- Leonard Matlovich

-

Leonard P. Matlovich

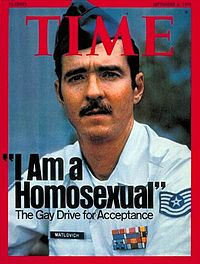

Matlovich on the cover of Time magazineBorn July 6, 1943

Savannah, Georgia, U.S.Died June 22, 1988 (aged 44)

West Hollywood, California, U.S.Buried at Congressional Cemetery,

Washington, D.C.Allegiance United States of America Service/branch United States Air Force Years of service 1963-1975 Rank Technical Sergeant Battles/wars Vietnam War Awards Bronze Star Medal

Purple Heart

Air Force Commendation MedalOther work Gay rights activist Technical Sergeant Leonard P. Matlovich (July 6, 1943 – June 22, 1988)[1] was a Vietnam War veteran, race relations instructor, and recipient of the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star.[2]

Matlovich was the first gay service member to fight the ban on gays in the military, and perhaps the best-known gay man in America in the 1970s next to Harvey Milk. His fight to stay in the United States Air Force after coming out of the closet became a cause célèbre around which the gay community rallied. His case resulted in articles in newspapers and magazines throughout the country, numerous television interviews, and a television movie on NBC. His photograph appeared on the cover of the September 8, 1975, issue of Time magazine, making him a symbol for thousands of gay and lesbian servicemembers and gay people generally.[3][4][5][6] Matlovich was the first openly gay person to appear on the cover of a U.S. newsmagazine.[7] According to author Randy Shilts, "It marked the first time the young gay movement had made the cover of a major newsweekly. To a movement still struggling for legitimacy, the event was a major turning point." [8] In October 2006, Matlovich was honored by LGBT History Month as a leader in the history of the LGBT community.

Contents

Early life and early career

Born in Savannah, Georgia, he was the only son of a career Air Force sergeant. He spent his childhood living on military bases, primarily throughout the southern United States. Matlovich and his sister were raised in the Roman Catholic Church. Not long after he enlisted at 19, the United States increased military action in Vietnam, about ten years after the French had abandoned active colonial rule there. Matlovich volunteered for service in Vietnam and served three tours of duty. He was seriously wounded when he stepped on a land mine in Đà Nẵng.

While stationed in Florida near Fort Walton Beach, he began frequenting gay bars in nearby Pensacola. "I met a bank president, a gas station attendant - they were all homosexual," Matlovich commented in a later interview. When he was 30, he slept with another man for the first time. He "came out" to his friends, but continued to conceal the fact from his commanding officer. Having realized that the racism he'd grown up around was wrong, he volunteered to teach Air Force Race Relations classes, which had been created after several racial incidents in the military in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He became so successful that the Air Force sent him around the country to coach other instructors. Matlovich gradually came to believe that the discrimination faced by gays was similar to that faced by African Americans.

Activism

In March 1974, previously unaware of the organized gay movement, he read an interview in the Air Force Times with gay activist Frank Kameny who had counseled several gays in the military over the years. He called Kameny in Washington DC and learned that Kameny had long been looking for a gay service member with a perfect record to create a test case to challenge the military's ban on gays. Four months later, he met with Kameny at the longtime activist's Washington DC home. After several months of discussion with Kameny and ACLU attorney David Addlestone during which they formulated a plan, he hand-delivered a letter to his Langley AFB commanding officer on March 6, 1975. When his commander asked, "What does this mean?" Matlovich replied, "It means Brown versus the Board of Education" - a reference to the 1954 landmark Supreme Court case outlawing racial segregation in public schools.[9]

Perhaps the most painful aspect of the whole experience for Matlovich was his revelation to his parents. He told his mother by telephone. She was so stunned she refused to tell Matlovich's father. Her first reaction was that God was punishing her for something she had done, even if her Roman Catholic faith would have not sanctioned that notion. Then, she imagined that her son had not prayed enough or had not seen enough psychiatrists. She later admitted that she had suspected the truth for a long time. His father finally found out by reading it in the newspaper, after his challenge became public knowledge on Memorial Day 1975 through an article on the front page of The New York Times and that evening's CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. Matlovich recalled, "He cried for about two hours." After that, he told his wife that, "If he can take it, I can take it."

Discharge and lawsuit

At that time, the Air Force had a unique exception clause that technically could allow gays to continue to serve under undefined circumstances. During his September 1975 administrative discharge hearing, an Air Force attorney asked him if he would sign a document pledging to "never practice homosexuality again" in exchange for being allowed to remain in the Air Force. Matlovich refused. Despite his exemplary military record, tours of duty in Vietnam, and high performance evaluations, the panel ruled Matlovich unfit for service and he was recommended for a General, or Less than Honorable, discharge. The base commander recommended that it be upgraded to Honorable and the Secretary of the Air Force agreed, confirming Matlovich's discharge in October 1975.

He sued for reinstatement, but the legal process was a long one, with the case moving back and forth between United States District and Circuit Courts. When, by September 1980, the Air Force had failed to provide US District Court Judge Gerhard Gesell an explanation of why Matlovich did not meet their criteria for exception (which by then had been eliminated but still could have applied to him), Gesell ordered him reinstated into the Air Force and promoted. The Air Force offered Matlovich a financial settlement instead, and convinced they would find some other reason to discharge him if he reentered the service, or the conservative US Supreme Court would rule against him should the Air Force appeal, Matlovich accepted. The figure, based on back pay, future pay, and pension was $160,000.

Excommunication

A converted Mormon and church elder when he lived in Hampton, Virginia, Matlovich found himself at odds with the Latter Day Saints and their opposition to homosexual behavior: he was twice excommunicated by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for homosexual acts. He was first excommunicated on October 7, 1975, in Norfolk, Virginia, and then again January 17, 1979, after his appearance on the Phil Donahue television show in 1978, without being rebaptized. But, by this time, Matlovich had stopped being a believer at all.[7]

Settlement, later life and illness

From the moment his case was revealed to the public, he was repeatedly called upon by gay groups to help them with fund raising and advocating against anti-gay discrimination, helping lead campaigns against Anita Bryant's effort in Miami, Florida, to overturn a gay nondiscrimination ordinance and John Briggs' attempt to ban gay teachers in California. Sometimes he was criticized by individuals more to the left than he had become. “I think many gays are forced into liberal camps only because that’s where they can find the kind of support they need to function in society" Matlovich once noted. After being discharged, he moved from Virginia to Washington, D.C., and, in 1978, to San Francisco. In 1981, he moved to the Russian River town of Guerneville where he used the proceeds of his settlement to open a pizza restaurant.

Matlovich's grave at the Congressional Cemetery.

Matlovich's grave at the Congressional Cemetery.

The tombstone reads:

"A Gay Vietnam Veteran

When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one"

Photographer: Michael Bedwell

Original web source: http://www.leonardmatlovich.comWith the outbreak of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. in the late 1970s, Leonard's personal life was caught up in the virus’ hysteria that peaked in the 1980s. He sold his Guerneville restaurant in 1984, moving to Europe for a few months. He returned briefly to Washington, D.C., in 1985 and, then, to San Francisco where he sold Ford cars and once again became heavily involved in gay rights causes and the fight for adequate HIV-AIDS education and treatment.

During the summer of 1986, Matlovich felt fatigued, then contracted a prolonged chest cold he seemed unable to shake. When he finally saw a physician in September of that year, he was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. Too weak to continue his work at the Ford dealership, he was among the first to receive AZT treatments, but his prognosis was not encouraging. He went on disability and became a champion for HIV/AIDS research for the disease which was claiming tens of thousands of lives in the Bay Area and nationally. He announced on Good Morning America in 1987 that he had contracted HIV, and was arrested with other demonstrators in front of the White House that June protesting what they believed was an inadequate response to HIV-AIDS by the administration of President Ronald Reagan.

Death

On June 22, 1988, less than a month before his 45th birthday, Matlovich died of complications from HIV/AIDS[1] beneath a large photo of Martin Luther King, Jr. His tombstone, meant to be a memorial to all gay veterans, does not bear his name. It reads, “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.” Matlovich's tombstone at Congressional Cemetery is on the same row as that of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

Legacy

Not long after Matlovich's death in 1988, his estate donated his personal papers and memorabilia to the GLBT Historical Society, a museum, archives and research center in San Francisco.[10] The society has featured Matlovich's story in two exhibitions: "Out Ranks: GLBT Military Service From World War II to the Iraq War," which opened in June 2007 at the society's South of Market gallery space, and "Our Vast Queer Past: Celebrating San Francisco's GLBT History," which opened in January 2011 at the society's new GLBT History Museum in the Castro District.[11][12][13]

In addition, San Francisco resident Michael Bedwell has created a website in honor of Matlovich and other gay U.S. veterans. The site includes a history of the ban on gays in the U.S. military both before and after its transformation into Don't Ask, Don't Tell, and illustrates the role that gay veterans fighting the ban played in the earliest development of the gay rights movement in the United States.[14]

Literature and film

- Castañeda, Laura and Susan B. Campbell. "No Longer Silent: Sgt. Leonard Matlovich and Col. Margarethe Cammermeyer." In News and Sexuality: Media Portraits of Diversity, 198-200. Sage, 2005, ISBN 1412909996.

- Hippler, Mike. Matlovich: The Good Soldier, Alyson Publications Inc., 1989, ISBN 1-55583-129-X

- Miller, Neil. "Leonard Matlovich: A Soldier's Story." In Out of the Past: Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the Present, 411-414. Virginia: Vintage Books, 1995, ISBN 0679749888

- Shilts, Randy. Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the US Military, Diane Publishing Company, 1993, ISBN 0-78815-416-8

- Sergeant Matlovich vs. the U.S. Air Force, made-for-television dramatization directed by Paul Leaf, written by John McGreevey. Originally aired on NBC, August 21, 1978.

References

- ^ a b "GAY ACTIVIST LEONARD MATLOVICH, 44, IS BURIED WITH FULL MILITARY". Chicago Tribune (Tribune Company). July 3, 1988. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/24801118.html?dids=24801118:24801118&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Jul+03%2C+1988&author=&pub=Chicago+Tribune+%28pre-1997+Fulltext%29&desc=GAY+ACTIVIST+LEONARD+MATLOVICH%2C+44%2C+IS+BURIED+WITH+FULL+MILITARY&pqatl=google. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ Books.google.com

- ^ "I Am a Homosexual" TIME Magazine (September 8, 1975)

- ^ Steve Kornacki (2010-12-01). "The Air Force vs. the "practicing homosexual"". Salon.com. http://www.salon.com/news/politics/war_room/2010/12/01/matlovich_dadt. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ^ Matthew S. Bajko (2010-12-01). "Friends plan plaque for gay Castro vet". Bay Area Reporter. http://www.ebar.com/news/article.php?sec=news&article=3069. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ^ Servicemembers United. "The DADT Digital Archive Project". Servicemembers United. http://dadtarchive.org/?page_id=61. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ^ a b Leonard Matlovich Makes Time

- ^ Randy Shilts (1993). Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the U.S. Military. Macmillan. p. 227. http://books.google.com/books?id=iOAmL6JPCE0C&pg=PA227&lpg=PA228&dq=matlovich+time+cover+shilts&source=bl&ots=mtvGulQjh5&sig=Rv6Wh5ZpaXmUtxBy6ojAhpEHuqE&hl=en&ei=sC_jTdf-Lufm0QGyif2sBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBsQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- ^ "The Sergeant v. the Air Force" TIME Magazine (September 8, 1975).

- ^ GLBT Historical Society. "Guide to the Leonard Matlovich Papers, 1961-1988 (Bulk 1975-1988)"] (Collection No. 1988-01); retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ GLBT Historical Society (2007). Out Ranks website; retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Leff, Lisa (2007-06-16). "Exhibit puts history of gay veterans on view," Army Times (Associated Press); retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Ming, Dan (2011-01-13). "Visit the nations's first queer museum," The Bay Citizen; retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ "About this site," at LeonardMatlovich.com; retrieved 2011-10-30.

External links

- Official website

- Leonard Matlovich at Find a Grave

- GLBT Historical Society (San Francisco); holds the personal papers and memorabilia of Leonard Matlovich (Collection No. 1988-01)

- Honor Roll: Gay Veterans Gather To Honor those Who Served Metro Weekly (November 9, 2006)

- "Leonard Matlovich" glbthistorymonth.org (October 7, 2006)

- Exhibit puts history of gay veterans on view Army Times (June 16, 2007)

- Gay Veterans Gather to Honor Their Own Washington Post (November 12, 2008)

- Leonard Matlovich at the Internet Movie Database

Categories:- 1943 births

- 1988 deaths

- American activists

- United States Air Force airmen

- American military personnel of the Vietnam War

- American military personnel discharged for homosexuality

- American LGBT military personnel

- Homosexuality and Mormonism

- People excommunicated by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- AIDS-related deaths in California

- Burials at the Congressional Cemetery

- Recipients of the Bronze Star Medal

- Recipients of the Purple Heart medal

- American people of Croatian descent

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.