- Dunston Power Station

-

Dunston power station

Dunston B Power Station

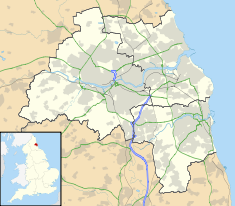

Viewed from southwestLocation of Dunston power station Official name Dunston A and B power stations Country England Location Dunston Coordinates 54°57′37″N 1°39′32″W / 54.96028°N 1.65889°WCoordinates: 54°57′37″N 1°39′32″W / 54.96028°N 1.65889°W Status Demolished Construction began 1908 (A station)

1930 (B station)

1947 (Gas turbine)Commission date 1910 (A station)

1933-51 (B station)

1955 (Gas turbine)Decommission date 1975-81 Owner(s) Newcastle-upon-Tyne Electric Supply Company

(1910–1947)

British Electricity Authority

(1948–1954)

Central Electricity Authority

(1954–1957)

Central Electricity Generating Board

(1957–1981)Power station information Primary fuel Coal Secondary fuel Natural gas Generation units A station:

Two 7.2 MW AEG, one 6.25 MW Brown Boveri, one 13.2 MW Brown Boveri and later one 15 MW C. A. Parsons and Company gas turbine

B station:

Six 50 MW C. A. Parsons and CompanyPower generation information Installed capacity 1910: 33.85 MW

1951: 333.85 MW

1955: 348.85 MW

1981: 98 MW- Sometimes confused with the nearby Stella power stations.

Dunston Power Station refers to a pair of adjacent coal-fired power stations in the North East of England, now demolished. They were built on the south bank of the River Tyne, in the western outskirts of Dunston in Gateshead. The two stations were built on a site which is now occupied by the MetroCentre. The first power station built on the site was known as Dunston A Power Station, and the second, which gradually replaced it between 1933 and 1950, was known as Dunston B Power Station. The A Station was, in its time, one of the largest in the country, and as well as burning coal had early open cycle gas turbine units. The B Station was the first of a new power station design, and stood as a landmark in the Tyne for over 50 years. From the A Station's opening in 1910 until the B Station's demolition in 1986, they collectively operated from the early days of electricity generation in the United Kingdom, through the industry's nationalisation, and up until a decade before its privatisation.

Dunston A had a generating capacity of 48.85 megawatts (MW) in 1955, and Dunston B had a generating capacity of 300 MW. Electricity from the stations powered an area covering Northumberland, County Durham, Cumberland, Yorkshire and as far north as Galashiels in Scotland.[1]

Contents

Dunston A Power Station

History

With the expansion of the electric supply industry in the early 1900s, power stations were built to supply homes with electric lighting. Around Newcastle upon Tyne this led to the construction of power stations at Lemington, The Close and Carville. Two supply companies built the stations, the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Electric Supply Company (NESCo) to the east of Newcastle, and the Newcastle and District Electric Lighting Company (DisCo) to the west.[2] To meet an increasing demand for electricity, NESCo commissioned Dunston Power Station (later Dunston A Power Station) on the Derwent Haugh, a large flood plain to the west of Gateshead, to balance the supply of the Newcastle area with the Carville station.[3][4] Construction of the new station began in 1908, the work undertaken by the company of Sir Robert McAlpine. They completed the construction in the short time of 20 months, and this was to be their first in a large number of power station constructions, following the decline of the railway industry.[5][6] In 1910, the station was opened and began generating electricity.[4][7]

Design and specification

The station was of a similar design to other local power stations at Carville and Lemington, and was a large triple-gabled brick building.[3][8] However Dunston A was built several years after the other local stations, and so because of advances in power station design, was larger and was able to produce more electricity than the others. The station was originally equipped with two turbo-alternators rated at 7.2 megawatts (MW), made by AEG of Germany, and two turbo alternators rated at 6.25 MW and 13.2 MW, made by Brown Boveri of Switzerland, for a total generating capacity of 33.85 MW.[3][9] The turbo alternators were supplied with steam from 24 coal burning Babcock and Wilcox marine water-tube boilers.

Low temperature carbonisation plant

In 1925, NESCo set up separate plant at the power station for the low temperature carbonisation treatment of coal, before being burned in boilers and the steam used for electricity generation. The treatment plant was manufactured by Babcock & Wilcox, and set up in a self-contained boiler house which contained four boilers, four retorts and pulverising mills. The building was also fitted with gas-stripping and by-product plants. The carbonising plant could handle up to 100 tonnes of coal per day, while its boilers produced 78,000 lb of steam per hour.[10] This plant was extended in 1931.[11]

Gas turbine plant

Between 1947[3] and November 1955,[12] the station was extended, and a 15 MW Parsons gas turbine turbo alternator was installed, bringing the capacity of the station up to 48.85 MW.[3][13][14] The gas was supplied by pipe line from the Norwood Coke Works, 1.5 mi (2.4 km) away in the Team Valley.[3][15]

Dunston B Power Station

As part of a transition from the 40 Hertz (Hz) system, used by the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Electric Supply Company, to the 50 Hz system, used by the new UK National Grid, which took place in 1932, a new power station was built to replace the A power station.[16]

Design and specification

The new Dunston B Power Station was designed by consulting engineers Merz & McLellan. Its design was different from the design of other power stations at the time because it enclosed the machinery in a steel frame clad with glass.[1] This was a departure from the usual power station designs, which normally enclosed the machinery in a concrete or brick wall. Dunston B is thought to be the first power station in the UK and possibly even the world to be built in this way.[4] The station was also the first in the world to use metal clad switchgear at a voltage as high as 66,000 V.[17]

Construction of the new power station started in 1930, but the Second World War delayed its full completion until 1951. The station was opened in stages throughout its construction, as generating units were able to be put into production while the other sections were still under construction. The first units were commissioned in January 1933.[7][14]

The new station had a total capacity of 300 megawatts (MW). This was provided by six 50 MW generating sets, which were made by C. A. Parsons and Company. These were the largest machines ever constructed under Charles Algernon Parsons' supervision.[14][18]

The station's units were the first application of super reheated steam in steam turbines in the world, an advancement which gave them a heat consumption of only 9,280 BTU per kilowatt hour, the most efficient system in the UK. In 1939 the station was said to be "at the head of all the Power Stations in Great Britain as regards thermal efficiency."[19] The station remained one of Britain's most efficient systems until the 1950s.[1][14]

The stations' buildings were around 100 ft (30 m) tall. Flue gasses were discharged through six 250 ft (76 m) tall chimneys, one for each of the station's six generating units.[20] The station was fitted with two electrostatic precipitators in 1953, one completed in June that year and the other in September. They were fitted to reduce smoke and pollution from the station.[21]

Operations

The plant's water system was cooled by using the nearby River Tyne, rather than using a cooling tower system.[1] Coal for the station was supplied from various coal mines in the North Durham coalfields, and was brought to the station by train, on what was a freight only line. Since the station's closure, this line has been upgraded for use by passenger trains and is now used as part of the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway.[1] Once delivered to the station, coal was shunted by CEGB No. 15 "Eustace Forth", which was built by Robert Stephenson and Hawthorns in 1942, and No. 13 "The Barra", which was built by Hawthorn Leslie & Company in 1928. These two engines are now stored at Shildon Locomotion Museum and Tanfield Railway respectively.[22][23]

Various ships disposed of the station's ash waste, by carrying the fly ash down the river and dumping it in the North Sea. These vessels included "Bobby Shaftoe", "Bessie Surtees" and "Hexhamshire Lass", which were also used by the nearby Stella power stations; as well as a number of tugs towing hopper barges, including "Mildred".[24][25]

Closure, demolition and present

There is now a Costco cash and carry on the site of the power station.

- See also MetroCentre (shopping centre)

In its time, Dunston B Power Station ranked consistently in England's leading stations, both in terms of thermal efficiency and cost per unit of electricity.[14] However, the station eventually became outdated, and notification of its partial closure was given in October 1975, with some units being closed the following October.[26] It was then only used as a stand-by station, operating only at peak electrical demand times. Finally, after some units having been in operation for about 40 years, the station ceased to generate electricity on 26 October 1981. At the time of closure, only 98 MW of the station's capacity was in use.[27]

The station was demolished in 1986 to make way for the MetroCentre, which became Europe's largest shopping and leisure centre.[28] The land on which the MetroCentre was built was bought for only £100,000, because the site was water-logged and had been used for dumping ash produced by the power station. American warehouse club chain Costco have since built a store on the actual site of the power station.[29] The power station's large indoor sub-station still stands alongside it, as the only trace of the site's former use.

Due to the closure of Dunston power station, along with the later closures of the power stations at Stella and Blyth, the northern part of North East England has became heavily dependent upon the National Grid for electrical supply. However, in the south of the region there are still two large power stations at Hartlepool and Teesside, meaning that the south of the region does not depend upon the National Grid for electrical supply as much as the north of the region.[30]

Visual and cultural impact

The power station's six chimneys were a prominent local landmark, visible from along a 8.6-mile (13.8 km) stretch of the Tyne valley running from Bensham in Gateshead to Heddon-on-the-Wall in Northumberland.[31]

When in operation, the B station briefly featured in Get Carter, a 1971 crime film starring Michael Caine. Dunston B appears as part of the films backdrop, viewed from the now demolished Frank Street in Benwell, as the funeral cortège of the main character's brother Frank leaves a house on the street.[29][32]

The station was also a popular subject for photographers. It featured in the work of documentary and press photographer Bert Hardy, who photographed it from Benwell, using it as a backdrop whilst photographing a mother and child.[33] It was also photographed by Welsh documentary photographer Jimmy Forsyth, as part of his Scotswood Road collection.[34]

See also

- List of power stations in England

- Timeline of the UK electricity supply industry

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- Electricity Act 1947

- Electricity Act 1957

- Northern Electric

References

- ^ a b c d e "Dunston Power Station". Whickham Web Wanderers. u3a. http://www.webwanderers.org/2006/08/dunston_power_station.html. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- ^ "North Eastern Electricity Board". The National Archives. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/records.aspx?cat=183-dueb&cid=0#0. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Dunston Power Station". The Electrician (James Gray) 87: 259. 1947. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=CaFMAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&ei=3kYaTJLeGeSTOJzk3ZcK&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDcQ6AEwAQ. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ a b c "History of Dunston". http://www.gateshead-history.com/. http://www.gateshead-history.com/dunston.html. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Jux, Frank (August 1974). "Sir Robert McAlpine & Sons Ltd: The End Of An Era". The Industrial Railway Record. http://www.irsociety.co.uk/Archives/55/McAlpine.htm. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Institution of Civil Engineers (1937). Minutes of proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 240. p. 3. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=U281AAAAMAAJ&q=%22dunston%22+%22power+station%22+1908&dq=%22dunston%22+%22power+station%22+1908&hl=en&ei=AsgUTP-JFcmTOPjawJYM&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAA. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Structure Details". Newcastle University. 26 March 2004. http://sine.ncl.ac.uk/view_structure_information.asp?struct_id=1702. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "000841:Power Station Dunston unknown not dated". Newcastle Libraries. 25 August 2009. http://www.flickr.com/photos/newcastlelibraries/4076194546/in/set-72157622716457015/. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Hughes, Thomas Parke (1993). Networks of power: electrification in Western society, 1880–1930. p. 456. ISBN 0801846145. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=g07Q9M4agp4C&hl=en&ei=ZPYUTKfUMNuSOPy0hfUL&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ "Low-Temperature Carbonisation at Dunston". Durham Mining Museum. November 1928. http://www.dmm-gallery.org.uk/colleng/281a-01.htm. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "A Notable Low-Temperature Plant". Durham Mining Museum. April 1931. http://www.dmm-gallery.org.uk/colleng/3104-01.htm. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ The Electrical Journal. 155. 1955. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=3oQnAAAAMAAJ&hl=en&ei=bF4aTOLTJ6OjOK2q1ZsK&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CEMQ6AEwBTgU. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Gas Turbines". Electrical Times 123: 68. 1953. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ellOAAAAMAAJ&hl=en&ei=beoUTI-GIIOKOMnf6fIL&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAA. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e The Electricity Council. "Electricity Supply in the United Kingdom" (PDF). pp. 55, 67, 75. https://ntmm.org/~nt/elecpow/history/electricity_supply_in_the_uk__a_chronology_ocrnopic.pdf. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Dr D G Edwards. "By-Product Coking Plants in Britain: An Outline History" (PDF). The Coke Oven Managers' Association. p. 7. http://www.coke-oven-managers.org/PDFs/edwards.pdf. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Pears, Brian (23 February 2003). "Norfolk to Northumberland". Rootsweb. http://newsarch.rootsweb.com/th/read/NORTHUMBRIA/2003-02/1046007772. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ North-Eastern Electric Supply Company Limited 1889-1948. Newcastle upon Tyne: T.M Grierson Ltd. March 1948.

- ^ Scaife, Garrett (2000). From galaxies to turbines: science, technology, and the Parsons family. CRC Press. p. 507. ISBN 0750305827. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=BeMjgxsifcQC&hl=en&ei=IooaTIjWKdOg_gbHv_iRCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDcQ6AEwAQ. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Parsons, R.H. (1939). "X". The Early Days of the Power Station Industry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 183.

- ^ Marks, Percy L. (2008). Chimneys and Flues – Domestic and Industrial. pp. 92–98. ISBN 1443772941.

- ^ Mr. Joynson-Hicks; Mr. Popplewell (11 May 1953). "Power Station, Dunston-on-Tyne (Electrostatic Precipitators)". Hansard. http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1953/may/11/power-station-dunston-on-tyne#S5CV0515P0_19530511_CWA_53. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ "Steam Locomotive, named Eustace Forth". nrm.org.uk. http://www.nrm.org.uk/OurCollection/LocomotivesAndRollingStock/CollectionItem.aspx?objid=1978-7007&pageNo=22. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Dunston Power Station No. 13 'The Barra'". steamlocomotive.info. http://www.steamlocomotive.info/vlocomotive.cfm?Display=4563. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Ian (3 March 2003). "Hardworking Bessie". Evening Chronicle. http://www.wiki-north-east.co.uk/article.aspx?id=777839. Retrieved 3 July 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Tyne Tugs". Aspects of South Shields. http://website.lineone.net/~d.ord/Tugs%20and%20Ships.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-29.[dead link]

- ^ Mr. Eadie (5 December 1975). "Power Stations". Hansard. http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1975/dec/05/power-stations#S5CV0901P0_19751205_CWA_441. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ Mr. Redmond (16 January 1984). "Coal-fired Power Stations". Hansard. http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1984/jan/16/coal-fired-power-stations#S6CV0052P0_19840116_CWA_281. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ Henderson, Tony (19 March 2007). "A bridge to a better and greener future". http://www.wiki-north-east.co.uk/. The Journal. http://www.wiki-north-east.co.uk/article.aspx?id=1647694. Retrieved 2008-11-20.[dead link]

- ^ a b Noah, Sherna (4 October 2004). "Caine No 1". Sunday Sun. http://www.sundaysun.co.uk/whats-on-newcastle-north-east/cinema-film-reviews/2004/10/04/caine-no-1-79310-14715856/. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Bone, Anthony; Morag Hunter, Bill Wilkinson (1999). "Energy for a new century" (PDF). North East England: Government Offices for the English Regions. pp. 50, 106. http://www.gos.gov.uk/nestore/docs/envandrural/energy/north_east_energy_strategy.pdf. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Geographer's A–Z Street Atlas. Newcastle upon Tyne, Sunderland, Durham (Map). 1 : 15840. A to Z (1980 ed.). p. 36–37, 54–60.

- ^ "Film Locations Get Carter". http://www.reelstreets.com/public/p_film_page.php?film=get_carter. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ "Newcastle Street". Getty Images. http://www.gettyimages.de/detail/2638477/Hulton-Archive. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ "Dunston Power Station, November 1955". Amber Online. http://www.amber-online.com/exhibitions/scotswood-road/exhibits/dunston-power-station-november-1955. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

External links

- iSee Gateshead – Various photographs from the construction of the B Station

- Appeal – An appeal for former employees of the power station, after a former worker at the station died from peritoneal mesothelioma a rare form of cancer caused by exposure to asbestos fibers.

- YouTube - Footage from a train passing the power station in 1983

Electricity generation in North East England Generating

sitesActiveProposed/FutureActiveLynemouth · WiltonClosedBerwick upon Tweed · Blyth · Carville · Chopwell Colliery · Close · Consett · Darlington · Derwenthaugh Coke Works · Dunston · Forth Banks · Hebburn · Horden Colliery · Lemington · Mainsforth Colliery · Manors · Morrison Busty Colliery · Neptune Bank · Newburn Steelworks · North Tees · Ouston Colliery · Pandon Dene · Philadelphia · South Shore Road · South Shields · Stella · Sunderland · Vane Tempest Colliery · WhinfieldProposed/FutureEston Grange (Gasification)Refused/ShelvedBlyth Clean Coal · KepierActiveProposed/FutureConocoPhillips Teesside · Thor CogenerationRefusedNewburnActiveClosedActiveRefusedActiveWiltonActiveTeesside · Path Head landfillClosedFutureNorth Eastern Energy Recovery Centre · Wilton 11RefusedActiveBlyth Harbour · Blyth Offshore · Broom Hill · Great Eppleton · Hare Hill · High Sharpley · High Volts · Holmside Hall · Kirkheaton · Langley Park · Tow Law · Trimdon Grange · Walkway · West DurhamFutureBlyth Harbour (repowering) · Butterwick Moor · Great Eppleton (repowering) · Haswell Moor · Kiln Pit Hill · Lynemouth · Royal Oak · TeessideProposedBarmoor South · Green Rigg · Kielder · Moorsyde · Ray Hill · South Sharpley · Steadings · Teeswind North · The Isles · Todd Hill · West Ancroft · Wingates

Organisations

and personnelA. Reyrolle & Company · C. A. Parsons and Company · Northern Powergrid · Charles Algernon Parsons · Charles Hesterman Merz · Clarke Chapman · John Theodore Merz · L J Couves & Partners · Merz & McLellan · NaREC · Newcastle and District Electric Lighting Company · North Eastern Electric Supply Company · Northern Electric · Northern Engineering Industries · Pre-nationalisation North East electric power companiesCategories:- Coal-fired power stations in England

- Power stations in North East England

- Demolished power stations in the United Kingdom

- Demolished buildings and structures in England

- 1910 establishments in England

- 1981 disestablishments

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.