- Gastornis

-

Gastornis

Temporal range: 56–40 Ma

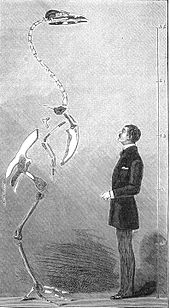

Mounted skeleton of G. giganteus Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: †Gastornithidae Genus: †Gastornis

Hébert, 1855[1]Type species †Gastornis parisiensis

Hébert, 1855Species Synonyms - Barornis Marsh, 1894

- Diatryma Cope, 1876

- Omorhamphus Sinclair, 1928

and see text

Gastornis is an extinct genus of large flightless bird that lived during the late Paleocene and Eocene epochs of the Cenozoic. It was named in 1855, after Gaston Planté, who had discovered the first fossils in Argile Plastique formation deposits at Meudon near Paris (France).[2] At that time, Planté (described as a "studious young man full of zeal"[2]) was at the start of his academic career, and his remarkable discovery was soon to be overshadowed by his subsequent achievements in physics.

In the 1870s, the famous American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope discovered another, more complete set of fossils in North America, and named them Diatryma (

/ˌdaɪ.əˈtraɪmə/ dy-ə-try-mə,[3] from Ancient Greek διάτρημα, diatrema, meaning "canoe"[4][5]).

/ˌdaɪ.əˈtraɪmə/ dy-ə-try-mə,[3] from Ancient Greek διάτρημα, diatrema, meaning "canoe"[4][5]).The fossil remains of these birds have been found in western-central Europe (England, Belgium, France and Germany).

Contents

Description

Gastornis parisiensis measured on average 1.75 metres (5.7 ft) tall, but large individuals grew up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) tall. The Gastornis had a remarkably huge beak with a slightly hooked top, which was taken as evidence suggesting that it was carnivorous. Gastornis had large powerful legs, with large, taloned feet, which also were considered in support of the theory that it was a predator.

The plumage of Gastornis is unknown; it is generally depicted with a hair-like covering as in ratites, but this is conjectural. Some fibrous strands recovered from a Green River Formation deposit at Roan Creek, Colorado were initially believed to represent Gastornis feathers and named Diatryma filifera.[6] Subsequent examination showed that they were actually not feathers at all but plant fibers or similar.[7]

Taxonomy and systematics

The skull of Gastornis remained unknown except for nondescript fragments, and several bones assigned to it were those of other animals. Thus, the European bird was long reconstructed as a sort of gigantic crane-like ornithuran, very different from the North American species.[8] Eventually this was sorted out, and only then it was realized that Gastornis and Diatryma were so much alike to make many scientists today consider the latter a junior synonym of the former pending a comprehensive review. Consequently the correct scientific name is Gastornis. In fact, this similarity was recognized as early as 1884 by Elliott Coues, but his reasoning was initially discounted and subsequently ignored until the late 20th century.[9]

Gastornis were variously considered allied with diverse birds, such as waterfowl, ratites or waders. Their highly apomorphic anatomy makes reliable assignment to any one group of birds difficult, in particular since no particularly close relatives survive today. In modern times, they were placed with the "Gruiformes" assemblage, which includes cranes. But in the 21st century, these birds are most often considered to be Galloanseres, or "fowls", in the same superorder as chickens and waterfowl. Quite ironically, the original assessment of Hébert - who perceived similarities with the Anseriformes in the original tibia - thus would be far more correct than any later placement. Incidentally, since the Galloanseres are known to originate in the Cretaceous already, it is comfortably explained how such a gigantic bird could be around less than 10 million years after the non-avian dinosaurs became extinct.

The following species are accepted today:

- Gastornis parisiensis Hébert, 1855 - the type species

- Late Paleocene - Early Eocene of WC Europe

- Synonyms: Gastornis edwardsii Lemoine, 1878; G. klaasseni Newton, 1885; G. pariensis (lapsus)

- Gastornis russeli L.Martin, 1992

- Late Paleocene of Berru, France

- Gastornis sarasini (Schaub, 1929)

- Early Eocene - middle Eocene of WC Europe

- Gastornis giganteus Cope, 1876

- Early -? middle Eocene of SC North America

- Synonyms: Barornis regens Marsh, 1894; Omorhamphus storchii Sinclair, 1928; O. storchi Wetmore, 1931 (unjustified emendation) Omorhamphus storchii was described based on fossils from the Lower Eocene of Wyoming.[10] The species was named in honor of T. C. von Storch, who found the fossils remains in Princeton 1927 Expedition.[11].

Paleoecology

At its time, the environment in which Gastornis lived had large portions of dense forest and a moist semiarid, subtropical or tropical climate. North America and Europe were still rather close, and especially since Greenland was probably then covered with lush woodland and grassland, only narrow straits of a few 100 km would have blocked entirely landbound dispersal of the Gastornis ancestors. While there were large contiguous areas of land in their North American range after the Western Interior Seaway had receded, their European range was an archipelago due to the Alpide orogeny and the high sea levels of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum; geographically (but not geologically), it was perhaps roughly similar to today's Indonesia.

Classically, Gastornis has been depicted as predatory. However, with the size of Gastornis legs, the bird would have had to have been more agile to catch fast-moving prey than the fossils suggest it to have been. Consequently, it has been suspected that Gastornis was an ambush hunter and/or used pack hunting techniques to pursue or ambush prey; if Gastornis was a predator, it would have certainly needed some other means of hunting prey through the dense forest[citation needed].

Alternatively, they may have been predominantly scavengers, omnivores or even herbivores. Indeed, the large beak of Gastornis would have been as well suited for crushing seeds and tearing off vegetation. But it seems excessively strong for a purely vegetarian diet, except in the rather improbable case that huge hard-shelled seeds and nuts formed the main food item of Gastornis. Regardless of what these birds ate, the beak may simply have been used for social display though its presence in all known fossils argues against a sexual display role. These contradicting hypotheses, equivocally supported by the material evidence, make the dietary paleobiology of Gastornis impossible to pinpoint.

Similar gigantic birds of the Cenozoic were the South American terror birds (phorusrhacids) and the Australian mihirungs (Dromornithidae). The former were certainly carnivorous, and the latter are suspected of being predators, too. On the other hand, ratites, the flightless giant birds of our time, feed on plants, small vertebrates, and invertebrates. Gastornis were among the largest, if not the largest birds alive during the Paleogene. They had few natural enemies and serious competitors apart from other Gastornis or then-rare large mammals, such as the predatory bear-like Arctocyon of Europe. If these huge birds were active hunters, they must have been important apex predators that dominated the forest ecosystems of North America and Europe until the middle Eocene. The mid-Eocene saw the rise of large creodont and mesonychid predators to ecological prominence in Eurasia and North America; the appearance of these new predators coincides with the decline of Gastornis and its relatives. This was possibly due to an increased tendency of mammalian predators to hunt together in packs (prevalent especially in hyaenodont creodonts). The fact that no birds appear to have ever weighed much more than half a metric ton suggests that they were restricted in their ability to evolve to larger and larger sizes, and thus in their ability to out-evolve apex predators by sheer bulk as mammals are often able to do (see Cope's Rule).

The fossil bones originally described as Omorhamphus storchii are the remains of a juvenile Gastornis giganteus.[12] Specimen YPM PU 13258 from Early Eocene Willwood Formation rocks of Park County, Wyoming[13] also seems to be a juvenile - perhaps of G. giganteus too, in which case it would be an even younger individual.[14]

Trace fossils

G. giganteus skeleton mounted as if walking, National Museum of Natural History

G. giganteus skeleton mounted as if walking, National Museum of Natural History

In Late Paleocene deposits of Spain and Early Eocene deposits of France, shell fragments of huge eggs have turned up, namely in the Provence.[15] These were described as the ichnotaxon Ornitholithus[16] and are presumably from Gastornis. While no direct association exists between Ornitholithus and Gastornis fossils, no other birds of sufficient size are known from that time and place: while the large Diogenornis and Eremopezus are known from the Eocene, the former lived in South America (still separated from North America by the Tethys Ocean then) and the latter is only known from the Late Eocene of North Africa, which also was separated by an (albeit less wide) stretch of the Tethys Ocean from Europe.[17] The mid-Eocene ostrich relative Palaeotis from Europe, on the other hand, was a bustard-sized bird, and the mysterious large Remiornis from France is only known from Paleocene remains.

Some of these fragments were complete enough to reconstruct a size of 24 by 10 cm (about 9.5 by 4 inches) with shells 2.3-2.5 mm (0.09-0.1 in) thick,[15] roughly half again as large as an ostrich egg and very different in shape from the more rounded ratite eggs. If Remiornis is indeed correctly identified as a ratite (which is quite doubtful however[9]), Gastornis remains as the only known animal that could have laid these eggs. It is also notable that at least one species of Remiornis is known to have been smaller than the Gastornis, and was initially described as Gastornis minor by Mlíkovský in 2002. This would nicely match the remains of eggs a bit smaller than those of the living Ostrich which have also been found in Paleogene deposits of Provence, were it not for the fact that these eggshell fossils also date from the Eocene but no Remiornis bones are known from that time yet.[18]

There is no footprint record which is unequivocally known to be of Gastornis. This may be somewhat surprising, as there is an abundant record of fossilized bird and non-avian dinosaur tracks from the Cretaceous and Paleogene. But most of these are from shorelines or swamps, and thus the lack of Gastornis footprints might indicate that these birds stayed off soft ground, preferring terrain where they had better footing and consequently did not leave many trackways.

However, two mysterious footprint fossilizations are known that might be of Gastornis. One set of footprints was reported from Late Eocene gypsum at Montmorency and other locations of the Paris Basin in the 19th century, from 1859 onwards. Described initially by Jules Desnoyers and later on by Alphonse Milne-Edwards, these ichnofossils were quite celebrated, and most French geologists of the late 19th century knew about them. They were discussed by Charles Lyell in his Elements of Geology as an example of the incompleteness of the fossil record - no bones had been found associated with the footprints.[19] Unfortunately, these fine specimens which sometimes preserved even details of the skin structure are now lost. They were brought to the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle when Desnoyers started to work there, and the last documented record of them deals with their presence in the geology exhibition of the MNHN in 1912. The largest of these footprints, although only consisting of a single toe's impression, was a stunning 40 cm (16 in) long. Interestingly, the large footprints from the Paris Basin could also be divided into huge and "merely" large examples, much like the eggshells from southern France which are 20 million years older.[17]

The other footprint record consists of a single imprint which still exists, though it has proven to be even more controversial. It was found in Late Eocene Puget Group rocks in the Green River valley near Black Diamond, Washington. After its discovery, it raised considerable interest in the Seattle area in May–July 1992, being subject of at least two longer articles in the Seattle Times.[20] Variously declared a hoax or genuine, this apparent impression of a single bird foot measures about 27 cm wide by 32 cm long (11 by 13 in) and lacks a hallux (hind toe); it was described as the ichnotaxon Ornithoformipes controversus. 14 years after the initial discovery, the debate about the find's authenticity was still unresolved.[21] The specimen is now at Western Washington University.[22][23]

The problem with these trace fossils is that no fossil of Gastornis has been found to be younger than about 45 million years. The enigmatic "Diatryma" cotei is known from remains almost as old as the Paris basin footprints (whose date never could be accurately determined), but in North America the fossil record of unequivocal gastornithids seems to end even earlier than in Europe.[24]

Footnotes

- ^ Fide Prévost (1855)

- ^ a b Prévost (1855)

- ^ The biologist's handbook of pronunciations (1960)

- ^ Cope (1976)

- ^ LSJ, s.v.

- ^ Cockerell (1923)

- ^ Wetmore (1930)

- ^ Lemoine (1881a,b)

- ^ a b Mlíkovský (2002)

- ^ Sinclair, W. J. 1928. Omorhamphus, a New Flightless Bird from the Lower Eocene of Wyoming. Proc. Amer. Philosophical Society LXVII (1): 51-65.

- ^ The Auk. Recent Literature. XLV 1928

- ^ Brodkorb (1967): p.144

- ^ "Parly" in Wetmore (1933) is a misprint.

- ^ Wetmore (1933)

- ^ a b Dughi & Sirugue (1959), Fabre-Taxy & Touraine (1960)

- ^ Not Ornitholithes, contra Mlíkovský (2002) - that is an obsolete term for bird fossils in general (see e.g. Cuvier 1800).

- ^ a b Buffetaut (2004)

- ^ Fabre-Taxy & Touraine (1960)

- ^ Lyell (1865): pp.298-300

- ^ Dietrich (1992a,b)

- ^ Doughton (2004), Bigelow (2006)

- ^ Bigelow (2006)

- ^ Patterson & Lockley (2004)

- ^ Buffetaut (2004), Patterson & Lockley (2004)

References

- Bigelow, Phil (2006): Controversial Patterson "Diatryma footprint" slab has been moved. Posted on the Dinosaur Mailing List 2006-APR-02. HTML fulltext

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1967): Catalogue of Fossil Birds: Part 3 (Ralliformes, Ichthyornithiformes, Charadriiformes). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 11(3). PDF or JPEG fulltext

- Buffetaut, Eric (2004): Footprints of Giant Birds from the Upper Eocene of the Paris Basin: An Ichnological Enigma. Ichnos 11(3-4): 357-362. doi:10.1080/10420940490442287 (HTML abstract)

- Cockerell, Theodore Dru Alison (1923): The Supposed Plumage of the Eocene Bird Diatryma. American Museum Novitates 62: 1-4. PDF fulltext

- Cope, Edward Drinker (1876): On a gigantic bird from the Eocene of New Mexico. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 28(2): 10-11.

- Cox, Barry; Harrison, Colin; Savage, R.J.G. & Gardiner, Brian (1999): The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. Simon & Schuster.

- Cuvier, Georges (1800): Sur les Ornitholithes de Montmartre ["On the bird fossils of Montmartre"]. Bulletin des Sciences par la société Philomatique de Paris 41: 129. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Dietrich, B. (1992a): 'Big Bird' Footprint Has Scientists Aflutter - If Proven, Fossil Find Would Be A State First. Seattle Times, 1992-MYA-03: B1–2. HTML fulltext

- Dietrich, B. (1992b): Track Is Hoax, Paleontologists Say - Expert On Prehistoric Bird Casts Doubt On Discovery In State Park. Seattle Times, 1992-JUL-17: B4. HTML fulltext

- Doughton, Sandi (2004): Big birds on the Green River? The debate continues. Seattle Times, 2004-DEC-06. HTML fulltext

- Dughi, R. & Sirugue, F. (1959): Sur des fragments de coquilles d'oeufs fossiles de l'Eocène de Basse-Provence ["On fossil eggshell fragments from the Eocene of Basse-Provence"]. C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 249: 959-961 [Article in French]. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Fabre-Taxy, Suzanne & Touraine, Fernand (1960): Gisements d'œufs d'Oiseaux de très grande taille dans l'Eocène de Provence ["Deposits of eggs from birds of very large size from the Eocene of Provence"]. C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 250(23): 3870-3871 [Article in French]. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Haines, Tim & Chambers, Paul (2006) The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Firefly Books Ltd., Canada.

- Hébert, E. (1855a): Note sur le tibia du Gastornis pariensis [sic] ["Note on the tibia of G. parisiensis"]. C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 40: 579-582 [Article in French]. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Hébert, E. (1855b): Note sur le fémur du Gastornis parisiensis ["Note on the femur of G. parisiensis"]. C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 40: 1214-1217 [Article in French]. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Lartet, E. (1855): Note sur le tibia d'oiseau fossile de Meudon ["Note on the fossil bird tibia from Meudon"]. C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 40: 582-584 [Article in French]. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Lemoine, V. (1881a): Recherches sur les oiseaux fossiles des terrains tertiaires inférieurs des environs de Reims (Vol. 2): 75-170. Matot-Braine, Reims.

- Lemoine, V. (1881b): Sur le Gastornis Edwardsii et le Remiornis Heberti de l'éocène inférieur des environs de Reims ["On G. edwardsii and R. heberti from the Lower Eocene of the Reims area"]. C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 93: 1157-1159 [Article in French]. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Lyell, Charles (1865): Elements of Geology (6th ed.). J. Murray. HTML/PDF fulltext at Google Books.

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe. Ninox Press, Prague. ISBN 80-901105-3-8 PDF fulltext

- Norman, David (2001): The Big Book Of Dinosaurs. Welcome Books.

- Patterson, John & Lockley, Martin (2004): A Probable Diatryma Track from the Eocene of Washington: An Intriguing Case of Controversy and Skepticism. Ichnos 11(3-4): 341-347. doi:10.1080/10420940490442278

- Prévost, Constant (1855): Annonce de la découverte d'un oiseau fossile de taille gigantesque, trouvé à la partie inférieure de l'argile plastique des terrains parisiens ["Announcement of the discovery of a fossil bird of gigantic size, found in the lower Argile Plastique formation of the Paris region"]. C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 40: 554-557 [Article in French]. PDF fulltext at Gallica.

- Wetmore, Alexander (1930): The Supposed Plumage of the Eocene Diatryma. Auk 47(4): 579-580. DjVu fulltext PDF fulltext

- Wetmore, Alexander (1933): Fossil Bird Remains from the Eocene of Wyoming. Condor 35(3): 115-118. DjVu fulltext PDF fulltext

External links

- BBC Science and Nature

- "The unfinished story of the Early Tertiary giant bird Gastornis". Geological Society of Denmark. http://2dgf.dk/publikationer/dgf_on_line/vol_1/gastdk.htm. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

Categories:- Prehistoric birds of Europe

- Extinct flightless birds

- Gastornithiformes

- Genera of birds

- Eocene extinctions

- Prehistoric birds of North America

- Megafauna of North America

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.