- Devarim (parsha)

-

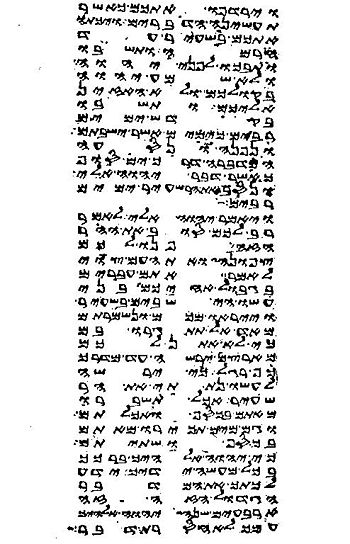

Devarim, D’varim, or Debarim (דְּבָרִים — Hebrew for “words,” the second word, and the first distinctive word, in the parshah) is the 44th weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the first in the book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 1:1–3:22. Jews in the Diaspora generally read it in July or August. It is always read on Shabbat Chazon, the Sabbath directly before Tisha B'Av.

Contents

Summary

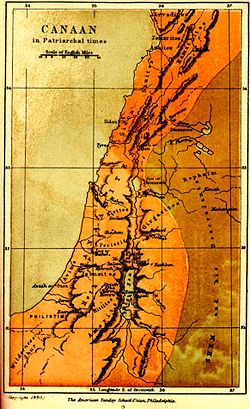

In the 40th year after the Exodus from Egypt, Moses addressed the Israelites on the east side of the Jordan River, recounting the instructions that God had given them. (Deuteronomy 1:1–3.) When the Israelites were at Horeb — Mount Sinai — God told them that they had stayed long enough at that mountain, and it was time for them to make their way to the hill country of Canaan and take possession of the land that God swore to assign to their fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and their heirs after them. (Deuteronomy 1:6–8.)

Moses appointed the chiefs

Then Moses told the Israelites that he could not bear the burden of their bickering alone, and thus directed them to pick leaders from each tribe who were wise, discerning, and experienced. (Deuteronomy 1:9–13.) They did, and Moses appointed the leaders as chiefs of thousands, chiefs of hundreds, chiefs of fifties, and chiefs of tens. (Deuteronomy 1:14–15.) Moses charged the magistrates to hear and decide disputes justly, treating alike Israelite and stranger, low and high. (Deuteronomy 1:16–17.) Moses directed them to bring him any matter that was too difficult to decide. (Deuteronomy 1:17.)

The scouts

The Israelites set out from Horeb to Kadesh-barnea, and Moses told them that God had placed the land at their disposal and that they should not fear, but take the land. (Deuteronomy 1:19–21.) The Israelites asked Moses to send men ahead to reconnoiter the land, and he approved the plan, selecting 12 men, one from each tribe. (Deuteronomy 1:22–24.) The scouts came to the wadi Eshcol, retrieved some of the fruit of the land, and reported that it was a good land. (Deuteronomy 1:24–25.) But the Israelites flouted God’s command and refused to go into the land, instead sulking in their tents about reports of people stronger and taller than they and large cities with sky-high walls. (Deuteronomy 1:26–28.) Moses told them not to fear, as God would go before them and would fight for them, just as God did for them in Egypt and the wilderness. (Deuteronomy 1:29–31.) When God heard the Israelites’ loud complaint, God became angry and vowed that not one of the men of that evil generation would see the good land that God swore to their fathers, except Caleb, whom God would give the land on which he set foot, because he remained loyal to God. (Deuteronomy 1:34–36.) Moses complained that because of the people, God was incensed with Moses too, and told him that he would not enter the land either. (Deuteronomy 1:37.) God directed that Moses’s attendant Joshua would enter the land and allot it to Israel. (Deuteronomy 1:38.) And the little ones — whom the Israelites said would be carried off — would also enter and possess the land. (Deuteronomy 1:39.) The Israelites replied that now they would go up and fight, just as God commanded them, but God told Moses to warn them not to, as God would not travel in their midst and they would be routed by their enemies. (Deuteronomy 1:41–42.) Moses told them, but they would not listen, but flouted God’s command and willfully marched into the hill country. (Deuteronomy 1:43.) Then the Amorites who lived in those hills came out like so many bees and crushed the Israelites at Hormah in Seir. (Deuteronomy 1:44.)

Encounters with the Edomites and Ammonites

The Israelites remained at Kadesh a long time, marched back into the wilderness by the way of the Sea of Reeds, and then skirted the hill country of Seir a long time. (Deuteronomy 1:46–2:1.) Then God told Moses that they had been skirting that hill country long enough and should now turn north. (Deuteronomy 2:2–3.) God instructed that the people would be passing through the territory of their kinsmen, the descendants of Esau in Seir, and that the Israelites should be very careful not to provoke them and should purchase what food and water they ate and drank, for God would not give the Israelites any of their land. (Deuteronomy 2:4–6.) So the Israelites moved on, away from their kinsmen the descendants of Esau, and marched on in the direction of the wilderness of Moab. (Deuteronomy 2:8.)

God told Moses not to harass or provoke the Moabites, for God would not give the Israelites any of their land, having assigned it as a possession to the descendants of Lot. (Deuteronomy 2:9.) The Israelites spent 38 years traveling from Kadesh-barnea until they crossed the wadi Zered, and the whole generation of warriors perished from the camp, as God had sworn. (Deuteronomy 2:14–15.) Then God told Moses that the Israelites would be passing close to the Ammonites, but the Israelites should not harass or start a fight with them, for God would not give the Israelites any part of the Ammonites’ land, having assigned it as a possession to the descendants of Lot. (Deuteronomy 2:17–19.)

Og’s bed (engraving circa 1770 by Johann Balthasar Probst)

Og’s bed (engraving circa 1770 by Johann Balthasar Probst)

Conquest of Sihon

God instructed the Israelites to set out across the wadi Arnon, to attack Sihon the Amorite, king of Heshbon, and begin to occupy his land. (Deuteronomy 2:24.) Moses sent messengers to King Sihon with an offer of peace, asking for passage through his country, promising to keep strictly to the highway, turning neither to the right nor the left, and offering to purchase what food and water they would eat and drink. (Deuteronomy 2:26–29.) But King Sihon refused to let the Israelites pass through, because God had stiffened his will and hardened his heart in order to deliver him to the Israelites. (Deuteronomy 2:30.) Sihon and his men took the field against the Israelites at Jahaz, but God delivered him to the Israelites, and the Israelites defeated him, captured all his towns, and doomed every town, leaving no survivor, retaining as booty only the cattle and the spoil. (Deuteronomy 2:32–35.) From Aroer on the edge of the Arnon valley to Gilead, not a city was too mighty for the Israelites; God delivered everything to them. (Deuteronomy 2:36.)

Conquest of Og

The Israelites made their way up the road to Bashan, and King Og of Bashan and his men took the field against them at Edrei, but God told Moses not to fear, as God would deliver Og, his men, and his country to the Israelites to conquer as they had conquered Sihon. (Deuteronomy 3:1–2.) So God delivered King Og of Bashan, his men, and his 60 towns into the Israelites’ hands, and they left no survivor. (Deuteronomy 3:3–7.) Og was so big that his iron bedstead was nine cubits long and four cubits wide. (Deuteronomy 3:11.)

Land for the Tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh

Moses assigned land to the Reubenites, the Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh. (Deuteronomy 3:12–17.) And Moses charged them that even though they had already received their land, they needed to serve as shock-troops at the head of their Israelite kinsmen, leaving only their wives, children, and livestock in the towns that Moses had assigned to them, until God had granted the Israelites their land west of the Jordan. (Deuteronomy 3:18–20.) And Moses charged Joshua not to fear the kingdoms west of the Jordan, for God would battle for him and would do to all those kingdoms just as God had done to Sihon and Og. (Deuteronomy 3:21–22.)

In ancient parallels

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Numbers 13:22 and 28 refer to the “children of Anak” (יְלִדֵי הָעֲנָק, yelidei ha-anak), Numbers 13:33 refers to the “sons of Anak” (בְּנֵי עֲנָק, benei anak), and Deuteronomy 1:28, 2:10–11, 2:21, and 9:2 refer to the “Anakim” (עֲנָקִים). John A. Wilson suggested that the Anakim may be related to the Iy-‘anaq geographic region named in Middle Kingdom Egyptian (19th to 18th century BCE) pottery bowls that had been inscribed with the names of enemies and then shattered as a kind of curse. (Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Edited by James B. Pritchard, 328. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-691-03503-2.)

In inner-biblical interpretation

Deuteronomy chapter 1

Exodus 18:13–26 and Deuteronomy 1:9–18 both tell the story of appointment of judges. Whereas in Deuteronomy 1:9–18, Moses creates the impression that he decided to distribute his duties, Exodus 18:13–24 makes clear that Jethro suggested the idea to Moses and persuaded him of its merit.

Numbers 13:1–14:45 and Deuteronomy 1:19–45 both tell the story of the spies. Whereas Numbers 13:1–2 says that God told Moses to send men to spy out the land of Canaan, in Deuteronomy 1:22–23, Moses recounted that all the Israelites asked him to send men to search the land, and the idea pleased him. Whereas Numbers 13:31–33 reports that the spies spread an evil report that the Israelites were not able to go up against the people of the land for they were stronger and taller than the Israelites, in Deuteronomy 1:25, Moses recalled that the spies brought back word that the land that God gave them was good.

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Both Deuteronomy 2:4–11 and Judges 11:17 report the Israelites’ interaction with Edom and Moab. Judges 11:17 reports that the Israelites sent messengers to the kings of both countries asking for passage through their lands, but both kings declined to let the Israelites pass.

Deuteronomy chapter 3

The blessing of Moses for Gad in Deuteronomy 33:20–21 relates to the role of Gad in taking land east of the Jordan in Numbers 32:1–36 and Deuteronomy 3:16–20. In Deuteronomy 33:20, Moses commended Gad’s fierceness, saying that Gad dwelt as a lioness and tore the arm and the head. Immediately thereafter, in Deuteronomy 33:21, Moses noted that Gad chose a first part of the land for himself.

In classical rabbinic interpretation

Deuteronomy chapter 1

The Mishnah taught that when fulfilling the commandment of Deuteronomy 31:12 to “assemble the people . . . that they may hear . . . all the words of this law,” the king would start reading at Deuteronomy 1:1. (Mishnah Sotah 7:8; Babylonian Talmud Sotah 41a.)

The school of Rabbi Yannai interpreted the place name Di-zahab (דִי זָהָב) in Deuteronomy 1:1 to refer to one of the Israelites’ sins that Moses recounted in the opening of his address. The school of Rabbi Yannai deduced from the word Di-zahab that Moses spoke insolently towards heaven. The school of Rabbi Yannai taught that Moses told God that it was because of the silver and gold (זָהָב, zahav) that God showered on the Israelites until they said “Enough” (דַּי, dai) that the Israelites made the Golden Calf. They said in the school of Rabbi Yannai that a lion does not roar with excitement over a basket of straw but over a basket of meat. Rabbi Oshaia likened it to the case of a man who had a lean but large-limbed cow. The man gave the cow good feed to eat and the cow started kicking him. The man deduced that it was feeding the cow good feed that caused the cow to kick him. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba likened it to the case of a man who had a son and bathed him, anointed him, gave him plenty to eat and drink, hung a purse round his neck, and set him down at the door of a brothel. How could the boy help sinning? Rav Aha the son of Rav Huna said in the name of Rav Sheshet that this bears out the popular saying that a full stomach leads to a bad impulse. As Hosea 13:6 says, “When they were fed they became full, they were filled and their heart was exalted; therefore they have forgotten Me.” (Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 32a; see also Babylonian Talmud Yoma 86b.)

Interpreting Deuteronomy 1:15, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that since the nation numbered about 600,000 men, the chiefs of thousands amounted to 600; those of hundreds, 6,000; those of fifties, 12,000; and those of tens, 60,000. Hence they taught that the number of officers in Israel totaled 78,600. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 18a.)

Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words “And I charged your judges at that time” in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach that judges were to resort to the rod and the lash with caution. Rabbi Haninah interpreted the words “hear the causes between your brethren, and judge righteously” in Deuteronomy 1:16 to warn judges not to listen to the claims of litigants in the absence of their opponents, and to warn litigants not to argue their cases to the judge before their opponents have appeared. Resh Lakish interpreted the words “judge righteously” in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach judges to consider all the aspects of the case before deciding. Rabbi Judah interpreted the words “between your brethren” in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach judges to make a scrupulous division of liability between the lower and the upper parts of a house, and Rabbi Judah interpreted the words “and the stranger that is with him” in Deuteronomy 1:16 to teach judges to make a scrupulous division of liability even between a stove and an oven. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 7b.)

Rabbi Judah interpreted the words “you shall not respect persons in judgment” in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach judges not to favor their friends, and Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words to teach judges not to treat a litigant as a stranger, even if the litigant was the judge’s enemy. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 7b.)

Resh Lakish interpreted the words “you shall hear the small and the great alike” in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach that a judge must treat a lawsuit involving the smallest coin in circulation (“a mere perutah”) as of the same importance as one involving 2 million times the value (“a hundred mina”). And the Gemara deduced from this rule that a judge must hear cases in the order that they were brought, even if a case involving a lesser value was brought first. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a.)

Resh Lakish (or others say Rabbi Judah ben Lakish or Rabbi Joshua ben Lakish) read the words “you shall not be afraid of the face of any man” in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach that once a judge has heard a case and knows in whose favor judgment inclines, the judge cannot withdraw from the case, even if the judge must rule against the more powerful litigant. But before a judge has heard a case, or even after so long as the judge does not yet know in whose favor judgment inclines, the judge may withdraw from the case to avoid having to rule against the more powerful litigant and suffer harassment from that litigant. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 6b.) And Rabbi Hanan read the words “you shall not be afraid of . . . any man” in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach judges not to withhold any arguments out of deference to the powerful. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a.)

Rabbi Eliezer the son of Rabbi Jose the Galilean deduced from the words “the judgment is God's” in Deuteronomy 1:17 that once litigants have brought a case to court, a judge must not arbitrate a settlement, for a judge who arbitrates sins by deviating from the requirements of God’s Torah; rather, the judge must “let the law cut through the mountain” (and thus even the most difficult case). (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 6b.)

Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Haninah read the words “the judgment is God's” in Deuteronomy 1:17 to teach that God views the action of wicked judges unjustly taking money away from one and giving it to another as an imposition upon God, putting God to the trouble of returning the value to the rightful owner. (Rashi interpreted that it was though the judge had taken the money from God.) (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a.)

Rabbi Haninah (or some say Rabbi Josiah) taught that Moses was punished for his arrogance when he told the judges in Deuteronomy 1:17: “the cause that is too hard for you, you shall bring to me, and I will hear it.” Rabbi Haninah said that Numbers 27:5 reports Moses’s punishment, when Moses found himself unable to decide the case of the daughters of Zelophehad. Rav Nahman objected to Rabbi Haninah’s interpretation, noting that Moses did not say that he would always have the answers, but merely that he would rule if he knew the answer or seek instruction if he did not. Rav Nahman cited a Baraita to explain the case of the daughters of Zelophehad: God had intended that Moses write the laws of inheritance, but found the daughters of Zelophehad worthy to have the section recorded on their account. (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a.)

Rabbi Eleazar, on the authority of Rabbi Simlai, noted that Deuteronomy 1:16 says, “And I charged your judges at that time,” while Deuteronomy 1:18 similarly says, “I charged you [the Israelites] at that time.” Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Deuteronomy 1:18 meant to warn the Congregation to revere their judges, and Deuteronomy 1:16 meant to warn the judges to be patient with the Congregation. Rabbi Hanan (or some say Rabbi Shabatai) said that this meant that judges must be as patient as Moses, who Numbers 11:12 reports acted “as the nursing father carries the sucking child.” (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a.)

Resh Lakish interpreted the words “Send you” in Numbers 13:2 to indicate that God gave Moses discretion whether or not to send the spies. Resh Lakish read Moses’ recollection of the matter in Deuteronomy 1:23 that “the thing pleased me well” to mean that sending the spies pleased Moses well but not God. (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 34b.)

Rabbi Ammi cited the spies’ statement in Deuteronomy 1:28 that the Canaanite cities were “great and fortified up to heaven” to show that the Torah sometimes exaggerated. (Babylonian Talmud Chullin 90b, Tamid 29a.)

The Mishnah taught that it was on Tisha B'Av (just before which Jews read parshah Devarim) that God issued the decree reported in Deuteronomy 1:35–36 that the generation of the spies would not enter the Promised Land. (Mishnah Taanit 4:6; Babylonian Talmud Taanit 26b, 29a.)

Noting that in the incident of the spies, God did not punish those below the age of 20 (see Numbers 14:29), whom Deuteronomy 1:39 described as “children that . . . have no knowledge of good or evil,” Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani taught in Rabbi Jonathan’s name that God does not punish people for the actions that they take in their first 20 years. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 89b.)

Deuteronomy chapter 2

Interpreting the words “You have circled this mountain (הָר, har) long enough” in Deuteronomy 2:3, Rabbi Haninah taught that Esau paid great attention to his parent (horo), his father, whom he supplied with meals, as Genesis 25:28 reports, “Isaac loved Esau, because he ate of his venison.” Rabbi Samuel the son of Rabbi Gedaliah concluded that God decided to reward Esau for this. When Jacob offered Esau gifts, Esau answered Jacob in Genesis 33:9, “I have enough (רָב, rav); do not trouble yourself.” So God declared that with the same expression that Esau thus paid respect to Jacob, God would command Jacob’s descendants not to trouble Esau’s descendants, and thus God told the Israelites, “You have circled . . . long enough (רַב, rav).” (Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:17.)

Rav Hiyya bar Abin said in Rabbi Johanan's name that the words, “I have given Mount Seir to Esau for an inheritance,” in Deuteronomy 2:5 establish that even idolaters inherit from their parents under Biblical law. The Gemara reported a challenge that perhaps Esau inherited because he was an apostate Jew. Rav Hiyya bar Abin thus argued that the words, “I have given Ar to the children of Lot as a heritage,” in Deuteronomy 2:9 establish gentiles’ right to inherit. (Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 18a.)

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba, citing Rabbi Johanan, taught that God rewards even polite speech. In Genesis 19:37, Lot’s older daughter named her son Moab (“of my father”), and so in Deuteronomy 2:9, God told Moses, “Be not at enmity with Moab, neither contend with them in battle”; God forbade only war with the Moabites, but the Israelites might harass them. In Genesis 19:38, in contrast, Lot’s younger daughter named her son Ben-Ammi (the less shameful “son of my people”), and so in Deuteronomy 2:19, God told Moses, “Harass them not, nor contend with them”; the Israelites were not to harass the Ammonites at all. (Babylonian Talmud Nazir 23b.)

Even though in Deuteronomy 2:9 and 2:19, God forbade the Israelites from occupying the territory of Ammon and Moab, Rav Papa taught that the land of Ammon and Moab that Sihon conquered (as reported in Numbers 21:26) became purified for acquisition by the Israelites through Sihon’s occupation of it (as discussed in Judges 11:13–23). (Babylonian Talmud Gittin 38a.)

Explaining why Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel said (in Mishnah Taanit 4:8; Babylonian Talmud Taanit 26b) that there never were in Israel more joyous days than Tu B'Av (the fifteenth of Av) and Yom Kippur, Rabbah bar bar Hanah said in the name of Rabbi Johanan (or others say Rav Dimi bar Joseph said in the name of Rav Nahman) that Tu B'Av was the day on which the generation of the wilderness stopped dying out. For a Master deduced from the words, “So it came to pass, when all the men of war were consumed and dead . . . that the Lord spoke to me,” in Deuteronomy 2:16–17 that as long as the generation of the wilderness continued to die out, God did not communicate with Moses, and only thereafter — on Tu B'Av — did God resume that communication. (Babylonian Talmud Taanit 30b, Bava Batra 121a–b.)

A Baraita deduced from Deuteronomy 2:25 that just as the sun stood still for Joshua in Joshua 10:13, so the sun stood still for Moses, as well. The Gemara (some say Rabbi Eleazar) explained that the identical circumstances could be derived from the use of the identical expression “I will begin” in Deuteronomy 2:25 and in Joshua 3:7. Rabbi Johanan (or some say Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani) taught that this conclusion could be derived from the use of the identical word “put” (tet) in Deuteronomy 2:25 and Joshua 10:11. And Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani (or some say Rabbi Johanan) taught that this conclusion could be deduced from the words “the peoples that are under the whole heaven, who, when they hear the report of you, shall tremble, and be in anguish because of you” in Deuteronomy 2:25. Rabbi Samuel (or some say Rabbi Johanan) taught that the peoples trembled and were in anguish because of Moses when the sun stood still for him. (Babylonian Talmud Avodah Zarah 25a, Taanit 20a.)

A midrash interpreted the Israelites’ encounter with Sihon in Numbers 21:21–31 and Deuteronomy 2:24–3:10. Noting the report of Numbers 21:21–22 that “Israel sent messengers to Sihon king of the Amorites, saying: ‘Let me pass through your land,’” the midrash taught that the Israelites sent messengers to Sihon just as they had to Edom to inform the Edomites that the Israelites would not cause Edom any damage. Noting the report of Deuteronomy 2:28 that the Israelites offered Sihon, “You shall sell me food for money . . . and give me water for money,” the midrash noted that water is generally given away for free, but the Israelites offered to pay for it. The midrash noted that in Numbers 21:21, the Israelites offered, “We will go by the king's highway,” but in Deuteronomy 2:29, the Israelites admitted that they would go “until [they] shall pass over the Jordan,” thus admitting that they were going to conquer Canaan. The midrash compared the matter to a watchman who received wages to watch a vineyard, and to whom a visitor came and asked the watchman to go away so that the visitor could cut off the grapes from the vineyard. The watchman replied that the sole reason that the watchman stood guard was because of the visitor. The midrash explained that the same was true of Sihon, as all the kings of Canaan paid Sihon money from their taxes, since Sihon appointed them as kings. The midrash interpreted Psalm 135:11, which says, “Sihon king of the Amorites, and Og king of Bashan, and all the kingdoms of Canaan,” to teach that Sihon and Og were the equal of all the other kings of Canaan. So the Israelites asked Sihon to let them pass through Sihon’s land to conquer the kings of Canaan, and Sihon replied that the sole reason that he was there was to protect the kings of Canaan from the Israelites. Interpreting the words of Numbers 21:23, “and Sihon would not suffer Israel to pass through his border; but Sihon gathered all his people together,” the midrash taught that God brought this about designedly so as to deliver Sihon into the Israelites’ hands without trouble. The midrash interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 3:2, “Sihon king of the Amorites, who dwelt at Heshbon,” to say that if Heshbon had been full of mosquitoes, no person could have conquered it, and if Sihon had been living in a plain, no person could have prevailed over him. The midrash taught that Sihon thus would have been invincible, as he was powerful and dwelt in a fortified city. Interpreting the words, “Who dwelt at Heshbon,” the midrash taught that had Sihon and his armies remained in different towns, the Israelites would have worn themselves out conquering them all. But God assembled them in one place to deliver them into the Israelites’ hands without trouble. In the same vein, in Deuteronomy 2:31 God said, “Behold, I have begun to deliver up Sihon . . . before you,” and Numbers 21:23 says, “Sihon gathered all his people together,” and Numbers 21:23 reports, “And Israel took all these cities.” (Numbers Rabbah 19:29.)

Deuteronomy chapter 3

A midrash taught that according to some authorities, Israel fought Sihon in the month of Elul, celebrated the Festival in Tishri, and after the Festival fought Og. The midrash inferred this from the similarity of the expression in Deuteronomy 16:7, “And you shall turn in the morning, and go to your tents,” which speaks of an act that was to follow the celebration of a Festival, and the expression in Numbers 21:3, “and Og the king of Bashan went out against them, he and all his people.” The midrash inferred that God assembled the Amorites to deliver them into the Israelites’ hands, as Numbers 21:34 says, “and the Lord said to Moses: ‘Fear him not; for I have delivered him into your hand.” The midrash taught that Moses was afraid, as he thought that perhaps the Israelites had committed a trespass in the war against Sihon, or had soiled themselves by the commission of some transgression. God reassured Moses that he need not fear, for the Israelites had shown themselves perfectly righteous. The midrash taught that there was not a mighty man in the world more difficult to overcome than Og, as Deuteronomy 3:11 says, “only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim.” The midrash told that Og had been the only survivor of the strong men whom Amraphel and his colleagues had slain, as may be inferred from Genesis 14:5, which reports that Amraphel “smote the Rephaim in Ashteroth-karnaim,” and one may read Deuteronomy 3:1 to indicate that Og lived near Ashteroth. The midrash taught that Og was the refuse among the Rephaim, like a hard olive that escapes being mashed in the olive press. The midrash inferred this from Genesis 14:13, which reports that “there came one who had escaped, and told Abram the Hebrew,” and the midrash indentified the man who had escaped as Og, as Deuteronomy 3:11 describes him as a remnant, saying, “only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim.” The midrash taught that Og intended that Abram should go out and be killed. God rewarded Og for delivering the message by allowing him to live all the years from Abraham to Moses, but God collected Og’s debt to God for his evil intention toward Abraham by causing Og to fall by the hand of Abraham’s descendants. On coming to make war with Og, Moses was afraid, thinking that he was only 120 years old, while Og was more than 500 years old, and if Og had not possessed some merit, he would not have lived all those years. So God told Moses (in the words of Numbers 21:34), “fear him not; for I have delivered him into your land,” implying that Moses should slay Og with his own hand. The midrash noted that in Deuteronomy 3:2, God told Moses to “do to him as you did to Sihon,” and Deuteronomy 3:6 reports that the Israelites “utterly destroyed them,” but Deuteronomy 3:7 reports, “All the cattle, and the spoil of the cities, we took for a prey to ourselves.” The midrash concluded that the Israelites utterly destroyed the people so as not to derive any benefit from them. (Numbers Rabbah 19:32.)

Rabbi Phinehas ben Yair taught that the 60 rams, 60 goats, and 60 lambs that Numbers 7:88 reports that the Israelites sacrificed as a dedication-offering of the altar symbolized (among other things) the 60 cities of the region of Argob that Deuteronomy 3:4 reports that the Israelites conquered. (Numbers Rabbah 16:18.)

Abba Saul (or some say Rabbi Johanan) told that once when pursuing a deer, he entered a giant thighbone of a corpse and pursued the deer for three parasangs but reached neither the deer nor the end of the thighbone. When he returned, he was told that it was the thighbone of Og, King of Bashan, of whose extraordinary height Deuteronomy 3:11 reports. (Babylonian Talmud Nidah 24b.)

A midrash deduced from the words in Deuteronomy 3:11, “only Og king of Bashan remained . . . behold, his bedstead . . . is it not in Rabbah of the children of Ammon?” that Og had taken all the land of the children of Ammon. Thus there was no injustice when Israel came and took the land away from Og. (Numbers Rabbah 20:3.)

Noting that Deuteronomy 3:21 and 3:23 both use the same expression “at that time” (בָּעֵת הַהִוא), a midrash deduced that the events of the two verses took place at the same time. Thus Rav Huna taught that as soon as God told Moses to hand over his office to Joshua, Moses immediately began to pray to be permitted to enter the Promised Land. The midrash compared Moses to a governor who could be sure that the king would confirm whatever orders he gave so long as he retained his office. The governor redeemed whomever he desired and imprisoned whomever he desired. But as soon as the governor retired and another was appointed in his place, the gatekeeper would not let him enter the king’s palace. Similarly, as long as Moses remained in office, he imprisoned whomever he desired and released whomever he desired, but when he was relieved of his office and Joshua was appointed in his stead, and he asked to be permitted to enter the Promised Land, God in Deuteronomy 3:26 denied his request. (Deuteronomy Rabbah 2:5.)

Commandments

According to Maimonides

Maimonides cited verses in the parshah for three negative commandments:

- That the judge not be afraid of a bad person when judging (Deuteronomy 1:17.)

- Not to appoint as judge one who is not learned in the laws of the Torah, even if the person is learned in other disciplines (Deuteronomy 1:17.)

- That warriors shall not fear their enemies nor be frightened of them in battle (Deuteronomy 3:22.)

(Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Negative Commandments 58, 276, 284. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 2:55–56, 259, 265–66. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4.)

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are two negative commandments in the parshah.

- Not to appoint any judge who is unlearned in the Torah, even if the person is generally learned (Deuteronomy 1:17.)

- That a judge presiding at a trial should not fear any evil person (Deuteronomy 1:17.)

(Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 4:238–45. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1988. ISBN 0-87306-457-7.)

Haftarah

Devarim is always read on the final Shabbat of Admonition, the Shabbat immediately prior to Tisha B'Av. That Shabbat is called Shabbat Chazon, corresponding to the first word of the haftarah, which is Isaiah 1:1–27. Many communities chant the majority of this haftarah in the mournful melody of the Book of Lamentations due to the damning nature of the vision as well as its proximity to the saddest day of the Hebrew calendar, the holiday on which Lamentations is chanted.

In the liturgy

Some Jews recite the blessing of fruitfulness in Deuteronomy 1:10–11 among the verses of blessing recited at the conclusion of the Sabbath. (Menachem Davis. The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation, 643. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-697-3.)

“Mount Lebanon . . . Siryon,” another name for Mount Hermon, as Deuteronomy 3:9 explains, is reflected in Psalm 29:6, which is in turn one of the six Psalms recited at the beginning of the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service . (Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, 20. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8.)

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parshah. For parshah Devarim, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Hijaz, the maqam that expresses mourning and sadness. This maqam is appropriate not due to the content of the parshah, but because this is the parshah that falls on the Shabbat prior to Tisha B'Av, the date that marks the destruction of the Temples.

Further reading

The parshah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Genesis 14:5–6 (Rephaim, Emim, Horites); 15:5 (numerous as stars); 22:17 (numerous as stars); 26:4 (numerous as stars).

- Exodus 4:21; 7:3; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8 (hardening of heart); 18:13–26 (appointment of the chiefs); 32:34 (command to lead the people to the Promised Land).

- Numbers 10:11–34 (departure for the Promised Land); 13:1–14:45 (the spies); 20:14–21; 21:21–35 (victories over Sihon and Og); 27:18–23; 32:1–33.

- Deuteronomy 9:23.

- Joshua 1:6–9, 12–18; 11:20 (hardening of heart); 13:8–32.

Early nonrabbinic

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:14:1–2; 3:15:1–3; 4:1:1–3; 4:4:5; 4:5:1–3.

- Romans 9:14–18. 1st Century. (hardening of heart).

- Revelation 17:17. Late 1st Century. (changing hearts to God’s purpose).

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Taanit 4:6; Sotah 7:8. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 315, 459. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Sukkah 3:13; Sotah 4:6, 7:12, 17, 14:4; Menachot 7:8; Arakhin 5:16. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifre to Deuteronomy 1:1–25:6. Land of Israel, circa 250–350 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifre to Deuteronomy: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 1:15–65. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987. ISBN 1-55540-145-7.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Sheviit 47a; Maasrot 4b; Challah 45a; Bikkurim 12a. Land of Israel, circa 400 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, vols. 6b, 9, 11, 12. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006–2009.

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 32a; Shabbat 85a; Eruvin 30a, 100b; Yoma 86b; Rosh Hashanah 2b, 28b; Taanit 20a, 30b; Megillah 2b, 10a; Moed Katan 15b; Chagigah 6b; Yevamot 47a, 86b; Nedarim 20b; Nazir 23b, 61a; Sotah 34b, 35b, 47b, 48b; Gittin 38a; Kiddushin 18a; Bava Kamma 38a–b; Bava Batra 121b; Sanhedrin 6b, 7b–8a, 17a, 102a; Shevuot 16a, 47b; Avodah Zarah 25a, 37b; Horayot 10b; Zevachim 115b; Menachot 65a; Chullin 60b, 90b; Arakhin 16b, 32b, 33b; Tamid 29a; Niddah 24b. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:1–25. Land of Israel, 9th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, 7: 1–28. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Rashi. Commentary. Deuteronomy 1–3. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 5:1–44. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-030-7.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 2:14. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Intro. by Henry Slonimsky, 91. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

- Benjamin of Tudela. The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela. Spain, 1173. Reprinted in The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela: Travels in the Middle Ages. Introductions by Michael A. Singer, Marcus Nathan Adler, A. Asher, 91. Malibu, Calif.: Joseph Simon, 1983. ISBN 0-934710-07-4. (giants).

- Zohar 1:178a; 2:31a, 68b, 183b, 201a, 214a; 3:117b, 190a, 260b, 284a, 286b. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

Modern

- Samson Raphael Hirsch. Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, 265–67. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 ISBN 0-900689-40-4. Originally published as Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel’s Pflichten in der Zerstreuung. Germany, 1837.

- Martin Buber. On the Bible: Eighteen studies, 80–92. New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

- Alan R. Millard. “Kings Og’s Iron Bed: Fact or fancy?” Bible Review 6 (2) (Apr. 1990).

- Moshe Weinfeld. Deuteronomy 1-11, 5:125–89. New York: Anchor Bible, 1991. ISBN 0-385-17593-0.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. The JPS Torah Commentary: Deuteronomy: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, 3–38, 422–30. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996. ISBN 0-8276-0330-4.

- Elie Kaplan Spitz. “On the Use of Birth Surrogates.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1997. EH 1:3.1997b. Reprinted in Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, 529, 535–36. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. ISBN 0-916219-19-4. (that Jews will become as numerous as “the stars of heaven” requires human help).

- Alan Lew. This Is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation, 38–45, 51–52. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 2003. ISBN 0-316-73908-1.

- Suzanne A. Brody. “Travelogue.” In Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems, 102. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. ISBN 1-60047-112-9.

External links

Texts

Commentaries

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- Aish.com

- American Jewish University

- Anshe Emes Synagogue, Los Angeles

- Bar-Ilan University

- Chabad.org

- eparsha.com

- G-dcast

- The Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash

- Jewish Agency for Israel

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- Miriam Aflalo

- MyJewishLearning.com

- Ohr Sameach

- Orthodox Union

- OzTorah, Torah from Australia

- Oz Ve Shalom — Netivot Shalom

- Pardes from Jerusalem

- RabbiShimon.com

- Rabbi Shlomo Riskin

- Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld

- Reconstructionist Judaism

- Sephardic Institute

- Shiur.com

- 613.org Jewish Torah Audio

- Tanach Study Center

- Teach613.org, Torah Education at Cherry Hill

- Torah from Dixie

- Torah.org

- TorahVort.com

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

- What’s Bothering Rashi?

- Yeshiva University

- Yeshivat Chovevei Torah

Weekly Torah Portions Genesis Bereishit · Noach · Lech-Lecha · Vayeira · Chayei Sarah · Toledot · Vayetze · Vayishlach · Vayeshev · Miketz · Vayigash · Vayechi

Exodus Leviticus Numbers Deuteronomy Devarim · Va'etchanan · Eikev · Re'eh · Shoftim · Ki Teitzei · Ki Tavo · Nitzavim · Vayelech · Haazinu · V'Zot HaBerachahCategories:- Weekly Torah readings

- Book of Deuteronomy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.