- Culture of Póvoa de Varzim

-

The culture of Póvoa de Varzim, in Portugal, deriving from the different working classes and with influences arriving from the maritime route from Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean Sea is ancient and culturally unique. The most charismatic of its communities, formerly overwhelmingly dominant, is the fisher community. It is one of Portugal's oldest fishing outposts. As it occurs in other old fisher communities around the world, the Povoan one has distinct cultural traits and a strong local identity.[1][2]

The expression Ala-Arriba means "(upwards) strength" and it represents the co-operation between the inhabitants and is also seen as the motto of Póvoa de Varzim. The docudrama film Ala-Arriba!, by José Leitão de Barros, popularized this unique Portuguese fishing community within the country during the 1940s and Povoan maritime culture was used by Salazar regime as a stereotype for all Portuguese. Several fishing communities in Portugal, Brazil and Portuguese-speaking Africa were influenced or started by Povoan fishermen.

Contents

Identity and ethnicity

Póvoa de Varzim is an ethno-cultural entity.[1] Until the beginning of the 20th century, the communities of Póvoa de Varzim were marked by endogamy, exclusiveness and local identity features with several centuries.[2]

Due to endogamy and a caste system, the fisher community of Póvoa de Varzim kept particular ethnic features. Povoan fishermen, supported by 19th century scientific theories, believed they were a separate race, named "Raça Poveira" (Povoan Race). Anthropological and cultural data indicate the colonization of Nordic fishermen during the period of the coast's resettling. Since the 19th century, the visible ethnic differences when comparing with the surrounding people, led to different theories over the origin of the population: Suebi, Prussians, Teutons, Normans and even Phoenicians. In the book The Races of Europe (1939), Povoans were considered to be slightly blonder than average, with wide faces of unknown origin and robust cheeks.[3] In a research published in O Poveiro (1908), using 19th century scientific methodology, the anthropologist Fonseca Cardoso considered that an anthropological element, most noticeably the aquiline nose, was of semitic-Phoenician origin. He considered that Povoans were the result of a mixture of Phoenicians, Teutons, Jews and, mostly, Normans.[4]

Baptista de Lima disagreed with the Phoenician theory stating Povoans are not Phoenicians, as those did not brought their colonization here.[5] Although Punic visits and extensive trade is proven by the significant archaeological findings of Carthaginian vases in the Castro city of Terroso. Óscar Fangueiro noticed that the Nordic influence could have happened during the late Middle Ages when Portugal built diplomatic ties with Denmark.[6]

Ramalho Ortigão when he wrote about Póvoa in the book "As Praias de Portugal" (1876), The Beaches of Portugal, stated that the main curiosity of Póvoa was the Povoan fishermen, that was a special "race" in the Portuguese coastline; completely different from the Mediterranean type typical of Ovar and Olhão, Povoans are of "Saxon" type: they are "redheaded, clear eyes, wide shoulders, athletic chest, herculean legs and arms, round and strong faces."[5]

The local popular expressions "Poveirinhos pela graça de Deus" (Little Povoans by the grace of God) and "Reino da Póvoa" (Kingdom of Póvoa) trace their origin to a maritime trip by King Luis I of Portugal when the king's ship, near the coast, saw a lancha poveira boat. The king was surprised with the distinct looks of the boat's crew and asked them if they were Spanish, the king's supposition shocked Povoans and the crew said they weren't Spanish. Then the king asks if they were Portuguese, and the Povoans replied once more they were not, they said they were "(Little) Povoans by the grace of God". Then the king asks from which kingdom they come from, they replied they were from the Kingdom of Póvoa.[5]

The Povoan fishermen only married with peoples that were part of its fisher caste, and only within its community in Póvoa de Varzim or small ancient fishing villages directly related with Póvoa, namely Santo André (currently in the modern civil parishes of Aguçadoura and Aver-o-Mar) and Fão (in Esposende). Since the 18th century, the urban expansion of Póvoa de Varzim to the south, created the new fishing communities of Poça da Barca and Caxinas in the municipality of Vila do Conde. As such, the ethnicity was used to justify the annexation of these areas, even during the Estado Novo regime. Currently, the "Raça Poveira" expression is mostly used in football to describe perseverance and courage.[7]

Along with the fishermen, there were also the Galician farmers, these were ancient peoples and typical Northern Portuguese from the Minho region were Póvoa is located. These also contributed to the identity of Póvoa de Varzim with traditions such as Masseira farm fields and the Povoan cart, the Carroça Poveira. But both communities, despite sharing the same land, lived isolated from each other, mostly due to the fishermen rules. Óscar Fangueiro, author of Sete Séculos na Vida dos Poveiros (Seven centuries in the Life of Povoans) contradicted the fisher endogamous theory. In his study he noticed Póvoa had immigration since very early periods and noticed that some farmers were integrated in the fisher community.[6]

Immigration from Galicia to Póvoa de Varzim is ancient. There are notable Povoans with Spanish Galician ancestry. The Povoan surname "Nova" is believed to be derived from Galician "Nóvoa". With the development of fishery and, in more recent periods, beach therapy, Póvoa got even more immigration, to such an extent that the city had regional bonds stretching from Galicia, Minho, Alto Douro, Trás-os-Montes and Beira Alta provinces.[8]

The 20th century brought significant changes due to the popularization of beach tourism with several people from Northern Portugal, chiefly from Guimarães and Famalicão, moving to the city. Some Povoan fishing settlements were established in the Portuguese overseas provinces in Africa in the beginning of the 20th century and with the independence of these countries in late 1970s, Póvoa became one of the main Portuguese cities to where the African Portuguese headed, thus this event had particular impact in the city. In the end of the century, there's observable immigration from Eastern Europe, China, Brazil and Angola.

Traditional society

Structure

Formerly the population was divided into different "castes": The Lanchões (those who possessed boats that were capable of deep-water fishing, thus more prosperous); the Rasqueiros (the fisher "bourgeoisie" that used "rasca" nets to fish ray, lobster and crabs) and the Sardinheiros or Fanaqueiros (those who possessed small boats and could only catch fish of smaller size along the shore) and, isolated from them, the Lavradores (the farmers). There were also the communities, who joined both ways of living, the Sargaceiros (sargassum seaweed gatherers, used as a fertilizer in farm fields) and the seareiros (who fished small common and unwanted "pilado" crabs to fertilize fields).

As a rule, the communities remained distinct, and mixed marriages between the different communities were forbidden, mostly because of the isolationism of the fishermen who were headed by a group of patriarchs. With the urban development at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, this caste structure is today only part of the past.[9][10]

Values

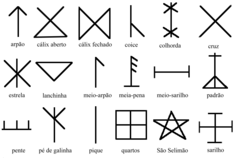

Octávio Filgueiras noticed that "Appeared in Galicia boats and fishermen arriving from the north, after the critical period of the Viking and Norman raids" and "one of the most important features is the cultural unity of these fisher communities that used primitive ships". Filgueiras noticed that the use of family marks was one of the most distinctive traits of that cultural unity. This use occurred in Povoan and Danish fishermen but also in the Baltic, in the area of Dantzig. The similarity of siglas poveiras and the runic characters show immediate associations.[11]

The traditional casamento poveiro (Povoan marriage), in which the newly-wed couple was covered by a fisherman's net and watered with vinho verde in order to bring fortune to the marriage, is becoming a forgotten practice. In Póvoa's tradition (that persists to the present day), the heir of the family is the youngest son (as in old Brittany and Denmark).[12] The younger son is the heir because it was expected that he would take care of his parents when they became old. Also, unlike the rest of the nation, it is the woman who governs and leads the family – this matriarchy is derived from the fact that the man was usually fishing at sea.[13]

Saints stoning

In the 19th century, a Povoan religious practice chocked the overwhelming catholic country. In a 1868 magazine it is told that: "It is said, for a long time in Minho [Region], that the fishermen of Póvoa de Varzim were so superstitious, that the women when there were storms, and wanting to beg to their favorite saint or saints to free their husbands boats from the gorging ocean, they said absurd and extravagant blasphemies, like a savage people could do in front of the most ridiculous idols."[8]

The author stated: "For this reason it is told that the women of the people, in dire straits, walked to the chapel of Saint Joseph, and in there, they stoned the saint, of such devotion to them, saying: "Wake up Saint Joseph, Wake up! You sh... saint Take care of my husband, or my son, Saint Joseph!"[8]

And continued: "What is correct is that not only the women of Bairro de S.José district, but also the ones from Bairro da Lapa, that in a moment of overwhelming anxiety, when the angry and raging waves brought to the beach a cadaver in each surf; in those moments, the poor women revel the pain that tormented them and went to the sand grounds and the ocean with a sad outcry and painful praying."[8]

Mythology

Sea legends

The fishermen, who traveled to Newfoundland fishing cod, told stories of Eskimo women in loved by Povoan fishermen, shipwrecks, the visits to Saint John's and lost boats in the middle of the ocean, half true and half legend.[14] The fishermen of the region are known to fish in Newfoundland since 1506.[6]

The Peixe grande or the "Big Fish" was the name that Povoans gave to a gigantic sea creature. In the holly days and Sundays the fishermen didn't go to work at sea because of a story concerning a Corpus Christi celebration when Póvoa de Varzim got numerous visitors due to that religious festival. Seeing several potential costumers, the fishermen went to work at sea, and their boat got filled with the best fish. The happy fishermen sailed back to Póvoa. Meanwhile, they noticed Peixe grande going after them, and the mestre (captain of the boat) saw it as a divine punishment and the fishermen to defend themselves from the creature, threw the fisheries to the water, and while docking and with no caught fish left, they kissed the sand and never more the Povoan fishermen went to the sea in holly days.

Cape Santo André (Saint Andrew Cape), a place that shows evidence of Romanization and of probable earlier importance, was known in Classical Latin as Promontorium Avarus and in Ancient Greek as Auaron akron (Αὔαρον ἄκρον), a name of Celt origin. It is of ancient cult in Póvoa, and was common to see groups of fishermen, with a light in the hand, in pilgrimage to the Cape's chapel in the last evening of November. They believed Saint Andre fisher fished, from the depths, the souls of the drowned ones and those who did not visited Santo André in life they would have to go there as a cadaver.[15] Near the cape, there's a rock with dips that the people believe are the footprints of Saint Andrew. It is known that in the great shipwreck of 1892, several bodies were found near the cape.

Supernatural beings in town

The most common stories are the ones related to the Povoan witch (bruxa), some were evil, named Bruxas do Diabo (Devil witches) and others who weren't responsible for their condition. Witches lived amongst the population, especially in the streets of Ramalhão and Norte, and was possible that a witch's husband was not aware that his wife was a witch.

The witches fate (fado das bruxas) was that, by night, they left their homes and followed the Devil throw the streets. By going throw the streets, the witches caused damages to the inhabitants belongings, they lifted the boat's oars, they opened the farmer's casks and caused other kinds of torments. The magical and protected use of the Sanselimão sigla, a pentagram, is associated to the witches. The use of the sigla poveira had several purposes, such as protection by saving a witch from her fate. To save her, a steel Sanselimão should be held in hand, another sanselimão should be drawn in the ground in the street were one would, during the night, wait the Devil to go throw the street with the witches behind him. The witch, one's wife, stretched her hand to be pulled by her husband to the area inside the sanselimão drawn in the ground. The other witches would torment the man, swearing and whistling.

The Bezerro maldito or the "Damned Calf" was a damned bull or calf that walked throw the streets of Póvoa, and the people in their homes listened to the sound of its paws while walking throw the street. In Póvoa there was no cattle, these only existed in the surrounding villages. Tia Desterra, a notable local story teller, always listened to these stories while a child, she saw it in a windy Summer evening. She said he was black and white, and when the calf walked throw, there was so much wind that it twisted.

The legend of the Grande Cobra or the "Big Snake" is refereed in 1758, and is related with the devotion of Lady of Varzim (Senhora de Varzim), a 13th century icon that appeared miraculously in the area of Largo das Dores (old town's square), and the old Matriz church of Póvoa de Varzim, a 11th century Romanesque-Gothic temple located in the same square, an area known to be populated by venomous reptiles, especially the Grande Cobra.

Fonte da Bica fountain, the early water source for the city center, was a place in which the people believed the Devil appeared during Friday nights with the full moon. It was also known to help single girls to get married. North of town, Moura Encantada Fountain, or Castro Fountain is a pre-Roman fountain related to the Moura, a Celtic water deity, witches, and a golden Bullock cart.

Accent

The Povoan accent known as Falar poveiro (Povoan speech), Sotaque poveiro (Povoan accent) or simply Poveiro, occasionally erroneously called caxineiro, is part of the Portuguese dialect known by linguists as Interâmnico and, popularly, as Nortenho or Northern Portuguese, which is the oldest dialect of the Portuguese language and it is spoken in Coastal Northern Portugal from Viana do Castelo to Porto and, inland, it reaches Braga. The region is the birthplace of the Portuguese language. There are two subdialects: Porto-Póvoa and Braga-Viana, each of these subdialects is further divided into Porto, Póvoa, Braga, and Viana. The Póvoa one is the transitional dialect between the speeches of Braga and Porto.

Despite sharing numerous features found in other Northern Portuguese accents, the Povoan accent has particular features and includes influences from the region of Beira, in Central Portugal, that are not found in other Northern Portuguese accents, as in the pronunciation in connected speech as in os olhos which is spoken as [oʒɔʎoʃ] instead of [ozɔʎoʃ]. A distinctive feature of the accent, common in the fisher community, is the extensive use of open vowels where standard Portuguese uses closed or nasal vowels: it occurs in words ending with /a/, as in batata ([batatɛ] instead of [bɐtatɐ]); in the plural form, batatas, it is pronounced as [batatɨʃ] or [batatɛʃ]. Amanhã (tomorrow) is pronunced as [amɛɲa], instead of [ɐ̃mɐɲɐ̃]. Currently, the urban population often pronounce it as [amɐɲa]. "Ão" termination is always pronounced as [aɲ] as in cão ([kaɲ] which can pronounced as [kɔɲ] in other Northern Portuguese accents and as [kɐ̃ũ] in Standard Portuguese.

Similarly to Galician, "ch" is pronounced as [tʃ] instead of [ʃ]. Fizeste (you did) can be pronounced as [fizɛtʃɨʃ], although [fizɛʃtɨʃ] or is today much more common and Falou-lhe([fɐlowʎɨ]), he spoke to him/her, is pronounced as "falou-le" ([falowlɨ]), the same situation occurs with others verbs. Eu fui (I went) can be pronounced as "eu foi"; intestino (intestine) can be pronounced as "indestino" and vomitar (to vomite) can be pronounced as "gomitar".

Povoan vocabulary includes Tarrote (sparrow) instead of pardal; estonar (to peel) instead of descascar; "chopa" or "chó" (girl) instead of rapariga; trumpeteiro or "tropeteiro" (mosquito) instead of mosquito or melga; gano (branch) instead of galho, bouça is referred to a forest with bushes. Dinner or lunch are often referred to as o comer and prezigo refers to the meat or fish in a meal; primaço (a derivation of cousin) is often used in the same situation as "amigo" (friend) is used in other dialects.

Traditional writing system

Siglas Poveiras are a form of 'proto-writing system'; these were used as a rudimentary visual communication system, and are a result of Viking settlers that brought the writing system known as bomärken from Scandinavia about one thousand years ago. The siglas are used as a family "Coat of Arms" or signature to sign belongings.

The siglas were also used to remember things such as marriages, trips, or debts. Thus these were widely used chiefly because many residents did not knew how to use the Latin alphabet, thus these “runes” were widely employed. Merchants used it in their books of credit, and these were read and recognized as we today read and recognize names written in Latin alphabet. These are still used, though much less commonly, by some fishing families.

The inhabitants used to write their sigla in the table of Matriz Church when they got married, as a way to register the event, many ancient siglas can still be found, although many more were lost.

The basic marks were a very restricted number of symbols from which most Siglas derive. These included the arpão, the colhorda, the lanchinha, the pique (including the grade, composed of four crossed piques), and many of these symbols were very similar to those found in Northern Europe, and generally had magical-religious connotations when painted on boats.

Children were given the same family mark with additions, the pique. Thus, the older son would have one pique, the next would have two, and so on. The youngest son would not have any pique, inheriting the same symbol as his father.

Arts and handicrafts

Typical handicrafts include the Tapetes de Beiriz (Beiriz carpets) of the parish of Beiriz. These are distinctive carpets recognized and demanded nationally and internationally. Tapetes de Beiriz decorate the Dutch Royalty Palace and Portuguese public buildings. There are also other handicrafts: the Póvoa’s rendas de bilros, the Mantas de Terroso (Terroso's Blankets) and miniatures of Poveiros boats.

Povoan boats

Main article: Poveiro (boat)The Povoan Boat is a specific genre of boat characterized by a wide flat-bottom and a deep helm. There were diverse boats with different sizes, uses and shapes. Including catraia pequena, catraia grande, caíco and the most notable of which, the Lancha Poveira.

The lancha was a large ship adapted to deep waters and used for hake-fishing. The largest of which had twelve oars and could carry 30 men. Each boat carried carvings, namely a sigla poveira mark for individual boat identification and magical-religious protection at sea. The Lancha Poveira was considered by Lixa Filgueiras and Raul Brandão to be descendant from the Viking longboats, keeping all the longboat features but without a long stern and bow. The ship is completed by a Mediterranean-style sail for better maneuvering.

Literature

Since the 19th century, several relevant writers in the Portuguese language are associated with Póvoa de Varzim. Diana Bar, currently the beach library, was a traditional writers meeting place in early 20th century, and was where José Régio passed his free time writing.[16] Other famous writers closely associated with the city are Almeida Garrett, Camilo Castelo Branco, António Nobre, Agustina Bessa-Luís, D. António da Costa, Ramalho Ortigão, João Penha, Oliveira Martins, Antero de Figueiredo, Raul Brandão, Teixeira de Pascoaes, Alexandre Pinheiro Torres. Nevertheless, the city is often remembered as the birthplace of Eça de Queiroz, one of the main writers in the Portuguese language.

In modern times, the city gained international prominence with Correntes d'Escritas, a literary festival where writers from the Portuguese and Spanish-speaking world gather in a variety of presentations and an annual award for best new release.[17]

Despite its association with several writers, Póvoa as a stage for literary works is rare. Notable exceptions are Luis Sepúlveda's The Worst Stories of the Grim Brothers (in Spanish, Los peores cuentos de los hermanos Grim) and António Nobre who watched Povoan fishermen at sea, sailed with them and wrote poetry about them and their way of living.[18]

Music

Josué Trocado (1882–1962) was a notable composer who organized Orfeon Povoense (Povoan Choral Society), notable all over Portugal for his creativity as a music composer, his choral society was considered by the press as the greatest in Portugal. Trocado wrote plays, namelly Vindima, Cantata, adapted works from other authors, and was the author of Póvoa anthem (Hino da Póvoa de Varzim) in 1916.

The Conjunto Típico Ala-Arriba (1966-1981) was a music group with popular songs based on Povoan themes and wearing Povoan traditional festivity clothing with six commercial records and several presentations in Northern and Southern Portugal. António dos Santos Graça was responsible for the preservation of this traditional clothing and also responsible for the preservation of Povoan fisher folk music and dances by founding the Rancho Folclórico Poveiro in 1936.

Fashion

Traditional clothing

The Camisolas Poveiras are local pullovers made for celebration and decorative purposes, initially used by the fishermen to protect them from the cold. These have fishery motifs and siglas poveiras, drawings related to the Nordic runes. The pullovers have just three colours: white, black and red, with the name embroidered in sigla and more recent examples also carry the name in the Latin alphabet. The pullovers were once a local dress until 1892, when a sea misfortune led the community to stop wearing it. It became popular once again a t the end of the 1970s. Today, there are some efforts to modernize it on one hand and on the other there are endeavours to preserve the long-established practices.

Tricana Poveira

Tricana Poveira were common girls that used foppish costumes. The girls dressed a shawl, an apron, a skirt, a handkerchief and glossy high-heeled slippers. It was said they were the Povoan beauty icons. With their peculiar walking way and dressing style they were girls from the common people with the mannerisms of a queen.[14]

often, tricanas were "land" girls usually employed in sewing jobs, daughters of shoemakers, carpenters and several other crafts. They adapted their knowledge to their own dressing style. Bairro da Matriz quarter was famed for its charming and attractive tricanas. "Fisher" girls, employed in sewing jobs or bobbin lace, were also tricanas.[14]

Fisher women had traditional costumes similar to the tricana girls, but visible poorer, with longer skirt, lower quality materials, darker colors and without the elegance of the typical walking style of the tricana poveira. the pinnacle of the tricana style occurred between the 1920s and the 1960s, creating a strong impact in the communities and amongst outsiders visiting the city.[14]

Tricana costumes were fashion amongst the middle class teenagers until the appearance of ready-to-wear clothing in the 1970s. Nowadays, tricana girls only appear in urban folklore groups, parades, and, only kept as a strong tradition, to this day, during Rusgas de São Pedro (Saint Peter Parades), part of the city festivities in June 28 and 29.[14]

Architecture

Cuisine

The local gastronomy results from the fusing of the Minho and fishing cookery. The most traditional ingredients of the local cuisine are locally-grown vegetables, such as collard greens, cabbage, turnip broccoli, potato, onion, tomato, and a wide variety of fish. The fish used to create the traditional dishes are divided in two categories, the "poor" fish (sardine, ray, mackerel, whiskered sole, and others) and the "wealthy" fish (such as snook, whiting, and alfonsino).

The most famous local dish is Pescada à Poveira (Poveira Whiting), whose main ingredients are, with the fish that gives the name to the dish, potatoes, eggs and a boiled onion and tomato sauce (molho fervido); this dish can be consumed in the ordinary way or, before introducing the sauce, lightly crushing and mixing the ingredients with the fork and knife. This dish also often includes collard greens or turnip broccoli which are not crushed. Other fishery dishes include the Arroz de Sardinha (sardine rice), Caldeirada de Peixe (fish caldeirada), Lulas Recheadas à Poveiro (Poveiro stuffed squids), Arroz de Marisco (seafood rice) and Lagosta Suada (steamed lobster). Mussels, limpets, cockles and periwinkles are cooked in the shell and served as a snack. Iscas, pataniscas and bolinhos de Bacalhau are boiled cod snacks and also popular.

The typical soups are broths (Caldos), one of which is Caldo de Castanhas Piladas (pounded chestnut broth); the nationwide Caldo Verde (green broth) is served on special occasions, such as in Saint Peter's Day.

Other dishes include Feijoada Poveira, made with white beans, chouriça and other meats and served with dry rice (arroz seco); and Francesinha Poveira made in long bread that first appeared in 1962 as fast food for holidaymakers.

Local sweets include barquinhos (cockle-boats), sardinhas (sardines), amor poveiro (or poveirinhos) and beijinhos (little kisses).

Leisure

See also

External links

References

- ^ a b Silva, Luiz Geraldo (2001). A Faina, a Festa e o Rito. Papirus Editora, Campinas, SP. p. 31.

- ^ a b Oliveira, Ernesto Veiga & Galhano, Fernando (1961). Casas de Pescadores da Póvoa do Varzim. Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia v. XVIII. pp. 219–264.

- ^ Carleton Stevens Coon (1939). The Races of Europe. pp. Chapter XI, section 15.

- ^ Fonseca Cardoso (1908). O Poveiro. Portugália, t. II. Porto.

- ^ a b c Baptista de Lima, João (2008). Póvoa de Varzim - Monografia e Materiais para a sua história. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ^ a b c Fangueiro, Óscar (2008). Sete Séculos na Vida dos Poveiros. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ^ Tito... A raça poveira - Varzim S.C.

- ^ a b c d Archivo pittoresco Volume XI. Castro Irmão & C.ª. 1868.

- ^ "Ala-Arriba! (1942)" (in Portuguese). Rascunho. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070211040520/http://www.rascunho.net/critica.asp?id=735. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ "Traje Poveiro - Os Lanchões". Garatujando. http://garatujando.blogs.sapo.pt/arquivo/547533.html. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ http://www.paramiloidose.com/site.php?Tipo=1&IDPag=5160

- ^ "Barco Poveiro" (in Portuguese). Celtiberia. http://www.celtiberia.net/articulo.asp?id=1266. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ^ "Turismo. Conhecer a Póvoa — Siglas Poveiras". CMPV. http://www.cm-pvarzim.pt/turismo/conhecer-a-povoa/siglas-poveiras/. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Azevedo, José de (2007). Poveirinhos pela Graça de Deus. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ^ “Resgatar das Almas” recupera peregrinação a Santo André - CMPV

- ^ ""O Ardina, o Livro Sonhado" apresentado no Diana Bar" (in Portuguese). CMPV. http://www.cm-pvarzim.pt/groups/staff/conteudo/noticias/o-ardina-o-livro-sonhado-apresentado-no-diana-bar. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ "Debate e entrega de prémios encerra 7°Correntes d`Escritas" (in Portuguese). RTP. http://rtp1.rtp.pt/index.php?article=224197&visual=16. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ "O Pescador Poveiro" (in Portuguese). Portal da Póvoa de Varzim. http://www.povoadevarzim.com.pt/pescador.php. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

Póvoa de Varzim topics Main topics History • Culture • Geography • Civil parishes

Landmarks City Hall • Castelo da Póvoa • Monastery of Rates • Matriz Church • Senhora das Dores Church • Coração de Jesus Basilica • Lighthouses (Farol da Lapa & Farol de Regufe) • The Ruins of Cividade de Terroso • Santa Clara Aqueduct • São Félix Hill & Cividade Hill • Alminhas street shrines • Touro • SculpturesNotable streets & squares Praça do Almada (civic center) • Junqueira (shopping street) • Largo David Alves Square • Praça da República • Avenida dos Banhos & Passeio Alegre (waterfront) • Avenida Mousinho de Albuquerque • Avenida Vasco da Gama • Praça Marquês de Pombal • Praça Velha • Largo das Dores Square • Rua Santos MinhoLibraries & museums Diana Bar Beach Library • Rocha Peixoto Municipal Library • Ethnography Museum • A Filantrópica • Santa Casa Museum • Rates EcomuseumEntertainment Casino da Póvoa • Teatro Garrett theatre • Municipal Auditorium (Póvoa de Varzim Orchestra)Beaches & Parks Póvoa_de_Varzim beaches (Enseada da Póvoa bay • Redonda • Salgueira • verde • Beijinhos • Lagoa • Fragosa & Forcado Islet • Esteiro • Coim • Quião • Cape Santo André & Dois Cabos Beach • Santo André • Aguçadoura • Codicheira • Rio Alto) • City Park (Pedreira Lake & Esteiro River) • Rates Park (Serra de Rates) • LotaEthnography Siglas poveiras • Poveiro boat • Ala-Arriba! (film) • Póvoa Hymn • Casa dos PoveirosFamous Food Pescada à poveira • Arroz de marico • Feijoada poveira • Francesinha poveira (fast food) • Rabanada poveira (Dessert)Sports Varzim S.C. • Desportivo da Póvoa • Varzim Stadium • Municipal Stadium • Municipal Pavillion • Póvoa de Varzim BullringCategories:- Portuguese culture

- Fishing communities in Portugal

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.