- Garum

-

Garum, similar to liquamen,[1] was a type of fermented fish sauce condiment that was an essential flavour in Ancient Roman cooking, the supreme condiment.[2]

Although it enjoyed its greatest popularity in the Roman world,[3] it originally came from the Greeks, gaining its name from the Greek words garos or garon (γάρον), which named the fish whose intestines were originally used in the condiment's production.

Contents

Roman diet

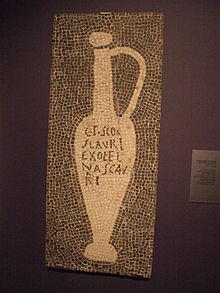

For the Romans it was both a staple to the common diet and a luxury for the wealthy. After the liquid garum was ladled off of the top of the mixture, the remains of the fish, called allec, was used by the poorest classes to flavour their staple porridge. Among the rich, the best garum fetched prices for which the historian of food Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat found no parallel in caviar but rather with the precious essences used in perfumery.[4] Garum appears in most of the recipes featured in Apicius, a Roman cookbook, which also offers a technique to render palatable garum that had gone bad. The sauce was generally made through the crushing and fermentation in brine of the innards of various fishes such as mackerel,[5] tuna, eel, and others. While the finished product was apparently mild and subtle in flavor—the nobile garum of Martial's epigram[6]—the actual production of garum created such unpleasant smells as to become relegated to the outskirts of cities so that the neighbors would not be offended by the odour.

When mixed with wine (oenogarum, a popular Byzantine sauce), vinegar, black pepper, or oil, garum was served to enhance the flavor of a wide variety of dishes, including boiled veal and steamed mussels, even pear-and-honey soufflé. Diluted with water (hydrogarum) it was distributed to Roman legions. Pliny remarked that it could be diluted to the colour of honey wine and drunk;[7] as such a tonic, garum was also employed as a medicine—ancient Romans considered it to be one of the best cures available for many ailments, including dog bites, dysentery, and ulcers; additionally, it was used as an ingredient in cosmetics and for removal of unwanted hair and freckles. Garum was thought to ease chronic diarrhea and treat constipation.[8]

Garum was prepared from the intestines of small fishes, macerated in salt and cured in the sun for one to three months, where the mixture fermented and liquified in the dry warmth, the salt inhibiting the common agents of decay. The end product was very nutritious, retaining a high amount of protein and amino acids, along with a good deal of minerals and B vitamins.[8] According to archaeologist Timmy Gambin, garum also contained monosodium glutamate, making it an appetizing, addictive food additive.[9] It was common for fishermen to lay out their catch according to the type and part of the fish. This allowed makers to pick the exact ingredients they wanted.[10] Concentrated decoctions of aromatic herbs, varying according to the locale, were added—sometimes from in-house gardens.[10] A fine strainer was inserted into the fermenting vessel and the thick liquid was ladled out.

The manufacture and export of garum was an element of the prosperity of coastal Greek emporia from the Ligurian coast of Gaul to the coast of Hispania Baetica, and, Toussaint-Samat observes, an impetus for Roman penetration of these coastal regions.[11] Amphorae recovered from shipwreck sites off Ansérune and Agde bear the traces of the garum they contained and date as early as the fifth century BC. Umbricius Scaurus' production of garum put the ancient city of Pompeii on the map. The factories where garum was produced in Pompeii have not been found yet, which has led many researchers to believe that the factories lay outside the walls of the city. Each port had its own traditional recipe, but by the time of Augustus Romans considered the best to be garum from Cartagena and Gades in Baetica—garum sociorum, "garum of the allies".[11]

Seneca, holding the old-fashioned line against the expensive craze, cautioned against it, even though his family was of Baetian Corduba:

Do you not realize that garum sociorum, that expensive bloody mass of decayed fish, consumes the stomach with its salted putrefaction?—Seneca, Epistle 95.Today one can still see a garum factory at the Baetian site of Baelo Claudia in present-day Tarifa and Carteia in present-day San Roque in Spain. This Spanish garum was an export to Rome, and gained the towns a certain amount of prestige in their day. The garum of Lusitania (present-day Portugal) was also highly prized in Rome. It was shipped to Rome directly from the harbour of Lacobriga (present-day Lagos). A former Roman garum factory can be visited in the Baixa area of central Lisbon.[12] Fossae Marianae, located on the Southern tip of present day France, served as a distribution hub for Western Europe, including Gaul, Germania and to Britain.[13]

In 2008, archaeologists used the residue from garum found in containers in Pompeii to confirm the August date of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, by detecting that it was made entirely of bogues, fish that congregate in the summer months.[14]

See also

References

- ^ "Liquamen is an enigma. It was in the first century A.D. a sauce distinct from garum (Cf CIL IV passim) but by the fifth century A.D., at the latest, the term came to refer to garum" (Robert I. Curtis, "In Defense of Garum" The Classical Journal 78.3 (February–March 1983, pp. 232-240) p. 233 note 8).

- ^ (R. Zahn), Real-Encyclopaedia der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, s.v. "Garum", 1st Series 7 (1912) pp. 841-849.

- ^ As with garlic in modern times, not every Roman was addicted to garum: aside from Seneca (see below), Martial congratulates a friend on keeping up amorous advances to a girl who had indulged in six helpings of it, and a surviving fragment of Plato Comicus spoke of "putrid garum", noted by Robert I. Curtis, "In Defense of Garum" The Classical Journal 78.3 (February–March 1983, pp. 232-240) p. 232; Curtis notes the modern change in Western taste effected by familiarity with the Vietnamese nuoc-mam.

- ^ Toussaint-Samat, The History of Food, revised ed. 2009, p. 338f.

- ^ Robert Curtis (Curtis 1983) showed that in most surviving tituli picti inscribed on amphorae, where the fish ingredient is shown, the fish is mackerel.

- ^ Martial, Epigrams 13.

- ^ Pliny, Historia Naturalis 13.93.

- ^ a b Curtis, Robert I. (1984) "Salted Fish Products in Ancient Medicine". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, XXXIX, 4:430-445.

- ^ "Lost Ships of Rome". Secrets of the Dead. PBS. http://video.pbs.org/video/1645539777#.

- ^ a b Curtis, Rober I. 1979. The Garum Shop of Pompeii. Cronache Pompeiane. XXXI. 94. p5-23.

- ^ a b Toussaint-Samat (2009).

- ^ Fundação Millennium bcp Fundação Millennium bcp - Núcleo Arqueológico

- ^ Curtis, Robert I. 1988. Spanish Trade in Salted Fish Products in the 1st and 2nd Centuries A.D. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration. XXXIX. 205-210.

- ^ Lorenzi, Rossella Fish Sauce Used to Date Pompeii Eruption

Further reading

- Butterworth, Alex and Ray Laurence. Pompeii: The Living City. New York, St. Martin's Press, 2005.

- McCann, A.M. (1994). "The Roman Port of Cosa",(273 BC), Scientific American, Ancient Cities, pp. 92–99, by Anna Marguerite McCann. Covers: modifying harbor, for the garum industry, amphora factory, hydraulic concrete, of "Pozzolana mortar" and the five piers, of the Cosa harbor, the lighthouse on pier 5, diagrams, and photographs. Height of Port city: 100 BC. For: Garum Industry at port of Cosa, Italy, 273 BC.'

- Atik, S. "Marcus Gavius Apicius ve Garum" III-IV. Ulusal Arkeolojik Arastirmalar Sempozyumu, Anadolu / Anatolia Ek Dizi No. 2 / Suppl. Series No. 2, 15–25, Ankara, 2008.

External links

- James Grout: Garum, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

Fish sauce Anchovy essence • Bagoong monamon • Bagoong terong • Budu • Cincalok • Garum • Gentleman's Relish • Mahyawa • Marie Rose sauce • Padaek • Pissalat • Pla ra • Prahok • Shottsuru • Shrimp paste • Worcestershire sauce • XO sauceCategories:- Fish sauce

- Fermented foods

- Roman cuisine

- Umami enhancers

- Fish products

- Ancient Greek cuisine

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.