- Kombucha

-

Kombucha is an effervescent tea-based beverage that is often drunk for its anecdotal health benefits or medicinal purposes. Kombucha is available commercially and can be made at home by fermenting tea using a visible, solid mass of yeast and bacteria which forms the kombucha culture, often referred to as the "mushroom" or the "mother".

Contents

Biology

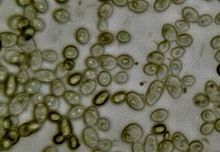

The culture mainly contains a symbiosis of Acetobacter (acetic acid bacteria) and one or more yeasts.

The culture itself looks somewhat like a large pancake, and though often called a mushroom, a mother of vinegar or by the acronym SCOBY (for "Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast"), it is scientifically classified as a zoogleal mat. It takes on the shape of its container, but varies in thickness depending on how long it has been allowed to develop and the acidity of the tea medium during the development period.[citation needed] The culture is leathery and non-elastic, similar to a thick calamari.

The yeast component of kombucha may contain any of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Brettanomyces bruxellensis, Candida stellata, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Torulaspora delbrueckii, and Zygosaccharomyces bailii, or another domesticated strain. Alcohol production by the yeast(s) contributes to the production of acetic acid by the bacteria. Alcohol concentration also plays a role in triggering cellulose production by the bacterial symbionts.[citation needed]

The bacterial component of a kombucha culture usually consists of several species, but will almost always contain Gluconacetobacter xylinus (formerly Acetobacter xylinum), which ferments the alcohols produced by the yeast(s) into acetic acid. This increases the acidity while limiting the alcoholic content of kombucha. G. xylinum is responsible for most or all of the physical structure of a kombucha mother, and has been shown to produce microbial cellulose.[1] This is likely due to artificial selection by brewers over time, selecting for firmer and more robust cultures.

The acidity and mild alcoholic element of kombucha resists contamination by most airborne molds or bacterial spores. As a result, kombucha is relatively easy to maintain as a culture outside of sterile conditions. The bacteria and yeasts in kombucha may also produce antimicrobial defense molecules.

Etymology

Japanese kombu 昆布 "a Laminaria kelp; sea tangle" is dried and powdered to produce a beverage called kombucha (literally "kelp tea"). The English kombucha fermented tea is pronounced similarly, and is confused with the Japanese kombucha seaweed tea.[2]

In Chinese, kombucha is called hongchajun 红茶菌 (lit. "red tea fungus/mushroom"), hongchagu 红茶菇 ("red tea mushroom"), or chameijun 茶霉菌 ("tea mold").

In Japanese, the kombucha drink is known as "kōcha kinoko" 紅茶キノコ (lit. "red tea mushroom"). Both the Chinese and Japanese names incorporate the characters for hongcha or kōcha literally, "red tea," referring to what is known in the West as black tea rather than simply cha 茶 tea or (ryoku cha) 緑茶 "green tea".

History

The recorded history of kombucha began in Russia during the late 19th century.[citation needed] In Russian, the kombucha culture is called čajnyj grib чайный гриб (lit. "tea mushroom"), and the drink itself is called grib гриб ("mushroom"), "tea kvass" чайный квас, or simply kvass, which differs from regular kvass traditionally made from water and stale rye bread.

Some promotional kombucha sources suggest that the history of this tea-based beverage originated in ancient China or Japan, though there are no written records to support these assumptions (see history of tea in China and history of tea in Japan). One author reports that kombucha, famously known as the "Godly Tsche [i.e., tea]" during the Chinese Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), was "a beverage with magical powers enabling people to live forever".[3]

Components

Kombucha contains multiple species of yeast and bacteria along with the organic acids, active enzymes, amino acids, and polyphenols produced by these microbes. The precise quantities of a sample can only be determined by laboratory analysis. Finished kombucha may contain any of the following components:

- Acetic acid, which is mildly antibacterial

- Butyric acid

- B-vitamins[4]

- Alcohol

- Gluconic acid

- Lactic acid

- Malic acid

- Oxalic acid

- Usnic acid

Normally kombucha contains less than 0.5% alcohol, which classifies kombucha as a non-alcoholic beverage.[citation needed] Older, more acidic, kombucha might contain 1.0% or 1.5% alcohol, depending on more anaerobic brewing time and higher proportions of sugar and yeast.[citation needed]

Health claims

Kombucha producers often make the claim that 'kombucha detoxifies the body and energizes the mind', although there is little published research on the health benefits of kombucha. Proponents of kombucha claim it aids cancer recovery, increases energy, sharpens eyesight, aids joint recovery, improves skin elasticity, aids digestion, and improves experience with foods that 'stick' going down such as rice or pasta.

A review of the published literature on the safety of kombucha suggests no specific oral toxicity in rats. [5] While no randomized, case-controlled studies have been published in relation to its effect on humans, its effect on the central nervous system, liver, metabolic acidosis, and toxicity in general, have been suspected in isolated incidents, [6][7] though no specific links have been established. Acute conditions, such as lactic acidosis, caused by drinking of kombucha, are more likely to occur in persons with pre-existing medical conditions. [8] Other reports suggest that care should be taken when taking medical drugs or hormone replacement therapy while regularly drinking kombucha.[9] It may also cause allergic reactions,[10] though a Herxheimer Reaction, or dying off of pathogenic bacteria and yeast, may occur when first beginning consumption of Kombucha, which may be responsible for associated symptoms. [11]

Many claims have focused on glucuronic acid, a compound that is used by the liver for detoxification. The idea that glucuronic acid is present in kombucha is based on the observation that glucuronic acid conjugates (glucuronic acid waste chemicals) are increased in the urine after consumption. Early chemical analysis of kombucha brew suggested that glucuronic acid was the key component, and researchers hypothesized that the extra glucuronic acid would assist the liver by supplying more of the substance during detoxification. These analyses were done using gas chromatography to identify the different chemical constituents, but this method relies on having proper chemical standards[citation needed] to match to the unknown chemicals.

However, a more recent and thorough analysis of a variety of commercial and homebrew versions of kombucha found no evidence of glucuronic acid at all. Instead, the active component is most likely glucaric acid. This compound, also known as D-glucaro-1,4-lactone, helps eliminate glucuronic acid conjugates that are produced by the liver. When these conjugates are excreted, normal gut bacteria can break them up using a bacterial form of beta-glucuronidase. Glucaric acid is an inhibitor of this bacterial enzyme, so the waste stored in the glucuronic acid conjugates is properly eliminated the first time, rather than being reabsorbed and detoxified over and over. Thus, glucaric acid probably makes the liver more efficient.[12]

Glucaric acid is commonly found in fruits and vegetables, and is being explored independently as a cancer preventive agent.[13] It has also been discovered that the bacterial beta-glucuronidase enzyme can interfere with proper disposal of a chemotherapeutic agent, and that antibiotics against gut bacteria can prevent toxicity of some chemotherapy drugs,[14] supporting the idea that glucaric acid is an active component of kombucha.

Reports of adverse reactions may be related to unsanitary fermentation conditions, leaching of compounds from the fermentation vessels,[15] or "sickly" kombucha cultures that cannot acidify the brew. Cleanliness is important during preparation, and in most cases, the acidity of the fermented drink prevents growth of unwanted contaminants.

Other health claims may be due to the simple acidity of the drink, possibly influencing the production of stomach acids or modifying the communities of microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract.[16]

Several firms market Kombucha capsules and tea bags purportedly containing some form of dried Kombucha. There is no supporting evidence that there are any health benefits to such products. Kombucha extract, another suspect product, is also being marketed. Most such extracts are no more than small amounts of Kombucha Tea that has turned vinegary.

Some firms market their Kombucha mushroom cultures based on their size, charging more for larger mushroom cultures. The size of a mushroom culture does not really matter, smaller mushroom cultures will ferment a new batch of prepared tea just as well as a larger mushroom cultures.

Safety and contamination

As with all foods, care must be taken during preparation and storage to prevent contamination. Keeping the kombucha brew safe and contamination-free is a concern to many home brewers. Key components of food safety when brewing kombucha include clean environment, proper temperature, and low pH. If a culture becomes contaminated, it will most likely be identifiable as common mold which is often green, blue, or black in color. Often novice brewers will mistake the brownish root filaments on the underside of the culture as a mold contamination when it is seen through the surface of a thinly formed culture. If mold does grow on the surface of the kombucha culture, or "mushroom," it is best to throw out both culture and tea and start again with a fresh kombucha culture.

Mold tends to grow especially when the kombucha mushroom is lifted out of the liquid by its own gasses. Keeping it covered with liquid in the later stages, i.e. when the new kombucha mushroom starts growing, can successfully prevent mold from growing.

The low rate of contamination by the home brewer might be explained by protective mechanisms, such as formation of organic acids and antibiotic substances. Thus, subjects with a healthy metabolism need not be advised against cultivating kombucha tea cultures. However, those suffering from immunosuppression should preferably consume controlled commercial kombucha beverages.[17]

In every step of the preparation process, it is important that hands and utensils (or anything that is going to come into contact with the culture) be well cleaned to prevent contamination of the kombucha. Also, kombucha becomes very acidic (approximately pH 3.0 when finished), so it can leach unwanted and potentially toxic materials from the non food grade containers in which it is fermenting.[15] Food-grade glass is very safe. Other acceptable containers may also include lead free china, raw wooden bowls, glazed earthenware (lead free - there are kits that can test ceramics), and stainless steel.[18] Keeping cultures covered and in a clean environment also reduces the risk of introducing contaminants and insects.

Maintaining a correct pH is an important factor in a home-brew. Acidic conditions are favorable for the growth of the kombucha culture, and inhibit the growth of molds and bacteria. The pH of the kombucha batch should be between 2.5 and 4.6. A pH of less than 2.5 makes the drink too acidic for normal human consumption, while a pH greater than 4.6 increases the risk of contamination.[19] Use of fresh "starter tea" and/or distilled vinegar can be used to control pH. Some brewers test the pH at the beginning and the end of the brewing cycle to ensure that the correct pH is achieved and that the brewing cycle is complete.

Brew

Kombucha is typically produced by placing a culture in a sweetened tea, as sugars assist fermentation. Black tea is a popular choice but green tea or white tea may also be used. Blending of tea may produce more balanced flavors and benefits from the different types of teas. Herbal teas or those treated with oils may harm the Kombucha culture over time. [20]

The standard Kombucha recipe calls for 1 cup of sugar per gallon of water/tea, though some variation in the ratio is tolerated by the culture. Kombucha may be fermented with many different sugar sources including refined white sugar, evaporated cane juice, brown sugar, glucose/fructose syrups, molasses and honey (pasteurized only). Kombucha should never be fermented with raw honey, stevia, xylitol, lactose, or any artificial sweetener. [21]

The container is often covered with a closed weave cloth to prevent contamination by dust, mold, and other bacteria, while allowing gas transfer ("breathing"). A "baby" SCOBY is produced on the liquid/gas interface during each fermentation. The surface area is the most favorable location for both aerobic bacteria on the top of the new "pancake" and anaerobic bacteria on the bottom. The surface area also has ideal concentration of oxygen for the yeast in the matrix to propagate readily.

After a week or two of fermentation, the liquid is tapped. Some liquid is retained for the subsequent batch to keep the pH low to prevent contamination. This process can be repeated indefinitely. In each batch, the "mother" culture will produce a "baby", which can be directly handled, separated like two pancakes, and moved to another container. The yeast in the tapped liquid will continue to survive. A secondary fermentation may be accomplished by removing the liquid to a closed container (bottle) for about a week to produce more carbonation. Care should be taken as carbon dioxide build up can cause bottles to explode.

Left entirely alone to ferment with oxygen, the kombucha settles into months of production time (the "baby" thickening considerably), creating an ever more acidic and vinegar-flavored cider. At any point the kombucha can be tapped or have tea added. Liquid from the previous batch will preserve some of the culture.

Some tea makers offer a dried version of kombucha, mixed with the tea leaves, that dissolves in hot water; however, this is a more rare type.

Artificial leather

The Kombucha SCOBY can be used to make an artificial leather, though currently it is very water absorbent.[22]

See also

References

- ^ A paper describing the isolation of Gluconacetobacter xylinus from kombucha

- ^ Crystal Wong, U.S. 'kombucha': smelly and no kelp, The Japan Times July 12, 2007

- ^ Harald W. Tietze, 1995, Kombucha" The Miracle Fungus, Tietze Publications,

- ^ Aleksandra, Velicanski; Dragoljub, Cvetkovic; Sinisa, Markov; Vesna, Tumbas; Sladjana, Savatovic (2007). "Antimicrobial And Antioxidant Activity Of Lemon Balm Kombucha". Acta periodica technologica (38): 165. doi:10.2298/APT0738165V. http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/(A(LEQaRwCVyAEkAAAANWQzYjNhNjMtYjc2Mi00NDkzLTkxM2QtYWE0MTlhYTYyOGQxWFjX2eJbVjiuapiC3RRpn5ACeII1))/ft.aspx?id=1450-71880738165V.

- ^ Subacute(90Days) Oral Toxicity Studies of Kombucha Tea 生物医学与环境科学:英文版-作者:R.VIJAYARAGHAVAN MANINDERSINGH 等

- ^ Ernst E (April 2003). "Kombucha: a systematic review of the clinical evidence". Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd 10 (2): 85–7. doi:10.1159/000071667. PMID 12808367. http://content.karger.com/produktedb/produkte.asp?typ=fulltext&file=FKM2003010002085.

- ^ SungHee Kole A, Jones HD, Christensen R, Gladstein J (2009). "A case of Kombucha tea toxicity". J Intensive Care Med 24 (3): 205–7. doi:10.1177/0885066609332963. PMID 19460826. http://jic.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19460826.

- ^ Kole, Alison SungHee; Jones (2009). "Heather D". Journal of Intensive Care Medice (Sage Publications Inc.) 24 (3): 205–207.

- ^ Srinivasan MD, Radhika; Susan Smolinske, PharmD & David Greenbaum MD (October 1997). "Probable Gastrointestinal Toxicity of Kombucha Tea Is This Beverage Healthy or Harmful?". Journal of General Internal Medicine 12 (10): 643–5. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07127.x. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/links/doi/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07127.x.

- ^ Kombucha "Mushroom" Hepatotoxicity

- ^ Kombucha & The Healing Crisis: Herxheimer Reactions

- ^ Michael R. Roussin (1996-2003). Analyses of Kombucha Ferments. Information Resources, url=http://www.kombucha-research.com.

- ^ Walaszek, Z. (1990-10-08). "Potential use of D-glucaric acid derivatives in cancer prevention". Cancer Letters (Elsevier Science Ireland) 54 (1–2): 1–8. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(90)90083-A. PMID 2208084.

- ^ Involvement of ß-Glucuronidase in Intestinal Microflora in the Intestinal Toxicity of the Antitumor Camptothecin Derivative Irinotecan Hydrochloride (CPT-11) in Rats

- ^ a b Phan, Tri Giang; Jane Estell, Geoffrey Duggin, Ian Beer, Diane Smith and Mark J Ferson (1998). "Lead poisoning from drinking Kombucha tea brewed in a ceramic pot". The Medical Journal of Australia (Australasian Medical Publishing Company) 169 (11-12): 644–646. PMID 9887919. http://mja.com.au/public/issues/xmas98/phan/phan.html.

- ^ Harald W. Tietze, Living Food for Longer Life

- ^ MAYSER P. (1) ; FROMME S. ; LEITZMANN C. ; GRÜNDER K. (1998). "The yeast spectrum of Kombucha". Blackwell, Berlin, ALLEMAGNE. http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=2897443.

- ^ How to make your own Kombucha Tea

- ^ Nirinjan Singh (2005). "Ph Levels For Kombucha Tea Beverage". http://www.organic-kombucha.com/kombucha_and_ph.html.

- ^ Teas To Use & Teas To Avoid When Making Kombucha

- ^ Top 10 Questions About Kombucha & Sugar

- ^ Video of a short talk by a clothes designer about making and using a material made of kombucha

Bibliography

- Harald W. Tietze (1995). Kombucha: The Miracle Fungus. London: Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 1-85860-029-4.

- Dipti P, Yogesh B, Kain AK, et al. (September 2003). "Lead induced oxidative stress: beneficial effects of Kombucha tea". Biomed. Environ. Sci. 16 (3): 276–82. PMID 14631833.

- Ernst, E. (2003). "Kombucha: a systematic review of the clinical evidence". Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd / Research in Complementary and Classical Natural Medicine 10 (2): 85–7. doi:10.1159/000071667. PMID 12808367. http://content.karger.com/produktedb/produkte.asp?typ=fulltext&file=FKM2003010002085.

- Pauline T, Dipti P, Anju B, et al. (September 2001). "Studies on toxicity, anti-stress and hepato-protective properties of Kombucha tea". Biomed. Environ. Sci. 14 (3): 207–13. PMID 11723720.

- Teoh AL, Heard G, Cox J (September 2004). "Yeast ecology of Kombucha fermentation". Int. J. Food Microbiol. 95 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020. PMID 15282124. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168160504001072.

- Günther W. Frank (1995). Kombucha: Healthy Beverage and Natural Remedy from the Far East, Its Correct Preparation and Use. Wilhelm Ensthaler. ISBN 3-85068-337-0.

External links

Categories:- Fermented beverages

- Fermented foods

- Carbonated drinks

- Tea

- Chinese tea

- Mycology

- Toxicology

- Synthetic materials

- Nonwoven fabrics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.