- Moscow Metro

-

Moscow Metro

Info Locale Moscow

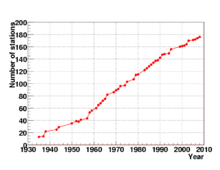

Krasnogorsk, Moscow OblastTransit type Metro Number of lines 12 Number of stations 182 Daily ridership 6.55 million (average, 2009), 8.95 million (highest in 2009) [1] Chief executive Ivan Besedin Website engl.mosmetro.ru Operation Began operation 15 May 1935 Operator(s) Moskovsky Metropoliten Technical Track gauge 1,520 mm (4 ft 11 5⁄6 in) Electrification 825 V DC third rail Average speed 41.55 kilometres per hour (25.82 mph) The Moscow Metro (Russian: Московский метрополитен, Moskovsky metropoliten) is a rapid transit system serving Moscow and the neighbouring town of Krasnogorsk. Opened in 1935 with one 11-kilometre (6.8 mi) line and 13 stations, it was the first underground railway system in the Soviet Union. As of 2011, the Moscow Metro has 182 stations and its route length is 301.2 kilometres (187.2 mi). The system is mostly underground, with the deepest section 84 metres (276 ft) below ground at the Park Pobedy station. The Moscow Metro is the world's second-most-heavily-used rapid transit system, after Tokyo's twin subway.[2]

Contents

Overview

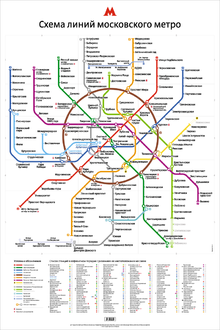

The Moscow Metro is a state-owned enterprise.[3] Its total length is 301.2 km (187.2 mi) and consists of 12 lines and 182 stations. The average daily passenger traffic is 6.6 million. Ridership is highest on weekdays (when the Metro carries over 7 million passengers per day) and lower on weekends. Each line is identified according to an alphanumeric index (usually consisting of a number), a name and a colour. Voice announcements refer to the lines by name. A male voice announces the next station when traveling towards the centre of the city, and a female voice when going away from it. On the circle line the clockwise direction has a male announcer for the stations, while the counter-clockwise direction has a female announcer. The lines are also assigned specific colours for maps and signs. Naming by colour is frequent in colloquial usage, except for the very similar shades of green assigned to the Kakhovskaya Line (route 11), the Zamoskvoretskaya Line (route 2), the Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya Line (route 10) and the Butovskaya Line (route L1).

The system operates in an enhanced spoke-hub distribution paradigm, with the majority of rail lines running radially from the centre of Moscow to the outlying areas. The Koltsevaya Line (route 5) forms a 20-kilometre (12 mi)long ring which enables passenger travel between these spokes. Signs showing the stations that can be reached in a given direction are in each station.[4] Most of the stations and lines are underground, but some lines have at-grade and elevated sections. The Filyovskaya Line is notable for being the only line with most of its route at grade.

The Moscow Metro is open from about 05:30 until 01:00. The precise opening time varies at different stations according to the arrival of the first train, but all stations close their entrances simultaneously at 01:00 for maintenance. The minimum interval between trains is 90 seconds, during the morning and evening rush hours.[1]

Lines

The colours in the table below correspond with the colours of the lines in the map above:

Index &

colourEnglish transliteration Russian name First opened Latest

extensionLength Stations

Sokolnicheskaya Сокольническая 1935 1990 26.1 km 19

Zamoskvoretskaya Замоскворецкая 1938 1985 36.9 km 20

Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Арбатско-Покровская 1938 2009 43.5 km 21

Filyovskaya Филёвская 19581 2006 14.9 km 13

Koltsevaya Кольцевая ("Circle") 1950 1954 19.3 km 12

Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya Калужско-Рижская 1958 1990 37.6 km 24

Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya Таганско-Краснопресненская 1966 1975 35.9 km 19

Kalininskaya Калининская 1979 1986 13.1 km 7

Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya Серпуховско-Тимирязевская 1983 2002 41.2 km 25

Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya Люблинско-Дмитровская 1995 2010 23.7 km 14

Kakhovskaya Каховская 19952 3.3 km 3  3

3Butovskaya Бутовская 2003 5.5 km 5 Total: 301 km 182 - Notes

A Moscow Metro train passes through Begovaya station. View from the driver's cabin

1 – Four central stations of the Filyovskaya Line – Alexandrovsky Sad (formerly Imeni Kominterna), Arbatskaya, Smolenskaya and Kiyevskaya – were originally opened in 1935–1937, when they were a branch of the Sokolnicheskaya Line. Between 1938 and 1953, they were part of the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line. The stations were closed between 1953 and 1958 and then reopened as part of the (new) Filyovskaya Line.

A branch line from the Filyovskaya is in operation (as of July 2009) starting from the Alexsandrovsky Sad Station and continuing on the Filyovskaya Line to Kiyevskaya Station, where it departs to stop at the (new) Vystavochnaya and Mezhdunarodnaya Stations.

2 – All three stations of the Kakhovskaya Line were built in 1969. They were an integral part of the Zamoskovoretskaya Line until 1983, becoming a branch of that line until 1995. In 1995, they were split off from the Zamoskovoretskaya Line to form the Kakhovskaya Line.

3 – The "L" in "L1" does not stand for "Light rail" but (somewhat confusingly) for "Light Metro"—lines which are mainly elevated, with shorter platforms. These lines, as a result, do not need expensive tunnelling and are supposed to be financially "light". However, "light" and "normal" metro lines use the same rolling stock. See Butovskaya Light Metro Line for further explanation.

The Moscow Monorail is a 4.7 km, six-station monorail line between Timiryazevskaya and VDNKh which opened in January 2008. Prior to the official opening, the monorail had operated in "excursion mode" since 2004. Trains departed every 20 minutes between 8:00 and 20:05, and tickets cost four times the normal price (50 rubles, ~$2.10). Since 2008, train intervals have been shortened and the price is equal to the Metro ticket price.

History

The first plans for a metro system in Moscow date back to the Russian Empire but were postponed by World War I, the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War. In 1923, the Moscow City Council formed the Underground Railway Design Office at the Moscow Board of Urban Railways. It carried out preliminary studies, and by 1928 had developed a project for the first route from Sokolniki to the city centre. At the same time, an offer was made to German company Siemens Bauunion to submit its own project for the same route. In June 1931, the decision to begin construction of the Moscow Metro was made by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In January 1932 the plan for the first lines was approved, and on March 21, 1933 the Soviet government approved a plan for 10 lines with a total route length of 80 km.

The first lines were built using the Moscow general plan designed by Lazar Kaganovich in the 1930s, and the Metro was named after him until 1955 named after him (Metropoliten im. L.M. Kaganovicha).[5] The Moscow Metro construction engineers consulted with their counterparts from the London Underground, the world's oldest metro system. Partly because of this connection, the design of Gants Hill tube station (although not completed until much later) is reminiscent of a Moscow Metro Station.[6][7]

First stage

The first line, from Okhotny Ryad to Smolenskaya, was opened to the public on 15 May 1935 at 07:00.[8] It was 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) long and included 13 stations. The line connected Sokolniki and Park Kultury.[9] The latter branch was extended westwards to a new station (Kiyevskaya) in March 1937, the first Metro line crossing the Moskva River over the Smolensky Metro Bridge.

Second stage

The second stage was completed before the war. In March 1938, the Arbatskaya branch was split and extended to the Kurskaya station (now the dark-blue Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line). In September 1938, the Gorkovskaya Line opened between Sokol and Teatralnaya. Here the architecture was based on that of the most popular stations in existence (Krasniye Vorota, Okhotnyi Ryad and Kropotkinskaya); while following the popular art-deco style, it was merged with socialist themes. The first deep-level Column station Mayakovskaya was built at the same time.

Third stage

Building work on the third stage was delayed (but not interrupted) during World War II, and two Metro sections were put into service; Teatralnaya–Avtozavodskaya (three stations, crossing the Moskva River through a deep tunnel) and Kurskaya–Partizanskaya (four stations) were inaugurated in 1943 and 1944 respectively. War motifs replaced socialist visions in the architectural design of these stations. During the Siege of Moscow in the fall and winter of 1941, Metro stations were used as air-raid shelters; the Council of Ministers moved its offices to the Mayakovskaya platforms, where Stalin made public speeches on several occasions. The Chistiye Prudy station was also walled off, and the headquarters of the Air Defence established there.

Fourth stage

After the war construction began on the fourth stage of the Metro, which included the Koltsevaya Line, a deep part of the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya line from Ploshchad Revolyutsii to Kievskaya and a surface extension to Pervomaiskaya during the early 1950s. The decoration and design characteristic of the Moscow Metro is considered to have reached its zenith in these stations. The Koltsevaya Line was first planned as a line running under the Garden Ring, a wide avenue encircling the borders of Moscow's city centre. The first part of the line – from Park Kultury to Kurskaya (1950) – follows this avenue. Plans were later changed and the northern part of the ring line runs 1–1.5 kilometres (0.62–0.93 mi) outside the Sadovoye Koltso, thus providing service for seven (out of nine) rail terminals. The next part of the Koltsevaya Line opened in 1952 (Kurskaya–Belorusskaya), and in 1954 the ring line was completed.

Cold War era

The beginning of the Cold War led to the construction of a deep section of the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line. The stations on this line were planned as shelters in the event of nuclear war. After finishing the line in 1953 the upper tracks between Ploshchad Revolyutsii and Kiyevskaya were closed, and later reopened in 1958 as a part of the Filyovskaya Line. In the further development of the Metro the term "stages" was not used any more, although sometimes the stations opened in 1957–1959 are referred to as the "fifth stage".

During the late 1950s the architectural extravagance of new Metro stations was toned down, and decorations at some stations (such as VDNKh and Alexeyevskaya) were simplified by comparison with the original plans. This was done on the orders of Nikita Khrushchev, who favoured more spartan decoration. A typical layout (which quickly became known as Sorokonozhka–"centipede", from early designs with 40 concrete columns in two rows) was developed for all new stations and the stations were built to look almost identical, differing from each other only in colours of the marble and ceramic tiles. Most stations were built with simpler, less-costly technology; this was not always appropriate, and resulted in utilitarian design. For example, walls with cheap ceramic tiles were susceptible to train vibration and some tiles eventually fell off. It was not always possible to replace the missing tiles with the ones of the same color, which eventually led to variegated parts of the walls. Not until the mid-1970s was the architectural extravagance restored and original designs again popular. However, the newer design of "centipede" stations (with 26 more-widely-spaced columns) continued to dominate.

Moscow Metro and Stalinism

Glorification

The Moscow Metro was one of the USSR’s most extravagant architectural projects. Stalin ordered the metro’s artists and architects to design a structure that embodied svet (radiance or brilliance) and svetloe budushchee (a radiant future).[10] With their reflective marble walls, high ceilings and grandiose chandeliers, many Moscow Metro stations have been likened to an “artificial underground sun”.[11] This underground communist paradise[12] reminded its riders that Stalin and his party had delivered something substantial to the people in return for their sacrifices. Most importantly, proletarian labor produced this svetloe budushchee.

Stalin developed a cult of personality through various methods of political and cultural propaganda. This propaganda effort was a concerted effort to encourage Soviet citizens to deify Stalin. Stalin referred to himself as "the god of the sun" because the sun is the source of all life, symbolizing a radiant future, eternal life and happiness. It was crucial that Stalin associate himself with the sun god, because the Communist Party’s power hinged on its promise to the people that the party could provide all that was symbolized by the sun.[citation needed]

The metro design’s emphasis on verticality was a reinforcement of Stalin's deification. He directed his architects to design structures which would encourage citizens to look up, admiring the station’s art (as if they were looking up to admire the sun and—by extension—him as a god.[13] Another aspect of the apotheosis propaganda was the metro’s electrification; the Moscow Metro's chandeliers are one of the most beautiful and technologically-advanced aspects of the project.

The chief lighting engineer was Abram Damsky, a graduate of the Higher State Art-Technical Institute in Moscow. By 1930 he was a chief designer in Moscow’s Elektrosvet Factory, and during World War II was sent to the Metrostroi (Metro Construction) Factory as head of the lighting shop.[14] Damsky recognized the importance of efficiency, as well as the potential for light as an expressive form. His team experimented with different materials (most often cast bronze, aluminum, sheet brass, steel, and milk glass) and methods to optimize the technology.[15] Damsky’s discourse on “Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950” describes in detail the epic chandeliers installed in the Kaluzhskaia (now called the Oktiabrskaia) Station and the Taganskaia Station:

The Kaluzhskaia Station was designed by the architect [Leonid] Poliakov. Poliakv’s decision to base his design on a reinterpretation of Russian classical architecture clearly influenced the concept of the lamps, some of which I planned in collaboration with the architect himself. The shape of the lamps was a torch – the torch of victory, as Poliakov put it... The artistic quality and stylistic unity of all the lamps throughout the station’s interior made them perhaps the most successful element of the architectural composition. All were made of cast aluminum decorated in a black and gold anodized coating, a technique which the Metrostroi factory had only just mastered. The Taganskaia Metro Station on the Ring Line was designed in...quite another style by the architects K.S. Ryzhkov and A. Medvedev... Their subject matter dealt with images of war and victory...The overall effect was one of ceremony, perhaps even lavish to excess. In the platform halls the blue ceramic bodies of the chandeliers played a more modest role, but still emphasised the overall expressiveness of the lamp.”[16]—Abram Damsky, Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950This is an example of how the artistic composition of the Moscow Metro incorporated the Communist Party’s propaganda messages. The work of Abram Damsky facilitated the dissemination of this propaganda, so the people would associate the party with svetloe budushchee.

Industrialisation

Stalin's First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932) facilitated rapid industrialisation to build a socialist motherland. The plan was ambitious, seeking to reorient an agrarian society towards industrialism. It was Stalin's fanatical energy, large-scale planning, and ambitious resource allocation that kept up industrialisation's punishing pace. The First Five-Year Plan was instrumental in the completion of the Moscow Metro; without industrialisation, the Soviet Union would not have had the raw materials necessary for the project. For example, steel was a main component of many subway stations. Before industrialisation, it would have been impossible for the Soviet Union to produce enough steel to incorporate it into the metro's design; in addition, a steel shortage would have limited the size of the subway system and its technological advancement.

The Moscow Metro furthered the construction of a socialist Soviet Union because the project accorded with Stalin's Second Five-Year Plan. The Second Plan focused on urbanisation and the development of social services. The Moscow Metro was necessary to cope with the influx of peasants who migrated to the city during the 1930s; Moscow's population grew to 3.6 million in 1933 from 2.16 million in 1928. The Metro also bolstered Moscow's shaky infrastructure and the its communal services, which hitherto were nearly nonexistent.[17]

Mobilisation

The Communist Party had the power to mobilise; because the party was a single source of control, it could focus its resources and inspire its people. The most notable example of mobilisation in the Soviet Union occurred during World War II. The country also mobilised in order to complete the Moscow Metro with unprecedented speed. A main motivation of the mobilization was to overtake the West and prove that a socialist metro could surpass capitalist designs. It was especially important to the Soviet Union that socialism succeed industrially, technologically, and artistically in the 1930s, since capitalism was at a low ebb during the Great Depression.

The person in charge of Metro mobilization was Lazar Kaganovich. A prominent Party member, he assumed control of the project as chief overseer. Kaganovich was nicknamed the "Iron Commissar"; he shared Stalin's fanatical energy, dramatic oratory flare, and ability to keep workers building quickly with threats and punishment.[18] He was determined to realise the Moscow Metro, regardless of cost. Without Kaganovich's managerial ability, the Moscow Metro might have met the same fate as the Palace of the Soviets: failure.

This was a comprehensive mobilisation; the project drew resources and workers from the entire Soviet Union. In his article, archeologist Mike O'Mahoney describes the scope of Metro mobilisation:

A specialist workforce had been drawn from many different regions, including miners from the Ukrainian and Siberian coalfields and construction workers from the iron and steel mills of Magnitogorsk, the Dniepr hydroelectric power station, and the Turkestan-Siberian railway... materials used in the construction of the metro included iron from Siberian Kuznetsk, timber from northern Russia, cement from the Volga region and the norther Caucasus, bitumen from Baku, and marble and granite from quarries in Karelia, the Crimea, the Caucasus, the Urals, and the Soviet Far East[19]—Mike O'Mahoney, Archeological Fantasies: Constructing History on the Moscow MetroSkilled engineers were scarce, and unskilled workers were instrumental to the realisation of the metro. The Metrostroi (the organisation responsible for the Metro's construction) conducted massive recruitment campaigns. It printed 15,000 copies of Udarnik metrostroia (Metrostroi Shock Worker, its daily newspaper) and 700 other newsletters (some in different languages) to attract unskilled laborers. Kaganovich was closely involved in the recruitment campaign, targeting the Komsomol generation because of its strength and youth.

Social engineering

The completion of the Moscow Metro was important, because the party used it as a means to build a socialist society. The Metro was perhaps the Soviet Union’s most effective social-engineering tool[20] not only due to the project’s scale, but also because Socialist Realism (the movement according to which the Metro was designed and built) was an instrument for such experimentation. Socialist Realism was in fact a method, not a style.[21] This method was influenced by Nikolay Chernyshevsky, Lenin’s favorite 19th-century nihilist, who stated that “art is no use unless it serves politics”.[22] This maxim explains why the stations combined aesthetics, technology and ideology. Any plan which did not incorporate all three areas cohesively were rejected. Without this cohesion, the Metro would not reflect Socialist Realism. If the Metro did not utilize Socialist Realism, it would fail to illustrate Stalinist values and transform Soviet citizens into socialists. Anything less than Socialist Realism’s grand artistic complexity would fail to inspire a long-lasting, nationalistic attachment to Stalin’s new society.[23]

Propaganda value

The first 13 stations of the Moscow Metro opened on May 15th, 1935, a day which was celebrated as a technological and ideological victory for socialism (and, by extension, Stalinism). 285,000 people rode the Metro at its debut, and its design was greeted with pride; street celebrations included parades, plays and concerts. The Bolshoi Theatre presented a choral performance by 2,200 Metro workers; 55,000 colored posters (lauding the Metro as the busiest and fastest in the world) and 25,000 copies of "Songs of the Joyous Metro Conquerors" were distributed.[24] This publicity barrage, produced by the Soviet government, stressed the superiority of the Moscow Metro over all other metros in capitalist societies and the Metro's role as a prototype for the Soviet future. In reality, the Moscow Metro averaged 16 miles per hour (26 km/h) and could not exceed 32 miles per hour (51 km/h). In comparison, New York City subway trains averaged 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) and had a top speed of 45 miles per hour (72 km/h).[25] While the celebration was an expression of popular joy it was also an effective propaganda display, legitimizing the Metro and declaring it a success.

Metro 2.1

It has been alleged that a second and deeper metro system code-named "D-6",[26] designed for emergency evacuation of key city personnel in case of nuclear attack during the Cold War, exists under military jurisdiction. It is believed that it consists of a single track connecting the Kremlin, chief HQ (General Staff–Genshtab), Lubyanka (FSB Headquarters), the Ministry of Defence and several other secret installations.[citation needed] There are alleged to be entrances to the system from several civilian buildings, such as the Russian State Library, Moscow State University (MSU) and at least two stations of the regular Metro. It is speculated that these would allow for the evacuation of a small number of randomly chosen civilians, in addition to most of the elite military personnel. A suspected junction between the secret system and the regular Metro is behind the Sportivnaya station on the Sokolnicheskaya Line. The final section of this system was completed in 1997.[27]

Specifications

The Moscow Metro uses the Russian gauge of 1,520 millimetres (60 in) (like other Russian railways) and an underrunning third rail with a supply of 825 V DC. The average distance between stations is 1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi); the shortest (502 metres (1,647 ft) long) section is between Vystavochnaya and Mezhdunarodnaya and the longest (6,627 metres (21,742 ft) long) is between Krylatskoye and Strogino. Long distances between stations have the positive effect of a high cruising speed of 41.7 kilometres per hour (25.9 mph). Since the beginning, platforms have been at least 155 metres (509 ft) long to accommodate eight-car trains. The only exceptions are on the Filyovskaya Line: Vystavochnaya, Mezhdunarodnaya, Studencheskaya, Kutuzovskaya, Fili, Bagrationovskaya, Filyovsky Park and Pionerskaya, which only allow six-car trains (note that this list includes all ground-level stations on the line, except Kuntsevskaya).

Trains on the Zamoskovretskaya, Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya, Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya, Kalininskaya, Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya and Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya lines have eight cars, on the Sokolnicheskaya line seven cars and on the Koltsevaya and Kakhovskaya lines six cars. The Filyovskaya and Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya lines had six- and seven-car trains as well, but now use four- and five-car articulated 81-740/741 trains. Rolling stock on the Koltsevaya line is being replaced with four-car Rusich trains. The Butovskaya Line light metro was designed by different standards, and has shorter (96-metre (315 ft)long) platforms. It employs articulated 81-740/741 trains, which consist of three cars (although the line can also use traditional four-car trains).

The Moscow Metro encompasses 182 stations, of which 73 are deep below ground and 88 shallower. Of the deep stations 52 are pylon-type, 18 are column-type and one is "single-vault" (Leningrad technology). The shallow stations comprise 63 pillar-type (a large portion of them following the "centipede" design), 20 single-vaults (Kharkov technology) and three single-decked. In addition, there are 11 ground-level stations and four above ground. Two of the stations exist as double halls, and two have three tracks. Five of the stations have side platforms (only one subterranean; that station Vorobyovy Gory is on a bridge). Three other metro bridges exist, but are covered or hidden. In addition, there are two closed stations and one that is in disrepair. Four stations are reserved for future service: Volokolamskaya on the Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya line, Delovoy Tsentr stations on the Kalininskaya and Solntsevskaya lines and Park Pobedy on the Solntsevskaya line.

Expansion plans

Current

The Moscow Metro has a set of expansion plans which are due to be achieved by 2015. Major projects include:

- Strogino-Mitino extension: The first stage of the extension opened in January 2008. The second stage extended the line 5.9 kilometres (3.7 mi) to Myakinino, Volokolamskaya and Mitino in December 2009; part of the track includes a new Metro bridge across the Moskva River. The final stage will add two more stations (Pyatnitskaya and Rozhdestveno) and a new depot. Another station, located between Krylatskoye and Strogino (Troitse-Lykovo), will be added.

- Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya Line: The long-delayed third stage of the line is being built (as of 2011). The first stage, including the Sretensky Bulvar and Trubnaya stations, was completed at the end of 2007. The second stage (3 km (1.9 mi) long, consisting of the Dostoyevskaya and Maryina Roshcha stations) opened on 19 June 2010. The third stage is the 8.0-kilometre (5.0 mi) Dmitrovsky Radius, which will open in 2013 with four stations: Sheremetyevskaya, Butyrsky Khutor, Petrovsko-Razumovskaya and Likhobory and a new depot. From there it is expected that another extension will follow after 2015, although its stations have not been confirmed: Seligerskaya, Yubileynaya, Degunino and Severnaya.

- Brateyevo-Zyablikovo extension: A project on the Zamoskvoretskaya and Lyublinskaya Lines. The former will extend by one station (2.9 kilometres (1.8 mi)) to Brateyevo with a new depot, and the latter by three (4.3 kilometres (2.7 mi)): Borisovo, Shipilovskaya and Zyablikovo, with a transfer point at Krasnogvardeyskaya-Zyablikovo. The new stations will ease congestion at the south end of the Zamoskvoretskaya Line. Construction began back in the late 1990s, but was suspended from 2001–2008; completion is expected in 2011.

- Zhulebino-Kosino extension: Originally reserved for light Metro lines, the success of the Butovskaya Line meant that in an attempt to relieve one of the busiest terminus stations of the Perovsky and Tagansky radii (Novogireyevo and Vykhino, respectively), both lines would extend by one station beyond the Moscow Ring Road: Kalininskaya Line to Novokosino in 2011 (3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi)) and Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya Line to Zhulebino in 2012 (3.4 kilometres (2.1 mi)). Both areas are within the city of Moscow, but lie outside the MKAD.

- Light Metro lines: Originally developed as a way of reducing costs by building an elevated Metro line to distant regions of Moscow, the only one of these (the Butovskaya Line) has been the subject of criticism. The fate of the L1 expansion remains questionable, while the Solntsevskaya Light Metro Line planned to begin construction in 2004 and open in 2006 with eight stations. In 2005 the project was altered; two stations were dropped, and the opening was delayed until 2010. In 2008 the line was cancelled in favour of the underground Solntsevskaya Metro Line (see below). The L1 extension (which has been revised and postponed) includes an underground extension 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) northwards to Bitsevsky Park (which will offer a transfer to the Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya Line) and a southwards three-station extension (also 5 km in length) including a new depot: Ulitsa Staropotapovskaya, Ulitsa Ostafyevskya and Novokuryanovo. All the listed light-metro work has been removed from Moscow Metro's expansion programme until 2015, and Moscow Metro may dismantle the system in favour of a conventional two- or three-station replacement on the Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya Line.[citation needed]

- Solntsevskaya Line: Following cancellation of the L2 the Moscow Metro revived an old project, bringing the Metro to the Solntsevo district outside Moscow. Initially foreseen as part of a major Solntsevo-Mytischinskaya chordial line, the current stretch suggests using the second set of tracks at Park Pobedy and having the line curve out along Michurin Avenue with four stations: Mosfilmovskaya, Lomonosovsky Prospekt, Michurinsky Prospekt and Olimpiyskaya Derevnya. This is planned for 2014, and would be the first stage of the line; the second stage would reach Solntsevo. In the original chordial project this included three stations, although the present plan still calls for the line to follow the Light Metro path. The project would also permit expansion of the line in the other direction, with a junction at the Delovoy Tsentr station in Moscow City. The fate of this project is unclear, since another project has replaced it.

- The Kalininskaya Line's western extension has the best chance of being realized. The line is planned to extend from Tretyakovskaya to Ostozhenka, Kadashevskaya and Smolenskaya (where it will unite nearby stations into one transfer unit) and continue westwards through the Moscow International Business Centre (where platforms have already been built) and along the Khoroshovo Highway. The project has not been finalized but it will eventually reach Strogino, where a second (parallel) station is under construction; an extension to Mitino is planned.

- Ghost stations: Moscow Metro does not have ghost stations in the conventional sense; of the three stations that were closed, two—Pervomayskaya (1954–61) and Kaluzhskaya (1964–74)—were temporary; one (Leninskiye Gory) was built on a bridge closed due to faulty construction; it was rebuilt and opened in 2002 as Vorobyovy Gory. Several planned stations were omitted; some were later completed, but some exist only on paper. The best-known was Volokolamskaya, which was built but never opened due to low ridership; it may open between 2015–2020, after the Tushino airfield is redeveloped. Other stations which may open are Maroseyka on the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line, which will offer a transfer to Kitay-gorod; Yakimanka on the Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya Line (transfer to Polyanka) and Suvorovskaya on the Koltsevaya Line, which was to be built with Dostoyevskaya but has since been postponed until the third stage of the LDL is complete. An exception is Tekhnopark, which will be built on the Zamoskvoretskaya Line's surface stretch in 2012 (the first station wholly sponsored by private investors).

According to plans by the Moscow city government and Russia's transport ministry (announced in September 2008), by 2015 79 kilometres (49 mi) of new lines, 43 new underground stations and 7 metro depots should be added to the system.

Recent developments

Since the turn of the 21st century several projects have been completed, and more are underway. The first was the Annino-Butovo extension, which extended the Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya Line from Prazhskaya to Ulitsa Akademika Yangelya in 2000, Annino in 2001 and Bulvar Dmitriya Donskogo in 2002. A new, elevated Butovskaya Light Metro Line was inaugurated in 2003. Another major project was the reconstruction of the Vorobyovy Gory station, which initially opened in 1959 and was forced to close in 1983 after the concrete used to build the bridge was found to be defective. After many years the station was rebuilt, and reopened in 2002.

Another recent project included building a branch off the Filyovskaya Line to the Moscow International Business Center. This included Delovoy Tsentr (opened in 2005) and Mezhdunarodnaya (opened in 2006). After many years of construction, the long-awaited Lyublinskaya Line extension was inaugurated with Trubnaya in August 2007 and Sretensky Bulvar in December of that year.

The Strogino-Mitino extension began with Park Pobedy in 2003. Its first stations (an expanded Kuntsevskaya and Strogino) opened in January 2008, and Slavyansky Bulvar followed in September. Myakinino, Volokolamskaya and Mitino opened in December 2009. Myakinino station was built by a state-private financial partnership, unique in Moscow Metro history.[28] In June 2010, the Lyublinskaya Line was extended with the Dostoyevskaya and Maryina Roscha stations.

New stations

-

Kuntsevskaya (2008)

-

Strogino (2008)

-

Slavyansky Bulvar (2008)

-

Myakinino (2009)

-

Mitino (2009)

-

Dostoyevskaya (2010)

-

Maryina Roshcha (2010)

Future proposals

Plans exist for the following projects:

- Chordial Lines: Projects for these appeared in the mid-1980s; they called for conventional radial lines but instead of passing through the city centre within the Koltsevaya Line, they would bypass them on the outside.[29] After four of these are completed, they will be used to form the new Second Ring service (see below). Construction began only on the Mitino-Butovskaya Line during the early 1980s. In the wake of the 1990s crises these projects were abandoned, replaced by more cost-effective means (including the Light Metro lines) and using existent segments. However (despite the Mitino-Butovo chord replacement), the Solntsevsky radius of the Solntsevo-Mytishchinskaya line has been regenerated in its original path. It is unknown whether it would cross all the northern radii before travelling to the adjacent city of Mytishchi along the Yaroslav Highway, since there is now a fast connection to Mytishchi via the Sputnik rail link from the Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal and a new plan to build a line from Delovoy Tsentr to Savyolovskaya would effectively duplicate the path. The fates of the Balashikha-Troparevskaya (southwest bypass) and the Khimsko-Lyuberetskaya (northeast bypass) chordial lines are unknown.

- Second (large) Ring: This well-known plan for a second ring line dates back to the 1960s.

- The original 1960s project called for a ring of 3–6 stations on the radius; several provisions for the future line were built (including transfer space at Bratislavskaya), the Kakhovskaya Line and the Cherkizovskaya–Ulitsa Podbelskogo section of the Sokolnicheskaya Line (allowing it to expand westwards into Izmaylovo).[30]

- During the 1980s chordial-line proposals the ring was to be formed out of the space enclosed by it, with a circular service operating at off-peak hours.[31]

- In 2006 Moscow Metro announced plans for a second transfer contour, which would build a line from Delovoy Tsentr to Savyolovskaya on a large diameter; this would in the future become enclosed into a ring, one to three stations along the radius.

However, this project is questionable and the second ring is as distant today as it looked 40 years ago.

Fares

Ticket rates effective January 2011 [32] Trip

limitCost Cost

per tripDiscount Valid for Fixed-rate Ultralight ticket 1 28.00 28.00 0% 5 days 2 56.00 28.00 0% 5 days 5 135.00 27.00 3.6% 45 days 10 265.00 26.50 5.4% 45 days 20 520.00 26.00 7.1% 45 days 60 1245.00 20.75 25.9% 45 days Monthly Ultralight ticket 70 1230.00 17.57 37.2% calendar month Transport Card unlimited, 7 min delay 1710.00 – 0% 30 days unlimited, 7 min delay 3485.00 – 32.0% 90 days unlimited, 7 min delay 11430.00 – 44.3% 365 days Transport Card

(for pupils and students)unlimited, 7 min delay 350.00 – 78.3% calendar month Social Card unlimited, no delay free – – infinite From the 1970s to the 1990s, the cost of a ride was five kopecks (1/20 of a Soviet ruble). The fare has been steadily rising since 1991, hastened by inflation (taking into account the 1998 revaluation of the ruble by a factor of 1000). Effective January 2011, one ride (or one item of oversize luggage) costs 28 rubles (94 US cents). Discounts (up to 40 percent) are available when buying a multiple-trip ticket (starting with five-trip cards), and children under age seven can travel free with their parents.

Tickets are available for a fixed number of trips, regardless of distance traveled or number of transfers. Monthly and yearly passes are also available. Fare enforcement takes place at the points of entry. Once a passenger has entered the Metro system, there are no further ticket checks – one can ride to any number of stations and make transfers within the system freely. Transfers to other public-transport systems (such as bus, tram, trolleybus, or monorail) are not covered by the ticket.

Before 1991, turnstiles accepted coins; however, with the start of hyperinflation plastic tokens of various design were used. Disposable magnetic stripe cards were introduced in 1993 on a trial basis, and used as unlimited monthly tickets between 1996 and 1998. The sale of tokens ended on 1 January 1999, and they stopped being accepted in February 1999; from that time, magnetic cards were used as tickets with a fixed number of trips.

On 1 September 1998, the Moscow Metro became the first metro system in Europe to fully implement plastic smart cards, known as Transport Cards. The card has an unlimited number of trips and may be programmed for 30, 90 or 365 days. The first purchase includes a one-time cost of 50 rubles, and its active lifetime is projected as 3½ years; defective cards are exchanged at no cost. Unlimited cards are also available for students at reduced price (as of 2011, 321 rubles—or about $US10—for a calendar month of unlimited usage) for a one-time cost of 70 rubles. Transport Cards impose a delay for each consecutive use; i.e. the card can not be used for seven minutes after the user has passed through the turnstile.

In January 2007, Moscow Metro began replacing magnetic cards with contactless disposable tickets based on NXP MIFARE ultralight technology. Ultralight tickets are available for a fixed number of trips in 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 60-trip denominations (valid for 5 or 45 days from the day of purchase) and as a monthly ticket, only valid for a selected calendar month and limited to 70 trips. The sale of magnetic cards stopped January 16, 2008 and magnetic cards stopped being accepted in late 2008, making the Moscow metro the world's first major public-transport system to run exclusively on a contact-less automatic fare-collection system.[33]

In August 2004, the city government launched the Muscovite's Social Card program. Social Cards are free smart cards issued for the elderly and other groups of citizens officially registered as residents of Moscow or the Moscow region; they offer discounts in shops and pharmacies, and double as credit cards issued by the Bank of Moscow. Social Cards can be used for unlimited free access to the city's public-transport system, including the Moscow Metro; while they do not feature the time delay, they include a photograph and are non-transferable.

Since 2006, several banks have issued credit cards which double as ultralight cards and are accepted at turnstiles. The fare is passed to the bank and the payment is withdrawn from the owner's bank account at the end of the calendar month, using a discount rate based on the number of trips that month (for up to 70 trips, the cost of each trip is prorated from current ultralight rates; each additional trip costs 24.14 rubles). [32] Partner banks include the Bank of Moscow, CitiBank, Rosbank, Alfa-Bank and Avangard Bank.[34] In fall 2010, Moscow Metro and Mobile TeleSystems launched a mobile ticketing service using near field communication-enabled SIM cards. [35]

Single-trip fares, 1935–2010

- 1935-05-15 — 50 kopecks

- 1935-08-01 — 40 kopecks (with season ticket — 35 kopecks)

- 1935-10-01 — 30 kopecks (with season ticket — 25 kopecks)

- 1942-05-31 — 40 kopecks

- 1948-08-16 — 50 kopecks*

- 1961-01-01 — 5 kopecks (revaluation)

- 1991-04-02 — 15 kopecks

- 1992-03-01 — 50 kopecks

- 1992-06-24 — 1 ruble

- 1992-12-01 — 3 rubles

- 1993-02-16 — 6 rubles

- 1993-06-25 — 10 rubles

- 1993-10-15 — 30 rubles

- 1994-01-01 — 50 rubles

- 1994-03-18 — 100 rubles

- 1994-06-23 — 150 rubles

- 1994-09-21 — 250 rubles

- 1994-12-20 — 400 rubles

- 1995-03-20 — 600 rubles

- 1995-07-21 — 800 rubles

- 1995-09-20 — 1000 rubles

- 1995-12-21 — 1500 rubles

- 1997-06-11 — 2000 rubles

- 1998-01-01 — 2 rubles (revaluation due to post-Soviet period inflation)

- 1998-09-01 — 3 rubles

- 1999-01-01 — 4 rubles

- 2000-07-15 — 5 rubles

- 2002-10-01 — 7 rubles

- 2004-04-01 — 10 rubles

- 2005-01-01 — 13 rubles

- 2006-01-01 — 15 rubles

- 2007-01-01 — 17 rubles

- 2008-01-01 — 19 rubles

- 2009-01-01 — 22 rubles

- 2010-01-01 — 26 rubles

- 2011-01-01 — 28 rubles

*Not taking into account 10X denomination of 1947. In fact, the fare increased 10 times.

Statistics

Passengers (2009) 2,392,200,000 passengers[36] — privileged category 912,600,000 passengers —— pupils and students 239,000,000 passengers Maximum daily ridership 8,952,000 passengers Revenue from fares (2005) 15.9974 billion rubles Total lines length 292.9 kilometres (182.0 mi) Number of lines 12 Longest line Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line (43.5 kilometres (27.0 mi)) Shortest line Kakhovskaya Line (3.3 kilometres (2.1 mi)) Longest section Strogino–Krylatskoye (6.7 kilometres (4.2 mi)) Shortest section Delovoy Tsentr–Mezhdunarodnaya (502 metres (1,647 ft)) Number of stations 182 — transfer stations 60 — transfer points 27 — surface/elevated 15 Deepest station Park Pobedy (84 metres (276 ft)) Most shallow underground station Pechatniki Station with the longest platform Vorobyovy Gory (Metro) (282 metres (925 ft)) Number of stations with a single entrance 70 Number of turnstiles with automatic control on entrances 2374 Number of stations with escalators 124 Number of escalators 631 — including Monorail stations 18 Total length of all escalators 65.4 kilometres (40.6 mi) Number of depots 15 Total number of train runs per day 9915 Average speed: — commercial 41.71 kilometres per hour (25.92 mph) — technical (2005) 48.85 kilometres per hour (30.35 mph) Total number of cars (average per day) 4428 Cars in service (average per day) 3397 Annual run of all cars 722,100,000 kilometres (448,700,000 mi) Average daily run of a car 556.2 kilometres (345.6 mi) Average passengers per car 53 people Longest escalator 126 metres (413 ft) (Park Pobedy) Total number of ventilation shafts 393 Number of local ventilation systems in use 4965 Number of medical assistance points (2005) 46 Total number of employees 34792 people — males 18291 people — females 16448 people Timetable fulfilment 99.96% Minimum average interval 90 sec Average passenger trip 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) Mishaps

1977 bombing

Main article: 1977 Moscow bombingsOn 8 January 1977, a bomb was reported to have killed 7 and seriously injured 33. It went off in a crowded train between Izmaylovskaya and Pervomayskaya stations.[37][38] Three Armenians were later arrested, charged and executed in connection with the incident.[39]

1981 station fires

In June 1981, seven bodies were seen being removed from the Oktyabrskaya station during a fire there. A fire was also reported at Prospekt Mira station about that time.[40]

1982 escalator accident

Main article: Aviamotornaya (Moscow Metro)A fatal accident occurred on 17 February 1982 due to an escalator collapse at the Aviamotornaya station on the Kalininskaya Line. 8 people were killed and 30 injured due to a pileup caused by faulty emergency brakes.[41]

2004 bombings

On 6 February 2004, an explosion wrecked a train between the Avtozavodskaya and Paveletskaya stations on the Zamoskvoretskaya Line, killing 39 and wounding over 100.[42] Chechen terrorists were blamed. A later investigation concluded that a Karachay-Cherkessian resident (an Islamic militant) had carried out a suicide bombing. The same group organized another attack on 31 August 2004.

2005 Moscow blackout

On 25 May 2005, a city-wide blackout halted operation on some lines. The following lines, however, continued operations: Sokolnicheskaya, Zamoskvoretskaya from Avtozavodskaya to Rechnoy Vokzal, Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya, Filyovskaya, Koltsevaya, Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya from Bitsevskiy Park to Oktyabrskaya-Radialnaya and from Prospekt Mira-Radialnaya to Medvedkovo, Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya, Kalininskaya, Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya from Serpukhovskaya to Altufyevo and Lyublinskaya from Chkalovskaya to Dubrovka.[43] There was no service on the Kakhovskaya and Butovskaya lines. The blackout severely affected the Zamoskvoretskaya and Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya lines, where initially all service was been disrupted because of trains halted in tunnels in the southern part of city (most affected by the blackout). Later, limited service resumed and passengers stranded in tunnels were evacuated. Some lines were only slightly impacted by the blackout, which mainly affected southern Moscow; the north, east and western parts of the city experienced little or no disruption.[43]

2006 billboard incident

On 19 March 2006 a construction pile from an unauthorized billboard installation was driven through a tunnel roof, hitting a train between the Sokol and Voikovskaya stations on the Zamoskvoretskaya Line. No injuries were reported.[44]

2010 bombing

Main article: 2010 Moscow Metro bombingsOn 29 March 2010, two bombs exploded on the Sokolnicheskaya Line. The first bomb went off at the Lubyanka station on the Sokolnicheskaya Line at 7:56, during the morning rush hour.[45] Reports suggested that 39 people were killed and 64 wounded. At least 24 were killed in the first explosion, of which 14 were in the rail car where the explosion took place. A second explosion occurred at the Park Kultury station at 8:38, roughly forty minutes after the first one.[45] Fourteen people were reported dead in that explosion. An increase in Russian islamophobia occurred following the bombings.[46][dead link]

See also

- List of Moscow metro stations

- Expansion timeline of the Moscow Metro

- List of metro systems

- Moscow Metro ridership statistics (Russian)

- Metro dogs

- Trams in Moscow

References

- ^ a b c "Метрополитен в цифрах" (in Russian). Moskovsky Metropoliten. http://mosmetro.ru/pages/page_0.php?id_page=99. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "Moscow Subway System Second Only to Tokyo in Usage". VOA. 2010-03-29. http://www1.voanews.com/english/news/europe/Moscow-Subway-System-Second-Only-to-Tokyo-in-Usage--89392252.html. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ Moscow Metro copyright notice

- ^ See this image as an example

- ^ Metro.ru Original order on naming the Metro after Kaganovich. Retrieved October 19, 2007

- ^ http://www.pootergeek.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/gants_hill.jpg

- ^ Lawrence, David (1994). Underground Architecture. Harrow: Capital Transport. ISBN 185414-160-0.

- ^ Sachak (date unknown). История создания Московского метро (History of Moscow Metro). Retrieved from http://sachak.chat.ru/istoria.html.

- ^ First Metro map. Retrieved from http://www.metro.ru/map/1935/metro.ru-1935map-big1.jpg.

- ^ Cooke, Catherine (1997). "Beauty as a Route to 'the Radiant Future': Responses of Soviet Architecture". Journal of Design History. Design, Stalin and the Thaw 10 (2): 137–160. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1316129. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Bowlt, John E. (2002). "Stalin as Isis and Ra: Socialist Realism and the Art of Design". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. Design, Culture, Identity: The Wolfsonian Collection 24: 34–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1504182.

- ^ Bowlt, John E. (2002). "Stalin as Isis and Ra: Socialist Realism and the Art of Design". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. Design, Culture, Identity: The Wolfsonian Collection 24: 34–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1504182.

- ^ Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilization". Technology and Culture 41 (4): 697–724. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2517594. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Damsky, Abram (Summer 1987). "Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 5 (Russian/Soviet Theme): 90–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1503938. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Damsky, Abram (Summer 1987). "Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 5 (Russian/Soviet Theme): 90–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1503938. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Damsky, Abram (Summer 1987). "Lamps and Architecture 1930–1950". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 5 (Russian/Soviet Theme): 90–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1503938. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilisation". Technology and Culture 41 (4): 697–724. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2517594. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilisation". Technology and Culture 41 (4): 697–724. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2517594. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ O'Mahoney, Mike (January 2003). "Archaeological Fantasies: Constructing History on the Moscow Metro". The Modern Language Review 98 (1): 138–150. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3738180. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilization". Technology and Culture 41 (4): 697–724. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2517594. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Cooke, Catherine (1997). "Beauty as a Route to 'the Radiant Future': Responses of Soviet Architecture". Journal of Design History. Design, Stalin and the Thaw 10 (2): 137–160. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1316129. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilization". Technology and Culture 41 (4): 697–724. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2517594. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Voyce, Arthur (January 1956). "Soviet Art and Architecture: Recent Developments". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Russia Since Stalin: Old Trends and New Problems 303: 104–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1032295. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilization". Technology and Culture 41 (4): 697–724. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2517594. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Jenks, Andrew (October 2000). "A Metro on the Mount: The Underground as a Church of Soviet Civilization". Technology and Culture 41 (4): 697–724. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2517594. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ "Moscow Metro 2 – The dark legend of Moscow". Moscow Russia Insider's Guide. http://www.moscow-russia-insiders-guide.com/moscow-metro-2.html.

- ^ Metro 2 at www.Metro.ru (in Russian)

- ^ «Крокус» сдал «частную» станцию метро (Russian)

- ^ Map in Russian Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- ^ http://metro.molot.ru/img/genplan_71.gif

- ^ http://www.metro.ru/map/1989/metro.ru-1989map-big3.gif

- ^ a b http://engl.mosmetro.ru/pages/page_0.php?id_page=8

- ^ "Moscow Metro: the World’s First Major Transport System to operate fully contactless with NXP’s MIFARE Technology". NXP Semiconductors. http://www.nxp.com/news/content/file_1518.html. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ^ "Безналичная система оплаты проезда". Moscow metro. http://old.mosmetro.ru/pages/page_0.php?id_page=779. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ http://engl.mosmetro.ru/pages/page_1.php?id_page=56&id_text=956

- ^ Official Metro statistics

- ^ "Новости подземки" (in Russian). Lenta.ru. 22 December 2003. http://lenta.ru/articles/2003/12/22/metro/_Printed.htm. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "Terrorism: an appetite for killing for political purposes". Pravda.ru. 11 September 2006. http://english.pravda.ru/print/world/americas/84373-terrorism-0. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- ^ "Взрыв на Арбатско-Покровской линии в 1977г." (in Russian). metro.molot.ru. http://metro.molot.ru/crash_izm.shtml. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "7 Die in Moscow Subway Fire". UPI (The New York Times). 12 June 1981. http://www.nytimes.com/1981/06/12/world/7-die-in-moscow-subway-fire.html. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ^ "Авария эскалатора на станции "Авиамоторная"" (in Russian). metro.molot.ru. http://metro.molot.ru/crash_avia.shtml. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Взрыв на Замоскворецкой линии" (in Russian). metro.molot.ru. http://metro.molot.ru/crash_zamoskv2.shtml.

- ^ a b Grashchenkov, Ilya (25 May 2005). "Как работает московское метро. Список закрытых станций" (in Russian). Yтро.ru. http://pda.utro.ru/articles/2005/05/25/441638.shtml. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ Moscow Metro Tunnel Collapses on Train; Nobody Hurt

- ^ a b "38 killed in Moscow metro suicide attacks". RTÉ. 2010-03-29. http://rte.ie/news/2010/0329/russia.html. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ^ "Islamophobia on the rise after Moscow Metro attacks". AsiaNews. http://asianews.it/view4print.php?l=en&art=18060. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

External links

- Official website

- Way system map of the Moscow Metro

- Moscow Metro 2 – The Dark Legend of Moscow

- Detailed Schema of Metro Stations on Google Map (English)

- Moscow Subway News, Changes in Service (English)

- Moscow Metro Tips with Virtual Tour (English)

Lines of the Moscow Metro

Sokolnicheskaya

Koltsevaya

Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya

Zamoskvoretskaya

Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya

Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya

Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya

Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya

Kakhovskaya

Filyovskaya

Kalininskaya

Butovskaya Lines under construction or proposed [1] Kalininsko-Solntsevskaya Line · Third Interchange Circuit · Kozhukhovskaya Line List of Moscow metro stations Rapid transit in the former Soviet Union Metros* Moscow · St. Petersburg · Kiev · Tbilisi · Baku · Kharkiv · Tashkent · Yerevan · Minsk · Nizhny Novgorod · Novosibirsk · Samara · Yekaterinburg · Dnipropetrovsk · KazanMetrotrams Monorail Cave railroad Under construction Planned Abandoned * Listed in order of opening.Categories:- Moscow Metro

- Transport in Moscow

- Underground rapid transit in Russia

- Rapid transit in Russia

- 1935 establishments in Russia

- Transport in Moscow Oblast

- Electric railways in Russia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.