- Xiangqi

-

Xiangqi

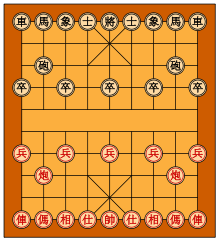

Xiangqi board with pieces in their starting positionsGenre(s) Board game Players 2 Setup time Under one minute Playing time Informal games: may vary from 20 minutes to several hours

Blitz games: up to 10 minutesRandom chance None Skill(s) required Tactics, strategy Xiangqi Chinese 象棋 Transcriptions Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin xiàngqí - Wade–Giles hsiang4-ch'i2

[ listen]

listen]Min - Hokkien POJ chhiūⁿ-kî Cantonese (Yue) - Jyutping zeong6 kei2 Xiangqi (Chinese: 象棋; pinyin: Xiàngqí) is a two-player Chinese board game in the same family as Western chess, chaturanga, shogi, Indian chess and janggi. The present-day form of Xiangqi originated in China and is therefore commonly called Chinese chess in English. Xiangqi is one of the most popular board games in China. Besides China and areas with significant ethnic Chinese communities, Xiangqi is also a popular pastime in Vietnam (Cờ tướng).

The game represents a battle between two armies, with the object of capturing the enemy's "general" piece. Distinctive features of Xiangqi include the unique movement of the pao ("cannon") piece, a rule prohibiting the generals (similar to chess kings) from facing each other directly, and the river and palace board features, which restrict the movement of some pieces.

Its Chinese name can be treated as meaning "Image Game" or "Elephant Game":

- 象 originally, and primarily, means "elephant" and is derived from a stylized drawing of an elephant; it was later used to mean "image", as a jiajie (re-use for another word which was pronounced the same); also, elephant ivory was commonly used as a material for carving models.

- 棋 means "board game".

Xiangqi contains features which are not in Indian chess: the river, the palace, and the placing of the pieces on the intersections of the lines, rather than within the squares. These features may have come from an earlier Chinese board game (perhaps a war-type game) which was also called 象棋 (Xiangqi). As in an astronomical context 象 sometimes means "constellation" or "asterism" (i.e., in both cases, a figure made of stars), there were early Chinese theorizings (which Harold James Ruthven Murray followed and believed) that the older Xiangqi simulated the movements of stars and other celestial objects in the sky.

Contents

Rules of the game

Board

Xiangqi is played on a board that is 9 lines wide by 10 lines long. In a manner similar to the game Go (Wéiqí 圍棋), the pieces are played on the intersections, which are known as points. The vertical lines are known as files, while the horizontal lines are known as ranks.

Centered at the first through third ranks of the board is a square zone also mirrored in the opponent's territory. The three point by three point zone is demarcated by two diagonal lines connecting opposite corners and intersecting at the center point. This area is known as 宮

gōng, the palace or fortress.

gōng, the palace or fortress.Dividing the two opposing sides (between the fifth and sixth ranks) is 河 hé, the river. The river is often marked with the phrases 楚河

chǔ hé, meaning "Chu River", and 漢界 (in Traditional Chinese).

chǔ hé, meaning "Chu River", and 漢界 (in Traditional Chinese).  hàn jiè, meaning "Han border", a reference to the Chu-Han War. Although the river provides a visual division between the two sides, only a few pieces are affected by its presence: "soldier" pieces have an enhanced move after crossing the river, while "elephant" pieces cannot cross.

hàn jiè, meaning "Han border", a reference to the Chu-Han War. Although the river provides a visual division between the two sides, only a few pieces are affected by its presence: "soldier" pieces have an enhanced move after crossing the river, while "elephant" pieces cannot cross.The starting points of the soldiers and cannons are typically marked with small crosses, but not all boards have these marks.

Play

The pieces start in the position shown in the diagram above. Which player moves first has varied throughout history, and also varies from one part of China to another. Some Xiangqi books state that the black side moves first;[citation needed] others state that the red side moves first. Also, some books may refer to the two sides as north and south; which direction corresponds to which color also varies from source to source. Generally, red goes first in most modern formal tournaments.[1]

Each player in turn moves one piece from the point it occupies to another point. Generally pieces are not permitted to move through a point occupied by another piece. A piece can be moved onto a point occupied by an enemy piece, in which case the enemy piece is "captured" and removed from the board. A player cannot capture one of his own pieces. Pieces are never "promoted" (converted into other pieces), although the pawn/soldier is able to move sideways after it crosses the river.

Generally all pieces capture using their normal moves. One piece has a special capture move, as described below.

The game ends when one player captures the other's general. When the general is in danger of being captured by the enemy player on his next move, the enemy player is said to have "delivered a check" (simplified Chinese: 照将/将军; traditional Chinese: 照將/將軍, abbreviated (simplified Chinese: 将; traditional Chinese: 將; pinyin: jiāng

jiāng)) and the general is said to be "in check". A check should be announced. If the general's player can make no move to prevent the general's capture, the situation is called "checkmate" (simplified Chinese: 将死; traditional Chinese: 將死).

jiāng)) and the general is said to be "in check". A check should be announced. If the general's player can make no move to prevent the general's capture, the situation is called "checkmate" (simplified Chinese: 将死; traditional Chinese: 將死).Unlike Chess, in which a stalemate is a draw, in Xiangqi, a player with no legal moves left loses. In Xiangqi, a player (often with material or positional disadvantage) may attempt to check or chase pieces in a way that the moves fall in a cycle, forcing the opponent to draw the game. The following special rules are used to make it harder to draw the game by endless checking and chasing (regardless of whether the positions of the pieces are repeated or not):

- The side that perpetually checks with one piece or several pieces will be ruled to lose under any circumstances unless he or she stops the perpetual checking.

- The side that perpetually chases any one unprotected piece with one or more pieces will be ruled to lose under any circumstances unless he or she stops the perpetual chasing. Chases by generals and soldiers are allowed however.[2]

- If one side perpetually checks and the other side perpetually chases, the perpetually checking side has to stop or be ruled to lose.

- When neither side violates the rules and both persist in not making an alternate move, the game can be ruled as a draw.

- When both sides violate the same rule at the same time and both persist in not making an alternate move, the game can be ruled as a draw.

Different sets of rules set different limits on what is considered "perpetual". For example, Club Xiangqi rules allow a player to check/chase six consecutive times using one piece, twelve times using two pieces, and eighteen times using three pieces before considering the check/chase a perpetual check/chase.[2]

The above rules to prevent perpetual checking and chasing are popular, but they are by no means the only rules. There are a large number of confusing end game situations.[3]

Pieces

The pieces are flat circular disks, each with a Chinese character on, sometimes engraved into the surface. The black pieces are marked with somewhat different characters from the corresponding red pieces; this practice may have originated in situations where there was only one material available to make the pieces from and no coloring material available to distinguish the opposing armies.

General

The generals are labelled with the Chinese character 將 (trad.) / 将 (simp.)

jiàng (general) on the black side and 帥 (trad.) / 帅 (simp.)

jiàng (general) on the black side and 帥 (trad.) / 帅 (simp.)  shuài (marshal) on the red side.

shuài (marshal) on the red side.The general starts the game at the midpoint of the back edge (within the palace). The general may move and capture one point either vertically or horizontally, but not diagonally. The two generals may not face each other in the same file with no intervening pieces.

If that happens, the "flying general" (飛將) move may be executed, in which one general may "fly" across the board to capture the enemy general. In practice this rule is only used to enforce checkmate. The general may not leave the palace except when executing the "flying general" move.

The Indian name "king" for this piece was changed to "general" because China's rulers objected to their royal title "king" or "emperor" being given to a game-piece.[4]

Advisor

The advisors (also known as guards or ministers, and less commonly as assistants, mandarins, or warriors) are labelled 士

shì ("scholar", "gentleman", "officer") for black and 仕

shì ("scholar", "gentleman", "officer") for black and 仕  shì ("scholar", "official") for red. Rarely, sets use the character 士 for both colours.

shì ("scholar", "official") for red. Rarely, sets use the character 士 for both colours.The advisors start to the sides of the general. They move and capture one point diagonally and may not leave the palace, which confines them to five points on the board. They serve to protect the general.

The advisor is probably derived from the mantri in Chaturanga, like the queen in Western chess.

Elephant

The elephants are labeled 象 xiàng (elephant) for black and 相 xiàng (minister) for red. They are located next to the advisors. These pieces move and capture exactly two points diagonally and may not jump over intervening pieces (the move is described as being like the character 田 Tián [field]). If an elephant is blocked by an intervening piece, it is known as "blocking the elephant's eye"[dubious ] (塞象眼). They may not cross the river; thus, they serve as defensive pieces.

Because an elephant's movement is thus restricted to just seven board positions, it can be easily trapped or threatened. Typically the two elephants will be used to defend each other.

The Chinese characters for "minister" and "elephant" are homophones (

Listen) and both have alternative meanings as "appearance" or "image". However, both are referred to as elephants in the game.

Listen) and both have alternative meanings as "appearance" or "image". However, both are referred to as elephants in the game.Horse

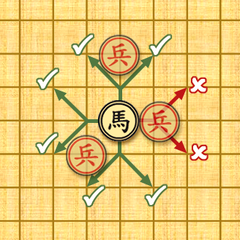

The horses are labelled 馬

mǎ for black and 傌

mǎ for black and 傌  mà for red in sets marked with Traditional Chinese characters and 马 mǎ for both black and red in sets marked with Simplified Chinese characters. Some traditional sets use 馬 for both colours. They begin the game next to the elephants. A horse moves and captures one point vertically or horizontally and then one point diagonally away from its former position, a move which is traditionally described as being like the character 日 Rì. The horse does not jump as the knight does in Western chess. Thus, if there were a piece lying on a point one point away horizontally or vertically from the horse, then the horse's path of movement is blocked and it is unable to move in that direction. Note, however, that a piece two points away horizontally or vertically or a piece a single point away diagonally would not impede the movement of the horse. Blocking a horse is also known as "hobbling the horse's leg" (蹩馬腿). The diagram on the left illustrates the horse's movement.

mà for red in sets marked with Traditional Chinese characters and 马 mǎ for both black and red in sets marked with Simplified Chinese characters. Some traditional sets use 馬 for both colours. They begin the game next to the elephants. A horse moves and captures one point vertically or horizontally and then one point diagonally away from its former position, a move which is traditionally described as being like the character 日 Rì. The horse does not jump as the knight does in Western chess. Thus, if there were a piece lying on a point one point away horizontally or vertically from the horse, then the horse's path of movement is blocked and it is unable to move in that direction. Note, however, that a piece two points away horizontally or vertically or a piece a single point away diagonally would not impede the movement of the horse. Blocking a horse is also known as "hobbling the horse's leg" (蹩馬腿). The diagram on the left illustrates the horse's movement.Since horses can be blocked, it is sometimes possible to trap the opponent's horse. It is possible for one player's horse to attack the opponent's horse while the opponent's horse is blocked from attacking, as seen in the diagram on the right.

Chariot

The chariots are labelled 車 for black and 俥 for red in sets marked with Traditional Chinese characters and 车 for both black and red in sets marked with Simplified Chinese characters. Some traditional sets use 車 for both colors. All of these characters are pronounced as

jū. The chariot moves and captures vertically and horizontally any distance, and may not jump over intervening pieces. The chariots begin the game on the points at the corners of the board. The chariot is considered to be the strongest piece in the game.

jū. The chariot moves and captures vertically and horizontally any distance, and may not jump over intervening pieces. The chariots begin the game on the points at the corners of the board. The chariot is considered to be the strongest piece in the game.The chariot is sometimes known as the "rook" by English speaking players, since it is like the rook in Western chess. Chinese players (and others) often call this piece a "car", since that is one modern meaning of the character 車.

Cannon

The long-range threat of the cannon

The long-range threat of the cannon

The cannons are labelled 砲

pào for black and 炮 pào for red. They are homophones. Sometimes 炮 is used for both red and black.

pào for black and 炮 pào for red. They are homophones. Sometimes 炮 is used for both red and black.砲 pào means a "catapult" for hurling boulders. 炮 pào means "cannon". The 石 shì radical of 砲 means 'stone', and the 火 huǒ radical of 炮 means 'fire'. However, both are normally referred to as cannons in English.

In Xiangqi, each player has two cannons. The cannons start on the row behind the soldiers, two points in front of the horses. Cannons move like the chariots, horizontally and vertically, but capture by jumping exactly one piece (whether it is friendly or enemy) over to its target. When capturing, the cannon is moved to the point of the captured piece. The cannon may not jump over intervening pieces if not capturing another piece, nor may it capture without jumping. The piece which the cannon jumps over is called the 炮臺 (trad.) / 炮台 (simp.) pào tái ("cannon platform"). Any number of unoccupied spaces may exist between the cannon and the cannon platform, or between the cannon platform and the piece to be captured, including no spaces (the pieces being adjacent) in both cases. Cannons are powerful pieces at the beginning of the game when platforms are plentiful, and are used frequently in combination with chariots to achieve checkmate. Although cannons can be exchanged for a horse immediately from their starting positions, this is usually not favorable, in part due to the superiority of cannons over horses at the beginning of the game. The two cannons, when used together, can form a check that cannot be stopped easily. As they line up in the attack against the opposing general, the back cannon checks the general while the front cannon, serving as the platform, prohibits blocking for the opposing side. The opposing side can only move the general, capture the back cannon, or block between the two cannons.

Soldier

Each side has five soldiers, labelled 卒

zú (pawn/private) for black and 兵

zú (pawn/private) for black and 兵  bīng (soldier) for red. Soldiers are placed on alternating points, one row back from the edge of the river. They move and capture by advancing one point. Once they have crossed the river, they may also move (and capture) one point horizontally. Soldiers cannot move backward, and therefore cannot retreat; however, they may still move sideways at the enemy's edge.

bīng (soldier) for red. Soldiers are placed on alternating points, one row back from the edge of the river. They move and capture by advancing one point. Once they have crossed the river, they may also move (and capture) one point horizontally. Soldiers cannot move backward, and therefore cannot retreat; however, they may still move sideways at the enemy's edge.The soldier is sometimes known as the "pawn" by English speaking players, since it is similar to that piece in Western chess.

Approximate relative values of the pieces

Piece Point(s)  Soldier before crossing the river

Soldier before crossing the river1  Soldier after crossing the river

Soldier after crossing the river2–3  Advisor

Advisor2  Elephant

Elephant2  Horse

Horse4.5  Cannon

Cannon5  Chariot

Chariot9–10 These approximate values do not take into account positional advantages. For example, the chariot at the corner in the beginning of the game is not very useful, but it can be moved to points where it affects the game much more, for example near the center of the board or the opponent's palace. Also, the value of a cannon drops as the game goes on due to having fewer platforms for use in capturing, while the value of the horse increases slightly due to fewer obstructions. Although the chariot has the highest value of 9–10 points, players will often in certain game scenarios value a cannon or horse at or more than the level of a chariot due to the cannon's unique attack style. What is left on the board is also important to the value of a piece. For example, in a mid or late game, if red still has two chariots and black has one advisor left, that advisor is very valuable for black because it is very easy for red to checkmate with two chariots if black does not have an advisor.

Equipment

One player's pieces are usually painted red (or, less commonly, white), and the other player's pieces are usually painted black (or, less commonly, blue or green).

Xiangqi pieces are represented by disks marked with a Chinese character identifying the piece and painted in a colour identifying which player the piece belongs. In mainland China, most sets still use traditional Chinese characters (as opposed to simplified Chinese characters) for the pieces. Modern pieces are usually made of plastic, though some sets use pieces made of wood, and more expensive sets may use pieces made of jade. In more ancient times, many sets were simple unpainted woodcarvings; thus, to distinguish between the pieces of the two sides, most corresponding pieces use characters that are similar but vary slightly between the two sides.

The oldest Xiangqi piece found to date is a 俥 (chariot) piece. It is kept in the Henan Provincial Museum.

Notation

There are several types of notation used to record Xiangqi games. In each case the moves are numbered and written with the same general pattern.

- (first move) (first response)

- (second move) (second response)

It is clearer but not required to write each move pair on a separate line.

Notational system 1

The book The Chess of China[5] describes a move notation in which the ranks of the board are numbered 1 to 10 from closest to farthest away, followed by a digit 1 to 9 for files from right to left. Both values are relative to the moving player. Moves are then indicated as follows:

[piece name] ([former rank][former file])-[new rank][new file]Thus, the most common opening in the game would be written as:

- 炮 (32)–35, 馬 (18)–37

Notational system 2

A notational system partially described in A Manual of Chinese Chess[6] and used by several computer software implementations describes moves in relative terms as follows:

[single-letter piece abbreviation][former file][operator indicating direction of movement][new file, or in the case of purely vertical movement, number of ranks traversed]The file numbers are counted from each player's right to each player's left.

In case there are two identical pieces in one file, symbols + (front) and – (rear) are used instead of former file number. Direction of movement is indicated via an operator symbol. A plus sign is used to indicate forward movement. A minus sign or hyphen is used to indicate backwards movement. A dot or period or equal sign is used to indicate horizontal or lateral movement. If a piece (such as the horse or elephant) simultaneously moves both vertically and horizontally, then the plus or minus sign is used rather than the period.

Thus, the most common opening in the game would be written as:

- C2.5 H8+7

The single letter piece abbreviations are

Piece Initial(s)  Advisor

AdvisorA  Cannon

CannonC  Chariot

ChariotR*  Elephant

ElephantE  General

GeneralG  Horse

HorseH  Soldier

SoldierS *for Rook, because using C would conflict with the letter for Cannon

Notational system 3 (unofficial, for players of Western chess)

Letters are used for files and numbers for ranks. File "a" is on Red's left and rank "1" is nearest to Red. A point's designation does not depend on which player moves; for both sides "a1" is the lowest left point from Red's side.

[single-letter piece abbreviation][former position][capture indication][new position][check indication][analysis]Pieces are abbreviated as for system 2, except that no letter is used for the soldier.

Former position is only indicated if necessary to distinguish between two identical pieces that could have made the move. If they share the same file, indicate which rank moves; if they share the same rank, indicate which file moves. If they share neither rank or file then the file is indicated.

Capture is indicated by "x". No letter is used to indicate a non-capturing move.

Check is indicated by "+", double check by "++", triple check by "+++", and quadruple check by "++++". Checkmate is indicated by "#".

For analysis purposes, bad moves are indicated by "?" and good moves by "!". These can be combined if the analysis is uncertain ("!?" might be either but is probably good; "?!" is probably bad) or repeated for emphasis ("??" is a disaster).

Thus, the most common opening in the game would be written as:

- Che3 Hg8

An example of a brief game ("the early checkmate") is:

Gameplay

Because of the size of the board and the low number of long-range pieces, there is a tendency for the battle to focus on a particular area of the board.

Tactics

There are several tactics common to games in the chess family, including Xiangqi. Some common ones are briefly discussed here; see Chess tactics for more details.

- Fork: When one enemy piece can attack more than one piece, they are forked.

- Pin: A piece is pinned when it cannot be moved without exposing a more important piece to be captured. A cannon can pin two pieces at once on one file or rank, and unlike in Western chess, because the horse can be blocked it can pin pieces as well.

- Skewer: A piece is skewered when it is attacked and, on moving, exposes a less important piece to be captured.

Fork Pin Skewer 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h i The horse forks the soldier and the chariot.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h i The cannon is pinned by the chariot.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h i The chariot is skewering the general and chariot. When the general moves, the chariot can be taken.

- Discovered check: A discovered check occurs when an attacking piece moves so that it unblocks a line for a chariot, cannon, and less often, the horse, to check the enemy general. The piece uncovering the check can safely move anywhere within its powers regardless of whether the opponent has those squares under protection.

- Double check: A double check occurs when two pieces simultaneously threaten the enemy general. It may or may not be possible to block. An example of a double check that can be blocked is a chariot checking the general and acting as a platform for a cannon situated behind. This can be blocked by moving a piece between the general and the chariot, blocking the cannon's fire and that of the chariot as well. An example of a double check that can not be blocked is a horse between the enemy general and a chariot. The horse can move to check the general and uncover a check from the chariot. No piece can block because there is an attack from two directions, and both can't be blocked at once. In either case, capturing one of the checking pieces doesn't get the general out of check either. Sometimes a double check results in mate. Another, blockable, case of double check is when a cannon or chariot uncovers two checks at once from two horses, but it is rare.

- Particular to Xiangqi is triple check, which arises with a cannon, a chariot, and a horse or a chariot and two horses, the latter being comparatively rare. In the first case the horse moves to give check uncovering a double check from the chariot and the cannon, which uses the chariot as a platform. This check can't be blocked and capturing a checking piece doesn't work either, as that would leave the general still in check from two enemy pieces. In the second case the chariot moves to give check uncovering a double check from the two horses. Quadruple check is also possible, arising with 2 horses, a chariot, and a cannon.

Triple check Quadruple check Triple check, alternate position 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h i Red's horse has moved from e5 to d7, giving check and exposing a double check from chariot and cannon.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h i Red's chariot has moved from f9 to e9, giving check and exposing a triple check from cannon and both horses.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h i Red's chariot discovers two checks from the horses and gives check itself.

Use of pieces

Usually, the soldiers do not support each other unless the player has no better move. This is because from the initial position, it takes a minimum of 5 moves of a soldier to allow twin soldiers to protect each other.

The two chariots are not normally lined up together as they are the most powerful pieces and in doing so, a player risks losing one chariot to an inferior piece of the enemy. Depending on the situation, it may be advantageous to position a chariot at one of the corners of the enemy's side of the board, where it is very difficult to dislodge, and threatens the enemy general.

It is common to use the cannons independently to control particular ranks and files. Using a cannon to control the middle file is often considered vital strategy, because it helps to lock certain pieces such as the advisors and elephants in certain positions to prevent a check. The two files adjacent to the middle file are also considered important and horses and chariots can be used to push for checkmate here.

The two cannons on the same file is also a powerful formation. For example, the rear cannon threatens the general. Moving a piece in front of the cannons to block the attack does not work, because then the front cannon will attack the general.

A common defensive configuration is to leave the general at its starting position, deploy one advisor and one elephant on the two points directly in front of the general, and to leave the other advisor and the other elephant in their starting positions, to the side of the general. In this setup, the paired-up advisors and elephants support each other, and the general is immune from attacks by cannons. However, with the loss of a single advisor or elephant, the general becomes vulnerable to cannons, and this setup may need to be abandoned. The defender may move advisors or elephants away from the general, or even sacrifice them intentionally, to ward off attack by a cannon.

Openings

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h i The most common opening pair of moves

Since the left and right flank of the starting setup are symmetrical and therefore equivalent, it is customary to always make the first move from the right flank. Starting on the left flank is considered to be needlessly confusing.

The most common opening is to move the cannon to the central column, an opening known as 當頭炮 (trad.) / 当头炮 (simp.) dāng tóu pào = "appropriate start cannon". The most common reply is to advance the horse on the same flank. Together, this move-and-response is known by the rhyme 當頭炮,馬來跳 (trad.) / 当头炮,马来跳 (simp.)

dāng tóu pào, mǎ lái tiào. The notation for this is "1. 炮 (32)–35, 馬 (18)–37" or "1. C2.5 H8+7". See also the diagrams to the right.

dāng tóu pào, mǎ lái tiào. The notation for this is "1. 炮 (32)–35, 馬 (18)–37" or "1. C2.5 H8+7". See also the diagrams to the right.This is usually followed by the most common second move, 出車 (trad.) / 出车 (simp.) chū jū—"chariot sortie"—in which the first player moves a chariot forward one space (usually the right one – moving the left one loses the horse, and even if the defender manages to trap the cannon with his/her chariots, the cannon can simply take the nearest advisor resulting in a net gain of an advisor in material for the other side and the maneuver to trap the cannon loses time allowing the opponent to bring out other pieces).

The most common reply is to move the right advisor diagonally. 上士 shàng shì. This is to prevent a series of events that leads to the first player quickly checkmating the second.

Less common first moves include:

- moving an elephant to the central column

- advancing the soldier on the third or seventh file

- moving a horse forward

- moving either cannon behind the 2nd soldier from the left or right

General advice for the opening includes rapid development of at least one chariot, because it is the most powerful piece and the only long-range piece besides the cannon. There is a saying that only a poor player does not move a chariot in the first three moves. It may not be a bad move to develop one horse to the edge of the board, for example, to avoid being blocked by one of one's own soldiers that cannot advance. Usually, at least one horse should be moved to the middle.

History

Xiangqi has a long history. Its ancestor is believed to be the Indian chess game of Chaturanga,[7] though its precise origins have not yet been definitely confirmed; there are some indications that the game may have been played as early as the third century BC, during the Warring States Period. (See chess in early literature and timeline of chess.) Judging by its rules, Xiangqi was apparently closely related to military strategy in ancient China. The ancient Chinese game of Liubo may have had an influence as well.

References to a game called Xiangqi date back to the Warring States Period; according to the first century BC text, Shuo yuan (說宛), it was one of Lord Mengchang of Qi's interests.[8] Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou once wrote a book Xiang Jing in AD 569. It is believed to have described the rules of an astronomically themed game called Xiangqi or Xiangxi (象戲). The word Xiàngqí 象棋 is usually translated as "elephant game" or "figure game", because the Chinese character 象 means "elephant" and "figure"; it originated as a stylized drawing of an elephant, and was used also to write a word meaning "figure", likely because the two words were pronounced the same. But the name can also be treated as meaning "constellation game", and sometimes the xiàngqí board's "river" is called the "heavenly river", which may mean the Milky Way. For these reasons, Harold James Ruthven Murray, author of A History of Chess, theorized that "in China it [Chess] took over the board and name of a game called 象棋 in the sense of "Constellation Game" (rendered by Murray as "Astronomical Game"), which represented the apparent movements of naked-eye-visible astronomical objects in the night sky, and that the earliest Chinese references to 象棋 meant the Astronomical Game and not Chinese chess". previous games called xiàngqí may have been based on the movements of sky objects. However, the connection between 象 and astronomy is marginal, and arose from constellations being called merely "figures" in astronomical contexts where other meanings of "figure" were less likely; this usage may have led some ancient Chinese authors to theorize that the game 象棋 started as a simulation of astronomy.

To support his argument, Murray quoted an old Chinese source that says that in that older Xiangqi (which modern Xiangqi may have taken some of its rules from) the game-pieces could be shuffled, which does not happen in chess-type Xiangqi as known now.[9] Murray also wrote that in ancient China there was more than one game called Xiangqi.[10]

An alternative hypothesis to Murray's is that Xiangqi was patterned after the array of troops in the Warring States era. David H. Li, for example, argues that the game was developed by Han Xin in the winter of 204 BC-203 BC to prepare for an upcoming battle.[11] His theories have been questioned by other chess researchers, however.[12]

The earliest description of the game's rules appears in the story "Cen Shun" (岑順) in the collection Xuanguai lu (玄怪錄), written in the middle part of the Tang dynasty.

With the economic and cultural development during the Qing Dynasty, Xiangqi entered a new stage. Many different schools of circles and players came into prominence. With the popularization of Xiangqi, many books and manuals on the techniques of playing the game were published. They played an important role in popularizing Xiangqi and improving the techniques of play in modern times.

A Western-style Encyclopedia of Chinese Chess Openings was not written until 2004.

Modern play

Tournaments and leagues

Although Xiangqi has its origin in Asia, there are Xiangqi leagues and clubs all over the world. Each European nation generally has its own governing league; for example, in Britain, Xiangqi is regulated by the United Kingdom Chinese Chess Association. Asian countries also have nationwide leagues, such as the Malaysia Chinese Chess Association in Malaysia.

In addition, there are also several international federations and tournaments. For example, the Chinese Xiangqi Association hosts several tournaments every year, including the Yin Li and Ram Cup Tournaments.[13] Other organizations include the Asian Xiangqi Federation[14] and a World Xiangqi Federation,[15] which hosts tournaments and competitions bi-annually, though most are limited to players from member nations.

Rankings

The Asian Xiangqi Federation and its corresponding member associations also rank players in a number format similar to the rankings of chess. The best player in China, according to the 2006 Chinese National Ratings, was Xu Yinchuan with a rating of 2628.[16] Other strong players include Lu Qin and Hu Ronghua.

The Asian Xiangqi Federation also bestows the title of grandmaster to select individuals around the world who have excelled at Xiangqi or have made special contributions to the game. Though there are no specific criteria for becoming a grandmaster, the list of grandmasters is limited to fewer than a hundred people.[17]

Computers

The game-tree complexity of Xiangqi is approximately 10150, so in 2004 it was projected that a human top player will be defeated before 2010.[18]

And in the Computer-Human Xiangqi Dual Meet in 2006, the final score was Computer 5.5 – Human 4.5

Xiangqi is one of the more popular competitions at the annual Computer Olympiad.

Computer programs for playing Xiangqi show the same development trend as has occurred for international Chess: they are usually console applications (called engines) which communicate their moves in text form through some standard protocol. For displaying the board graphically, they then rely on a separate Graphical User Interface. Through such standardization, many different engines can be used through the same GUI, and the GUI can also be used for automated play of different engines against each other. Popular protocols are UCI (Universal Chess Interface), UCCI (Universal Chinese Chess Interface), Qianhong (QH) protocol, and WinBoard/XBoard (WB) protocol (the latter two named after the GUIs that implemented them). There now exist many dozens of Xiangqi engines supporting one or more of these protocols, including some commercial engines.

Computer Xiangqi Programs

Xiangqi Graphical User Interfaces

- Qianhong Xiangqi [25] (QH, and UCCI through adapter)

- WinBoard / XBoard [26] (WB, and QH, UCI, UCCI through adapters)

- XQ Wizzard [27] (UCCI, and QH through adapter)

Computer Xiangqi Website

- With many engine downloads [28] (Chinese site, but worth the effort of translation!)

Computer Xiangqi Servers

Variations

Using a standard Xiangqi board and pieces

- Blitz Chess

- Each player only has around 5–10 minutes each (depending on rules), leading to a fast-paced game with little or no room for thought, and moves have to be made by instinct.[citation needed]

- Supply Chess

- Similar to the Western chess variant, Bughouse Chess, this variant features the ability to re-deploy captured pieces, similar to a rule in Shogi, Four players play two games side-by-side with a team of two playing against another team. One teammate plays black and other plays red. Any piece obtained by capturing the opponent's piece is given to the teammate for use in the other game. These pieces can be deployed by the teammate to give him an advantage over the other player, so long as the piece starts on the player's own side of the board and does not cause the opponent to be in check.

- Formation

- One player's pieces are jumbled up, then placed randomly on one side of the river, except for the generals and advisors which must be at their usual positions in normal Xiangqi, and elephants must start at two of the seven points that they could reach from their usual positions. The other player's pieces are set up to mirror the first's. All other rules are the same as in Xiangqi.

- Blind Chess

- More well known in Hong Kong than in mainland China, this game uses Xiangqi's pieces and board, but does not follow any of its rules, bearing more of a resemblance to the western game Stratego as well as the Chinese gameLuzhanqi. The game is played on only half the Xianqi board, turned sideways to allow nine rows and five columns. Players flip their pieces so that the characters are concealed from their opponent, and then arrange them on their respective ends of the board. At each turn, a player can do one of three things: They may choose to uncover a concealed piece, move one of their own pieces to an empty square (pieces can only move to an adjacent square and not diagonally regardless of its movement style in original Xiangqi), or they may choose to capture one of their opponents pieces. There are limitations for the last option however: Each piece has a "rank" that enables it to capture pieces beneath its rank when an enemy piece is directly next to it. In the Taiwanese version, the rank of pieces (from highest to lowest) is: 1. General. 2. Advisor. 3. Elephant. 4. Chariot. 5. Horse. 6. Cannon. 7. Soldier. In Hong Kong, the rank is: 1. General. 2. Chariot. 3. Horse. 4. Cannon. 5. Elephant. 6. Advisor. 7. Soldier. In either version the Soldier is the lowest rank, but also important as it is the only piece that can capture the enemy General. A special rule enables the cannon to capture the same way as it does in Xiangqi by jumping over exactly one piece (whether friend or foe) landing on its target. Because of this rule, although by rank the cannon is higher than soldier, it cannot capture a soldier even when the soldier is placed directly next to it. The game continues until one of the players has lost all of his pieces. Blind chess is mostly a game of luck as the player cannot choose where his pieces are set up; he can only increase his chances by moving pieces and uncovering appropriately, calculating the odds that the uncovered piece next to them can be friend or foe, superior or inferior. T

Using a special board and/or pieces

There are many versions of three-player Xiangqi, or "San Xiangqui" (Three Elephants Game), all played on special boards:

- San Guo Qi

- "The Game of Three Kingdoms" is played on a special hexagonal board with three armies (red, blue and green) of Xiangqi pieces vying for dominance. A Y-shaped river trisects the board into three gem-shaped territories, each containing the grid found on one side of a Xiangqi board, but distorted to make the game playable by three people. Each player has 18 pieces: the classical 16 of regular Xiangqi and 2 new ones which stand on the same file as the Cannons. The new pieces have different names depending on their side: Fire (Huo), for red, Flag (Qi) for blue, Wind (Feng) for green, and they move two spaces orthogonally, and then one diagonally. The Generals each bear the name of the historical Chinese kingdoms—Shu for red, Wei for blue, Wu for green—from China's Three Kingdoms Period.[34] It is likely that San Guo Qi first appeared under the Southern Song Dynasty (960–1279).[35]

- San You Qi

- "Three Friends Chess" was invented by Zheng Jinde from Shexian in Anhui province during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor of Qing Dynasty (1661–1722). It is played on a Y-shaped board with a full army of Ziangqi pieces set up at the end of each of the board's three wide radii. In the center of the board sits a triangular zone with certain features (ocean, mountain, city walls) each of which are impassible by certain pieces. Two of an army's five Soldiers are replaced by new pieces called "Fires", which move one diagonal space forward. On the front corners of the palace are positioned two "Flag" pieces, which move two spaces forward inside their own camp, and then one space in any direction inside an enemy camp.[35]

'Sanrenqi:"Three Men Chess" is a riverless commercial variant played on a cross-shaped board with some special rules, including a fourth, neutral country called Han. Han has three Chariots, one Cannon, and one General named "Emperor Xian of Han," but these pieces do not move and do not belong to any of the three players until a certain point in the game when two player team up against the third player, who also gets to control Han (similar to player playing their own hand, plus that of a dummy in Bridge.[35]

- Si Guo Qi

- "Four Kingdoms Chess" is also played on a riverless, cross-shaped board, but with four players. Because there are no rivers, elephants may move about the board freely.[35]

See also

- Board game

- China Qiyuan

- Culture of China

- History of games

- List of world championships in mind sports

- Mind sport

- National Peasants' Games

- Xiang Jing

- Xiangqi at the 2007 Asian Indoor Games

- Xiangqi at the 2009 Asian Indoor Games

- Xiangqi at the 2010 Asian Games

- World Mind Sports Games

References

- ^ Xiangqi: Chinese Chess at chessvariants.com

- ^ a b Chinese Chess Rules at clubxiangqi.com

- ^ Asian Chinese Chess Rules at clubxiangqi.com

- ^ A History of Chess, p.120, footnote 3 says that Ssŭ-ma Kuang wrote in T'ung-kien nun in AD 1084 that Emperor Wen of Sui (541–604) found at an inn some foreigners playing a board game whose pieces included a piece called "I pai ti" = "white emperor"; in anger at this misuse of his title he had everybody at the inn put to death.

- ^ Leventhal, Dennis A. The Chess of China. Taipei, Taiwan: Mei Ya, 1978. (getCITED.org listing)

- ^ Wilkes, Charles Fred. A Manual of Chinese Chess. 1952.

- ^ Henry Davidson, A Short History of Chess, p. 6

- ^ "Facts on the Origin of Chinese Chess". Banaschak.net. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ A History of Chess, p.122, footnote 12: "In the biography of Lü-Ts'ai. The Emperor T'ai-Tsung (627–650) was puzzled by the phrase 太子洗馬 t'ai-tze-si-ma ('the crown-prince washes the horses') in the 周武帝三局象經 Zhou Wudi sanju xiangjing ('Zhou Wudi's three games in the Xiangjing'): 'to wash the dominoes' means 'to shuffle them' in modern Chinese; ma or 'horse' is used for the pieces in a game. The phrase probably meant 'the crown-prince shuffles the men'). He consulted Yün-Kung, who had known the phrase as a young man but had forgotten it, and then Lü-Ts'ai. The latter, after a night's consideration, explained the point, and recovered the method of play of the astronomical game and the actual position."

- ^ A History of Chess, p.122: The 32nd book of the history of the T'ang dynasty (618–907) said that Wu-Ti wrote and expounded a book named San-kü-siang-king (Manual of the three xiangqi's).

- ^ This theory is propounded in The Genealogy of Chess

- ^ "A story well told is not necessarily true – being a critical assessment of David H. Li's "The Genealogy of Chess", by Peter Banaschak. Banaschak.net. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ From FAQ #21: “What are some of the top tournaments in the world?”, rec.games.chinese-chess, chessvariants.com

- ^ Asian Xiangqi Federation homepage includes English translations of Asian tournament results, rules, etc.

- ^ World Xiangqi Federation. Wxf.org. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ 职业棋手等级分-象棋资料-象棋网[dead link]

- ^ rec.games.chinese-chess FAQ lists the International Grandmasters by country.

- ^ Yen, Chen, Yang, Hsu, 2004, Computer Chinese Chess.

- ^ Chinese Chess Soul Chinese Chess Computer Software

- ^ NEU Chess. NEU Chess. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ XieXie. Cc-xiexie.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ XQ Master

- ^ Hidden Lynx – A free Chinese Chess program for Windows

- ^ HOXChess – A cross platform, open source Xiangqi program. Hoxchess.googlecode.com (2010-03-25). Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ Qianhong Xiangqi. Jcraner.com (2009-04-01). Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ WinBoard Xiangqi. Home.hccnet.nl. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ Xiangqi Wizard. Sourceforge.net. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ 象棋巫师 – 最受欢迎的中国象棋单机版游戏 – 象棋百科全书. Xqbase.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ Vietson Online Chinese Chess. Vietson.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ ThaiGB – An Internet Chinese Chess server in Thai. Thaibg.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ Ajax Chinese Chess – Play Chinese Chess online!. Ajaxchess.pragmaticlogic.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ Club Xiangqi – A Chinese Chess server with English/Vietnamese/Chinese interface. Clubxiangqi.com (2007-12-22). Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ PlayXiangqi – A Xiangqi server with Open Source client and Open Server API. Playxiangqi.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-01.

- ^ "The Chess Variants Pages". The Game of the Three Kingdoms. http://www.chessvariants.com/xiangqivariants.dir/chin3pl.html. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Sanguo Qi (Three Kingdoms Chess) & Sanyou Qi (Three Friends Chess)". Another view on Chess: Odyssey of Chess. http://history.chess.free.fr/sanguoqi.htm. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

Further reading

- Lau, H. T. Chinese Chess. Tuttle Publishing, Boston, 1985. ISBN 0-8048-3508-X.

- Leventhal, Dennis A. The Chess of China. Taipei, Taiwan: Mei Ya, 1978. (out-of-print but can be partly downloaded)

- Li, David H. First Syllabus on Xiangqi: Chinese Chess 1. Premier Publishing, Bethesda, Maryland, 1996. ISBN 0-9637852-5-7.

- Li, David H. The Genealogy of Chess. Premier Publishing, Bethesda, Maryland, 1998. ISBN 0-9637852-2-2.

- Li, David H. Xiangqi Syllabus on Cannon: Chinese Chess 2. Premier Publishing, Bethesda, Maryland, 1998. ISBN 0-9637852-7-3.

- Li, David H. Xiangqi Syllabus on Elephant: Chinese Chess 3. Premier Publishing, Bethesda, Maryland, 2000. ISBN 0-9637852-0-6.

- Li, David H. Xiangqi Syllabus on Pawn: Chinese Chess 4. Premier Publishing, Bethesda, Maryland, 2002. ISBN 0-9711690-1-2.

- Li, David H. Xiangqi Syllabus on Horse: Chinese Chess 5. Premier Publishing, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004. ISBN 0-9711690-2-0.

- Sloan, Sam. Chinese Chess for Beginners. Ishi Press International, San Rafael, Tokyo, 1989. ISBN 0-923891-11-0.

- Wilkes, Charles Fred. A Manual of Chinese Chess. 1952.

- Lo, Andrew; Wang, Tzi-Cheng. "'The Earthworms Tame the Dragon': The Game of Xiangqi" in Asian Games, The Art of Contest, edited by Asia Society, 2004. (a serious and updated reading about Xiangqi history)

External links

Learn

- Rules, openings, strategy, ancient manuals

- An Introduction to Xiangqi for Chess Players

- Presentation, rules, history and variants of xiangqi

- Xiangqi: Chinese Chess at the Chess Variant Pages

- Apertures and strategy In Spanish

Play

- PlayOK -Play Xiangqi online, free!

- XiangQi on ChessFreaks, play online or on your mobile

- Vietson Online Chinese Chess / Xiangqi – Play with friends from all over the world

- Play Xiangqi online against human or robot opponents, free!

- Club Xiangqi – Play Chinese Chess online with or without a user fee

- PlayXiangqi – A free online service with Open Source client and Open Server API

Software

Categories:- Xiangqi

- Abstract strategy games

- Traditional board games

- Chess variants

- Chess in China

- Chinese games

- Chinese words and phrases

- Chinese ancient games

- Mind sports

- Board games

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.