- Richard Hooker

-

This article is about the Anglican theologian. For the author, see Richard Hooker (author).

Richard Hooker

Born March 1554

Heavitree, Exeter, DevonDied 3 November 1600

Bishopsbourne, KentEducation Corpus Christi College, Oxford Spouse Jean Churchman Church Church of England Ordained 14 August 1579 Offices held Subdean, Rector Richard Hooker (March 1554 – 3 November 1600) was an Anglican priest and an influential theologian.[1] Hooker's emphases on reason, tolerance and the value of tradition came to exert a lasting influence on the development of the Church of England. In retrospect he has been taken (with Thomas Cranmer and Matthew Parker) as a founder of Anglicanism in its theological thought.

Contents

Youth (1554-1581)

Details of Hooker's life come chiefly from Izaak Walton’s biography of him. Hooker was born in the village of Heavitree in Exeter, Devon sometime around Easter Sunday.[2] He attended Exeter Grammar School until 1569. Richard came from a good family, but one that was neither noble nor wealthy. His uncle John Hooker was a success and served as the chamberlain of Exeter.

Hooker's uncle was able to obtain for Richard the help of another Devon native, John Jewel, bishop of Salisbury. The bishop saw to it that Richard was accepted to Corpus Christi College, Oxford, where he became a fellow of the society in 1577.[2] On 14 August 1579 Hooker was ordained a priest by Edwin Sandys, then bishop of London. Sandys made Hooker tutor his son Edwin, and Richard also taught George Cranmer, the great nephew of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

Marriage (1581-1584)

In 1581, Hooker was appointed to preach at Paul’s Cross. It was at this time, according to his biographer Walton, that Hooker made the "fatal mistake" of marrying his landlady’s daughter, Jean Churchman. As Walton put it:[citation needed]

“There is a wheel within a wheel; a secret sacred wheel of Providence (most visible in marriages), guided by His hand that allows not the race to the swift nor bread to the wise, nor good wives to good men: and He that can bring good out of evil (for mortals are blind to this reason) only knows why this blessing was denied to patient Job, to meek Moses, and to our as meek and patient Mr Hooker.”

In truth, the Churchman family belonged to the puritan wing of the Church of England and they must have been extremely obnoxious to the high church associates of Hooker. Nevertheless, he seems to have been a good husband who treated his wife with respect. The couple would have six children together, only two of whom survived beyond the age of 21. Hooker named Jean executrix in his will.[citation needed]

Later years (1584-1600)

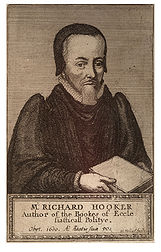

Portrait of Hooker

Portrait of Hooker

Hooker became rector of St. Mary's Drayton Beauchamp in Buckinghamshire in 1584.[2] The following year, Archbishop Edwin Sandys brought Hooker to the attention of Queen Elizabeth I, who appointed him Master (i.e. rector) of the Temple Church in London. There, Hooker soon came into public conflict with Walter Travers, a leading Puritan and Assistant at the Temple.[1]

Hooker later served as Subdean of Salisbury Cathedral and Rector of St. Andrew's Boscomb in Wiltshire.[2] The influential character of Hooker's writings, particularly Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, cannot be overestimated. Published in 1593, and subsequently, Hooker's eight volume work is primarily a treatise on Church-state relations, but it also deals comprehensively with issues of biblical interpretation, soteriology, ethics, and sanctification. Throughout the work, Hooker makes clear that theology involves prayer and is concerned with ultimate issues, and that theology is relevant to the social mission of the church.

In 1595, Hooker became Rector of the parishes of St. Mary the Virgin in Bishopsbourne and St. John the Baptist Barham in Kent. He died 3 November 1600 at his Rectory Bishopsbourne.[2] He was buried in the chancel of Bishopsbourne church, and subsequently a monument to him was erected there by William Cowper in 1632. In Hooker's Will it states: "Item, I give and bequeth three pounds of lawful English money towards the building and making of a newer and sufficient pulpitt in the p'sh of Bishopsbourne." The pulpit can still be seen in Bishopsbourne church, along with a statue of him, and currently an exhibition about his contribution to the Church of England.

Works

Learned Discourse of Justification

The statue of Richard Hooker in front of Exeter Cathedral.

The statue of Richard Hooker in front of Exeter Cathedral.

An important work was Hooker's sermon of 1585, A Learned Discourse of Justification, Works, and how the Foundation of Faith is Overthrown. In this he defended his belief in the doctrine of Justification by faith, but argued that even those who did not understand or accept this could be saved by God. This therefore included Roman Catholics, and emphasised Hooker's belief that Christians should concentrate more on what united them, rather than on what divided them. Hooker thus further articulated the Reformed nature of the English Church alongside its claim of belonging to the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church founded by Christ and the Apostles. Sermons much like this one provoked a reaction that led to his greatest work. Walter Travers, for example, publicly attacked Hooker's extension of salvation to Roman Catholics and elsewhere critics complained that his support of reforms in the church did not go far enough. Hooker responded with his masterpiece, Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie.

Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie

Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie is Hooker's best-known work, with the first four books being published in 1594. The fifth was published in 1597, while the final three were published posthumously,[1] and indeed may not all be his own work. Hooker argued for a middle way or via media between the positions in his time of the Roman Catholics and the Puritans. In these books, it was argued that reason and tradition were important when interpreting the Scriptures, and that it was important to recognise that the Bible was written in a particular historical context, in response to specific situations: "Words must be taken according to the matter whereof they are uttered.".[3]

It is a massive work, with its principal subject is the proper governance of the churches ("polity"). The Puritans, then known in England as the "Geneva Church" for John Calvin's influence on them, advocated the demotion of clergy and ecclesiasticism. Hooker attempted to work out which methods of organizing churches are best.[1] What was at stake behind the theology was the position of the Queen Elizabeth I as the Supreme Governor of the Church. If doctrine were not to be settled by authorities, and if Martin Luther's argument for the priesthood of all believers were to be followed to its extreme with government by the Elect, then having the monarch as the governor of the church was intolerable. On the other side, if the monarch were appointed by God to be the governor of the church, then local parishes going their own ways on doctrine were similarly intolerable.

The Laws is remembered not only for its stature as a monumental work of Anglican thought, but also for its influence in the development of theology, political theory, and English prose (being one of the first major works of theology written in English).

Scholastic thought in a latitudinarian manner

Hooker worked from Thomas Aquinas, but he adapted scholastic thought in a latitudinarian manner. He argued that church organization, like political organization, is one of the "things indifferent" to God. He wrote that minor doctrinal issues were not issues that damned or saved the soul, but rather frameworks surrounding the moral and religious life of the believer. He argued there were good monarchies and bad ones, good democracies and bad ones, and good church hierarchies and bad ones: what mattered was the piety of the people. At the same time, Hooker argued that authority was commanded by the Bible and by the traditions of the early church, but authority was something that had to be based on piety and reason rather than automatic investiture. This was because authority had to be obeyed even if it were wrong and needed to be remedied by right reason and the Holy Spirit. Notably, Hooker's affirmed that the power and propriety of bishops need not be in every case absolute.

Legacy

King James I is quoted by Izaak Walton, Hooker's biographer, as saying, "I observe there is in Mr. Hooker no affected language; but a grave, comprehensive, clear manifestation of reason, and that backed with the authority of the Scriptures, the fathers and schoolmen, and with all law both sacred and civil." [4] Hooker's emphasis on Scripture, reason, and tradition considerably influenced the development of Anglicanism, as well as many political philosophers, including John Locke.[1] Locke quotes Hooker numerous times in The Second Treatise of Civil Government. In the Church of England he is celebrated with a Lesser Festival on 3 November; the same day is also a Lesser Feast in his honor in the Episcopal calendar of saints.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church by F. L. Cross (Editor), E. A. Livingstone (Editor) Oxford University Press, USA; 3 edition p.789 (March 13, 1997)

- ^ a b c d e Philip B., Secor. "Richard Hooker Prophet of Anglicanism". Exeter Cathedral. Exeter Cathedral. http://www.exeter-cathedral.org.uk/Clergy/Hooker.html. Retrieved August 2007.

- ^ Hooker, Richard, Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie (1593 - 1662) Book IV.11.7

- ^ *Walton, Izaac, The Life of Mr Rich. Hooker. In Walton's Lives. Edited by George Saintsbury and reprinted in Oxford World's Classics, 1927.

Further reading

- Brydon, Michael, The Evolving Reputation of Richard Hooker: An Examination of Responses, 1600–1714 (Oxford, 2006).

- Faulkner, Robert K., Richard Hooker and the Politics of a Christian England (1981)

- Grislis, Egil, Richard Hooker: A Selected Bibliography (1971)

- Hooker, Richard, A Learned Discourse of Justification. 1612.

- Hooker, Richard, Works (Three volumes). Edited by John Keble, Oxford, 1836; Revised by R. W. Church and F. Paget, Oxford, 1888. Reprint by Burt Franklin, 1970 and by Via Media Publications.

- Kirby, W.J.T. (1998). "Richard Hooker's Discourse On Natural Law in the Context of the Magisterial Reformation". Animus 3. ISSN 1209-0689. http://www2.swgc.mun.ca/animus/Articles/Volume%203/kirby3.pdf. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- A. C. McGrade, ed., Richard Hooker and the Construction of Christian community (1997)

- Munz, Peter, The Place of Hooker in the History of Thought (1952, repr. 1971).

External links

- Hooker's works online

- Hooker's works online

- Entry on Hooker in Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- Biographical sketch

- Archbishop Rowan Williams' lecture on The Laws

- Exeter cathedral page

- Hooker at the Temple Church

- Hooker at Bishopsbourne Church including summary of his dates and writings

- Richard Hooker in Dictionary of British Philosophers

- This article incorporates text from the public domain 1907 edition of The Nuttall Encyclopædia.

Anglican Communion Organisation

Background Æthelberht of Kent · Edwin of Northumbria · Offa of Mercia · Christianity · Christian Church · Anglicanism · History · Jesus · Christ · Saint Paul · Catholicity and Catholicism · Apostolic Succession · Ministry · Ecumenical councils · Augustine of Canterbury · Paulinus of York · Hygeberht · Bede · Medieval Architecture · Henry VIII · Reformation · Thomas Cranmer · Dissolution of the Monasteries · Church of England · Edward VI · Elizabeth I · Matthew Parker · Richard Hooker · James I · Authorized Version · Charles I · William Laud · Nonjuring schism · Ordination of women · Homosexuality · Windsor Report

Theology Liturgy and worship Book of Common Prayer · Morning / Evening Prayer · Eucharist · Liturgical year · Biblical canon · Books of Homilies · High Church · Low Church · Broad Church

Other topics Ecumenism · Monasticism · Sermons · Prayer · Anglican rosary · Music · Liturgy · Symbols · Art

Anglicanism portal

Categories:- English Reformation

- Anglicanism

- English Christian theologians

- English Anglican priests

- Clergy of the Tudor period

- People from Exeter

- 1554 births

- 1600 deaths

- Burials in England

- Anglican theologians

- Anglican saints

- 16th-century English people

- 17th-century English people

- People of the Tudor period

- 16th-century theologians

- 17th-century theologians

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.