- Thai language

-

Thai ภาษาไทย phasa thai Pronunciation [pʰāːsǎːtʰāj] Spoken in Thailand, Northern Malaysia, Cambodia, Southern Burma, Laos, USA, Canada, France, England Native speakers 26 million (2001)

Total: 60 million (2001)Language family Writing system Thai script Official status Official language in Thailand Regulated by The Royal Institute Language codes ISO 639-1 th ISO 639-2 tha ISO 639-3 tha Linguasphere 47-AAA-b This page contains Indic text. Without rendering support you may see irregular vowel positioning and a lack of conjuncts. More... This page contains IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. Thai (ภาษาไทย Phasa Thai[1] [pʰāːsǎːtʰāj] (

listen)) is the national and official language of Thailand and the native language of the Thai people, Thailand's dominant ethnic group. Thai is a member of the Tai group of the Tai–Kadai language family. Historical linguists have been unable to definitively link the Tai–Kadai languages to any other language family. Some words in Thai are borrowed from Pali, Sanskrit and Old Khmer. It is a tonal and analytic language. Thai also has a complex orthography and relational markers. Thai is mutually intelligible with Lao,[2] whereas the Isaan dialect is almost the same as Lao.

listen)) is the national and official language of Thailand and the native language of the Thai people, Thailand's dominant ethnic group. Thai is a member of the Tai group of the Tai–Kadai language family. Historical linguists have been unable to definitively link the Tai–Kadai languages to any other language family. Some words in Thai are borrowed from Pali, Sanskrit and Old Khmer. It is a tonal and analytic language. Thai also has a complex orthography and relational markers. Thai is mutually intelligible with Lao,[2] whereas the Isaan dialect is almost the same as Lao.Contents

Languages and dialects

Standard Thai, also known as Central Thai or Siamese, is the official language of Thailand, spoken by over 20 million people (2000),[3] including speakers of Bangkok Thai (the latter is sometimes considered a separate dialect, and sometimes the standard dialect).[4] Khorat Thai is spoken by about 400,000 (1984) in Nakhon Ratchasima; it occupies a linguistic position somewhere between Central Thai and Isan on a dialect continuum, and may be considered a variant of either. A majority of the people in the Isan region of Thailand speak a dialect of the Lao language, which has influenced the Central Thai dialect.[citation needed]

In addition to Standard Thai, Thailand is home to other related Tai languages, including:

- Isan (Northeastern Thai), the language of the Isan region of Thailand, a socio-culturally distinct Thai-Lao hybrid dialect which is written with the Thai script. It is spoken by about 15 million people (1983).

- Galung language, spoken in Nakhon Phanom Province of Northeast Thailand.

- Northern Thai (Phasa Nuea, Lanna, Kam Mueang, or Thai Yuan), spoken by about 6 million (1983) in the formerly independent kingdom of Lanna (Chiang Mai).

- Nyaw language, spoken mostly in Nakhon Phanom Province, Sakhon Nakhon Province, Udon Thani Province of Northeast Thailand.

- Phuan, spoken by an unknown number of people in central Thailand, Isan and Northern Laos.

- Phu Thai, spoken by about 156,000 around Nakhon Phanom Province (1993).

- Shan (Thai Luang, Tai Long, Thai Yai), spoken by about 56,000 in north-west Thailand along the border with the Shan States of Burma (1993).

- Song, spoken by about 20,000 to 30,000 in central and northern Thailand (1982).

- Southern Thai (Phasa Tai), spoken by about 5 million (1990).

- Thai Dam, spoken by about 20,000 (1991) in Isan and Saraburi Province.

- Lü (Tai Lue, Dai), spoken by about 78,000 (1993) in northern Thailand.

Statistics are from Ethnologue 2003-10-4.

Many of these languages are spoken by larger numbers outside of Thailand.[citation needed] Most speakers of dialects and minority languages speak Central Thai as well, since it is the language used in schools and universities all across the kingdom.

Numerous languages not related to Thai are spoken within Thailand by ethnic minority hill tribespeople. These languages include Hmong–Mien (Yao), Karen, Lisu, and others.

Standard Thai is composed of several distinct registers, forms for different social contexts:

- Street or common Thai (ภาษาพูด, spoken Thai): informal, without polite terms of address, as used between close relatives and friends.

- Elegant or formal Thai (ภาษาเขียน, written Thai): official and written version, includes respectful terms of address; used in simplified form in newspapers.

- Rhetorical Thai: used for public speaking.

- Religious Thai: (heavily influenced by Sanskrit and Pāli) used when discussing Buddhism or addressing monks.

- Royal Thai (ราชาศัพท์): (influenced by Khmer) used when addressing members of the royal family or describing their activities.

Most Thais can speak and understand all of these contexts. Street and elegant Thai are the basis of all conversations;[citation needed] rhetorical, religious and royal Thai are taught in schools as the national curriculum.

Script

Main article: Thai scriptMany scholars believe that the Thai script is derived from the Khmer script, which is modeled after the Brahmic script from the Indic family. However, in appearance, Thai is closer to Thai Dam script, which may have the same Indian origins as the Khmer script. The language and its script[citation needed] are closely related to the Lao language and script. Most literate Lao are able to read and understand Thai, as more than half of the Thai vocabulary, grammar, intonation, vowels and so forth are common with the Lao language. Much like the Burmese adopted the Mon script (which also has Indic origins), the Thais adopted and modified the Khmer script to create their own writing system. While the oldest known inscription in the Khmer language dates from 611 CE, inscriptions in Thai writing began to appear around 1292 CE. Notable features include:

- It is an abugida script, in which the implicit vowel is a short /a/ in a syllable without final consonant and a short /o/ in a syllable with final consonant.

- Tone markers are placed above the final onset consonant of the syllable.

- Vowels sounding after a consonant are nonsequential: they can be located before, after, above or below the consonant, or in a combination of these positions.

Transcription

There is no universal standard for transcribing Thai into the Latin alphabet. For example, the name of King Rama IX, the present monarch, is transcribed variously as Bhumibol, Phumiphon, phuuM miH phohnM, or many other versions. Guide books, text books and dictionaries may each follow different systems. For this reason, most language courses recommend that learners master the Thai script.

What comes closest to a standard is the Royal Thai General System of Transcription (RTGS), published by the Thai Royal Institute.[5] This system is increasingly used in Thailand by central and local governments,[citation needed] especially for road signs. Its main drawbacks are that it does not indicate tone or vowel length. Retro-transliteration, that is, reconstruction of Thai spelling from RTGS romanisation, is not possible.

Transliteration

The ISO published an international standard for the transliteration of Thai into Roman script in September 2003 (ISO 11940) [2]. By adding diacritics to the Latin letters, it makes the transcription reversible, making it a true transliteration. This system is intended for academic use, but is rarely used in any context.[citation needed]

Grammar

Main article: Thai grammarFrom the perspective of linguistic typology, Thai can be considered to be an analytic language. The word order is subject–verb–object, although the subject is often omitted. Thai pronouns are selected according to the gender and relative status of speaker and audience.

Adjectives and adverbs

There is no morphological distinction between adverbs and adjectives. Many words can be used in either function. They follow the word they modify, which may be a noun, verb, or another adjective or adverb. Intensity can be expressed by a duplicated word, which is used to mean "very" (with the first occurrence at a higher pitch) or "rather" (with both at the same pitch) (Higbie 187-188). Usually, only one word is duplicated per clause.

- คนอ้วน (khon uan, [kʰon ʔûan ]) a fat person

- คนอ้วน ๆ (khon uan uan, [kʰon ʔûan ʔûan]) a very/rather fat person

- คนที่อ้วนเร็วมาก (khon uan rew mak, [khon thîː ʔûan rew mâːk]) a person who becomes/became fat very quickly

- คนที่อ้วนเร็วมาก ๆ (khon uan rew mak mak, [khon thîː ʔûan rew mâːk mâːk]) a person who becomes/became fat very very quickly

Comparatives take the form "A X กว่า B" (kwa, [kwàː]), A is more X than B. The superlative is expressed as "A X ที่สุด" (thi sut, [tʰîːsùt]), A is most X.

- เขาอ้วนกว่าฉัน (khao uan kwa chan, [kʰǎw ʔûan kwàː tɕ͡ʰǎn]) S/he is fatter than me.

- เขาอ้วนที่สุด (khao uan thi sut, [kʰǎw ʔûan tʰîːsùt]) S/he is the fattest (of all).

Because adjectives can be used as complete predicates, many words used to indicate tense in verbs (see Verbs:Tense below) may be used to describe adjectives.

- ฉันหิว (chan hiu, [tɕ͡ʰǎn hǐw]) I am hungry.

- ฉันจะหิว (chan cha hiu, [tɕ͡ʰǎn tɕ͡àʔ hǐw]) I will be hungry.

- ฉันกำลังหิว (chan kamlang hiu, [tɕ͡ʰǎn kamlaŋ hǐw]) I am hungry right now.

- ฉันหิวแล้ว (chan hiu laeo, [tɕ͡ʰǎn hǐw lɛ́ːw]) I am already hungry.

-

- Remark ฉันหิวแล้ว mostly means "I am hungry right now" because normally, แล้ว ([lɛ́ːw]) is a past-tense marker, but แล้ว has many other uses as well. For example, in the sentence, แล้วเธอจะไปไหน ([lɛ́ːw tʰɤː tɕ͡àʔ paj nǎj]): So where are you going?, แล้ว ([lɛ́ːw]) is used as a discourse particle.

Verbs

Verbs do not inflect (i.e. do not change with person, tense, voice, mood, or number) nor are there any participles. Duplication conveys the idea of doing the verb intensively.

The passive voice is indicated by the insertion of ถูก (thuk, [tʰùːk]) before the verb. For example:

- เขาถูกตี (khao thuk ti, [kʰǎw tʰùːk tiː]), He is hit. This describes an action that is out of the receiver's control and, thus, conveys suffering.

To convey the opposite sense, a sense of having an opportunity arrive, ได้ (dai, [dâj], can) is used. For example:

- เขาจะได้ไปเที่ยวเมืองลาว (khao cha dai pai thiao mueang lao, [kʰǎw t͡ɕaʔ dâj paj tʰîow mɯːaŋ laːw]), He gets to visit Laos.

Note, dai ([dâj] and [dâːj]), though both spelled ได้ , convey two separate meanings. The short vowel dai ([dâj]) conveys an opportunity has arisen and is placed before the verb. The long vowel dai ([dâːj]) is placed after the verb and conveys the idea that one has been given permission or one has the ability to do something. Also see the past tense below.

- เขาตีได้ (khao ti dai, [kʰǎw tiː dâːj]), He is/was allowed to hit or He is/was able to hit

Negation is indicated by placing ไม่ (mai,[mâj] not) before the verb.

- เขาไม่ตี, (khao mai ti) He is not hitting. or He doesn't hit.

Tense is conveyed by tense markers before or after the verb.

- Present can be indicated by กำลัง (kamlang, [kamlaŋ], currently) before the verb for ongoing action (like English -ing form), by อยู่ (yu, [jùː]) after the verb, or by both. For example:

- เขากำลังวิ่ง (khao kamlang wing, [kʰǎw kamlaŋ wîŋ]), or

- เขาวิ่งอยู่ (khao wing yu, [kʰǎw wîŋ jùː]), or

- เขากำลังวิ่งอยู่ (khao kamlang wing yu, [kʰǎw kamlaŋ wîŋ jùː]), He is running.

- Future can be indicated by จะ (cha, [t͡ɕaʔ], will) before the verb or by a time expression indicating the future. For example:

- เขาจะวิ่ง (khao cha wing, [kʰǎw t͡ɕaʔ wîŋ]), He will run or He is going to run

- Past can be indicated by ได้ (dai, [dâːj]) before the verb or by a time expression indicating the past. However, แล้ว (laeo, :[lɛ́ːw], already) is more often used to indicate the past tense by being placed behind the verb. Or, both ได้ and แล้ว are put together to form the past tense expression, i.e. Subject + ได้ + Verb + แล้ว. For example:

- เขาได้กิน (khao dai kin, [kʰǎw dâːj kin]), He ate

- เขากินแล้ว (khao kin laeo, [kʰǎw kin lɛ́ːw], He (already) ate or He's already eaten

- เขาได้กินแล้ว (khao dai kin laeo, [kʰǎw dâːj kin lɛ́ːw]), He (already) ate or He's already eaten

Thai exhibits serial verb constructions, where verbs are strung together. Some word combinations are common and may be considered set phrases.

- เขาไปกินข้าว (khao pai kin khao, [kʰǎw paj kin kʰâːw]) He went out to eat, literally He go eat food

- ฉันฟังไม่เข้าใจ (chan fang mai khao chai, [tɕ͡ʰǎn faŋ mâj kʰâw tɕ͡aj]) I don't understand what was said, literally I listen not understand

- เข้ามา (khao ma, [kʰâw maː]) Come in, literally enter come

- ออกไป! (ok pai, [ʔɔ̀ːk paj]) Leave! or Get out!, literally exit go

Nouns

Nouns are uninflected and have no gender; there are no articles.

Nouns are neither singular nor plural. Some specific nouns are reduplicated to form collectives: เด็ก (dek, child) is often repeated as เด็กๆ (dek dek) to refer to a group of children. The word พวก (phuak, [pʰûak]) may be used as a prefix of a noun or pronoun as a collective to pluralize or emphasise the following word. (พวกผม, phuak phom, [pʰûak pʰǒm], we, masculine; พวกเรา phuak rao, [pʰûak raw], emphasised we; พวกหมา phuak ma, (the) dogs) Plurals are expressed by adding classifiers, used as measure words (ลักษณนาม), in the form of noun-number-classifier (ครูห้าคน, "teacher five person" for "five teachers"). While in English, such classifiers are usually absent ("four chairs") or optional ("two bottles of beer" or "two beers"), a classifier is almost always used in Thai (hence "chair four item" and "beer two bottle").

Pronouns

Subject pronouns are often omitted, with nicknames used where English would use a pronoun. See informal and formal names for more details. Pronouns, when used, are ranked in honorific registers, and may also make a T–V distinction in relation to kinship and social status. Specialised pronouns are used for those with royal and noble titles, and for clergy. The following are appropriate for conversational use:

Word RTGS IPA Meaning ผม phom [pʰǒm] I/me (masculine; formal) ดิฉัน dichan [dìʔt͡ɕʰán]) I/me (feminine; formal) ฉัน chan [t͡ɕʰǎn] I/me (masculine or feminine; informal) คุณ khun [kʰun] you (polite) ท่าน than [tʰân] you (polite to a person of high status) เธอ thoe [tʰɤː] you (informal), she/her (informal) เรา rao [raw] we/us, I/me/you (casual) เขา khao [kʰǎw] he/him, she/her มัน man [man] it, he/she (sometimes casual or offensive; if used to refer to a person) พวกเขา phuak khao [pʰûak kʰǎw] they/them พี่ phi [pʰîː] older brother, sister (also used for older acquaintances) น้อง nong [nɔːŋ] younger brother, sister (also used for younger acquaintances) ลูกพี่ ลูกน้อง luk phi luk nong [lûːk pʰîː lûːk nɔ́ːŋ] first cousin (male or female) The reflexive pronoun is ตัวเอง (tua eng), which can mean any of: myself, yourself, ourselves, himself, herself, themselves. This can be mixed with another pronoun to create an intensive pronoun, such as ตัวผมเอง (tua phom eng, lit: I myself) or ตัวคุณเอง (tua khun eng, lit: you yourself).

Thai does not have a separate possessive pronoun. Instead, possession is indicated by the particle ของ (khong). For example, "my mother" is แม่ของผม (mae khong phom, lit: mother of I). This particle is often implicit, so the phrase is shortened to แม่ผม (mae phom).

Thai has many more pronouns than those listed above. Their usage is full of nuances. For example:

- "ผม เรา ฉัน ดิฉัน ชั้น หนู กู ข้า กระผม ข้าพเจ้า กระหม่อม อาตมา กัน ข้าน้อย ข้าพระพุทธเจ้า อั๊ว เค้า" all translate to "I", but each expresses a different gender, age, politeness, status, or relationship between speaker and listener.

- เรา (rao) can be first person (I), second person (you), or both (we), depending on the context.

- When speaking to someone older, หนู (nu) is a feminine first person (I). However, when speaking to someone younger, the same word หนู is a neuter second person (you).

- The second person pronoun เธอ (thoe) (lit: you) is semi-feminine. It is used only when the speaker or the listener (or both) are female. Males usually don't address each other by this pronoun.

- Both คุณ (khun) and เธอ (thoe) are polite neuter second person pronouns. However, คุณเธอ (khun thoe) is a feminine derogative third person.

- Instead of a second person pronoun such as "คุณ" (you), it's much more common for unrelated strangers to call each other "พี่ น้อง ลุง ป้า น้า อา ตา ยาย" (brother/sister/aunt/uncle/granny).

- To express deference, the second person pronoun is sometimes replaced by a profession, similar to how, in English, presiding judges are always addressed as "your honor" rather than "you". In Thai, students always address their teachers by "ครู คุณครู อาจารย์" (each means teacher) rather than คุณ (you). Teachers, monks, and doctors are almost always addressed this way.

Particles

The particles are often untranslatable words added to the end of a sentence to indicate respect, a request, encouragement or other moods (similar to the use of intonation in English), as well as varying the level of formality. They are not used in elegant (written) Thai. The most common particles indicating respect are ครับ (khrap, [kʰráp], with a high tone) for a man, and ค่ะ (kha, [kʰâ], with a falling tone) for a woman; these can also be used to indicate an affirmative, though the ค่ะ (falling tone) is changed to a คะ (high tone).

Other common particles are:

Word RTGS IPA Meaning จ๊ะ cha [t͡ɕáʔ] indicating a request จ้ะ, จ้า or จ๋า cha [t͡ɕâː] indicating emphasis ละ or ล่ะ la [láʔ] indicating emphasis สิ si [sìʔ] indicating emphasis or an imperative นะ na [náʔ] softening; indicating a request Phonology

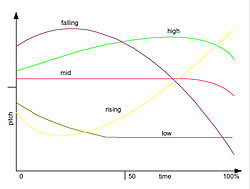

Tones

There are five phonemic tones: mid, low, falling, high and rising, sometimes referred to in older reference works as rectus, gravis, circumflexus, altus and demissus, respectively.[6] The table shows an example of both the phonemic tones and their phonetic realization, in the IPA.

Tone Thai Example Phonemic Phonetic Example meaning in English mid สามัญ นา /nāː/ [naː˧] paddy field low เอก หน่า /nàː/ [naː˩] (a nickname) falling โท หน้า /nâː/ [naː˥˩] face high ตรี น้า /náː/ [naː˧˥] or [naː˥] aunt/uncle (younger than one's parents) rising จัตวา หนา /nǎː/ [naː˩˩˦] or [naː˩˦] thick Consonants

Initials

Thai distinguishes among three voice/aspiration patterns for plosive consonants:

- unvoiced, unaspirated

- unvoiced, aspirated

- voiced, unaspirated

Where English has only a distinction between the voiced, unaspirated /b/ and the unvoiced, aspirated /pʰ/, Thai distinguishes a third sound that is neither voiced nor aspirated, which occurs in English only as an allophone of /p/, approximately the sound of the p in "spin". There is similarly an alveolar /t/, /tʰ/, /d/ triplet. In the velar series there is a /k/, /kʰ/ pair and in the postalveolar series the /t͡ɕ/, /t͡ɕʰ/ pair.

In each cell below, the first line indicates International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), the second indicates the Thai characters in initial position (several letters appearing in the same box have identical pronunciation).

Bilabial Labio-

dentalAlveolar Post-

alveolarPalatal Velar Glottal Nasal [m]

ม[n]

ณ,น[ŋ]

งPlosive [p]

ป[pʰ]

ผ,พ,ภ[b]

บ[t]

ฏ,ต[tʰ]

ฐ,ฑ,ฒ,ถ,ท,ธ[d]

ฎ,ด[k]

ก[kʰ]

ข,ฃ,ค,ฅ,ฆ*[ʔ]

อ**Fricative [f]

ฝ,ฟ[s]

ซ,ศ,ษ,ส[h]

ห,ฮAffricate [t͡ɕ]

จ[t͡ɕʰ]

ฉ, ช, ฌTrill [r]

รApproximant [j]

ญ,ย[w]

วLateral

approximant[l]

ล,ฬ- * ฃ and ฅ are no longer used. Thus, modern Thai is said to have 42 consonant letters.

- ** Initial อ is silent and therefore considered as glottal plosive.

Finals

Although the overall 44 Thai consonant letters provide 21 sounds in case of initials, the case for finals is different. For finals, only eight sounds, as well as no sound, are used. To demonstrate, at the end of a syllable, บ (/b/) and ด (/d/) are devoiced, becoming pronounced as /p/ and /t/ respectively.

Of the consonant letters, excluding the disused ฃ and ฅ, seven (ฉ ฌ ผ ฝ ห อ ฮ) cannot be used as a final and the other 35 are grouped as following.

Bilabial Labio-

dentalAlveolar Post-

alveolarPalatal Velar Glottal Nasal [m]

ม[n]

ญ,ณ,น,ร,ล,ฬ[ŋ]

งPlosive [p]

บ,ป,พ,ฟ,ภ[t]

จ,ช,ซ,ฎ,ฏ,ฐ,ฑ,ฒ,

ด,ต,ถ,ท,ธ,ศ,ษ,ส[k]

ก,ข,ค,ฆ[ʔ]* Fricative Affricate Trill Approximant [j]

ย[w]

วLateral

approximant- * The glottal plosive appears at the end when no final follows a short vowel

Clusters

In Thai, each syllable in a word is considered separate from the others, so combinations of consonants from adjacent syllables are never recognised as a cluster.

Thai has very limited number of clusters. Original Thai vocabulary introduces only 11 combined patterns:

- /kr/, /kl/, /kw/

- /kʰr/, /kʰl/, /kʰw/

- /pr/, /pl/

- /pʰr/, /pʰl/

- /tr/

The number of clusters increases when a few more combinations are presented in loanwords such as อินทรา (/intʰraː/, from Sanskrit indrā) in which extraordinary /tʰr/ is found. However, it can be observed that Thai language supports only those in initial position, with either /r/, /l/, or /w/ as the second consonant sound and not more than two sounds at a time.

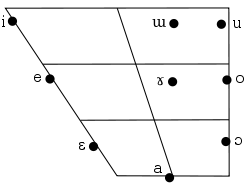

Vowels

The basic vowels of the Thai language, from front to back and close to open, are given in the following table. The top entry in every cell is the symbol from the International Phonetic Alphabet, the second entry gives the spelling in the Thai alphabet, where a dash (–) indicates the position of the initial consonant after which the vowel is pronounced. A second dash indicates that a final consonant must follow.

Front Back unrounded unrounded rounded short long short long short long Close /i/

-ิ/iː/

-ี/ɯ/

-ึ/ɯː/

-ื-/u/

-ุ/uː/

-ูClose-mid /e/

เ-ะ/eː/

เ-/ɤ/

เ-อะ/ɤː/

เ-อ/o/

โ-ะ/oː/

โ-Open-mid /ɛ/

แ-ะ/ɛː/

แ-/ɔ/

เ-าะ/ɔː/

-อOpen /a/

-ะ, -ั-/aː/

-าThe vowels each exist in long-short pairs: these are distinct phonemes forming unrelated words in Thai,[7] but usually transliterated the same: เขา (khao) means "he" or "she", while ขาว (khao) means "white".

The long-short pairs are as follows:

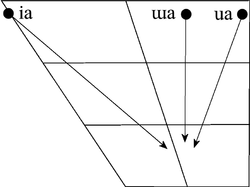

Long Short Thai IPA Example Thai IPA Example –า /aː/ ฝาน /fǎːn/ 'to slice' –ะ /a/ ฝัน /fǎn/ 'to dream' –ี /iː/ กรีด /krìːt/ 'to cut' –ิ /i/ กริช /krìt/ 'kris' –ู /uː/ สูด /sùːt/ 'to inhale' –ุ /u/ สุด /sùt/ 'rearmost' เ– /eː/ เอน /ʔēːn/ 'to recline' เ–ะ /e/ เอ็น /ʔēn/ 'tendon, ligament' แ– /ɛː/ แพ้ /pʰɛ́ː/ 'to be defeated' แ–ะ /ɛ/ แพะ /pʰɛ́ʔ/ 'goat' –ื- /ɯː/ คลื่น /kʰlɯ̂ːn/ 'wave' –ึ /ɯ/ ขึ้น /kʰɯ̂n/ 'to go up' เ–อ /ɤː/ เดิน /dɤ̄ːn/ 'to walk' เ–อะ /ɤ/ เงิน /ŋɤ̄n/ 'silver' โ– /oː/ โค่น /kʰôːn/ 'to fell' โ–ะ /o/ ข้น /kʰôn/ 'thick (soup)' –อ /ɔː/ กลอง /klɔːŋ/ 'drum' เ–าะ /ɔ/ กล่อง /klɔ̀ŋ/ 'box' The basic vowels can be combined into diphthongs. Tingsabadh & Abramson (1993) analyze those ending in high vocoids as underlyingly /Vj/ and /Vw/. For purposes of determining tone, those marked with an asterisk are sometimes classified as long:

Long Short Thai IPA Thai IPA –าย /aːj/ ไ–*, ใ–*, ไ–ย, -ัย /aj/ –าว /aːw/ เ–า* /aw/ เ–ีย /iːa/ เ–ียะ /ia/ – – –ิว /iw/ –ัว /uːa/ –ัวะ /ua/ –ูย /uːj/ –ุย /uj/ เ–ว /eːw/ เ–็ว /ew/ แ–ว /ɛːw/ – – เ–ือ /ɯːa/ เ–ือะ /ɯa/ เ–ย /ɤːj/ – – –อย /ɔːj/ – – โ–ย /oːj/ – – Additionally, there are three triphthongs, all of which are long:

Thai IPA เ–ียว /iaw/ –วย /uaj/ เ–ือย /ɯaj/ For a guide to written vowels, see the Thai alphabet page.

Vocabulary

Other than compound words and words of foreign origin, most words are monosyllabic. Historically, words have most often been borrowed from Sanskrit and Pāli; Buddhist terminology is particularly indebted to these. Old Khmer has also contributed its share, especially in regard to royal court terminology. Since the beginning of the 20th century, however, the English language has had the greatest influence, especially for scientific and technical vocabulary. Many Teochew Chinese words are also used, some replacing existing Thai words (for example, the names of basic numbers; see also Sino-Xenic).[citation needed]

As noted above, Thai has several registers, each having certain usages, such as colloquial, formal, literary, and poetic. Thus, the word "eat" can be กิน (kin; common), แดก (daek; vulgar), ยัด (yat; vulgar), บริโภค (boriphok; formal), รับประทาน (rapprathan; formal), ฉัน (chan; religious), or เสวย (sawoei; royal).

Thailand also uses the distinctive Thai six hour clock in addition to the 24 hour clock.

See also

- Thai numerals

- Literature in Thailand

- The Royal Institute of Thailand

- Thai honorifics

Notes

- ^ Royal Thai General System of Transcription: phasa thai; ISO 11940 transliteration: p̣hās̄ʹāthịy

- ^ Ausbau and Abstand languages

- ^ Ethnologue report for Thai

- ^ Peansiri Vongvipanond (Summer 1994). "Linguistic Perspectives of Thai Culture". paper presented to a workshop of teachers of social science. University of New Orleans. p. 2. http://thaiarc.tu.ac.th/thai/peansiri.htm. Retrieved 26 April 2011. "The dialect one hears on radio and television is the Bangkok dialect, considered the standard dialect."

- ^ Royal Thai General System of Transcription, published by the Thai Royal Institute only in Thai.

- ^ Frankfurter, Oscar. Elements of Siamese grammar with appendices. American Presbyterian mission press, 1900 [1] (Full text available on Google Books)

- ^ Tingsabadh & Abramson (1993:25)

References

- อภิลักษณ์ ธรรมทวีธิกุล และ กัลยารัตน์ ฐิติกานต์นารา. 2549.“การเน้นพยางค์กับทำนองเสียงภาษาไทย” (Stress and Intonation in Thai ) วารสารภาษาและภาษาศาสตร์ ปีที่ 24 ฉบับที่ 2 (มกราคม – มิถุนายน 2549) หน้า 59-76

- สัทวิทยา : การวิเคราะห์ระบบเสียงในภาษา. 2547. กรุงเทพฯ : สำนักพิมพ์มหาวิทยาลัยเกษตรศาสตร์

- Gandour, Jack, Tumtavitikul, Apiluck and Satthamnuwong, Nakarin.1999. “Effects of Speaking Rate on the Thai Tones.” Phonetica 56, pp. 123–134.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck, 1998. “The Metrical Structure of Thai in a Non-Linear Perspective”. Papers presentd to the Fourth Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 1994, pp. 53–71. Udom Warotamasikkhadit and Thanyarat Panakul, eds. Temple,Arizona:Program for Southeast Asian Studies, Arizona State University.

- Apiluck Tumtavitikul. 1997. “The Reflection on the X’ category in Thai”. Mon–Khmer Studies XXVII, pp. 307–316.

- อภิลักษณ์ ธรรมทวีธิกุล. 2539. “ข้อคิดเกี่ยวกับหน่วยวากยสัมพันธ์ในภาษาไทย” วารสารมนุษยศาสตร์วิชาการ. 4.57-66.

- Tumtavitikul, Appi. 1995. “Tonal Movements in Thai”. The Proceedings of the XIIIth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Vol. I, pp. 188–121. Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology and Stockholm University.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck. 1994. “Thai Contour Tones”.Current Issues in Sino-Tibetan Linguistics, pp. 869–875. Hajime Kitamura et al., eds, Ozaka: The Organization Committee of the 26th Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics,National Museum of Ethnology.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck. 1993. “FO – Induced VOT Variants in Thai”. Journal of Languages and Linguistics, 12.1.34 – 56.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck. 1993. “Perhaps, the Tones are in the Consonants?” Mon–Khmer Studies XXIII, pp. 11–41.

- Higbie, James and Thinsan, Snea. Thai Reference Grammar: The Structure of Spoken Thai. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2003. ISBN 974-8304-96-5.

- Nacaskul, Karnchana, Ph.D. (ศาสตราจารย์กิตติคุณ ดร.กาญจนา นาคสกุล) Thai Phonology, 4th printing. (ระบบเสียงภาษาไทย, พิมพ์ครั้งที่ 4) Bangkok: Chulalongkorn Press, 1998. ISBN 978-9-746-39375-1.

- Nanthana Ronnakiat, Ph.D. (ดร.นันทนา รณเกียรติ) Phonetics in Principle and Practical. (สัทศาสตร์ภาคทฤษฎีและภาคปฏิบัติ) Bangkok: Thammasat University, 2005. ISBN 974-571-929-3.

- Segaller, Denis. Thai Without Tears: A Guide to Simple Thai Speaking. Bangkok: BMD Book Mags, 1999. ISBN 974-87115-2-8.

- Smyth, David. Thai: An Essential Grammar. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-22614-7.

- Tingsabadh, M.R. Kalaya; Abramson, Arthur (1993), "Thai", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 23 (1): 24–28

External links

Glossaries and word lists

- Thai phrasebook in Wikitravel

- Thai Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

Dictionaries

- English-Thai dictionary, NECTEC English<–>Thai dictionary; free download with sound files.

- English–Thai Dictionary: English–Thai bilingual online dictionary

- The Royal Institute Dictionary, official standard Thai–Thai dictionary

- Longdo Thai Dictionary LongdoDict

- Thai-English dictionary

- Thai2english.com: LEXiTRON-based Thai–English dictionary

Learners' resources

- thai-language.com English speakers' online resource for the Thai language

- Say Hello in the Thai Language

- Thai Language Wiki (Online lectures)

- Spoken Thai (30 exercises with audio)

- Thai books+Audio, a lot of books in Thai with audio.

- USA Foreign Service Institute (FSI) Thai basic course

Kra Kam–Sui Hlai Ong Be Tai Northern and Central Southwestern Northwestern Lao-Phutai Chiang Saen Categories:- Thai language

- Isolating languages

- Languages of Thailand

- Tai languages

- SVO languages

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.