- Minimum wage in the United States

-

As of July 24, 2009[update], the federal minimum wage in the United States is $7.25 per hour. Some states and municipalities have set minimum wages higher than the federal level (see List of U.S. minimum wages), with the highest state minimum wage being $8.67 in Washington. Some U.S. territories (such as American Samoa) are exempt. Some types of labor are also exempt, and tipped labor must be paid a minimum of $2.13 per hour, as long as the hourly wage plus tipped income result in a minimum of $7.25 per hour.

The July 24, 2009 increase was the last of three steps of the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2007. The wage increase was signed into law on May 25, 2007 as a rider to the U.S. Troop Readiness, Veterans' Care, Katrina Recovery, and Iraq Accountability Appropriations Act, 2007. The bill also contains almost $5 billion in tax cuts for small businesses.

Among those paid by the hour in 2009, 980,000 were reported as earning exactly the prevailing Federal minimum wage. Nearly 2.6 million were reported as earning wages below the minimum. Together, these 3.6 million workers with wages at or below the minimum made up 4.9 percent of all hourly-paid workers.[1]

Contents

Earlier U.S. minimum wages laws

In 1912, Massachusetts organized a commission to recommend non-compulsory minimum wages for women and children. Within eight years, at least thirteen U.S. states and the District of Columbia would pass minimum wage laws.[2] The Lochner era United States Supreme Court consistently invalidated compulsory minimum wage laws. Such laws, said the court, were unconstitutional for interfering with the ability of employers to freely negotiate appropriate wage contracts with employees.[3]

The first attempt at establishing a national minimum wage came in 1933, when a $0.25 per hour standard was set as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act. However, in the 1935 court case Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (295 U.S. 495), the United States Supreme Court declared the act unconstitutional, and the minimum wage was abolished.

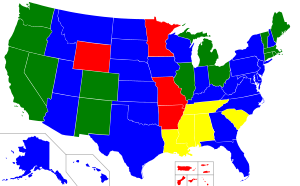

Minimum Wage by U.S. state and U.S. territory (American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands), as of July 24, 2009.

Minimum Wage by U.S. state and U.S. territory (American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands), as of July 24, 2009. States with minimum wage rates higher than the Federal rateStates and territories with minimum wage rates the same as the Federal rateStates with no minimum wage lawStates and territories with minimum wage rates lower than the Federal rate

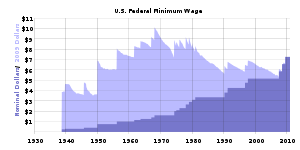

States with minimum wage rates higher than the Federal rateStates and territories with minimum wage rates the same as the Federal rateStates with no minimum wage lawStates and territories with minimum wage rates lower than the Federal rateThe minimum wage was re-established in the United States in 1938 (pursuant to the Fair Labor Standards Act), once again at $0.25 per hour ($3.77 in 2009 dollars). The minimum wage had its highest purchasing value ever in 1968, when it was $1.60 per hour ($9.86 in 2010 dollars). From January 1981 to April 1990, the minimum wage was frozen at $3.35 per hour, then a record-setting wage freeze. From September 1, 1997 through July 23, 2007, the federal minimum wage remained constant at $5.15 per hour, breaking the old record.

Congress then gave states the power to set their minimum wages above the federal level. As of July 1, 2010[update], fourteen states had done so.[4] Some government entities, such as counties and cities, observe minimum wages that are higher than the state as a whole. One notable example of this is Santa Fe, New Mexico, whose $9.50 per hour minimum wage was the highest in the nation,[5][6][7] until San Francisco increased its minimum wage to $9.79 in 2009.[8] Another device to increase wages, living wage ordinances, generally apply only to businesses that are under contract to the local government itself.

On November 7, 2006, voters in six states (Arizona, Colorado, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, and Ohio) approved statewide increases in the state minimum wage. The amounts of these increases ranged from $1 to $1.70 per hour and all increases are designed to annually index to inflation.[9]

Some politicians in the United States advocate linking the minimum wage to the Consumer Price Index, thereby increasing the wage automatically each year based on increases to the Consumer Price Index. So far, Ohio, Oregon, Missouri, Vermont and Washington have linked their minimum wages to the consumer price index. Minimum wage indexing also takes place each year in Florida, San Francisco, California, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Minimum wage jobs rarely include health insurance coverage,[10][11] although that is changing in some parts of the United States where the cost of living is high, such as California.[citation needed]

According to a paper by Fuller and Geide-Stevenson, 45.6% of American economists in the year 2000 agreed that a minimum wage increases unemployment among unskilled and young workers, while 27.9% agree with this statement but with provisos.[12] As a policy question in 2006, the minimum wage has—to some extent—split the economics profession with just under half believing it should be eliminated and a slightly smaller percentage believing it should be increased, leaving rather few in the middle.

Some idea of the empirical problems of this debate can be seen by looking at recent trends in the United States. The minimum wage fell about 29% in real terms between 1979 and 2003. For the median worker, real hourly earnings have increased since 1979; however, for the lowest deciles, there have been significant decreases in the real wage without much decrease in the rate of unemployment. Some argue that a declining minimum wage might reduce youth unemployment (since these workers are likely to have fewer skills than older workers).[13]

Overall, there is no consensus between economists about the effects of minimum wages on youth employment, although empirical evidence suggests that this group is most vulnerable to high minimum wages.[14]

Classical economics argues that the demand for labor increases as the price of labor falls. Each firm must evaluate the potential to make a profit from each worker hired; if the workers cost less, then more profit can be made from hiring more workers at a lower price. Therefore, by setting a lower boundary to wages, a minimum wage law prevents firms from offering jobs below the minimum and increases unemployment.

In Keynesian economics the perspective is very different. Although employers and workers set their wages in nominal terms, they are unable to predict the exact purchasing power of those wages. The value of the real wage can only be known "ex post" -- long after the workers have been paid. Neither unions nor government authorities know the real wage and can only approximate it by regulating the nominal wage. The real wage is the purchasing power of wages when adjusted for inflation, but inflation--the purchasing power of money and therefore of wages--depends on total levels of investment.

Investment, in its turn, depends upon consumption, and consumption depends upon the marginal propensity to consume (savings rate) across all income categories. In an "underconsumption" scenario, the transfer of income from entrepreneurs and rentiers (those with higher incomes) to the working class (via union wage agreements and minimum wages) can actually lead to an increase in total consumption and higher demand for goods--leading to increased employment. However, the resulting higher price levels may spur several forms of political and institutional responses that blunt or negate this tendency. For one, inflation tends to transfer income from bond holders (rentiers) to wage earners. For another, entrepreneurs may, under conditions of oligopoly be able to blunt the effect of rising wages by using their market power to raise prices fast enough to prevent real gains among workers. And finally, the central bank may intervene to defend price levels by increasing interest rates, which will tend to curb investment and decrease the demand for labor.

Without choosing from among these perspectives, it is sufficient to say that minimum wage increases are unlikely to have a simple linear effect on employment. The interconnection of price levels, central bank policy, wage agreements, total aggregate demand creates a situation where the conclusions to be drawn from macroeconomic analysis will be highly influenced by the underlying assumptions.[15]

Jobs affected by the minimum wage

The jobs that are most likely to be directly affected by the Minimum Wage are the ones that pay a wage close to the minimum.

According to the May 2006 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,[16] the four lowest-paid occupational sectors in May 2006 (when the Federal Minimum Wage was $5.15 per hour) were the following:

Sector Workers Employed Median Wage Mean Wage Mean Annual Food Preparation and Serving Related Occupations 11,029,280 $7.90 $8.86 $18,430 Farming, Fishing, and Forestry Occupations 450,040 $8.63 $10.49 $21,810 Personal Care and Service Occupations 3,249,760 $9.17 $11.02 $22,920 Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance Occupations 4,396,250 $9.75 $10.86 $22,580 Two years later, in May 2008, when the Federal Minimum Wage was $5.85 per hour and was about to increase to $6.55 per hour in July 2008, these same sectors were still the lowest-paying, but their situation (according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data)[17] was:

Sector Workers Employed Median Wage Mean Wage Mean Annual Food Preparation and Serving Related Occupations 11,438,550 $8.59 $9.72 $20,220 Farming, Fishing, and Forestry Occupations 438,490 $9.34 $11.32 $23,560 Personal Care and Service Occupations 3,437,520 $9.82 $11.59 $24,120 Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance Occupations 4,429,870 $10.52 $11.72 $24,370 In 2006, workers in the following 13 individual occupations received, on average, a median hourly wage of less than $8.00 per hour:

Occupation Workers Employed Median Wage Mean Wage Mean Annual Gaming Dealers 82,960 $7.08 $8.18 $17,010 Waiters and Waitresses 4,312,930 $3.14 $4.27 $11,190 Combined Food Preparation and Serving Workers, Including Fast Food 2,461,890 $7.24 $7.66 $15,930 Dining Room and Cafeteria Attendants and Bartender Helpers 401,790 $7.36 $7.84 $16,320 Cooks, Fast Food 612,020 $7.41 $7.67 $15,960 Dishwashers 502,770 $7.57 $7.78 $16,190 Ushers, Lobby Attendants, and Ticket Takers 101,530 $7.64 $8.41 $17,500 Counter Attendants, Cafeteria, Food Concession, and Coffee Shop 524,410 $7.76 $8.15 $16,950 Hosts and Hostesses, Restaurant, Lounge, and Coffee Shop 340,390 $7.78 $8.10 $16,860 Shampooers 15,580 $7.78 $8.20 $17,050 Amusement and Recreation Attendants 235,670 $7.83 $8.43 $17,530 Bartenders 485,120 $7.86 $8.91 $18,540 Farmworkers and Laborers, Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse 230,780 $7.95 $8.48 $17,630 In 2008, only two occupations paid a median wage less than $8.00 per hour:

Occupation Workers Employed Median Wage Mean Wage Mean Annual Gaming Dealers 91,130 $7.84 $9.56 $19,890 Combined Food Preparation and Serving Workers, Including Fast Food 2,708,840 $7.90 $8.36 $17,400 According to the May 2009 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,[18] the lowest-paid occupational sectors in May 2009 (when the Federal Minimum Wage was $7.25 per hour) were the following:

Sector Workers Employed Median Wage Mean Wage Mean Annual Gaming Dealers 86,900 $8.19 $9.76 $20,290 Combined Food Preparation and Serving Workers, Including Fast Food 2,695,740 $8.28 $8.71 $18,120 Waiters and Waitresses 2,302,070 $8.50 $9.80 $20,380 Dining Room and Cafeteria Attendants and Bartender Helpers 402,020 $8.51 $9.09 $18,900 Cooks, Fast Food 539,520 $8.52 $8.76 $18,230 See also

References

- ^ "Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers: 2009". U.S. Department of Labor. Accessed September 8, 2010. http://www.bls.gov/cps/minwage2009.htm.

- ^ William P. Quigley, "'A Fair Day's Pay For A Fair Day's Work': Time to Raise and Index the Minimum Wage", 27 St. Mary's L. J. 513, 516 (1996)

- ^ Id. at 518.

- ^ Minimum Wage Laws in the States. From the United States Department of Labor. Employment Standards Administration. Wage and Hour Division. The source page has a clickable US map with current and projected state-by-state minimum wage rates for each state.

- ^ "Ordinance 2003-8". City of Santa Fe. http://www.santafenm.gov/cityclerks/living-wage-2003-8.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ "City's minimum pay requirement expands to small businesses; state minimum kicks in". By Julie Ann Grimm. Dec. 31, 2007. The Santa Fe New Mexican.

- ^ Santa Fe Living Wage Network.

- ^ Selna, Robert (December 26, 2008). "S.F. minimum wage rises to $9.79 in 2009". San Francisco Chronicle. http://articles.sfgate.com/2008-12-26/bay-area/17131177_1_minimum-wage-prices-new-year.

- ^ ACORN and Unions Increase Working Wages Across the Country

- ^ Colliver, Victoria (August 29, 2010). "Health plans dwindle in U.S. Number of firms offering insurance drops as costs rise". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2005/09/15/BUG8OENLE61.DTL.

- ^ "The Family Connection". http://community.michiana.org/famconn/wrconper.html.

- ^ Fuller, Dan and Doris Geide-Stevenson (2003): Consensus Among Economists: Revisited, in: Journal of Economic Review, Vol. 34, No. 4, Seite 369-387 (PDF)

- ^ "Minimum Wages and Youth Employment in France and the United States". Cornell. May 1997. http://instruct1.cit.cornell.edu/~jma7/minimum-wages-youth.pdf.

- ^ Ghellab, Youcef (1998): Minimum Wages and Youth Unemployment, ILO Employment and Training Papers 26 (PDF)

- ^ For a review article which analyzes the classical, Keynesian, and underconsumptionist approaches to wages, see Sidney Weintraub, "A Macroeconomic Approach to the Theory of Wages," The American Economic Review, Vol. 46, No. 5 (Dec., 1956), pp. 835-856

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics May 2006 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates United States

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics - May 2008 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates United States

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics May 2009 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates United States

External links

- Federal Minimum Wage. United States Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division. As of July 24, 2009.

- Minimum Wages for Tipped Employees. United States Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division. As of January 1, 2010.

- The Minimum Wage: Information, Opinion, Research. Brock Haussamen - Professor Emeritus at Raritan Valley Community College. Last updated July 19, 2010.

- History of the FLSA and Federal Minimum Wage

- U.S. Minimum Wage History. Oregon State University - Wealth and Poverty (Anth 484). Last updated July 26, 2010.

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.