- Chadian–Libyan conflict

-

Chadian-Libyan conflict

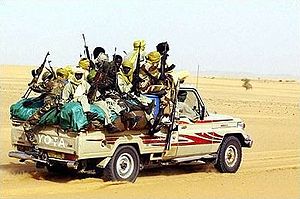

Chadian soldiers in a Toyota pickup modified into a technicalDate 1978–1987 Location Chad Result Chadian victory Territorial

changesChad gains control of the Aouzou Strip Belligerents  Libya

Libya

Chad

Chad

France

France

Aided by:

United States[2]

United States[2]

Egypt[1]

Egypt[1]

Sudan[3]

Sudan[3]Commanders and leaders  Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Gaddafi

Massoud Abdelhafid

Massoud Abdelhafid Hissène Habré

Hissène Habré

Hassan Djamous

Hassan Djamous

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (1974-1981)

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (1974-1981)

François Mitterrand (1981-1988)

François Mitterrand (1981-1988)Casualties and losses 7,500+ killed

1,000+ captured

800+ Armored vehicles

28+ Aircraft1,000+ killed Chad received aid from France and Zaire, while Libya was backed by the GUNT Chadian-Libyan conflictThe Chadian–Libyan conflict was a state of sporadic warfare events in Chad between 1978 and 1987 between Libyan and Chadian forces. Libya had been involved in Chad's internal affairs prior to 1978 and before Muammar Gaddafi's rise to power in Libya in 1969, beginning with the extension of the Chadian Civil War to northern Chad in 1968.[4] The conflict was marked by a series of four separate Libyan interventions in Chad, taking place in 1978, 1979, 1980–1981 and 1983–1987. In all of these occasions Gaddafi had the support of a number of factions participating in the civil war, while Libya's opponents found the support of the French government, which intervened militarily to save the Chadian government in 1978, 1983 and 1986.

The military pattern of the war delineated itself in 1978, with the Libyans providing armour, artillery and air support and their Chadian allies the infantry, that assumed the bulk of the scouting and fighting.[5] This pattern was radically changed in 1986, towards the end of the war, when all Chadian forces united in opposing the Libyan occupation of northern Chad with a degree of unity that had never been seen before in Chad.[6] This deprived the Libyan forces of their habitual infantry, exactly when they found themselves confronting a mobile army, well provided now with anti-tank and anti-air missiles, thus cancelling the Libyan superiority in fire-power. What followed was the Toyota War, in which the Libyan forces were routed and expelled from Chad, putting an end to the conflict.

Regarding the reasons behind Gaddafi's involvement with Chad, the initial reason stood in his ambition to annex the Aouzou Strip, the northernmost part of Chad that he claimed as part of Libya on the grounds of an unratified treaty of the colonial period.[4] In 1972 his goals became, in the evaluation of historian Mario Azevedo, the creation of a client state in Libya's "underbelly", an Islamic republic modelled after his jamahiriya, that would maintain close ties with Libya, and secure his control over the Aouzou Strip; expulsion of the French from the region, and use of Chad as a base to expand his influence in Central Africa.[7]

Events

Occupation of the Aouzou Strip

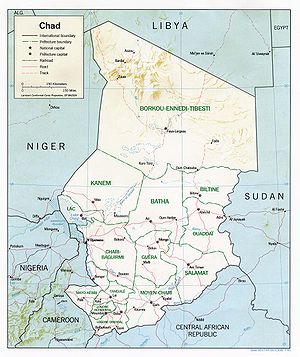

Libyan involvement with Chad can be said to have started in 1968, during the Chadian Civil War, when the insurgent Muslim National Liberation Front of Chad (FROLINAT) extended its guerrilla war against the Christian President François Tombalbaye to the northerly Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Prefecture (BET).[8] Libya's king Idris I felt compelled to support the FROLINAT because of long-standing strong links between the two sides of the Chadian-Libyan border. To preserve relations with Chad's former colonial master and current protector, France, Idris limited himself to granting the rebels sanctuary in Libyan territory and to providing only non-lethal supplies.[4]

All this changed with the Libyan coup d'état of 1 September 1969 that deposed Idris and brought Muammar Gaddafi to power. Gaddafi claimed the Aouzou Strip in northern Chad, referring to an unratified treaty signed in 1935 by Italy and France, (then the colonial powers of Libya and Chad, respectively).[4] Such claims had been previously made when in 1954 Idris had tried to occupy Aouzou, but his troops were repelled by the French Colonial Forces.[9]

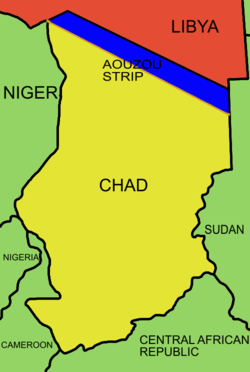

The Aouzou Strip, highlighted in blue.

Though initially wary of the FROLINAT, Gaddafi had come to see by 1970 the organization as useful to his needs and with the support of Soviet bloc nations, particularly East Germany, trained and armed the insurgents, and provided them with weapons and funding.[4][10] On August 27, 1971 Chad accused Egypt and Libya of backing a coup against then president Tombalbaye by recently amnestied Chadians.[11]

On the same day of the failed coup, Tombalbaye cut all diplomatic relations with Libya and Egypt, and invited all Libyan opposition groups to base themselves in Chad, and started laying claims to Fezzan on the grounds of "historical rights". Gaddafi's answer was to officially recognize on 17 September the FROLINAT as the sole legitimate government of Chad, while in October the Chadian Foreign Minister Baba Hassan denounced at the United Nations Libya's "expansionist ideas".[12]

Through French pressure on Libya, and with Hamani Diori the President of Niger playing the role of mediator, the two countries resumed diplomatic relations on 17 April 1972. Shortly after, Tombalbaye broke diplomatic relations with Israel and is said to have secretly accepted on 28 November to cede the Aouzou Strip to Libya; in exchange Gaddafi pledged 40 million pounds to the Chadian President[13] and the two countries signed in December a Treaty of Friendship. Gaddafi withdrew official support to the FROLINAT and forced its leader Abba Siddick to move his headquarters from Tripoli to Algiers.[14][15] Good relations were confirmed in the following years, with Gaddafi visiting the Chadian capital N'Djamena in March 1974,[16] and in the same month a joint bank was created to provide Chad with investment funds.[12]

Six months after the signature of the 1972 treaty, Libyan troops moved into the Strip and established just north of Aouzou an airbase protected by surface-to-air missiles. A civil administration was set up, attached to Kufra, and Libyan citizenship was extended to the few thousand inhabitants of the area. From that moment, Libyan maps represented the area as part of Libya.[15]

The exact terms by which Libya gained Aouzou remain partly obscure, and are debated. The existence of a secret agreement between Tombalbaye and Gaddafi was revealed only in 1988, when the Libyan President exhibited an alleged copy of a letter in which Tombalbaye recognizes Libyan claims. Against this, scholars like Bernard Lanne have argued that there never was any sort of formal agreement, and that simply Tombalbaye had found expedient for himself not to make mention of the occupation of a part of his country. Also, Libya was unable to exhibit the original copy of the agreement when the case of the Aouzou Strip was brought in 1993 before the International Court of Justice.[15][17]

Expansion of the insurgency

The rapproachment was not to last long, as on 13 April, 1975 a coup d'état removed Tombalbaye and replaced him with General Felix Malloum. As opposition to Tombalbaye's policy of appeasement towards Libya was among the reasons behind the coup, Gaddafi felt the coup as a menace to his influence in Chad and resumed supplying the FROLINAT.[4]

In April 1976, there was a Gaddafi-backed attempted assassination of Malloum,[14] and in the same year Libyan troops started making forays into central Chad in company of FROLINAT forces.[5]

Libyan activism began generating concerns in the strongest faction into which the FROLINAT had split, the Command Council of the Armed Forces of the North (CCFAN). On the issue of the interested nature of Libyan support the insurgents split in October 1976, with a minority leaving the militia and forming the Armed Forces of the North (FAN), led by the anti-Libyan Hissène Habré, while the majority, willing to accept an alliance with Gaddafi, was commanded by Goukouni Oueddei. The latter group was to shortly after rename itself People's Armed Forces (FAP).[18]

In those years, Gaddafi's support had been mostly moral, with only a limited supply of weapons. All this started changing in February 1977, when the Libyans provided Goukouni's men with hundreds of AK-47 assault rifles, dozens of bazookas, 81 and 82mm mortars and recoilless cannons. Armed with these weapons, the FAP attacked in June the Chadian Armed Forces' (FAT) strongholds of Bardaï and Zouar in Tibesti and of Ounianga Kebir in Borkou. Goukouni assumed with this attack full control of the Tibesti, because Bardaï, besieged since 22 June, surrendered on 4 July, while Zouar was evacuated. The FAT lost 300 men, and piles of military supplies fell into the hands of the rebels.[19][20] Ounianga was attacked on June 20, but was saved for the time being by the French military advisors present there.[21]

This year, as it had become evident that the Aouzou Strip was being used by Libya as a base for deeper involvement in Chad, Malloum decided to bring the issue of the Strip's occupation before the United Nations and the Organisation of African Unity.[22] Malloum also decided he needed new allies; because of this, he negotiated a formal alliance with Habré, the Khartoum Accord, in September. This accord was kept secret until 22 January, when a Fundamental Charter was signed, following which a National Union Government was formed on 29 August 1978 with Habré as Prime Minister.[23][24] The Malloum-Habré accord was actively promoted by Sudan and Saudi Arabia, both of which feared a radical Chad controlled by Gaddafi and saw in Habré, with his good Muslim and anti-colonialialist credentials, the only chance to thwart Gaddafi's plans.[25]

Libyan escalation

The Malloum-Habré accord was perceived by Gaddafi as a serious threat to his influence in Chad, and he increased the level of Libyan involvement. For the first time with the active participation of Libyan ground units,[5] Goukouni's FAP unleashed on 29 January 1978 the Ibrahim Abatcha offensive against the last outposts held by the government in northern Chad, namely Faya-Largeau, Fada and Ounianga Kebir. The attacks were successful, and Goukouni and the Libyans assumed control of the BET Prefecture.[26][27]

The decisive confrontation between the Libyan-FAP forces and the Chadian regular forces took place at Faya-Largeau, the capital of the BET. The city, defended by 5,000 Chadian soldiers, fell on 18 February after sharp fighting to 2,500 rebels, supported by possibly as many as 4,000 Libyan troops. The Libyans do not seem to have directly participated in the fighting; in a pattern that was to repeat itself in the future, the Libyans provided armor, artillery and air support.[5] The rebels also were much better armed than before, displaying Strela 2 surface-to-air missiles.[28]

Goukouni had made about 2,500 prisoners with these successes and those in 1977; as a result, the Chadian Armed Forces had lost at least 20% of its manpower,[27] and in particular the Nomad and National Guard (GNN) was decimated by the fall of Fada and Faya.[29] Goukouni used these victories to strengthen his position in the FROLINAT: during a Libyan-sponsored congress held in March in Faya, the insurgency's main factions reunited themselves and nominated Goukouni new secretary-general of the FROLINAT.[30]

Malloum's reaction to the Goukouni–Gaddafi offensive was to sever diplomatic relations with Libya on 6 February and bring before the United Nations Security Council the issue of Libyan involvement in the fighting, as well as raising again the question of Libya's occupation of the Aouzou Strip; but on 19 February, after the fall of Faya, Malloum was forced to accept a ceasefire and withdraw the protest. The ceasefire was reached also because Libya had halted the advance of Goukouni, because of pressure from France, then an important weapon supplier of the Arab country.[26]

Malloum and Gaddafi restored diplomatic relations on 24 February at Sabha in Libya, where an international peace conference was held which included as mediators Niger's President Seyni Kountché and Sudan's Vice-President. Under severe pressure from France, Sudan and Zaire,[31] Malloum was forced to sign on March 27 the Benghazi Accord, which recognized the FROLINAT and agreed on a new ceasefire. Among the chief conditions of the agreement was creation of a joint Libya–Niger military committee, that was tasked with implementing the agreement; through this committee, Chad legitimized Libyan intervention in its territory. The accord also contained another condition dear to Libya, as it asked for the termination of all French military presence in Chad.[26] The stillborn accord was for Gaddafi nothing more than a strategy to strengthen his protégé Goukouni; it also weakened considerably Malloum's prestige among southern Chadians, who saw his concessions as a proof of his weak leadership.[31]

On 15 April, only a few days after signing the ceasefire, Goukouni left Faya, leaving there a Libyan garrison of 800 men. Relying on Libyan armor and airpower, Goukouni's forces conquered a small FAT garrison and pointed towards the capital N'Djamena.[5][31]

Against these stood freshly arrived French forces. Already in 1977, after Goukouni's first offensives, Malloum had asked for a French military return in Chad, but President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing was at first reluctant to commit himself before the carrying out of the legislative elections, held in March 1978; also, France was afraid of damaging its profitable commercial and diplomatic relations with Libya. At the end, the rapid deterioration of the situation in Chad resolved the President on February 20, 1978 to start Opération Tacaud, that by April brought in Chad 2,500 troops to secure the capital from the rebels.[32]

The decisive battle took place at Ati, a town 270 miles northeast of N'Djamena. The town's garrison of 1,500 soldiers was attacked on May 19 by the FROLINAT insurgents, equipped with artillery and modern weapons. The garrison was relieved by the arrival supported by armor of a Chadian task force and, more importantly, of the Foreign Legion and the 3rd Regiment of Marine Infantry; in a two-day battle, the FROLINAT was repelled with heavy losses, a victory that was confirmed in June by another engagement at Djedaa, after which the FROLINAT admitted defeat and fled north, after having lost 2,000 men and left the "ultramodern equipment" they carried on the ground. Of key importance in these battles was the complete air superiority the French could count on, as the Libyan Air Force pilots refused to fight the French.[31][33][34]

Libyan difficulties

Only a few months after the failed offensive against the capital, major dissensions in the FROLINAT shattered all vestiges of unity and badly weakened Libyan power in Chad. On the night of August 27 Ahmat Acyl, leader of the Volcan Army, attacked Faya-Largeau with the support of Libyan troops in what was apparently an attempt by Gaddafi to remove Goukouni from the leadership of the FROLINAT, replacing him with Acyl. The attempt backfired, as Goukouni reacted by expelling all Libyan military advisors present in Chad, and started searching for a compromise with France.[35][36]

The reasons for the clash between Gaddafi and Goukouni were both ethnic and political. The FROLINAT was divided between Arabs, like Acyl, and Toubous, like Goukouni and Habré. These ethnic divisions also reflected a different attitude towards Gaddafi and his Green Book. In particular, Goukouni and his men had shown themselves reluctant to follow Gaddafi's solicitations to make The Green Book the official policy of the FROLINAT, and had first tried to take time, leaving the question to the complete reunification of the movement. When the unification was accomplished, and Gaddafi pressed again for the adoption of The Green Book, the dissensions in the Revolution's Council became manifest, with many proclaiming their loyalty to the movement's original platform approved in 1966 when Ibrahim Abatcha was made first secretary-general, while others, among whom Acyl, fully embraced the Colonel's ideas.[37]

In N'Djamena, the contemporary presence of two armies, the FAN of the Prime Minister Habré and the FAT of the President Malloum, prepared the stage for the battle of N'Djamena, which was to bring about the collapse of the State and the ascent to power of the Northern elite. A minor incident escalated on February 12, 1979 into heavy fighting between Habré and Malloum's forces, and the battle intensified on February 19 when Goukouni's men entered in the capital to fight alongside Habré against the FAT. It is estimated that by March 16, when the first international peace conference took place, 2,000–5,000 people were killed and 60,000–70,000 forced to flee the capital, and the greatly diminished Chadian army left the capital in the rebels' hand and reorganized itself in the south under the leadership of Wadel Abdelkader Kamougué. During the battle, the French garrison stood passively by, even helping Habré in certain circumstances, as when they demanded the Chad Air Force to stop its bombings.[38]

An international peace conference was held in Kano in Nigeria, to which Chad's bordering states participated with Malloum for the Chadian army, Habré for the FAN and Goukouni for the FAP. The Kano Accord was signed on March 16 by all those present, and Malloum resigned, replaced by a Council of State under the chairmanship of Goukouni.[39] This was a result of Nigerian and French pressures on Goukouni and Habré to share power;[40] the French in particular saw this as part of their strategy to cut all ties between Goukouni and Gaddafi.[41] A few weeks later, the same factions formed the Transitional Government of National Unity (GUNT), kept together to a considerable extent by the common desire to see Libya out of Chad.[42]

Despite signing the Kano Accord,[43] Libya was incensed that the GUNT did not include any of the leaders of the Volcan Army and had not recognized Libyan claims on the Aouzou Strip. Already since 13 April there had been some minor Libyan military activity in northern Chad, and support was provided to the secessionist movement in the south, but a major response came only after June 25, when the ultimatum for the formation of a new, more inclusive, coalition government posed by Chad's bordering states to the GUNT expired. On June 26, 2,500 Libyan troops invaded Chad directed to Faya-Largeau. The Chadian government appealed for French help. The Libyan forces were first stymied by Goukouni's militiamen, and then forced to retreat by French reconnaissance planes and bombers. In the same month, the factions excluded by the GUNT founded a counter-government, the Front for Joint Provisional Action (FACP), in northern Chad with Libyan military support.[40][42][44]

The fighting with Libya, the imposition by Nigeria of an economic boycott and international pressure brought to a new international peace conference in Lagos in August, to which all eleven factions present in Chad participated. A new accord was signed on August 21, under which a new GUNT was to be formed, open to all factions. The French troops were to leave Chad, and be replaced by a multinational African peace force.[45] The new GUNT took office in November, with Goukouni President, Kamougué Vice-President, Habré Defence Minister[46] and Acyl Foreign Minister.[47] Despite the presence of Habré, the new composition of the GUNT had enough pro-Libyans to satisfy Gaddafi.[48]

Libyan intervention

It became clear from the start that Habré isolated himself from the other members of the GUNT, which he treated with disdain. Habré's hostility for Libya's influence in Chad united itself with his ambition and ruthlessness: observers concluded that the warlord would never be content with anything short of the highest office. In such a context it was thought that sooner or later an armed confrontation between Habré and the pro-Libyan factions would take place, and more importantly, between Habré and Goukouni.[46]

As expected, clashes in the capital between Habré's FAN and pro-Libyan groups became progressively more serious; in the end, on March 22, 1980 a minor incident, like in 1979 with the first, triggered the second battle of N'Djamena. In ten days, the clashes between the FAN and Goukouni's FAP, who both had 1,000–1,500 troops in the city, had caused thousands of casualties and the flight of about half the capital's population. The few remaining French troops, who left on May 4, proclaimed themselves neutral, as did the Zairian peace force.[49][50]

While the FAN was supplied economically and militarily by Sudan and Egypt, Goukouni received shortly after the beginning of the battle the armed support of Kamougué's FAT and Acyl's CDR, and was provided with Libyan artillery. On June 6, the FAN assumed control of the city of Faya; this alarmed Goukouni, and he signed, on June 15, a Treaty of Friendship with Libya. The treaty gave Libya a free hand in Chad, legitimising its presence in that country: this was especially evident in the first article of the treaty, where it was written that the two countries were committed to mutual defence, and a threat against one constituted a threat against the other.[50][51]

Beginning in October, Libyan troops airlifted to the Aouzou Strip operated in conjunction with Goukouni's forces to reoccupy Faya. The city was then used as an assembly point for tanks, artillery and armored vehicles that moved south against the capital of N'Djamena.[52]

An attack started on December 6, spearheaded by Soviet T-54 and T-55 tanks and reportedly coordinated by advisors from the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic, brought the fall of the capital on December 16. The Libyan force, numbering between 7,000 and 9,000 men of regular units and the paramilitary Pan-African Islamic Legion, 60 tanks, and other armored vehicles, had been ferried across 1,100 kilometers of desert from Libya's southern border, partly by airlift and tank transporters and partly under their own power. The border itself was 1,000 to 1,100 kilometers from Libya's main bases on the Mediterranean coast.[52] The Libyan intervention demonstrated an impressive logistical ability, and provided Gaddafi with his first military victory and a substantial political achievement.[53]

While forced into exile and with his forces confined to the frontier zones of Darfur, Habré remained defiant: on December 31 he announced in Dakar he would resume fighting as a guerrilla against the GUNT.[50][53]

Libyan withdrawal

On January 6, 1981, a joint comuniqué was issued in Tripoli by Gaddafi and Goukouni that Libya and Chad had decided "to work to achieve full unity between the two countries". The merger plan caused strong adverse reaction in Africa, and was immediately condemned by France, that on January 11 offered to strengthen French garrisons in friendly African states and on January 15 placed the French Mediterranean fleet on alert. Libya answered by threatening to impose an oil embargo, while France threatened to react if Libya attacked another bordering country. The accord was also opposed by all GUNT ministers present with Goukouni at Tripoli, with the exception of Acyl.[47][54]

Most observers believe that the reasons behind Goukouni's accepting the accord may be found in a mix of threats, intense pressure and the financial help promised by Gaddafi. Also, just before his visit to the Libyan capital, Goukouni had sent two of his commanders to Libya for consultations; at Tripoli, Goukouni learned from Gaddafi that they had been assassinated by "Libyan dissidents", and that if he didn't want to risk losing Libyan favour and lose power, he should accept the merger plan.[55]

The importance of the opposition they met caused Gaddafi and Goukouni to downplay the importance of the communiqué, speaking of a "union" of peoples, and not of states, and as a "first step" towards closer collaboration. But the damage had been done, and the joint communiqué badly weakened Goukouni's prestige as a nationalist and a statesman.[47]

Increasing international pressure against Libyan presence in Chad were at first met by Goukouni's statement that the Libyans were present in Chad because requested by the government, and that international mediators should simply accept the decision of Chad's legitimate government. In a meeting held in May Goukouni had become more accommodating, declaring that while the Libyan forces withdrawal was not a priority, he would accept the decisions of the OAU. Goukouni could hardly at the time renounce Libyan military support, necessary for dealing with Habré's FAN, which was supported by Egypt and Sudan and funded through Egypt by the United States Central Intelligence Agency.[56]

In the meantime, relations between Goukouni and Gaddafi started deteriorating. Libyan troops were stationed in various points of northern and central Chad, in numbers that had reached by January–February about 14,000 troops. The Libyan forces in the country created considerable annoyance in the GUNT, by supporting Acyl's faction in its disputes with the other militias, including the clashes held in late April with Goukouni's FAP. There were also attempts to Libyanize the local population, that made many conclude that "unification" for Libya meant Arabization and the imposition of Libyan political culture, in particular of The Green Book.[57][58][59]

Amid fighting in October between Gaddafi's Islamic Legionnaires and Goukouni's troops, and rumors that Acyl was planning a coup d'état to assume the leadership of the GUNT, Goukouni demanded on October 29 the complete and unequivocal withdrawal of Libyan forces from Chadian territory, which, beginning with the capital, was to be completed by December 31. The Libyans were to be replaced by an Organization for African Unity (OAU) Inter-African Force (IAF). Gaddafi complied, and by November 16 all Libyan forces had left Chad, redeploying in the Aouzou Strip.[58][59]

Libya's prompt retreat took many observers by surprise. Reasons were to be found in Gaddafi's desire to host the OAU's annual conference in 1982 and assume the presidency of the OAU for that year. Another point could be found in Libya's difficult situation in Chad where, without some popular and international acceptance for Libyan presence, it would have been difficult to take the concrete risk of causing a war with Egypt and Sudan, with US support. This does not mean that Gaddafi had renounced the goals he had set for Chad, but that he now had to search for somebody else as Chad's leader, as Goukouni had proved himself unreliable.[59][60]

Habré takes N'Djamena

The first IAF component to arrive in Chad were the Zairian paratroopers; they were followed by Nigerian and Senegalese forces, bringing the IAF to 3,275 men. Before the peace-keeping force was fully deployed, Habré had already taken advantage of Libya's withdrawal, and made massive inroads in eastern Chad, including the important city of Abéché, that fell on November 19.[61] Next to fall was in early January Oum Hadjer, at only 100 miles from Ati, the last relevant town before the capital. The GUNT was saved for the moment by the IAF, the only credible military force confronting Habré, that prevented the FAN from taking Ati.[62]

In the light of Habré's offensive, the OAU requested the GUNT to open reconciliation talks with Habré, a demand that was angrily refused by Goukouni;[63] later he was to say:

"The OAU has deceived us. Our security was fully ensured by Libyan troops. The OAU put pressure on us to expel the Libyans. Now that they have gone, the organization has abandoned us while imposing on us a negotiated settlement with Hissein Habre"[64]

In May, the FAN started a final offensive, passing unhindered by the peacekeepers in Ati and Mongo.[64] Goukouni, increasingly angered with the IAF's refusal to fight Habré, made an attempt to restore his relations with Libya, and reached Tripoli on May 23, but Gaddafi, burned by his experience the previous year, proclaimed his state neutrality in the civil war.[65]

The GUNT forces attempted to make a last stand at Massaguet, 50 miles north of capital on the Abéché-N'Djamena road, but were defeated by the FAN on June 5 after a hard battle. Two days later Habré entered unopposed in N'Djamena, making him the de facto source of national government in Chad, while Goukouni fled the country seeking sanctuary in Cameroon.[66][67]

Immediately after occupying the capital, Habré proceeded to consolidate his power by occupying the rest of the country. In barely six weeks, he conquered southern Chad, destroying the FAT, Kamougué's militia, whose hopes for Libyan help failed to materialize. Also the rest of the country was submitted, with the exception of the Tibesti.[68]

GUNT offensive

Since Gaddafi had kept himself mostly aloof in the months prior to the fall of N'Djamena, Habré hoped at first to reach an understanding with Libya, possibly through an accord with its proxy in Chad, the leader of the Revolutionary Democratic Council (CDR) Ahmat Acyl, who appeared receptive to dialogue. But Acyl died on July 19, replaced by Acheikh ibn Oumar, and the CDR was antagonized by Habré's eagerness to unify the country, making him overrun the CDR's domains.[69]

Therefore, it was with Libyan support that Goukouni reassembled the GUNT, creating in October a National Peace Government with its seat in the Tibesti town of Bardaï and claiming itself the legitimate government by the terms of the Lagos Accord. For the impending fight Goukouni could count on 3,000–4,000 men taken from several militias, later merged in an Armée Nationale de Libération (ANL) under the command of a Southerner, Negue Djogo.[70][71]

Before Gaddafi could throw his full weight behind Goukouni, Habré attacked the GUNT in the Tibesti, but was repelled both in December 1982 and in January 1983. The following months saw the clashes intensify in the North, while talks, with even an exchange in March of visits between Tripoli and N'Djamena, broke down. Therefore, on March 17 Habré brought the Chad-Libya quarrel before the United Nations, asking for an urgent meeting of the UN Security Council to consider Libya's "aggression and occupation" of Chadian territory.[70][72]

Gaddafi was ready now for an offensive. The decisive offensive began in June, when a 3,000 strong GUNT force invested Faya-Largeau, the main government stronghold in the North, that fell on June 25, and then rapidly proceeded towards Koro Toro, Oum Chalouba and Abéché, assuming control of the main routes towards N'Djamena. Libya, while helping with recruiting and training and providing the GUNT with heavy artillery, only committed a few thousand regular troops to the offensive, and most of these were artillery and logistic units. This may have been due to Gaddafi's desire that the conflict should be read as a Chadian internal affair.[52][66][70]

The international community reacted adversely to the Libyan-backed offensive, in particular France and the United States. On the same day as the fall of Faya, the French Foreign Minister Claude Cheysson warned Libya that France would "not remain indifferent" to a new Libyan involvement in Chad, and on July 11 the French government accused again Libya of direct military support to the rebels. French arms shipments were resumed on June 27, and on July 3 a first contingent of 250 Zairians arrived to strengthen Habré; the United States announced in July military and food aid for 10 million dollars. Gaddafi suffered also a diplomatic setback from the OAU, that at the meeting held in June officially recognized Habré's government and asked for all foreign troops to leave Chad.[70][72][73]

Supplied by Americans, Zairians and the French, Habré rapidly reorganized his forces (now called Chadian National Armed Forces or FANT) and marched north to confront the GUNT and the Libyans, that he met south of Abéché. Habré proved again his ability, crushing Goukouni's forces, and started a vast counteroffensive that enabled him to retake in rapid succession Abéché, Biltine, Fada and, on July 30, Faya-Largeau, threatening to attack the Tibesti and the Aouzou Strip.[70]

French intervention

Main article: Opération MantaFeeling that a complete destruction of the GUNT would be an intolerable blow for his prestige, and fearing that Habré would provide support for all opposition to Gaddafi, the Colonel called for a Libyan intervention in force, as his Chadian allies could not secure a definitive victory without Libyan armor and airpower.[74]

Since the day after the fall of the town, Faya-Largeau was subjected to a sustained air bombardment, using Su-22 and Mirage F-1s from the Aouzou air base, along with Tu-22 bombers from Sabha. Within ten days, a large ground force had been assembled east and west of Faya-Largeau by first ferrying men, armor, and artillery by air to Sabha, Al Kufrah, and the Aouzou airfield, and then by shorter range transport planes to the area of conflict. The fresh Libyan forces amounted to 11,000 mostly regular troops, and eighty combat aircraft participated to the offensive; nowithstanding this, the Libyans maintained their traditional role of providing fire support, and occasional tank charges, for the assaults of the GUNT, that could count on 3,000–4,000 men on this occasion.[52][75]

The GUNT-Libyan alliance invested on August 10 the Faya-Largeau oasis, where Habré had entrenched himself with about 5,000 troops. Battered by multiple rocket launcher (MRL), artillery and tank fire and continuous airstrikes, the FANT's defensive line disintegrated when the GUNT launched the final assault, leaving 700 FANT troops on the ground. Habré escaped with the remnants of his army to the capital, without being pursued by the Libyans.[75]

This was to prove a tactical blunder, as the new Libyan intervention had alarmed France. Habré issued a fresh plea for French military assistance on August 6.[76] France, also due to American and African pressures, announced on August 6 the return of French troops in Chad as part of Opération Manta, meant to stop the GUNT-Libyan advance and more generally weaken Gaddafi's influence in the internal affairs of Chad. Three days later several hundred French troops were dispatched to N'Djamena from the Central African Republic, that were later brought to 2,700, with several squadron of Jaguar fighter-bombers. This made it the largest expeditionary force ever assembled by the French in Africa, except for the Algerian War of Independence.[75][77][78][79]

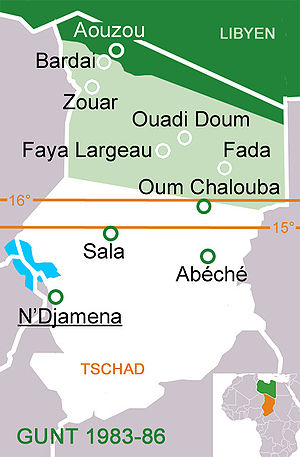

The French government then defined a limit (the so-called Red Line), along the 15th parallel, extending from Mao to Abéché, and warned that they would not tolerate any incursion south of this line by Libyan or GUNT forces. Both the Libyans and the French remained on their side of the line, with France showing itself unwilling to help Habré retake the north, while the Libyans avoided starting a conflict with France by attacking the line. This led to a de facto division of the country, with Libya maintaining control of all the territory north of the Red Line.[52][77]

A lull ensued, during which in November talks sponsored by the OAU failed to conciliate the opposing Chadian factions; no more successful was Ethiopia's leader Mengistu's attempt at the beginning of 1984. Mengistu's failure was followed on January 24 by a GUNT attack, supported by heavy Libyan armor, on the FANT outpost of Ziguey, a move mainly meant to persuade France and the African states to reopen negotiations. France reacted to this breach of the Red Line by launching the first significant air counter-attack, bringing into Chad new troops and unilaterally raising the defensive line to the 16th parallel.[80][81][82]

French withdrawal

To put an end to the deadlock, Gaddafi proposed on April 30 a mutual withdrawal of both the French and Libyan forces in Chad. The French President François Mitterrand showed himself receptive to the offer, and on September 17 the two leaders publicly announced that the mutual withdrawal would start on September 25, and be completed by November 10.[80] The accord was at first hailed by the media as a proof attesting Mitterrand's diplomatic skills and a decisive progress towards the solution of the Chadian crisis;[83] it also answered Mitterrand's intent of following regards Libya and Chad a foreign policy independent from both the United States and the Chadian government.[77]

While France respected the deadline, the Libyans limited themselves to retiring some forces, while maintaining at least 3,000 men stationed in Northern Chad. When this became evident, it resulted in a source of considerable embarrassment for the French and the occasion of recriminations between the French and Chadian governments.[84] On November 16 Mitterrand met with Gaddafi on Crete, under the auspices of the Greek prime minister Papandreou. Despite Gaddafi's declaration that all Libyan forces had been withdrawn, the next day Mitterrand admitted that this was not true but did not order French troops back to Chad.[85]

According to Nolutshungu, the 1984 bilateral Franco-Libyan agreement may have provided Gaddafi with an excellent opportunity to find an exit from the Chadian quagmire, while bolstering his international prestige and posing him in a condition to force Habré into accepting a peace accord which would have included Libya's proxies. Instead, Gaddafi misread France's withdrawal as a willingness to accept Libya's military presence in Chad and the de facto annexation of the whole BET Prefecture by Libya, an action that was certain to meet the opposition of all Chadian factions and of the OAU and the UN. Gaddafi's blunder would eventually bring about his defeat, with the rebellion against him of the GUNT and a new French expedition in 1986.[86]

New French intervention

Main article: Opération EpervierDuring the period between 1984 and 1986, in which no major clash took place, Habré greatly strengthened his position thanks to staunch US support and Libya's failure to respect the Franco-Libyan 1984 agreement. Also decisive was the increasing factional bickering that started plaguing the GUNT since 1984, centered around the fight between Goukouni and Acheikh ibn Oumar over the leadership of the organization.[87]

In this period, Gaddafi expanded his control over northern Chad, building new roads and erecting a major new airbase, Ouadi Doum, meant to better support air and ground operations beyond the Aouzou Strip, and brought in considerable reinforcements in 1985, rising their forces in the country to 7,000 troops, 300 tanks and 60 combat aircraft.[88] While this build-up took place, significant elements of the GUNT passed over to the Habré government, as part of the latter's policy of accommodation.[89]

These desertions alarmed Gaddafi, as the GUNT provided a cover of legitimacy to Libya's presence in Chad. To put a halt to these and reunite the GUNT, a major offensive was launched on the Red Line, whose ultimate goal was N'Djamena itsef. The attack, started on February 10, involved 5,000 Libyan and 5,000 GUNT troops, and concentrated on the FANT outposts of Kouba Olanga, Kalait and Oum Chalouba. The campaign ended in disaster for Gaddafi, when a FANT counteroffensive on February 13 using the new equipment obtained from the French forced the attackers to withdraw and reorganize.[82][89][90]

Most important was French reaction to the attack. Gaddafi had possibly believed that, due to the upcoming French legislative elections, Mitterrand would have been reluctant to start a new risky and costly expedition to save Habré; this evaluation proved wrong, as what the French President could not politically risk was to show weakness towards Libyan aggression. As a result, on 14 February Opération Epervier was started, bringing 1,200 French troops and several squadrons of Jaguars in Chad. On 16th Feb, to send a clear message to Gaddafi, the French Air Force bombed Libya's Ouadi Doum airbase. Libya retaliated the next day when a Libyan Tupolev Tu-22 bombed the N'Djamena Airport causing minimal damage.[90][91][92]

Tibesti War

The defeats suffered in February and March accelerated the disintegration of the GUNT. When in March, at a new round of OAU-sponsored talks held in the People's Republic of Congo, Goukouni failed to appear, many suspected the hand of Libya, causing the defection from the GUNT of its Vice-president Kamougué, followed by the First Army and the pichipichi FROLINAT Originel. In August, it was the CDR's turn to leave the coalition, seizing the town of Fada. When in October Goukouni's FAP attempted to retake Fada, the Libyan garrison attacked Goukouni's troops, giving way to a pitched battle that effectively ended the GUNT. In the same month, Goukouni was arrested by the Libyans, while his troops rebelled against Gaddafi, dislodging the Libyans from all their positions in the Tibesti, and on October 24 went over to Habré.[93]

To reestablish their supply lines and retake the towns of Bardaï, Zouar and Wour, the Libyans sent a task-force of 2,000 troops with T-62 tanks and heavy support by the Libyan Air Force into Tibesti. The offensive started successfully, expelling the GUNT from its key strongholds, also through the use of napalm and, allegedly, poison gas. This attack ultimately backfired, causing the prompt reaction of Habré, who sent 2,000 FANT soldiers to link with the GUNT forces. Also Mitterrand reacted forcefully, ordering a mission which parachuted fuel, food, ammunition and anti-tank missiles to the rebels, and also infiltrated military personnel. Through this action, the French made clear that they no longer felt committed to keep south of the Red Line, and were ready to act whenever they found it necessary.[94][95]

While militarily Habré was only partly successful in his attempt to evict the Libyans from the Tibesti (the Libyans would fully leave the region in March, when a series of defeats in the north-east had made the area untenable), the campaign was a great strategic breakthrough for the FANT, as it transformed a civil war into a national war against a foreign invader, stimulating a sense of national unity that had never been seen before in Chad.[96]

Toyota War

Main article: Toyota WarAt the opening of 1987, the last year of the war, the Libyan expeditionary force was still impressive, counting on 8,000 troops and 300 tanks; but it had lost the key support of its Chadian allies, who had generally provided reconnaissance and acted as assault infantry. Without them the Libyan garrisons resembled isolated and vulnerable islands in the Chadian desert. On the other side, the FANT was greatly strengthened, now having 10,000 highly motivated troops, provided with fast-moving and sand-adapted Toyota trucks equipped with MILAN anti-tank guided missiles, that gave the name of "Toyota War" to the last phase of the Chadian–Libyan conflict.[97][98][99]

Habré started, on January 2, 1987, his reconquest of northern Chad with a successful attack of the well-defended Libyan communications base of Fada. Against the Libyan army the Chadian commander Hassan Djamous conducted a series of swift pincer movements, enveloping the Libyan positions and crushing them with sudden attacks from all sides. This strategy was repeated by Djamous in March in the battles of B'ir Kora and Ouadi Doum, inflicting crushing losses and forcing Gaddafi to evacuate northern Chad.[100]

This in turn endangered Libyan control over the Aouzou Strip, and Aouzou fell in August to the FANT, only to be repelled by an overwhelming Libyan counter-offensive and the French refusal to provide air cover to the Chadians. Habré readily replied to this setback with the first Chadian incursion in Libyan territory of the Chadian–Libyan conflict, mounting on September 5 a surprise and fully successful raid against the key Libyan air base at Maaten al-Sarra. This attack was part of a plan to remove the threat of Libyan airpower before a renewed offensive on Aouzou.[101]

The projected attack on Aouzou never took place, as the dimensions of the victory obtained at Maaten made France fear that the attack on the Libyan Base was only the first stage of a general offensive into Libya proper, a possibility that France was not willing to tolerate. As for Gaddafi, being subjected to internal and international pressures, he showed himself more conciliatory, which brought as a result to an OAU-brokered ceasefire on September 11.[102][103]

Aftermath

While there were many violations of the ceasefire, the incidents were relatively minor. The two governments immediately started complex diplomatic manoeuvres to bring world opinion on their side in the case, as widely expected, that the conflict was resumed; but the two sides were also careful to leave the door open for a peaceful solution. The latter course was promoted by France and most African states, while the Reagan Administration saw a resumption of the conflict as the best chance to unseat Gaddafi.[104]

Steadily, relations among the two countries improved, with Gaddafi giving signs that he wanted to normalize relations with the Chadian government, to the point of recognizing that the war had been an error. In May 1988 the Libyan leader declared he would recognize Habré as the legitimate president of Chad "as a gift to Africa"; this led on October 3 to the resumption of full diplomatic relations between the two countries. The following year, on August 31, 1989, Chadian and Libyan representatives met in Algiers to negotiate the Framework Agreement on the Peaceful Settlement of the Territorial Dispute, by which Gaddafi agreed to discuss with Habré the Aouzou Strip and to bring the issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a binding ruling if bilateral talks failed. Therefore, after a year of inconclusive talks, the sides submitted in September 1990 the dispute to the ICJ.[105][106][107]

Chadian-Libyan relations were further ameliorated when Libyan-supported Idriss Déby unseated Habré on December 2. Gaddafi was the first head of state to recognize the new regime, and he also signed treaties of friendship and cooperation on various levels; but regarding the Aouzou Strip Déby followed his predecessor, declaring that if necessary he would fight to keep the strip out of Libya's hands.[108][109]

The Aouzou dispute was concluded for good on February 3, 1994, when the judges of the ICJ by a majority of 16 to 1 decided that the Aouzou Strip belonged to Chad. The court's judgement was implemented without delay, the two parties signing as early as April 4 an agreement concerning the practical modalities for the implementation of the judgement. Monitored by international observers, the withdrawal of Libyan troops from the Strip began on April 15 and was completed by May 10. The formal and final transfer of the Strip from Libya to Chad took place on May 30, when the sides signed a joint declaration stating that the Libyan withdrawal had been effected.[107][110]

Libyan retaliation against France and the United States

Muammar Gaddafi was angered by the devastating counter-attack on Libya and the ensuing defeat at the Battle of Maaten al-Sarra. Forced to accede to a ceasefire, the defeat ended his expansionist projects toward Chad and his dreams of African and Arab dominance.[111]

Given the French intervention on behalf of Chad and U.S. supply of satellite intelligence to FANT during the battle of Maaten al-Sarra, Gaddafi blamed Libya's defeat on French and U.S. "aggression against Libya".[112] The U.S. did not conceal its satisfaction over the Libyan defeat with an official stating that "We basically jump for joy every time the Chadians ding the Libyans". The result was Gaddafi's lingering animosity against the two countries which led to Libyan support for the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland on 21 December 1988, and the bombing of UTA Flight 772 on 19 September 1989.[113]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Libya and the West: from independence to Lockerbie By Geoffrey Leslie Simons, Centre for Libyan Studies (Oxford, England). Pg. 57

- ^ Libya and the West: from independence to Lockerbie By Geoffrey Leslie Simons, Centre for Libyan Studies (Oxford, England). Pg. 57-58

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ a b c d e f K. Pollack, Arabs at War, p. 375

- ^ a b c d e K. Pollack, p. 376

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, Limits of Anarchy, p. 230

- ^ M. Azevedo, Roots of Violence, p. 151

- ^ A. Clayton, Frontiersmen, p. 98

- ^ M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, A Study of Crisis, p. 84

- ^ R. Brian Ferguson, The State, Identity and Violence, p. 267

- ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=V6M1AAAAIBAJ&sjid=KbcFAAAAIBAJ&pg=1639,5039146&hl=en

- ^ a b G. Simons, Libya and the West, p. 56

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 327

- ^ a b M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 85

- ^ a b c J. Wright, Libya, Chad and the Central Sahara, p. 130

- ^ M. Azevedo, p. 145

- ^ (PDF) Public sitting held on Monday 14 June 1993 in the case concerning Territorial Dispute (Libyan Arab Jamayiriya/Chad). International Court of Justice. http://www.icj-cij.org/cijwww/ccases/cdt/cDT_cr/cDT_cCR9314_19930614.PDF.

- ^ R. Buijtenhuijs, "Le FROLINAT à l'épreuve du pouvoir", p. 19

- ^ R. Buijtenhuijs, pp. 16–17

- ^ (PDF) Public sitting held on Friday 2 July 1993 in the case concerning Territorial Dispute (Libyan Arab Jamayiriya/Chad). International Court of Justice. http://www.icj-cij.org/cijwww/ccases/cdt/cDT_cr/cDT_cCR9326_19930702.PDF.

- ^ A. Clayton, p. 99

- ^ J. Wright, pp. 130–131

- ^ S. Macedo, Universal Jurisdiction, pp. 132–133

- ^ R. Buijtenhuijs, Guerre de guérilla et révolution en Afrique noire, p. 27

- ^ A. Gérard, Nimeiry face aux crises tchadiennes, p. 119

- ^ a b c M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 86

- ^ a b R. Buijtenhuijs, Guerre de guérilla et révolution en Afrique noire, p. 26

- ^ R. Buijtenhuijs, "Le FROLINAT à l'épreuve du pouvoir", p. 18

- ^ Libya-Sudan-Chad Triangle, p. 32

- ^ R. Buijtenhuijs, "Le FROLINAT à l'épreuve du pouvoir", p. 21

- ^ a b c d M. Azevedo, p. 146

- ^ J. de Léspinôis, "L'emploi de la force aeriénne au Tchad", pp. 70–71

- ^ M. Pollack, pp. 376–377

- ^ H. Simpson, The Paratroopers of the French Foreign Legion, p. 55

- ^ M. Brandily, "Le Tchad face nord", p. 59

- ^ N. Mouric, "La politique tchadienne de la France", p. 99

- ^ M. Brandily, pp. 58–61

- ^ M. Azevedo, pp. 104–105, 119, 135

- ^ Ibid., p. 106

- ^ a b M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 88

- ^ N. Mouric, p. 100

- ^ a b K. Pollack, p. 377

- ^ T. Mays, Africa's First Peacekeeping operation, p. 43

- ^ T. Mays, p. 39

- ^ T. Mays, pp. 45–46

- ^ a b S. Nolutshungu, p. 133

- ^ a b c M. Azevedo, p. 147

- ^ J. Wright, p. 131

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 135

- ^ a b c M. Azevedo, p. 108

- ^ M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 89

- ^ a b c d e H. Metz, Libya, p. 261

- ^ a b J. Wright, p. 132

- ^ M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, pp. 89–90

- ^ M. Azevedo, pp. 147–148

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 156

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 153

- ^ a b M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 90

- ^ a b c M. Azevedo, p. 148

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 154–155

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 164

- ^ T. Mays, pp. 134–135

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 165

- ^ a b T. Mays, p. 139

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 168

- ^ a b K. Pollack, p. 382

- ^ T. Mays, p. 99

- ^ S.Nolutshungu, p. 186

- ^ Ibid. p. 185

- ^ a b c d e S. Nolutshungu, p. 188

- ^ M. Azevedo, p. 110, 139

- ^ a b M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 91

- ^ M. Azevedo, p. 159

- ^ K. Pollack, pp. 382–383

- ^ a b c K. Pollack, p. 383

- ^ J. Jessup, An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict, p. 116

- ^ a b c S. Nolutshungu, p. 189

- ^ M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, pp. 91–92

- ^ M. Azevedo, p. 139

- ^ a b M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 92

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 191

- ^ a b M. Azevedo, p. 110

- ^ M. Azevedo, pp. 139–140

- ^ M. Azevedo, p. 140

- ^ G.L. Simons, p. 293

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 202–203

- ^ Ibid., pp. 191–192, 210

- ^ K. Pollack, pp. 384–385

- ^ a b S. Nolutshungu, p. 212

- ^ a b K. Pollack, p. 389

- ^ M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 93

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 212–213

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 213–214

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 214–216

- ^ K. Pollack, p. 390

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 215–216, 245

- ^ M. Azevedo, pp. 149–150

- ^ K. Pollack, p. 391, 398

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 218–219

- ^ K. Pollack, pp. 391–394

- ^ K. Pollack, pp. 395–396

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 222–223

- ^ K. Pollack, p. 397

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, pp. 223–224

- ^ G. Simons, p. 58, 60

- ^ S. Nolutshungu, p. 227

- ^ a b M. Brecher & J. Wilkenfeld, p. 95

- ^ "Chad The Devil Behind the Scenes". Time. 1990-12-17. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,971950,00.html?iid=chix-sphere.

- ^ M. Azevedo, p. 150

- ^ G. Simons, p. 78

- ^ The French military role in Chad

- ^ Greenwald, John (1987-09-21). "Disputes Raiders of the Armed Toyotas". Time. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,965563,00.html

- ^ http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19890919-1

References

- Azevedo, Mario J. (1998). Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Routledge. ISBN 90-5699-582-0.

- Brandily, Monique (December 1984). "Le Tchad face nord 1978-1979" (PDF). Politique Africaine (16): 45–65. http://www.politique-africaine.com/numeros/pdf/016045.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Brecher, Michael & Wilkenfeld, Jonathan (1997). A Study in Crisis. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-4721-0806-9.

- Buijtenhuijs, Robert (December 1984). "Le FROLINAT à l'épreuve du pouvoir: L'échec d'une révolution Africaine" (PDF). Politique Africaine (16): 15–29. http://www.politique-africaine.com/numeros/pdf/016015.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Buijtenhuijs, Robert (March 1981). "Guerre de guérilla et révolution en Afrique noire : les leçons du Tchad" (PDF). Politique Africaine (1): 23–33. http://www.politique-africaine.com/numeros/pdf/001023.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Brian Ferguson, R. (2002). State, Identity and Violence:Political Disintegration in the Post-Cold War World. Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-7412-5.

- Clayton, Anthony (1998). Frontiersmen: Warfare in Africa Since 1950. Routledge. ISBN 1-8572-8525-5.

- de Lespinois, Jérôme (June 2005). "L'emploi de la force aérienne au Tchad (1967–1987)" (PDF). Penser les Ailes françaises (6): 65–74. http://www.cesa.air.defense.gouv.fr/DPESA/PLAF/PLAF_N_6.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Gérard, Alain (December 1984). "Nimeiry face aux crises tchadiennes" (PDF). Politique Africaine (16): 118–124. http://www.politique-africaine.com/numeros/pdf/016118.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Macedo, Stephen (2003). Universal Jurisdiction: National Courts and the Prosecution of Serious Crimes Under International Law. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3736-6.

- Mays, Terry M. (2002). Africa's First Peacekeeping operation: The OAU in Chad. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-275-97606-4.

- Metz, Helen Chapin (2004). Libya. US GPO. ISBN 1-4191-3012-9. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/lytoc.html.

- Mouric, N. (December 1984). "La politique tchadienne de la France sous Valéry Giscard d'Estaing" (PDF). Politique Africaine (16): 86–101. http://www.politique-africaine.com/numeros/pdf/016086.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Nolutshungu, Sam C. (1995). Limits of Anarchy: Intervention and State Formation in Chad. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1628-3.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (2002). Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3733-2.

- Simons, Geoffrey Leslie (1993). Libya: The Struggle for Survival. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0312089979.

- Simons, Geoff (2004). Libya and the West: From Independence to Lockerbie. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-8606-4988-2.

- Simpson, Howard R. (1999). The Paratroopers of the French Foreign Legion: From Vietnam to Bosnia. Brassey's. ISBN 1-5748-8226-0.

- Wright, John L. (1989). Libya, Chad and the Central Sahara. C. Hurst. ISBN 1-85065-050-0.

- Libya-Sudan-Chad Triangle: Dilemma for United States Policy. US GPO. 1981.

External links

Categories:- Chadian–Libyan conflict

- Wars involving Libya

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving Chad

- 20th century in Libya

- 20th century in Africa

- 1980s in Africa

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.