- Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway

-

Sarin attack on the Tokyo subway

Kasumigaseki Station, one of the many stations affected during the attackLocation Tokyo, Japan Date March 20, 1995

7:00-8:10 a.m. (UTC+ 9)Target Tokyo Metro Attack type Chemical warfare Weapon(s) Sarin Death(s) 13 Injured 6,252(50 severe; 984 temporary vision problems) Perpetrator(s) Aum Shinrikyo The Sarin attack on the Tokyo subway, usually referred to in the Japanese media as the Subway Sarin Incident (地下鉄サリン事件 Chikatetsu Sarin Jiken), was an act of domestic terrorism perpetrated by members of Aum Shinrikyo on March 20, 1995.

In five coordinated attacks, the perpetrators released sarin on several lines of the Tokyo Metro, killing thirteen people, severely injuring fifty and causing temporary vision problems for nearly a thousand others. The attack was directed against trains passing through Kasumigaseki and Nagatachō, home to the Japanese government. It is the most serious attack to occur in Japan since the end of World War II.

Contents

Background

Aum Shinrikyo is the former name of a controversial group now known as Aleph. The Japanese police initially reported that the attack was the cult's way of hastening an apocalypse. The prosecution said that it was an attempt to bring down the government and install Shoko Asahara, the group's founder, as the "emperor" of Japan. Asahara's defense team claimed that certain senior members of the group independently planned the attack, but their motives for this were left unexplained.

Aum Shinrikyo first began their attacks on June 27, 1994 in Matsumoto, Japan. With the help of a converted refrigerator truck, members of the cult released a cloud of sarin which floated near the homes of judges who were overseeing a lawsuit concerning a real-estate dispute which was predicted to go against the cult. From this one event, 500 people were injured and seven people died.[1]

Main perpetrators

Ten men were responsible for carrying out the attacks; five released the sarin, while the other five served as get-away drivers.

The teams were:

Assigned Train Perpetrator Driver Chiyoda Line, train A725K Ikuo Hayashi (林 郁夫 Hayashi Ikuo) Tomomitsu Niimi (新実 智光 Niimi Tomomitsu) Marunouchi Line, train A777 Kenichi Hirose (広瀬 健一 Hirose Ken'ichi) Koichi Kitamura (北村 浩一 Kitamura Kōichi) Marunouchi Line, train B801 Toru Toyoda (豊田 亨 Toyoda Tōru) Katsuya Takahashi (高橋 克也 Takahashi Katsuya) Hibiya Line, train B711T Masato Yokoyama (横山 真人 Yokoyama Masato) Kiyotaka Tonozaki (外崎 清隆 Tonozaki Kiyotaka) Hibiya Line, train A720S Yasuo Hayashi (林 泰男 Hayashi Yasuo) Shigeo Sugimoto (杉本 繁郎 Sugimoto Shigeo) Ikuo Hayashi

Main article: Ikuo HayashiPrior to joining Aum, Hayashi was a senior medical doctor with "an active 'front-line' track record" at the Ministry of Science and Technology. Himself the son of a doctor, Hayashi graduated from Keio University, one of Tokyo's top schools. He was a heart and artery specialist at Keio Hospital, which he left to become head of Circulatory Medicine at the National Sanatorium Hospital in Tokai, Ibaraki (north of Tokyo). In 1990, he resigned his job and left his family to join Aum in the monastic order Sangha, where he became one of Asahara's favorites and was appointed the group's Minister of Healing, as which he was responsible for administering a variety of "treatments" to Aum members, including sodium pentothal and electric shocks to those whose loyalty was suspect. These treatments resulted in several deaths. Hayashi was later sentenced to life imprisonment.

Tomomitsu Niimi, who was his get-away driver, received the death sentence due to his involvement in other crimes perpetrated by Aum members.

Kenichi Hirose

Hirose was thirty years old at the time of the attacks. Holder of a postgraduate degree in Physics from prestigious Waseda University, Hirose became an important member of the group's Chemical Brigade in their Ministry of Science and Technology. He was also involved in the group's Automatic Light Weapon Development scheme.

Hirose teamed up with Koichi Kitamura, who was his get-away driver. After releasing the sarin, Hirose himself showed symptoms of sarin poisoning. He was able to inject himself with the antidote (atropine sulphate) and was rushed to the Aum-affiliated Shinrikyo Hospital in Nakano for treatment. However, medical personnel at the given hospital had not been given prior notice of the attack and were consequently clueless regarding what treatment Hirose needed. When Kitamura faced the fact that he had driven Hirose to the hospital in vain, he instead drove to Aum's headquarter in Shibuya where Ikuo Hayashi gave Hirose first aid.

Hirose's appeal of his death sentence was rejected by the Tokyo High Court on Wednesday, July 28, 2003. The sentence was upheld by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 6, 2009.[2]

Kitamura was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Toru Toyoda

Toyoda was twenty-seven at the time of the attack. He studied Applied Physics at University of Tokyo's Science Department and graduated with honors. He also holds a master's degree, and was about to begin doctoral studies when he joined Aum, where he belonged to the Chemical Brigade in their Ministry of Science and Technology.

Toyoda was sentenced to death. The appeal of his death sentence was rejected by the Tokyo High Court on Wednesday, July 28, 2003, and was upheld by the Supreme Court on November 6, 2009.[2]

Katsuya Takahashi was his get-away driver and is still at large.

Masato Yokoyama

Yokoyama was thirty-one at the time of the attack. He was a graduate in Applied Physics from Tokai University's Engineering Department. He worked for an electronics firm for three years after graduation before leaving to join Aum, where he became Undersecretary at the group's Ministry of Science and Technology. He was also involved in their Automatic Light Weapons Manufacturing scheme. Yokoyama was sentenced to death in 1999.

Kiyotaka Tonozaki, a high school graduate who joined the group in 1987, was a member of the group's Ministry of Construction, and served as Yokoyama's getaway driver. Tonozaki was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Yasuo Hayashi

Yasuo Hayashi was thirty-seven years old at the time of the attacks, and was the oldest person at the group's Ministry of Science and Technology. He studied Artificial Intelligence at Kogakuin University; after graduation he traveled to India where he studied yoga. He then became an Aum member, taking vows in 1988 and rising to the number three position in the group's Ministry of Science and Technology.

Asahara had at one time suspected Hayashi of being a spy. The extra packet of sarin he carried was part of "ritual character test" set up by Asahara to prove his allegiance, according to the prosecution.

Hayashi went on the run after the attacks; he was arrested twenty-one months later, one thousand miles from Tokyo on Ishigaki Island. He was later sentenced to death and has appealed.

Shigeo Sugimoto was his get-away driver. His lawyers argued that he played only a minor role in the attack, but the argument was rejected, and he has been sentenced to death.

Attack

On Monday March 20, 1995, five members of Aum Shinrikyo launched a chemical attack on the Tokyo Metro, one of the world's busiest commuter transport systems, at the peak of the morning rush hour. The chemical agent used, liquid sarin, was contained in plastic bags which each team then wrapped in newspaper. Each perpetrator carried two packets of sarin totaling approximately 900 millilitres of sarin, except Yasuo Hayashi, who carried three bags. Aum originally planned to spread the sarin as an aerosol but did not follow through with it. A single drop of sarin the size of a pinhead can kill an adult.

Carrying their packets of sarin and umbrellas with sharpened tips, the perpetrators boarded their appointed trains. At prearranged stations, the sarin packets were dropped and punctured several times with the sharpened tip of the umbrellas. The men then got off the train and exited the station to meet his accomplice with a car. By leaving the punctured packets on the floor, the sarin was allowed to leak out into the train car and stations. This sarin affected passengers, subway workers, and those who came into contact with them. Sarin is the most volatile of the nerve agents, which means that it can quickly and easily evaporate from a liquid into a vapor and spread into the environment. People can be exposed to the vapor even if they do not come in contact with the liquid form of sarin. Because it evaporates so quickly, sarin presents an immediate but short-lived threat.

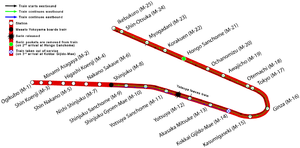

Chiyoda Line

Map of the Chiyoda Line

Map of the Chiyoda Line

The team of Ikuo Hayashi and Tomomitsu Niimi were assigned to drop and puncture two sarin packets on the Chiyoda Line. Hayashi was the perpetrator and Niimi was his get-away driver. On the way to the station, Niimi purchased newspapers to wrap the sarin packets in—the Japan Communist Party's Akahata and the Sōka Gakkai's Seikyo Shimbun. Hayashi eventually chose to use Akahata. Wearing a surgical mask commonly worn by the Japanese during cold and flu season, Hayashi boarded the first car of southwest-bound 07:48 Chiyoda Line train number A725K. As the train approached Shin-Ochanomizu Station, the central business district in Chiyoda, he punctured one of his two bags of sarin, leaving the other untouched and exited the train at Shin-Ochanomizu.

The train proceeded down the line with the punctured bag of sarin leaking until 4 stops later at Kasumigaseki Station. There, the bags were removed and eventually disposed of by station attendants, of whom two died. The train continued on to the next station where it was completely stopped, evacuated and cleaned. There were a total of 2 deaths and 231 serious injuries from this attack.

Marunouchi Line

Ogikubo-bound

Two men, Kenichi Hirose and Koichi Kitamura, were assigned to release two sarin packets on the westbound Marunouchi Line destined for Ogikubo Station. The pair left Aum headquarters in Shibuya at 6:00 am and drove to Yotsuya Station. There Hirose boarded a westbound Marunouchi Line train, then changed to a northbound JR East Saikyō Line train at Shinjuku Station and got off at Ikebukuro Station. He then bought a sports tabloid to wrap the sarin packets in and boarded the second car of Marunouchi Line train A777.

As he was about to release the sarin, however, Hirose believed the loud noises caused by the newspaper-wrapped packets had caught the attention of a schoolgirl. To avoid further suspicion, he got off the train at either Myogadani or Korakuen Station and moved to the third car instead of the second. As the train approached Ochanomizu Station, Hirose dropped the packets to the floor, repeated an Aum mantra and punctured the sarin packets with so much force that he bent the tip of his sharpened umbrella. Both packets were successfully broken, and all 900 mL of sarin was released onto the floor of the train. Hirose then departed the train at Ochanomizu and left via Kitamura's car waiting outside the station.

At Nakano-sakaue Station, 14 stops later, two severely injured passengers were carried out of the train car, while station attendant Sumio Nishimura removed the sarin packets (one of these two passengers would end up being the only fatality from this attack). The train continued on, however, with sarin still on the floor of the third car. Five stops later, at 8:38 am, the train reached Ogikubo Station, the end of the Marunouchi Line, all the while passengers boarding the train. The train continued eastbound until it was finally taken out of service at Shin-Kōenji Station two stops later. The entire ordeal resulted in one passenger's death with 358 being seriously injured.

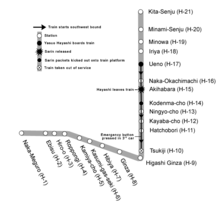

Ikebukuro-bound

Masato Yokoyama and his driver Kiyotaka Tonozaki were assigned to release sarin on the Ikebukuro-bound Marunouchi Line. On the way to Shinjuku Station, Tonozaki stopped to allow Yokoyama to buy a copy of Nihon Keizai Shimbun, the paper he would use to wrap the two sarin packets. When they arrived at the station, Yokoyama put on a wig and fake glasses and boarded the fifth car of the Ikebukuro-bound 07:39 Marunouchi Line train number B801.

As the train approached Yotsuya Station, Yokoyama began poking at the sarin packets. When the train reached the next station, he fled the scene with Tonozaki, leaving the sarin packets on the train car. The packets, however, were not fully punctured. During his drop, Yokoyama accidentally left one packet fully intact, while the other packet was only punctured once resulting in the sarin being released relatively slowly.

The train reached the end of the line, Ikebukuro, at 8:30 am where it would head back in the opposite direction. However, before it departed the train was evacuated and searched, but the searchers failed to discover the sarin packets. One passenger attributes this oversight to the fact that the search was conducted by a part-time employee instead of a full-time train assistant. Nevertheless, the train departed Ikebukuro Station at 8:32 am as the Shinjuku-bound A801. Passengers soon became ill and alerted station attendants of the sarin soaked newspapers at Kōrakuen Station. One station later, at Hongō-sanchōme, staff removed the sarin packets and mopped the floor, but the train continued on to Shinjuku. After arriving at 9:09 am, the train once again began to make its way back to Ikebukuro as the B901. The train was finally put out of service at Kokkai-gijidō-mae Station in Chiyoda at 9:27 am, one hour and forty minutes after Yokoyama punctured the sarin packet. The attack resulted in no fatalities, but over 200 people were left in serious condition.

Hibiya Line

Tōbu Dōbutsu Kōen-bound

Toru Toyoda and his driver Katsuya Takahashi were assigned to release sarin on the northeast-bound Hibiya Line. The pair, with Takahashi driving, left Aum headquarters in Shibuya at 6:30 am. After purchasing a copy of Hochi Shimbun and wrapping his two sarin packets, Toyoda arrived at Naka-Meguro Station where he boarded the first car of northeast-bound 07:59 Hibiya Line train number B711T. Sitting close to the door, he set the sarin packets on the floor. When the train arrived at the next station, Ebisu, Toyoda punctured the packets and got off the train. He was on the train for a total of two minutes, by far the quickest sarin drop out of the five attacks that day.

Two stops later, at Roppongi Station, passengers in the train's first car began to feel the effects of the sarin and began to open the windows. By Kamiyacho Station, the next stop, the passengers in the car had begun panicking. The first car was evacuated and several passengers were immediately taken to a hospital. Still, with the first car empty the train continued down the line for one more stop until it was completely evacuated at Kasumigaseki Station. This attack killed one person and seriously injured 532 others.

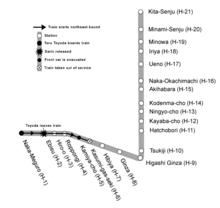

Naka-Meguro-bound

Yasuo Hayashi and Shigeo Sugimoto were the team assigned to drop sarin on the southwest-bound Hibiya Line departing Kita-Senju Station for Naka-Meguro Station. Unlike the rest of the attacks, Hayashi carried three sarin packets onto the train instead of two. Prior to the attack, Hayashi asked to carry a flawed leftover packet in addition to the two others in an apparent bid to allay suspicions and prove his loyalty to the group. After Sugimoto escorted him to Ueno Station, Hayashi boarded the third car of southwest-bound 07:43 Hibiya Line train number A720S and dropped his sarin packets to the floor. Two stops later, at Akihabara Station, he punctured the packets, left the train and arrived back at Aum headquarters with Sugimoto by 8:30 am. Hayashi made the most punctures of any of the perpetrators.

By the next stop, passengers in the third car began to feel effects from the sarin. Noticing the large, liquid soaked package on the floor and assuming it was the culprit, one passenger kicked the sarin packets out of the train and onto Kodenmachō Station's subway platform. Four people in the station died as a result.

A puddle of sarin, however, remained on the floor of the passenger car as the train continued to the next station. At 8:10 am, after the train pulled out of Hatchōbori Station, a passenger in the third car pressed the emergency stop button. The train was in a tunnel at the time, and was forced to proceed to Tsukiji Station where passengers stumbled out and collapsed on the station's platform and the train was taken out of service.

The attack was originally believed to be an explosion and was thus labeled as such in media reports. Eventually, station attendants realized that the attack was not an explosion, but rather a chemical attack. At 8:35 am, the Hibiya Line was completely shut down and all commuters were evacuated. Between the five stations affected in this attack, 8 people died and 275 were seriously injured.

Aftermath

On the day of the attack, ambulances transported 688 patients and nearly five thousand people reached hospitals by other means. Hospitals saw 5,510 patients, seventeen of whom were deemed critical, thirty-seven severe and 984 moderately ill with vision problems. Most of those reporting to hospitals were the "worried well," who had to be distinguished from those who were ill.[3]

By mid-afternoon, the mildly affected victims had recovered from vision problems and were released from hospital. Most of the remaining patients were well enough to go home the following day, and within a week only a few critical patients remained in hospital. The death toll on the day of the attack was eight that eventually rose to at least a dozen.[4]

The injured

Witnesses have said that subway entrances resembled battlefields. In many cases, the injured simply lay on the ground, many with breathing difficulties.[citation needed] Several of those affected by sarin went to work in spite of their symptoms, most of them not realizing that they had been exposed to sarin. Most of the victims sought medical treatment as the symptoms worsened and as they learned of the actual circumstances of the attacks via news broadcasts.

Several of those affected were exposed to sarin only by helping those who had been directly exposed. Among these were passengers on other trains, subway workers and health care workers. A 2008 law enacted by the Japanese government authorized payments of damages to victims of the gas attack, because the attack was directed at the government of Japan. As of December 2009, 5,259 people have applied for benefits under the law. Of those, 47 out of 70 have been certified as disabled and 1,077 of 1,163 applications for serious injuries or illnesses have been certified.[5]

Surveys of the victims (in 1998 and 2001) showed that many were still suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. In one survey, twenty percent of 837 respondents complained that they felt insecure whenever riding a train, while ten percent answered that they tried to avoid any nerve-attack related news. Over sixty percent reported chronic eyestrain and said their vision had worsened.[1]

Emergency services

Emergency services including police, fire and ambulance services were criticised for their handling of the attack and the injured, as were the media (some of whom, though present at subway entrances and filming the injured, hesitated when asked to transport victims to the hospital) and the Subway Authority, which failed to halt several of the trains despite reports of passenger injury. Health services including hospitals and health staff were also criticised: one hospital refused to admit a victim for almost an hour, and many hospitals turned victims away.

Sarin poisoning was not well known at the time, and many hospitals only received information on diagnosis and treatment because a professor at Shinshu University's school of medicine happened to see reports on television. Dr. Nobuo Yanagisawa had experience with treating sarin poisoning after the Matsumoto incident; he recognized the symptoms, had information on diagnosis and treatment collected, and led a team who sent the information to hospitals throughout Tokyo via fax.

St. Luke's Hospital at Tsukiji was one of very few hospitals in Tokyo at that time to have the entire building wired and piped for conversion into a "Field Hospital" in the event of a major disaster. This proved to be a very fortunate coincidence as the hospital was able to take in most of the 600+ victims at Tsukiji station, resulting in no fatalities at that station.

As there was a severe shortage of antidotes in Tokyo, sarin antidote stored in rural hospitals as an antidote for herbicide/insecticide poisoning were delivered to nearby Shinkansen stations, where it was collected by a Ministry of Health official on a train bound for Tokyo.

Defended by new religions scholars

In May 1995, after the sarin attack on the Tokyo subway, American scholars James R. Lewis and J. Gordon Melton flew to Japan to hold a pair of press conferences in which they announced that the chief suspect in the murders, religious group Aum Shinrikyo, couldn't have produced the sarin that the attacks had been committed with. They had determined this, Lewis said, from photos and documents provided by the group.[6]

However, the Japanese police had already discovered at Aum's main compound back in March a sophisticated chemical weapons laboratory that was capable of producing thousands of kilograms a year of the poison.[1] Later investigation showed that Aum not only created the sarin used in the subway attacks, but had committed previous chemical and biological weapons attacks, including a previous attack with sarin that had killed eight and injured 144.[7] [8]

During the Aum Shinrikyo incident Lewis and Melton's bills for travel, lodging and accommodations were paid for by Aum, according to The Washington Post.[9] Lewis openly disclosed that "Aum [...] arranged to provide all expenses [for the trip] ahead of time", but claimed that this was "so that financial considerations would not be attached to our final report".[10]

Murakami book

Popular contemporary novelist Haruki Murakami wrote Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche (1997). He was critical of the Japanese media for focusing on the sensational profiles of the attackers and ignoring the lives of the victimized average citizens. The book contains extensive interviews with the survivors in order to tell their stories. Murakami would later add a second part to the work, The Place That Was Promised, which focuses on Aum Shinrikyo.

Aum/Aleph today

Main article: Aum_Shinrikyo#Current_activitiesThe sarin attack was the most serious terrorist attack in Japan's modern history. It caused massive disruption and widespread fear in a society that had previously been perceived as virtually free of crime.

Shortly after the attack, Aum lost its status as a religious organization, and many of its assets were seized. However, the Diet (Japanese parliament) rejected a request from government officials to outlaw the group. The National Public Safety Commission received increased funding to monitor the group. In 1999, the Diet gave the commission broad powers to monitor and curtail the activities of groups that have been involved in "indiscriminate mass murder" and whose leaders are "holding strong sway over their members", a bill custom-tailored to Aum Shinrikyo.

About twenty of Aum's members, including its founder Asahara, are either standing trial or have already been convicted for crimes related to the attack. As of July 2004, eight Aum members have received death sentences for their roles in the attack.

Asahara was sentenced to death by hanging on February 27, 2004, but lawyers immediately appealed the ruling. The Tokyo High Court postponed its decision on the appeal until results were obtained from a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation, which was issued to determine whether Asahara was fit to stand trial. In February 2006, the court ruled that Asahara was indeed fit to stand trial, and on March 27, rejected the appeal against his death sentence. Japan's Supreme Court upheld this decision on September 15, 2006. (Japan does not announce dates of executions, which are by hanging, in advance of them being carried out.)

The group reportedly still has about 2,100 members, and continues to recruit new members under the name "Aleph". Though the group has renounced its violent past, it still continues to follow Asahara's spiritual teachings. Members operate several businesses, though boycotts of known Aleph-related businesses, in addition to searches, confiscations of possible evidence and picketing by protest groups, have resulted in closures.

Aum/Aleph remains on the US State Department's list of terrorist groups, but has not been linked to any further terrorist acts, nor any terrorist acts in the US. Aleph has announced a change of its policies, apologized to victims of the subway attack, and established a special compensation fund. Aum members convicted in relation to the attack or other crimes are not permitted to join the new organization, and are referred to as "ex-members" by the group.

See also

- A - a documentary film made following the arrest of the leaders of Aum Shinrikyo

- Banjawarn station

- Religion in Japan

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c CDC website, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Aum Shinrikyo: Once and Future Threat?, Kyle B. Olson, Research Planning, Inc., Arlington, Virginia

- ^ a b Asahi.com Website, Death sentences upheld for cultists

- ^ http://www.stimson.org/cbw/pdf/atxchapter3.pdf#page=25

- ^ http://www.stimson.org/cbw/pdf/atxchapter3.pdf#page=30

- ^ Sasaki, Sayo, (Kyodo News), "Aum victim keeps memory alive via film", Japan Times, March 9, 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Apologetics Index, Aum Shinrikyo, Aum Supreme Truth; Aum Shinri Kyo; Aleph, 2005

- ^ CW Terrorism Tutorial, A Brief History of Chemical Warfare, Historical Cases of CW Terrorism, Aum Shinrikyo, 2004

- ^ Matsumoto sarin victim dies 14 years after attack, Yomiuri Shimbun (August 6, 2008).

- ^ Tokyo Cult Finds an Unlikely Supporter, The Washington Post, T.R. Reid, May 1995. "The Americans said the sect had invited them to visit after they expressed concern to Aum's New York branch about religious freedom in Japan. The said their airfare, hotel bills and 'basic expenses' were paid by the cult"

- ^ Japan's Waco: Aum Shinrikyo and the Eclipse of Freedom in the Land of the Rising Sun, James R. Lewis, 1998

Bibliography

- "Survey: Subway sarin attack haunts more survivors" in Mainichi Online June 18, 2001.

- Detailed information on each subway line, including names of perpetrators, times of attack, train numbers and numbers of casualties, as well as biographical details on the perpetrators, were taken from Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche by Haruki Murakami.

- Ataxia: The Chemical and Biological Terrorism Threat and the US Response, Chapter 3 - Rethinking the Lessons of Tokyo, Henry L. Stimson Centre Report No. 35, October 2000

- Tu A. T. (2000). "Overview of sarin terrorist attacks in Japan". ACS Symposium Series 745: 304–317. doi:10.1021/bk-2000-0745.ch020.

- Ogawa Y, Yamamura Y, Ando A, et al. (2000). "An attack with sarin nerve gas on the Tokyo subway system and its effects on victims". ACS Symposium Series 745: 333–355. doi:10.1021/bk-2000-0745.ch022.

- Sidell, Frederick R. (1998). Jane's Chem-Bio Handbook 3rd edition. Jane's Information Group.

- Bonino, Stefano. Il Caso Aum Shinrikyo: Società, Religione e Terrorismo nel Giappone Contemporaneo, 2010, Edizioni Solfanelli, ISBN-978-88-89756-88-1. Preface by Erica Baffelli.

External links

- Aum Shinrikyo A history of Aum and list of Aum-related links

- The Aum Supreme Truth Terrorist Organization - The Crime library Crime Library article about Aum

- I got some pictures of sarin scattered on the metro floor Several pictures taken by One of the passengers on the scene (in Japanese)

Aum Shinrikyo Leadership Criticism Incidents Sakamoto family murder (1989) · Matsumoto incident (1994) · Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway (1995)In media UndergroundRailway accidents in 1995 Location and date Ais Gill, England (31 January) • Toronto, Canada (11 August) • Firozabad, India (20 August) • Palo Verde, AZ, United States (9 October) • Fox River, IL, United States (25 October) • Baku, Azerbaijan (28 October)

Categories:- Railway accidents in Japan

- Railway accidents in 1995

- Aum Shinrikyo

- History of Tokyo

- Terrorist incidents in 1995

- 1995 in Japan

- Terrorist incidents on railway systems

- Terrorism in Japan

- Mass murder in 1995

- Chemical weapons attacks

- Religious terrorism

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.