his autobiographical notes that Roosevelt's court reform proposal "had not the slightest effect on our [the court's] decision," but due to the delayed announcement of its decision the Court was characterized as retreating under fire.[127]

Bill's failure

Van Devanter retires

May 18, 1937 witnessed two setbacks for the administration. First, Associate Justice Willis Van Devanter—encouraged by the restoration of full-salary pensions under the March 1, 1937[67][128][129] Supreme Court Retirement Act[130]—announced his intent to retire on June 2, 1937, the end of the term.[131] This undercut one of Roosevelt's chief complaints against the court—he had not been given an opportunity in the entirety of his first term[4] to make even a nomination to the high court.[131] It also presented Roosevelt with a personal dilemma: he had already long ago promised the first court vacancy to Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson.[131] As Roosevelt had based his attack of the court upon the ages of the justices, appointing the 65 year old Robinson would belie Roosevelt's stated goal of infusing the court with younger blood.[132] Further, Roosevelt worried about whether Robinson could be trusted on the high bench; while Robinson was considered to be Roosevelt's New Deal "marshal" and was regarded as a progressive of the stripe of Woodrow Wilson,[133][134][135] he was a conservative Democrat on some issues too.[132] Finally, Van Devanter's retirement alleviated pressure to reconstitute a more politically-friendly court.

Committee report

The second setback occurred in the Senate Judiciary Committee action that day on Roosevelt's court reform bill.[136] First, an attempt at a compromise amendment which would have allowed the creation of only two additional seats was defeated 10–8.[136] Next, a motion to report the bill favorably to the floor of the Senate also failed 10–8.[136] Then, a motion to report the bill "without recommendation" failed by the same margin, 10–8.[136] Finally, a vote was taken to report the bill adversely, which passed 10–8.[136]

On June 14, the committee issued a scathing report that called FDR's plan "a needless, futile and utterly dangerous abandonment of constitutional principle... without precedent or justification".[137][138]

Public support for the President's plan, which had never been particularly strong, dissipated quickly in the aftermath of these developments.

Floor debate

Entrusted with ensuring the bill's passage, Robinson began his attempt to get the votes necessary to pass the bill.[139] In the meantime, he worked to finish another compromise which would abate Democratic opposition to the bill.[140] Ultimately devised was the Hatch-Logan amendment, which resembled Roosevelt's plan, but with changes in some details: the age limit for appointing a new coadjutor was increased to 75, and appointments of such a nature were limited to one per calendar year.[140]

The Senate opened debate on the substitute proposal on July 2.[141] Robinson led the charge, holding the floor for two days.[142] Procedural measures were used to limit debate and prevent any potential filibuster.[142] By July 12, Robinson had begun to show signs of strain, leaving the Senate chamber complaining of chest pains.[142]

Death of Robinson and defeat

On July 14, 1937 a housemaid found Robinson dead of a heart attack in his apartment, the Congressional Record at his side.[142] With Robinson gone so too were all hopes of the bill's passage.[143] Roosevelt further alienated his party's Senators when he decided not to attend Robinson's funeral in Little Rock, Arkansas.

On returning to Washington, D.C., Vice President John Nance Garner informed Roosevelt, "You are beat. You haven't got the votes."[144] On July 22, the Senate voted 70–20 to send the judicial-reform measure back to committee, where the controversial language was stripped by explicit instruction from the Senate floor.[145]

By July 29, 1937, the Senate Judiciary Committee—at the behest of new Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley—had produced a revised Judicial Procedures Reform Act.[146] This new legislation met with the previous bill's goal of revising the lower courts, but without providing for new federal judges or justices.

Congress passed the revised legislation, and Roosevelt signed it into law, on August 26.[147] This new law required that:

- parties-at-suit provide early notice to the federal government of cases with constitutional implications;

- federal courts grant government attorneys the right to appear in such cases;

- appeals in such cases be expedited to the Supreme Court;

- any constitutional injunction would no longer be enforced by one federal judge, but rather three; and

- such injunctions would be limited to a sixty day duration.[146]

Consequences

A political fight which began as a conflict between the President and the Supreme Court turned into a battle between Roosevelt and the recalcitrant members of his own party in the Congress.[11] The political consequences were wide-reaching, extending beyond the narrow question of judicial reform to implicate the political future of the New Deal itself. Not only was bipartisan support for Roosevelt's agenda largely dissipated by the struggle, the overall loss of political capital in the arena of public opinion was also significant.[11]

As Michael Parrish has written, "the protracted legislative battle over the Court-packing bill blunted the momentum for additional reforms, divided the New Deal coalition, squandered the political advantage Roosevelt had gained in the 1936 elections, and gave fresh ammunition to those who accused him of dictatorship, tyranny, and fascism. When the dust settled, FDR had suffered a humiliating political defeat at the hands of Chief Justice Hughes and the administration's Congressional opponents."[148][149]

With the retirement of Justice Willis Van Devanter, the Court's composition began to move solidly in support of Roosevelt's legislative agenda. By the end of 1941, following the deaths of Justices Benjamin N. Cardozo (1938) and Pierce Butler (1939), and the retirements of Van Devanter (1937), George Sutherland (1938), Louis Brandeis (1939), James Clark McReynolds (1941), and Charles Evans Hughes (1941), only two Justices (former Associate Justice, by then promoted to Chief Justice, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Associate Justice Owen Roberts) remained from the Court Roosevelt inherited in 1933.

As former Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist observed:

“ President Roosevelt lost the Court-packing battle, but he won the war for control of the Supreme Court ... not by any novel legislation, but by serving in office for more than twelve years, and appointing eight of the nine Justices of the Court. In this way the Constitution provides for ultimate responsibility of the Court to the political branches of government. [Yet] it was the United States Senate - a political body if there ever was one - who stepped in and saved the independence of the judiciary ... in Franklin Roosevelt's Court-packing plan in 1937.[150] ” Timeline

Year Date Case Cite Vote Holding Event 1934 Jan 8 Home Building & Loan Association v. Blaisdell 290 U.S. 398 (1934) 5–4 Minnesota's suspension of creditor's remedies constitutional Mar 5 Nebbia v. New York 291 U.S. 502 (1934) 5–4 New York's regulation of milk prices constitutional 1935 Jan 7 Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan 293 U.S. 388 (1935) 8–1 National Industrial Recovery Act, §9(c) unconstitutional Feb 18 Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. 294 U.S. 240 (1935) 5–4 Gold Clause Cases: Congressional abrogation

of contractual gold payment clauses constitutionalNortz v. United States 294 U.S. 317 (1935) 5–4 Perry v. United States 294 U.S. 330 (1935) 5–4 May 6 Railroad Retirement Bd. v. Alton R. Co. 295 U.S. 330 (1935) 5–4 Railroad Retirement Act unconstitutional May 27 Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States 295 U.S. 495 (1935) 9–0 National Industrial Recovery Act unconstitutional Louisville Joint Stock Land Bank v. Radford 295 U.S. 555 (1935) 9–0 Frazier-Lemke Act unconstitutional Humphrey's Executor v. United States 295 U.S. 602 (1935) 9–0 President may not remove FTC commissioner without cause 1936 Jan 6 United States v. Butler 297 U.S. 1 (1936) 6–3 Agricultural Adjustment Act unconstitutional Feb 17 Ashwander v. TVA 297 U.S. 288 (1936) 8–1 Tennessee Valley Authority constitutional Apr 6 Jones v. SEC 298 U.S. 1 (1936) 6–3 SEC rebuked for "Star Chamber" abuses May 18 Carter v. Carter Coal Company 298 U.S. 238 (1936) 5–4 Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935 unconstitutional May 25 Ashton v. Cameron County Water Improvement Dist. No. 1 298 U.S. 513 (1936) 5–4 Municipal Bankruptcy Act of 1934 ruled unconstitutional June 1 Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo 298 U.S. 587 (1936) 5–4 New York's minimum wage law unconstitutional Nov 3 Roosevelt electoral landslide ("As Maine goes, so goes Vermont" - James Farley) Dec 16 Oral arguments heard on West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish Dec 17 Associate Justice Owen Roberts indicates his vote to overturn Adkins v. Children's Hospital, upholding Washington state's

minimum wage statute contested in Parrish1937 Feb 5 Final conference vote on West Coast Hotel Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 ("JPRB37") announced Feb 8 Supreme Court begins hearing oral arguments on Wagner Act cases Mar 9 "Fireside chat" regarding national reaction to JPRB37 Mar 29 West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish 300 U.S. 379 (1937) 5–4 Washington state's minimum wage law constitutional Wright v. Vinton Branch 300 U.S. 440 (1937) 9–0 New Frazier-Lemke Act constitutional Virginian Railway Co. v. Railway Employees 300 U.S. 515 (1937) 9–0 Railway Labor Act constitutional Apr 12 NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. 301 U.S. 1 (1937) 5–4 National Labor Relations Act constitutional NLRB v. Fruehauf Trailer Co. 301 U.S. 49 (1937) 5–4 NLRB v. Friedman-Harry Marks Clothing Co. 301 U.S. 58 (1937) 5–4 Associated Press v. NLRB 301 U.S. 103 (1937) 5–4 Washington Coach Co. v. NLRB 301 U.S. 142 (1937) 5–4 May 18 "Horseman" Willis Van Devanter announces his intent to retire May 24 Steward Machine Company v. Davis 301 U.S. 548 (1937) 5–4 Social Security tax constitutional Helvering v. Davis 301 U.S. 619 (1937) 5–4 Jun 2 Van Devanter retires Jul 14 Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson dies Jul 22 JPRB37 referred back to committee by a vote of 70–20 to strip "court packing" provisions Aug 19 Senator Hugo Black sworn in as Associate Justice References

Notes

- ^ Parrish, Michael E. (2002). The Hughes Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc.. p. 24. ISBN 9781576071979.

- ^ a b Epstein, at 451.

- ^ a b Leuchtenburg, at 115ff.

- ^ a b March 4, 1933 – January 20, 1937. For the mismatched start and end dates on the term, see the Twentieth Amendment.

- ^ http://www.mhric.org/fdr/chat9.html

- ^ Winfield, Betty (1990). FDR and the news media. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 104. ISBN 0252016726.

- ^ a b 300 U.S. 379 (1937)

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 413.

- ^ White, at 308.

- ^ Ryfe, David Michael (1999). "Franklin Roosevelt and the fireside chats". The Journal of Communication 49 (4): 80–103. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02818.x. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119063612/abstract.

- ^ a b c d Leuchtenburg, at 156–61.

- ^ Epstein, at 440.

- ^ a b Oliver Wendell Holmes: law and the inner self, G. Edward White pg. 469

- ^ McKenna, at 35–36, 335–36.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 20–21.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 24–25.

- ^ McKenna, at 14–16.

- ^ Schlesinger, at 261.

- ^ Jenson, Carol E. (1992). "New Deal". In Hall, Kermit L.. Oxford Companion to the United States Supreme Court. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E. (June 2005). "Charles Evans Hughes: The Center Holds". North Carolina Law Review 83: 1187–1204. "Some scholars disapprove of the terms 'conservative' and 'liberal,' or 'right, center, and left,' when applied to judges because it may suggest that they are no different from legislators; but the private correspondence of members of the Court makes clear that they thought of themselves as ideological warriors. In the fall of 1929, Taft had written one of the Four Horsemen, Justice Butler, that his most fervent hope was for 'continued life of enough of the present membership ... to prevent disastrous reversals of our present attitude. With Van [Devanter] and Mac [McReynolds] and Sutherland and you and Sanford, there will be five to steady the boat ....' Six counting Taft."

- ^ a b c White, at 167–70.

- ^ 252 U.S. 416 (1920)

- ^ Gillman, Howard (2000). "Living Constitution". Macmillan Reference USA. http://www.novelguide.com/a/discover/eamc_04/eamc_04_01539.html. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ White, at 204–05.

- ^ a b c Cushman, at 5–7.

- ^ White, at 158-163.

- ^ a b c White, at 203–04.

- ^ a b Leuchtenburg, at 84.

- ^ 290 U.S. 398 (1934)

- ^ 291 U.S. 502 (1934)

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 26.

- ^ Nebbia v. New York, 291 U.S. 502, 524 (1934).

- ^ 293 U.S. 388 (1935)

- ^ "National Industrial Recovery Act". National Archives and Records Administration. 1933. http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=66&page=transcript. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ a b http://calvert.wustl.edu/PolSci3103.fall04/newdealcases.html

- ^ a b Urofsky, at 676–78.

- ^ Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388, 432 (1935) (“If the citizen is to be punished for the crime of violating a legislative order of an executive officer, or of a board or commission, due process of law requires that it shall appear that the order is within the authority of the officer, board, or commission, and, if that authority depends on determinations of fact, those determinations must be shown.”).

- ^ http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/mlc03

- ^ Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co., 294 U.S. 240 (1935); Nortz v. United States, 294 U.S. 317 (1935); Perry v. United States, 294 U.S. 330 (1935).

- ^ Wilson, Thomas Frederick (1992). The Power "to Coin" Money: The Exercise of Monetary Powers by the Congress. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. p. 209. ISBN 9780873327954. http://books.google.com/?id=VIAbb1cKqp4C.

- ^ a b c d e f g McKenna, at 56–66.

- ^ 5 U.S. 137 (1803)

- ^ Perry v. United States, 294 U.S. 330, 354 (1935) (“The action is for breach of contract. As a remedy for breach, plaintiff can recover no more than the loss he has suffered and of which he may rightfully complain. He is not entitled to be enriched.”).

- ^ 295 U.S. 330 (1935)

- ^ a b c d e f Leuchtenburg, at 27–39.

- ^ McKenna, at 66–73.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 96–103.

- ^ 295 U.S. 602 (1935)

- ^ a b Leuchtenburg, at 60.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 61–62.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 69.

- ^ a b c d Urofsky, at 678–81.

- ^ 295 U.S. 555 (1935)

- ^ a b McKenna, at 100–01.

- ^ 295 U.S. 495 (1935)

- ^ a b c d White, at 111–14.

- ^ 196 U.S. 375 (1905)

- ^ a b Urofsky, at 679.

- ^ 234 U.S. 342 (1914)

- ^ McKenna, at 104–05.

- ^ a b Leuchtenburg, at 78–81.

- ^ 272 U.S. 52 (1926)

- ^ McKenna, at 113.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 114–15.

- ^ a b c d Urofsky, at 681–83.

- ^ 297 U.S. 1 (1936)

- ^ a b http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma02/volpe/newdeal/timeline_text.html

- ^ a b Urofsky, at 683–84.

- ^ McKenna, at 197–98.

- ^ McKenna, at 202–03.

- ^ http://www.oyez.org/cases/1901-1939/1935/1935_636/

- ^ 298 U.S. 238 (1936)

- ^ 128 U.S. 1 (1888)

- ^ 156 U.S. 1 (1895)

- ^ a b c d e http://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/abaj23&div=193&id=&page=

- ^ a b 298 U.S. 587 (1936)

- ^ a b 261 U.S. 525 (1923)

- ^ Levinson, Sanford V. (1973). "The Democratic Faith of Felix Frankfurter". Stanford Law Review 25 (3): 430–448. doi:10.2307/1227769. JSTOR 1227769.

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 209–13, 408–12.

- ^ White, 220-222.

- ^ Urofsky, at 694.

- ^ Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo, 298 U.S. 587, 604-05 (1936) (“The petition for the writ sought review upon the ground that this case is distinguishable from that one [Adkins]. No application has been made for reconsideration of the constitutional question there decided. ... He is not entitled, and does not ask, to be heard upon the question whether the Adkins case should be overruled. He maintains that it [the New York minimum wage law] may be distinguished on the ground that the statutes are vitally dissimilar.”).

- ^ a b Cushman, at 92–104.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 106.

- ^ a b c Leuchtenburg, at 83–85.

- ^ McKenna, at 146.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 157–68.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 94.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 98.

- ^ McKenna, at 169.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 110.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 118–19.

- ^ Annual Report of the Attorney General (Washington, D.C.: 1913), 10.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 120.

- ^ McKenna, at 296.

- ^ McReynolds, James Clark, Federal Judicial Center, visited January 28, 2009.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 124.

- ^ Frederick, David C. (1994). Rugged Justice: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and the American West, 1891-1941. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 181. ISBN 0520083814. "Before long, Denman had championed the creation of additional Ninth Circuit judgeships and reform of the entire federal judicial system. In testimony before Congress, speeches to bar groups, and letters to the president, Denman worked tirelessly to create an administrative office for the federal courts, to add fifty new district judges and eight new circuit judges nationwide, and to end unnecessary delays in litigation. Denman's zeal for administrative reform, combined with the deeply divergent views among the judges on the legality of the New Deal, gave the internal workings of the Ninth Circuit a much more political imprimatur than it had had in its first four decades."

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 113–14; McKenna, at 155–57.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, at 125.

- ^ a b c Leuchtenburg, at 129.

- ^ Perry, Barbara; Abraham, Henry (2004). "Franklin Roosevelt and the Supreme Court: A New Deal and a New Image". In Shaw, Stephen K.; Pederson, William D.; Williams, Frank J.. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Transformation of the Supreme Court. London: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 13–35. ISBN 0765610329.

- ^ Kammen, Michael G. (2006). A Machine that Would Go of Itself: The Constitution in American Culture. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. pp. 8–9; 276–281. ISBN 141280583X.

- ^ a b "Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary". Fireside Chats. 1937-03-09. No. 9.

- ^ Caldeira, Gregory A. (Dec. 1987). "Public Opinion and The U.S. Supreme Court: FDR's Court-Packing Plan". The American Political Science Review 81 (4): 1139–1153. doi:10.2307/1962582. JSTOR 1962582.

- ^ Caldeira, 1146-47

- ^ McKenna, at 303–14.

- ^ McKenna, at 285.

- ^ Hinshaw, David (2005). A Man from Kansas: The Story of William Allen White. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. pp. 258–259. ISBN 1417983485.

- ^ Richard Polenberg, "The National Committee to Uphold Constitutional Government, 1937–1941", The Journal of American History, Vol. 52, No. 3 (1965-12), at 582–98.

- ^ Frank Gannett, "History of the Formation of the N.C.U.C.G. and the Supreme Court Fight", August 1937, Frank Gannett Papers, Box 16 (Collection of Regional History, Cornell University). Cited in Polenburg at 583.

- ^ Polenberg, at 586.

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 314–17.

- ^ McKenna, at 320–24.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 356–65.

- ^ McKenna, at 381.

- ^ McKenna, at 386–96.

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 396–401.

- ^ May, Christopher N.; Ides, Allan (2007). Constitutional Law: National Power and Federalism (4th ed.). New York, NY: Aspen Publishers. pp. 8.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 367–72.

- ^ 300 U.S. 440 (1937)

- ^ 300 U.S. 515 (1937)

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 420–22.

- ^ Burkhauser, Richard V.; Finegan, T. Aldrich (1989). "The Minimum Wage and the Poor: The End of a Relationship". Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (Bloomington, IN: Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management) 8 (1): 53–71. doi:10.2307/3324424. JSTOR 3324424. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/114108757/abstract. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ^ McKenna, at 412-13.

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 414.

- ^ McKenna, at 419.

- ^ Columbia Law Review, Vol. 37, No. 7 (Nov., 1937). pg. 1212

- ^ http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0418_0208_ZD.html

- ^ Ball, Howard. Hugo L. Black: Cold Steel Warrior. Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 0-19-507814-4. Page 89.

- ^ a b c McKenna, at 453–57.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 458.

- ^ http://www.oldstatehouse.com/exhibits/virtual/governors/the_progressive_era/robinson.aspx

- ^ http://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=121

- ^ http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/People_Leaders_Robinson.htm

- ^ a b c d e McKenna, at 460–61.

- ^ McKenna, at 480–87.

- ^ Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Reorganization of the Federal Judiciary, S. Rep. No. 711, 75th Congress, 1st Session, 1 (1937).

- ^ McKenna, at 319.

- ^ a b McKenna, at 486–91.

- ^ McKenna, at 496.

- ^ a b c d McKenna, at 498–505.

- ^ McKenna, at 505.

- ^ McKenna, at 516.

- ^ McKenna, at 519–21.

- ^ a b Black, Conrad (2003). Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 417. ISBN 9781586481841.

- ^ Pederson, William D. (2006). Presidential Profiles: The FDR Years. New York: Facts on File, Inc.. p. 284. ISBN 9780816053685.

- ^ Parrish, Michael (1983). "The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the American Legal Order". Washington Law Review 59: 737.

- ^ McKenna, at 522ff.

- ^ Rehnquist, William H. (2004). "Judicial Independence Dedicated to Chief Justice Harry L. Carrico: Symposium Remarks". University of Richmond Law Review 38: 579–596. http://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/urich38&id=591.

Sources

- Baker, Leonard (1967). Back to Back: The Duel Between FDR and the Supreme Court. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Caldeira, Gregory A. (Dec. 1987). "Public Opinion and The U.S. Supreme Court: FDR's Court-Packing Plan". The American Political Science Review 81 (4): 1139–1153. doi:10.2307/1962582. JSTOR 1962582.

- Cushman, Barry (1998). Rethinking the New Deal Court: The Structure of a Constitutional Revolution. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195115321.

- Epstein, Lee; Walker, Thomas G. (2007). Constitutional Law for a Changing America: Institutional Powers and Constraints (6th ed.). Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 9781933116815.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. (1995). The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195111316.

- McKenna, Marian C. (2002). Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Constitutional War: The Court-packing Crisis of 1937. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823221547.

- Minton, Sherman Reorganization of Federal Judiciary; speeches of Hon. Sherman Minton of Indiana in the Senate of the United States, July 8 and 9, 1937. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1937.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. (2003). The Politics of Upheaval: the Age of Roosevelt, 1935–1936. 3. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780618340873.

- Shaw, Stephen K., et al., eds. (2004). Shaw, Stephen K.; Pederson, William D.; Williams, Frank J.. eds. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Transformation of the Supreme Court. London: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765610329.

- Urofsky, Melvin I.; Finkelman, Paul (2002). A March of Liberty: A Constitutional History of the United States. 2 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195126372.

- White, G. Edward (2000). The Constitution and the New Deal. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674008311.

External links

- FDR's Fireside Chat on the bill

- 1990 Eyewitness Account of Law Clerk Joseph L. Rauh, Jr. (Link live as of September 15, 2008)

Categories:- 1937 in law

- 1937 in American politics

- Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- History of the Supreme Court of the United States

- History of the United States (1918–1945)

- Legal history of the United States

- New Deal

- Political history of the United States

- Supreme Court of the United States

- United States proposed federal legislation

- United States federal judiciary legislation

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.