- Nerthus

-

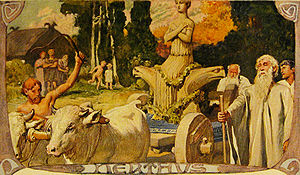

In Germanic paganism, Nerthus is a goddess associated with fertility. Nerthus is attested by Tacitus, the first century AD Roman historian, in his Germania. Various theories exist regarding the goddess and her potential later traces amongst the Germanic tribes. The minor planet 601 Nerthus is named after Nerthus.

Contents

Etymology

Nerthus is often identified with the Vanr Njörðr who is attested in various 13th century Old Norse works and in numerous Scandinavian place names. The connection between the two is due to the linguistic relationship between Njörðr and the reconstructed Proto-Germanic *Nerþuz,[1] "Nerthus" being the feminine, Latinized form of what Njörðr would have looked like around 100 CE.[2] This has led to theories about the relation of the two, including that Njörðr may have once been a hermaphroditic deity or, generally considered more likely, that the name may indicate an otherwise unattested divine brother and sister pair such as the Vanir deities Freyja and Freyr.[1] Connections have been proposed between the unnamed mother of Freyja and Freyr and the sister of Njörðr mentioned in Lokasenna and Nerthus.[3]

Germania

In chapter 40 of his Germania, Roman historian Tacitus writes that beside the Langobardi dwell seven Germanic tribes; the Reudigni, Aviones, Anglii, Varini, Eudoses, Suarines, and Nuitones. The seven tribes are surrounded by rivers and forests and, according to Tacitus, there is nothing particularly worthy of comment about them as individuals, yet they are particularly distinguished in that they all worship the goddess Nerthus, and provides an account of veneration of the goddess among the groups. The chapter reads as follows:

Latin:

- Contra Langobardos paucitas nobilitat: plurimis ac valentissimis nationibus cincti non per obsequium, sed proeliis ac periclitando tuti sunt. Reudigni deinde et Aviones et Anglii et Varini et Eudoses et Suardones et Nuithones fluminibus aut silvis muniuntur. Nec quicquam notabile in singulis, nisi quod in commune Nerthum, id est Terram matrem, colunt eamque intervenire rebus hominum, invehi populis arbitrantur. Est in insula Oceani castum nemus, dicatumque in eo vehiculum, veste contectum; attingere uni sacerdoti concessum. Is adesse pentrali deam intellegit vectamque bubus feminis multa cum veneratione prosequitur. Laeti tunc dies, festa loca, quaecumque adventu hospitioque dignatur. Non bella ineunt, non arma sumunt; clausum omne ferrum; pax et quies tunc tantum nota, tunc tantum amata, donec idem sacerdos satiatam conversatione mortalium deam templo reddat. Mox vehiculum et vestes et, si creder velis, numen ipsum secreto lacu abluitur. Servi ministrant, quos statim idem lacus haurit. Arcanus hinc terror sanctaque ignorantia, quid sit illud, quod tantum perituri vident.[4]

A. R. Birley translation:

- By contrast, the Langobardi are distinguished by being few in number. Surrounded by many might peoples they have protected themselves not by submissiveness but by battle and boldness. Next to them come the Ruedigni, Aviones, Anglii, Varini, Eudoses, Suarines, and Huitones, protected by river and forests. There is nothing especially noteworthy about these states individually, but they are distinguished by a common worship of Nerthus, that is, Mother Earth, and believes that she intervenes in human affairs and rides through their peoples. There is a sacred grove on an island in the Ocean, in which there is a consecrated chariot, draped with cloth, where the priest alone may touch. He perceives the presence of the goddess in the innermost shrine and with great reverence escorts her in her chariot, which is drawn by female cattle. There are days of rejoicing then and the countryside celebrates the festival, wherever she designs to visit and to accept hospitality. No one goes to war, no one takes up arms, all objects of iron are locked away, then and only then do they experience peace and quiet, only then do they prize them, until the goddess has had her fill of human society and the priest brings her back to her temple. Afterwards the chariot, the cloth, and, if one may believe it, the deity herself are washed in a hidden lake. The slaves who perform this office are immediately swallowed up in the same lake. Hence arises dread of the mysterious, and piety, which keeps them ignorant of what only those about to perish may see.[5]

J. B. Rives translation:

- The Langobardi, by contrast, are distinguished by the fewness of their numbers. Ringed round as they are by many mighty peoples, they find safety not in obsequiousness but in battle and its perils. After them come the Reudingi, Aviones, Anglii, Varini, Eudoses, Suarini and Nuitones, behind their ramparts of rivers and woods. There is nothing noteworthy about these peoples individually, but they are distinguished by a common worship of Nerthus, or Mother Earth. They believe that she interests herself in human affairs and rides among their peoples. In an island of the Ocean stands a sacred grove, and in the grove a concentrated cart, draped with cloth, which none but the priest may touch. The priest perceives the presence of the goddess in this holy of holies and attends her, in deepest reverence, as her cart is drawn by heifers. Then follow days of rejoicing and merry-making in every place that she designs to visit and be entertained. No one goes to war, no one takes up arms; every object of iron is locked away; then, and only then, are peace and quiet known and loved, until the priest again restores the goddess to her temple, when she has had her fill of human company. After that the cart, the cloth and, if you care to believe it, the goddess herself are washed in clean in a secluded lake. This service is performed by slaves who are immediately afterwards drowned in the lake. Thus mystery begets terror and pious reluctance to ask what the sight can be that only those doomed to die may see.[6]

General theories

A number of theories have been proposed regarding the figure of Nerthus, including the location of the events described, relations to other known deities and her role amongst the Germanic tribes.

Later traces

It has been theorized that evidence of the veneration of a mother goddess, representing the earth, survived among the Angles (Tacitus' Anglii) into Christian times as evidenced in the partially-Christianized pagan Anglo-Saxon Æcerbot ritual.[7]

Location

A number of scholars have proposed a potential location of Tacitus' account of Nerthus as on the island of Zealand in Denmark.[8][9] Reasoning behind this notion is the linking the name Nerthus with the medieval place name Niartharum (now called Naerum) located on Zealand. Further justification is given that Lejre, the seat of the ancient kings of Denmark, also is located on Zealand. Nerthus is then commonly compared to Gefjun who is said to have plowed the island of Zealand from Sweden in Gylfaginning.[10]

Identity

Jacob Grimm (1835) first identified Nerthus as the Germanic earth-mother who appeared under such names as Erda, Erce, Fru Gaue, Fjörgyn, Frau Holda and Hluodana.[11]

Nerthus typically is identified as a Vanir goddess. Her wagon tour has been likened to several archeological wagon finds and legends of deities parading in wagons. Terry Gunnell and many others have noted various archaeological finds of ritual wagons in Denmark dating from 200 AD and the Bronze Age. Such a ceremonial wagon, incapable of making turns, was discovered in the Oseberg ship find. Two of the most famous literary examples occur in the Icelandic family sagas. The Vanir god Freyr is said to ride in a wagon annually through the country accompanied by a priestess to bless the fields, according to a late story titled Hauks þáttr hábrókar in the 14th century Flateyjarbók manuscript. In the same source, King Eric of Sweden is said to consult a god named Lytir, whose wagon was brought to his hall in order to perform a divination ceremony.[8]

H.E. Davidson draws a parallel between these incidents and the Tacitus' account of Nerthus, suggesting that in addition a neck-ring wearing female figure "kneeling as if to drive a chariot" also dates from the Bronze Age. She posits that the evidence suggests that similar customs as detailed in Tacitus' account continued to exist during the close of the pagan period through worship of the Vanir.[8]

While the connection between Nerthus and Njörðr is generally accepted, a few scholars have argued against it. Edgar Polomé argued that Njörðr and Nerthus come from different roots, adding that "Nerthus and Njörðr are two separate divine entities, whatever similarity their names show."[12] Lotte Motz proposed that the Germanic goddess described by Tacitus may not have been called Nerthus at all, stating her opinion that Grimm selected the name Nerthus from among the manuscript readings precisely because it bore an etymological resemblance to Njörðr.[13]

John Grigsby (2005) theorizes that the overthrowing of the Vanir religion by that of the Æsir is remembered in the Old English poem Beowulf, that Grendel's mother is derived from the lake-dwelling Nerthus, and that Beowulf's victory over her is symbolic of the ending of the Vanir cult in Denmark by the Odin-worshiping Danes.[14]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Simek (2007:234)

- ^ Lindow (2001:237-238)

- ^ Orchard (1997:117-118).

- ^ Stuart (1916:20).

- ^ Birley (1999:58).

- ^ Rives (2010). Pages unnumbered; Germania chapter 40.

- ^ Davidson (1998).

- ^ a b c Davidson (1964).

- ^ Chadwick (1907:267-268).

- ^ Chadwick (1907:289).

- ^ Deutsche Mythologie, Vol. I, ch. 13; translated as Teutonic Mythology, by James Steven Stalleybrass, 1883, pp. 251-253.

- ^ Polomé, (1999:143-154).

- ^ Motz, Lotte (1992:1-18).

- ^ Grigsby(2005).

References

- Birley, A. R. (Trans.) (1999). Agricola and Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283300-6

- Chadwick, Hector Munro (1907). The Origin of the English Nation. ISBN 0941694097

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1990). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013627-4.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1998). Roles of the Northern Goddess. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13611-3

- Foulke, William Dudley (Trans.) (2003). History of the Lombards: Paul the Deacon. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812210794

- Grigsby, John (2005). Beowulf and Grendel. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 1842931539

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- McKinnell, John (2005). Meeting the Other in Norse Myth in Legends. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 1843840421

- Motz, Lotte (1992). The Goddess Nerthus: A New Approach. Amsterdamer Beiträge zur Älteren Germanistik 36.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0 304 34520 2

- Polomé, Edgar (1999). "Nerthus/Njorðr and Georges Dumézil", Mankind Quarterly 40:2.

- Rives, J. B. (Trans.) (2010). Agricola and Germania. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-045540-3

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer ISBN 0859915131

- Stuart, Duane Reed (1916). Tacitus - Germania. The Macmillan Company.

- Turville-Petre, E. O. G (1969). "Fertility of Beast and Soil" as collected in Polemé, Edgar (Editor). Old Norse Literature and Mythology: A Symposium. University of Texas Press

Germanic peoples Languages Prehistory Roman Iron Age Migration Period Germanic Iron Age · Alamanni · Anglo-Saxons (Angles · Jutes · Saxons) · Burgundians · Dani · Franks · Frisii · Geats · Goths (Visigoths · Ostrogoths · Valagoths · Gothic Wars) · Gotlanders · Lombards · Suebi · Suiones · Vandals · Varangians · Christianization of the Germanic peoples · RomanizationSociety and culture Mead hall · Poetry · Migration Period art · Runes (Runic calendar) · Sippe · Law (Lawspeaker · Thing) · Calendar · King · Names · Numbers · Romano-Germanic cultureReligion Wodanaz · Veleda · Tuisto · Mannus · Paganism (Anglo-Saxon · Continental Germanic mythology · Frankish · Norse) · Christianity (Arianism · Gothic)Dress Warfare Burial practices List of Germanic peoples · Portal:Ancient Germanic cultureCategories:- Fertility goddesses

- Germanic deities

- English goddesses

- Earth goddesses

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.