- Wolof language

-

Wolof Spoken in  Mauritania

MauritaniaRegion West Africa Ethnicity Wolof, Lebou Native speakers 4.2 million (2006)

L2 speakers: ?Language family Niger–Congo- Atlantic–Congo

- Senegambian

- Wolof–Nyun

- Wolof

- Wolof–Nyun

- Senegambian

Official status Official language in None Regulated by CLAD (Centre de linguistique appliquée de Dakar) Language codes ISO 639-1 wo ISO 639-2 wol ISO 639-3 either:

wol – Wolof

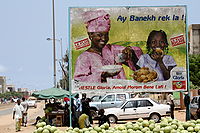

wof – Gambian WolofWolof is a language spoken in Senegal, The Gambia, and Mauritania, and is the native language of the Wolof people. Like the neighbouring languages Serer and Fula, it belongs to the Atlantic branch of the Niger–Congo language family. Unlike most other languages of Sub-Saharan Africa, Wolof is not a tonal language.

Wolof is the most widely spoken language in Senegal, spoken not only by members of the Wolof ethnic group (approximately 40 percent of the population) but also by most other Senegalese. Note however that, this figure is misleading because other tribes who have been Wolofized and speak the Wolof language are added to this figure when in actual fact they are not Wolofs at all.[1] Wolof dialects may vary between countries (Senegal and the Gambia) and the rural and urban areas. "Dakar-Wolof", for instance, is an urban mixture of Wolof, French, Arabic, and even a little English - spoken in Dakar, the capital of Senegal. "Wolof" is the standard spelling, and is a term that may also refer to the Wolof ethnic group or to things originating from Wolof culture or tradition. As an aid to pronunciation, some older French publications use the spelling "Ouolof"; for the same reason, some English publications adopt the spelling "Wollof", predominantly referring to Gambian Wolof. Prior to the 20th century, the forms "Volof", and "Olof" were used.

Wolof has had some influence on Western European languages. Banana is possibly a Wolof word in English[citation needed], and the English word yam is believed to be derived from Wolof/Fula nyami, "to eat food."

It should be stated that, the word "nyam" and its derivatives "nyami" attributed to the Wolof people or Fula here actually comes from the language of the Serer people, from the standard Serer-Sine word "gari ñam" (pronounced "gari nyam") meaning "to eat", from the Serer Kingdom of Sine. The Wolof people who have immigrated to another Serer Kingdom called the Kingdom of Saloum picked it up from the Serer people of Saloum (the indigenous people). In Serer Saloum, the word is "ñaam" (nyam) which means "to eat". Whilst in Serer-Sine (proper Serer) it is "gari ñam" (gari nyam) meaning "to eat", in Saloum it is merely shortened to "ñaam". The word derives from the proper Serer word "ñam" (nyam) which means "food". It is from that the Senegambian word "ñaambi" (cassava) originated from. These words are used by all Senegambians not just by the Serer people (the progenitors of these words), but also by the Wolof people, the Fula people, the Mandinka people etc.[2][3][4][5][6] The Serer people also being ancestors of the Wolof people as they are the ancestors of the Toucouleur people and Lebou people, their language has also been borrowed and diluted by these groups. "Cheikh Anta Diop had defended the hypothesis that the Wollofs were not originally a group apart but the result of a process of metissage so to speak of different ethnic groups: Serere, Lebou, Toucoulor, Mandinka and Sarahuli who, in their evolution i.e. the Wollofs, transformed themselves into an autonomous "tribe" with a strong capacity to assimilate, absorb or integrate with all other ethnic groups.[7] The Serer people also have an ancient tradition of farming not just millet and other crops but cassava ("ñaambi") as well.

Hip or hep (e.g., African-American's now clichéd "hip cat") is believed by many etymologists to derive from the Wolof hepicat, "one who has his eyes open" or "one who is aware".[8]

Contents

Geographical distribution

Wolof is spoken by more than 10 million people and about 40 percent (approximately 5 million people) of Senegal's population speak Wolof as their native language. Increased mobility, and especially the growth of the capital Dakar, created the need for a common language: today, an additional 40 percent of the population speak Wolof as a second or acquired language. In the whole region from Dakar to Saint-Louis, and also west and southwest of Kaolack, Wolof is spoken by the vast majority of the people. Typically when various ethnic groups in Senegal come together in cities and towns, they speak Wolof. It is therefore spoken in almost every regional and departmental capital in Senegal. Nevertheless, the official language of Senegal is French.

As stated above, great care should be taken when forming an opinion based on the figures prescribed here. These figures are misleading because other tribes who have been Wolofized and speak the Wolof language are added to this figure when in actual fact they are not Wolofs at all.[9] Furthermore, not only is Serer and Fula just like Wolof etc recognised and taught in schools, not everyone speaks or understands Wolof. There are Serers, Fulas, Mandinkas, Jolas etc who cannot speak or understand Wolof. Moreover, not only Wolof people live in cities and towns. There are cities and towns which are predominantly Serers just as there are cities and towns which are predominantly Wolofs. Furthermore, there are Wolof villages just as there are Serer villages.

In the Gambia, about three percent of the population speak Wolof as a first language, but Wolof has a disproportionate influence because of its prevalence in Banjul, the Gambia's capital, where 25 percent of the population use it as a first language. In Serrekunda, the Gambia's largest town, although only a tiny minority are ethnic Wolofs, approximately 10 percent of the population speaks and/or understands Wolof. The official language of the Gambia is English; Mandinka (40 percent), Wolof (7 percent) and Fula (15 percent) are as yet not used in formal education.

In Mauritania, about seven percent (approximately 185,000 people) of the population speak Wolof. There, the language is used only around the southern coastal regions. Mauritania's official language is Arabic; French is used as a lingua franca.

Classification

Wolof is one of the Senegambian languages, which are characterized by consonant mutation. It is often said to be closely related to Fulani due to a misreading by Wilson (1989) of the data in Sapir (1971) that has long been used to classify the Atlantic languages. However, Serere (2009, 2010) confirms Sapir's findings that Wolof is not close to Fulani; he finds the closest relatives of Wolof are several obscure languages along the Casamance River.[10]

Example phrases

This paragraph uses the exact orthography developed by the CLAD institute, which can be found in Arame Fal's dictionary (see bibliography below). For the literal translation, please note that Wolof does not have tenses in the sense of the Indo-European languages; rather, Wolof marks aspect and focus of an action. The literal translation given in the table below is an exact word-by-word translation in the original word order, where the meanings of the individual words are separated by dashes.

To listen to the pronunciation of some Wolof words, click here

Wolof English Literal translation into English (As)salaamaalekum !

Response: Maalekum salaam !This greeting is not Wolof—it is Arabic (used by Arabic speakers), but is commonly used.

Hello!

Response: Hello!(Arabic) peace be with you

Response: and with you be peaceNa nga def ? / Naka nga def ? / Noo def?

Response: Maa ngi fi rekkHow do you do? / How are you doing?

Response: I am fineHow - you (already) - do

Response: I here - be - here - onlyNaka mu ?

Response: Maa ngi fiWhat's up?

Response: I'm fineHow is it?

Response: I'm hereNumu demee? / Naka mu demee?/

Response: Nice / Mu ngi doxHow's it going?

Response: Fine / Nice / It's goingHow is it going?

Response: Nice (from English) / It's walking (going)Lu bees ?

Response: Dara (beesul)What's new?

Response: Nothing (is new)What is it that is new?

Response: Nothing/something (is not new)Ba beneen (yoon). See you soon (next time) Until - other - (time) Jërëjëf Thanks / Thank you It was worth it Waaw Yes Yes Déedéet No No Fan la ... am ? Where is a ...? Where - that which is - ... - existing/having Fan la fajkat am ? Where is a physician/doctor? Where - the one who is - heal-maker - existing/having Fan la ... nekk ? Where is the ...? Where - it which is - ... - found? Ana ...? Where is ...? Where is ...? Ana loppitaan bi? Where is the hospital? Where is - hospital - the? Noo tudd(a)* ? / Naka nga tudd(a) ?

Response: ... laa tudd(a) / Maa ngi tudd(a) ...(* Gambian Wolof has an <a> after word-ending doubled consonants )

What is your name?

Response: My name is ....What you (already) - being called?

Response: ... I (objective) - called / I am called ...It should be noted that the "Wolof words" prescribed in this table mostly derived from the Serer language which the Wolofs have borrowed and adopted. This borrowing is understandable since the Serers are the ancestors of the Wolofs.[11] Example of borrowed words include (but are not limited to):

Few words are definitely borrowed and corrupted from the Fula language "Jërë" (Jërëjëf) and the word "loppitaan" is obviously borrowed from the French word "L’hôpital".

Orthography and pronunciation

Note: Phonetic transcriptions are printed between brackets [] following the rules of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

The Latin-based orthography of Wolof in Senegal was set by government decrees between 1971 and 1985. The language institute "Centre de linguistique appliquée de Dakar" (CLAD) is widely acknowledged as an authority when it comes to spelling rules for Wolof.

Wolof is most often written in this orthography, in which phonemes have a clear one-to-one correspondence to graphemes.

(A traditional Arabic-based transcription of Wolof called Wolofal dates back to the pre-colonial period and is still used by many people.)

The first syllable of words is stressed; long vowels are pronounced with more time, but are not automatically stressed, as they are in English.

Vowels

Wolof adds diacritic marks to the vowel letters to distinguish between open and closed vowels. Example: "o" [ɔ] is open like (British) English "often", "ó" [o] is closed similar to the o-sound in English "most" (but without the u-sound at the end). Similarly, "e" [ɛ] is open like English "get", while "é" [e] is closed similar to the sound of "a" in English "gate" (but without the i-sound at the end).

Single vowels are short, geminated vowels are long, so Wolof "o" [ɔ] is short and pronounced like "ou" in (British) English "sought", but Wolof "oo" [ɔ:] is long and pronounced like the "aw" in (British) English "sawed". If a closed vowel is long, the diacritic symbol is usually written only above the first vowel, e.g. "óo", but some sources deviate from this CLAD standard and set it above both vowels, e.g. "óó".

The very common Wolof letter "ë" is pronounced [ə], like "a" in English "sofa".

Consonants

The characters (U+014B) Latin small letter eng "ŋ" and (U+014A) Latin capital letter eng "Ŋ" are used in the Wolof alphabet. They are pronounced like "ng" in English "hang".

The characters (U+00F1) Latin small letter n with tilde "ñ" and (U+00D1) Latin capital letter n with tilde "Ñ" are also used. They are pronounced like the same letter in Spanish "señor".

"c" is between "t" in English (of England) "fortune" and "ch" in English "choose", while "j" is between "d" in English (of England) "duke" and "j" in "June". "x" is like "ch" in German "Bach", while "q" is like "c" in English "cool". "g" is always like "g" in English "garden", and "s" is always like "s" in English "stop". "w" is as in "wind" and "y" as in "yellow".

Grammar

Notable characteristics

Pronoun conjugation instead of verbal conjugation

In Wolof, verbs are unchangeable words which cannot be conjugated. To express different tenses or aspects of an action, the personal pronouns are conjugated - not the verbs. Therefore, the term temporal pronoun has become established for this part of speech.

Example: The verb dem means "to go" and cannot be changed; the temporal pronoun maa ngi means "I/me, here and now"; the temporal pronoun dinaa means "I am soon / I will soon / I will be soon". With that, the following sentences can be built now: Maa ngi dem. "I am going (here and now)." - Dinaa dem. "I will go (soon)."

Conjugation with respect to aspect instead of tense

In Wolof, tenses like present tense, past tense, and future tense are just of secondary importance, they even play almost no role. Of crucial importance is the aspect of an action from the speaker's point of view. The most important distinction is whether an action is perfective, i.e., finished, or imperfective, i.e., still going on, from the speaker's point of view, regardless whether the action itself takes place in the past, present, or future. Other aspects indicate whether an action takes place regularly, whether an action will take place for sure, and whether an action wants to emphasize the role of the subject, predicate, or object of the sentence. As a result, conjugation is not done by tenses, but by aspects. Nevertheless, the term temporal pronoun became usual for these conjugated pronouns, although aspect pronoun might be a better term.

Example: The verb dem means "to go"; the temporal pronoun naa means "I already/definitely", the temporal pronoun dinaa means "I am soon / I will soon / I will be soon"; the temporal pronoun damay means "I (am) regularly/usually". Now the following sentences can be constructed: Dem naa. "I go already / I have already gone." - Dinaa dem. "I will go soon / I am just going to go." - Damay dem. "I usually/regularly/normally go."

If the speaker absolutely wants to express that an action took place in the past, this is not done by conjugation, but by adding the suffix -(w)oon to the verb. (Please bear in mind that in a sentence the temporal pronoun is still used in a conjugated form along with the past marker.)

Example: Demoon naa Ndakaaru. "I already went to Dakar."

Action verbs versus static verbs and adjectives

Consonant harmony

Gender

Wolof lacks gender-specific pronouns: there is one word encompassing the English 'he', 'she', and 'it'. The descriptors bu góor (male / masculine) or bu jigéen (female / feminine) are often added to words like xarit, 'friend', and rakk, 'younger sibling' in order to indicate the person's gender.

It should be noted that the word "góor" ("goor" or "gor") originated from the Serer language. These words orignated from the Serer words "o koor" or "goor" which means "man". "O kor" or "gor" also from the Serer language, means "husband". It is from this the Serer word "gorie" ("honour" or "honourable") comes. All these words and their derivatives are used by other Senegambians including the Wolof, but they all originated from the language of the Serer people.[17]

For the most part, Wolof does not have noun concord ("agreement") classes as in Bantu or Romance languages. But the markers of noun definiteness (usually called "definite articles" in grammatical terminology) do agree with the noun they modify. There are at least ten articles in Wolof, some of them indicating a singular noun, others a plural noun. In "City Wolof" (the type of Wolof spoken in big cities like Dakar), the article -bi is often used as a generic article when the actual article is not known.

Any loan noun from French or English uses –bi –- butik-bi, xarit-bi, 'the boutique, the friend'

Most Arabic or religious terms use –ji -- jumma-ji, jigéen-ji, 'the mosque, the girl'

Nouns referring to persons typically use -ki -- nit-ki, nit-ñi, 'the person, the people'

Miscellaneous articles: si, gi, wi, mi, li, yi.

Numerals

Cardinal numbers

The Wolof numeral system is based on the numbers "5" and "10". It is extremely regular in formation, comparable to Chinese. Example: benn "one", juróom "five", juróom-benn "six" (literally, "five-one"), fukk "ten", fukk ak juróom benn "sixteen" (literally, "ten and five one"), ñett-fukk "thirty" (literally, "three-ten"). Alternatively, "thirty" is fanweer, which is roughly the number of days in a lunar month (literally "fan" is day and "weer" is moon.)

0 tus / neen / zéro [French] / sero / dara ["nothing"] 1 benn 2 ñaar / yaar 3 ñett / ñatt / yett / yatt 4 ñeent / ñenent 5 juróom 6 juróom-benn 7 juróom-ñaar 8 juróom-ñett 9 juróom-ñeent 10 fukk 11 fukk ak benn 12 fukk ak ñaar 13 fukk ak ñett 14 fukk ak ñeent 15 fukk ak juróom 16 fukk ak juróom-benn 17 fukk ak juróom-ñaar 18 fukk ak juróom-ñett 19 fukk ak juróom-ñeent 20 ñaar-fukk 26 ñaar-fukk ak juróom-benn 30 ñett-fukk / fanweer 40 ñeent-fukk 50 juróom-fukk 60 juróom-benn-fukk 66 juróom-benn-fukk ak juróom-benn 70 juróom-ñaar-fukk 80 juróom-ñett-fukk 90 juróom-ñeent-fukk 100 téeméer 101 téeméer ak benn 106 téeméer ak juróom-benn 110 téeméer ak fukk 200 ñaari téeméer 300 ñetti téeméer 400 ñeenti téeméer 500 juróomi téeméer 600 juróom-benni téeméer 700 juróom-ñaari téeméer 800 juróom-ñetti téeméer 900 juróom-ñeenti téeméer 1000 junni / junne 1100 junni ak téeméer 1600 junni ak juróom-benni téeméer 1945 junni ak juróom-ñeenti téeméer ak ñeent-fukk ak juróom 1969 junni ak juróom-ñeenti téeméer ak juróom-benn-fukk ak juróom-ñeent 2000 ñaari junni 3000 ñetti junni 4000 ñeenti junni 5000 juróomi junni 6000 juróom-benni junni 7000 juróom-ñaari junni 8000 juróom-ñetti junni 9000 juróom-ñeenti junni 10000 fukki junni 100000 téeméeri junni 1000000 tamndareet / million Ordinal numbers

Ordinal numbers (first, second, third, etc.) are formed by adding the ending –éélu (pronounced ay-lu) to the cardinal number.

For example two is ñaar and second is ñaaréélu

The one exception to this system is “first”, which is bu njëk (or the adapted French word premier: përëmye)

1st bu njëk 2nd ñaaréélu 3rd ñettéélu 4th ñeentéélu 5th juróoméélu 6th juróom-bennéélu 7th juróom-ñaaréélu 8th juróom-ñettéélu 9th juróom-ñeentéélu 10th fukkéélu Personal pronouns

Temporal pronouns

Conjugation of the temporal pronouns

Situative (Presentative) (Present Continuous)

Terminative (Past tense for action verbs or present tense for static verbs)

Objective (Emphasis on Object)

Processive (Explicative and/or Descriptive) (Emphasis on Verb)

Subjective (Emphasis on Subject)

Neutral Perfect Imperfect Perfect Future Perfect Imperfect Perfect Imperfect Perfect Imperfect Perfect Imperfect 1st Person singular "I" maa ngi (I am+ Verb+ -ing)

maa ngiy naa (I + past tense action verbs or present tense static verbs)

dinaa (I will ... / future)

laa (Puts the emphasis on the Object of the sentence)

laay (Indicates a habitual or future action)

dama (Puts the emphasis on the Verb or the state 'condition' of the sentence)

damay (Indicates a habitual or future action)

maa (Puts the emphasis on the Subject of the sentence)

maay (Indicates a habitual or future action)

ma may 2nd Person singular "you" yaa ngi yaa ngiy nga dinga nga ngay danga dangay yaa yaay nga ngay 3rd Person singular "he/she/it" mu ngi mu ngiy na dina la lay dafa dafay moo mooy mu muy 1st Person plural "we" nu ngi nu ngiy nanu dinanu lanu lanuy danu danuy noo nooy nu nuy 2nd Person plural "you" yéena ngi yéena ngiy ngeen dingeen ngeen ngeen di dangeen dangeen di yéena yéenay ngeen ngeen di 3rd Person plural "they" ñu ngi ñu ngiy nañu dinañu lañu lañuy dañu dañuy ñoo ñooy ñu ñuy Note that many of the words stated in this table are borrowed from the language of the Serer people (Serer). Some of these borrowed words include (but not limited to):

- Maa

- Laa

- Laay

- Lay

- Yaa

- Yaay

- Ngay etc ...[18]

Words such as “dafa” and “dina” are obviously borrowed from Arabic

In urban Wolof it is common to use the forms of the 3rd person plural also for the 1st person plural.

It is also important to note that the verb follows certain temporal pronouns and precedes others.

Literature

The New Testament was translated into Wolof and published in 1987, second edition 2004, and in 2008 with some minor typographical corrections.[19]

The 1994 song '7 seconds' by Youssou N'Dour and Neneh Cherry is partially sung in Wolof.

References

- ^ African Sensus Analysis Project (ACAP). University of Pennsylvania. Ethnic Diversity and Assimilation in Senegal: Evidence from the 1988 Census by Pieere Ngom, Aliou Gaye and Ibrahima Sarr. 2000

- ^ Diktioneer Seereer-Angeleey (Serere-English Dictionary). Peace Corps – Senegal. First Edition, May 2010. Compiled by PCVs Bethany Arnold, Chris Carpenter, Guy Pledger, and Jack Brown.

- ^ CRETOIS, RP Léonce (1973). Dictionnaire sereer-français (différents dialectes) 48- Tome 1 AC. Dakar : Centre de Linguistique Appliquée de Dakar.

- ^ FAYE, Waly (1979). Etude morphosyntaxique du Sereer Singandum: parler de Jaxaaw et de Ňaaxar. Grenoble III.

- ^ FIONA, Mc Laughlin (1995). "Consonant Mutation in Sereer-Siin". In Studies in Afircan Linguistics, volume 23, Number 3. 1992-94, Los Angeles: University of California.

- ^ Léopold Sédar Senghor, (1943). Les classes nominales en wolof et les substantifs à initiales nasales. Journal de la société des Africanistes.

- ^ Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability. By Alhaji Ebou Momar Taal. 2010.

- ^ Holloway, Joseph E. The Impact of African Languages on American English. Slavery in America. Retrieved on 2006.10.05.

- ^ African Sensus Analysis Project (ACAP). University of Pennsylvania. Ethnic Diversity and Assimilation in Senegal: Evidence from the 1988 Census by Pieere Ngom, Aliou Gaye and Ibrahima Sarr. 2000

- ^ Such as Kobiana and Banyum. Guillaume Serere & Florian Lionnet 2010. "'Isolates' in 'Atlantic'". Language Isolates in Africa workshop, Lyon, Dec. 4

- ^ Senegambian Ethnic Groups: Common Origins and Cultural Affinities Factors and Forces of National Unity, Peace and Stability. By Alhaji Ebou Momar Taal. 2010.

- ^ Diktioneer Seereer-Angeleey (Serere-English Dictionary). Peace Corps – Senegal. First Edition, May 2010. Compiled by PCVs Bethany Arnold, Chris Carpenter, Guy Pledger, and Jack Brown.

- ^ CRETOIS, RP Léonce (1973). Dictionnaire sereer-français (différents dialectes ) 48- Tome 1 AC. Dakar : Centre de Linguistique Appliquée de Dakar.

- ^ Faye, Waly (1979). Etude morphosyntaxique du sereer singandum: parler de Jaxaaw et de Ňaaxar. Grenoble III.

- ^ FIONA, Mc Laughlin (1995). Consonant Mutation in Sereer-Siin. In Studies in Afircan Linguistics, volume 23, Number 3. 1992-94, Los Angeles: University of California.

- ^ Léopold Sédar Senghor (1943). Les classes nominales en wolof et les substantifs à initiales nasales. Journal de la société des Africanistes.

- ^ Diktioneer Seereer-Angeleey (Serere-English Dictionary). Peace Corps – Senegal. First Edition, May 2010. Compiled by PCVs Bethany Arnold, Chris Carpenter, Guy Pledger, and Jack Brown.

- ^ Diktioneer Seereer-Angeleey (Serere-English Dictionary). Peace Corps – Senegal. First Edition, May 2010. Compiled by PCVs Bethany Arnold, Chris Carpenter, Guy Pledger, and Jack Brown.

- ^ Biblewolof.com

Bibliography

- Linguistics

- Omar Ka: Wolof Phonology and Morphology. University Press of America, Lanham, Maryland, 1994, ISBN 0-8191-9288-0.

- Mamadou Cissé: « Graphical borrowing and African realities » in Revue du Musée National d'Ethnologie d'Osaka, Japan, June 2000.

- Mamadou Cissé: "Revisiter "La grammaire de la langue wolof" d'A. Kobes (1869), ou étude critique d'un pan de l'histoire de la grammaire du wolof.", in Sudlangues Sudlangues.sn, February 2005

- Leigh Swigart: Two codes or one? The insiders’ view and the description of codeswitching in Dakar, in Carol M. Eastman, Codeswitching. Clevedon/Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters, ISBN 1-85359-167-X.

- Fiona McLaughlin: Dakar Wolof and the configuration of an urban identity, Journal of African Cultural Studies 14/2, 2001, p. 153-172

- Gabriele Aïscha Bichler: Bejo, Curay und Bin-bim? Die Sprache und Kultur der Wolof im Senegal (mit angeschlossenem Lehrbuch Wolof), Europäische Hochschulschriften Band 90, Peter Lang Verlagsgruppe, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 2003, ISBN 3-631-39815-8.

- Grammar

- Pathé Diagne: Grammaire de Wolof Moderne. Présence Africaine, Paris, France, 1971.

- Pape Amadou Gaye: Wolof - An Audio-Aural Approach. United States Peace Corps, 1980.

- Amar Samb: Initiation a la Grammaire Wolof. Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire, Université de Dakar, Ifan-Dakar, Sénegal, 1983.

- Michael Franke: Kauderwelsch, Wolof für den Senegal - Wort für Wort. Reise Know-How Verlag, Bielefeld, Germany 2002, ISBN 3-89416-280-5.

- Michael Franke, Jean Léopold Diouf, Konstantin Pozdniakov: Le wolof de poche - Kit de conversation (Phrasebook/grammar with 1 CD). Assimil, Chennevières-sur-Marne, France, 2004 ISBN 978-2-7005-4020-8.

- Jean-Léopold Diouf, Marina Yaguello: J'apprends le Wolof - Damay jàng wolof (1 textbook with 4 audio cassettes). Karthala, Paris, France 1991, ISBN 2-86537-287-1.

- Michel Malherbe, Cheikh Sall: Parlons Wolof - Langue et culture. L'Harmattan, Paris, France 1989, ISBN 2-7384-0383-2 (this book uses a simplified orthography which is not compliant with the CLAD standards; a CD is available).

- Jean-Léopold Diouf: Grammaire du wolof contemporain. Karthala, Paris, France 2003, ISBN 2-84586-267-9.

- Fallou Ngom: Wolof. Verlag LINCOM, Munich, Germany 2003, ISBN 3-89586-616-4.

- Sana Camara: Wolof Lexicon and Grammar, NALRC Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-59703-012-0.

- Dictionary

- Diouf, Jean-Leopold:Dictionaire wolof-français et français-wolof,Karthala,2003

- Mamadou Cissé: Dictionnaire Français-Wolof, L’Asiathèque, Paris, 1998, ISBN 2-911053-43-5

- Arame Fal, Rosine Santos, Jean Léonce Doneux: Dictionnaire wolof-français (suivi d'un index français-wolof). Karthala, Paris, France 1990, ISBN 2-86537-233-2.

- Pamela Munro, Dieynaba Gaye: Ay Baati Wolof - A Wolof Dictionary. UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, No. 19, Los Angeles, California, 1997.

- Peace Corps The Gambia: Wollof-English Dictionary, PO Box 582, Banjul, The Gambia, 1995 (no ISBN, available as PDF file via the internet; this book refers solely to the dialect spoken in the Gambia and does not use the standard orthography of CLAD).

- Nyima Kantorek: Wolof Dictionary & Phrasebook, Hippocrene Books, 2005, ISBN 0-7818-1086-8 (this book refers predominantly to the dialect spoken in the Gambia and does not use the standard orthography of CLAD).

- Sana Camara: Wolof Lexicon and Grammar, NALRC Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-59703-012-0.

- Official documents

- Government of Senegal, Décret n° 71-566 du 21 mai 1971 relatif à la transcription des langues nationales, modifié par décret n° 72-702 du 16 juin 1972.

- Government of Senegal, Décrets n° 75-1026 du 10 octobre 1975 et n° 85-1232 du 20 novembre 1985 relatifs à l'orthographe et à la séparation des mots en wolof.

- Government of Senegal, Décret n° 2005-992 du 21 octobre 2005 relatif à l'orthographe et à la séparation des mots en wolof.

External links

- Wolof Language Resources

- Ethnologue Site on the Wolof Language

- An Annotated Guide to Learning the Wolof Language

- Yahoo group about Wolof (in English and German)

- Wolof Online

- Wolof English Dictionary (this dictionary mixes Senagalese and Gambian variants without notice, and does not use a standard orthography)

- A French-Wolof-French dictionary partially available at Google Books.

- Firicat.com (an online Wolof to English translator; you can add your own words to this dictionary; refers almost exclusively to the Gambian variants and does not use a standard orthography)

- PanAfrican L10n page on Wolof

- OSAD spécialisée dans l’éducation non formelle et l’édition des ouvrages en langues nationales

- JangaWolof.wordpress.com (A blog about the Wolof language and culture)

- xLingua - Online-Dictionary German-Wolof/Wolof-German, 2009

Languages of the African Union Working Transnational National Categories:- Senegambian languages

- Languages of the Gambia

- Languages of Senegal

- Languages of Mauritania

- Atlantic–Congo

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.