- Ralph Adams Cram

-

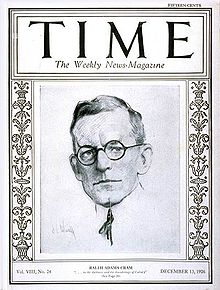

Ralph Adams Cram

Ralph Adams Cram, 1911Born December 16, 1863

Hampton Falls, New HampshireDied September 22, 1942 Nationality USA Known for Architect Ralph Adams Cram FAIA, (December 16, 1863 - September 22, 1942), was a prolific and influential American architect of collegiate and ecclesiastical buildings, often in the Gothic style. Cram & Ferguson and Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson are partnerships in which he worked.

Contents

Early life

Cram was born on December 16, 1863 at Hampton Falls, New Hampshire to the Rev. William Augustine and Sarah Elizabeth Cram. He was educated at Augusta, Hampton Falls, Westford Academy and Exeter.[1] While his father was a Unitarian minister, he called himself an agnostic in his youth.[citation needed]

Cram moved to Boston in 1881, at age 18, and spent five years in the architectural office of Rotch & Tilden,[2] after which he left for Rome. During an 1887 Christmas Eve mass in Rome, he had a dramatic conversion experience.[3] For the rest of his life, he remained a fervent Anglo-Catholic who self-identified as High Church Anglican.

In 1900 Cram married Elizabeth Carrington Read at New Bedford. She was the daughter of Captain Clement Carrington Read C.S.A. and bore him two children, Mary Carrington and Ralph Wentworth.[1]

Career

Cram and business partner Charles Wentworth started business in Boston in April 1889 as Cram and Wentworth. They'd landed only four or five church commissions before they were joined by Bertram Goodhue in 1892 to form Cram, Wentworth and Goodhue. Goodhue brought an award-winning commission in Dallas (never built) and brilliant drafting skills to the Boston office.

Wentworth died in 1897 and the firm's name changed to Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson to include draftsman Frank Ferguson. Cram and Goodhue complemented each others' strengths at first but shifted into competition, sometimes submitting two differing proposals for the same commission. The firm's win of the 'United States Military Academy at West Point' project in 1902 was a major milestone in their career, and it meant the establishment of the firm's New York office, where Goodhue would preside, leaving Cram to operate in Boston.

Cram's acceptance of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine commission in 1911 (on Goodhue's perceived territory) heightened the tension between the two. Close attention can attribute most projects to one partner or the other, based on the visual and compositional style and the location. The Gothic Revival Saint Thomas Church was designed by them both in 1914 on Manhattan's Fifth Avenue in New York City. It is the last example of their collaboration, and the most integrated and strongest example of their work together.

Goodhue began his solo career on August 14, 1913. Cram and Ferguson continued with major church and college commissions through the 1930s. The successor firm is HDB/Cram and Ferguson of Boston.

A leading proponent of disciplined Gothic Revival architecture in general and Collegiate Gothic in particular, Cram is most closely associated with Princeton University, where he was awarded a Doctor of Letters[1] and served as Supervising Architect from 1907 to 1929. For seven years he headed the Architectural Department at Massachusetts Institute of Technology,[4]

Through the 1920s Cram was a public figure and frequently mentioned in the press. The New York Times called him "one of the most prominent Episcopalian laymen in the country". He made news with his defense of Al Smith, saying "I... express my disgust at the ignorance and superstition now rampant and in order that I may go on record as another of those who, though not Roman Catholics, are nevertheless Americans and are outraged by this recrudescence of blatant bigotry, operating through the most cowardly and contemptible methods."[5]

Cram and Modernism

As an author, lecturer, and architect, Cram propounded the view that the Renaissance had been, at least in part, an unfortunate detour for western culture.[6] Cram argued that authentic development could come only by returning to Gothic sources for inspiration,[7] as his "Collegiate Gothic" architecture did, with considerable success. He was not altogether inflexible on this point, however, rejecting Gothic for his Rice University buildings in favor of a medieval north Italian Romanesque style more in keeping with Houston's hot, humid climate. A modernist in many ways, to the chagrin of many traditionalists today, he designed Art Deco landmarks of great distinction, including the Federal Building skyscraper in Boston and a great number of churches in deco style. For example, his design of the tower of the East Liberty Church, Pittsburgh, was inspired by the Empire State Building. His work at Rice was as modernist as medieval in inspiration. His administration building there, his secular masterwork, has been compared by Shand-Tucci to Frank Lloyd Wright's work, particularly in the way its dramatic horizontality reflects the surrounding prairies.

In his review of the standard biography of Cram by Douglass Shand-Tucci, Yale professor and architectural historian Sandy Isenstadt writes: "what Shand-Tucci has done in this book...is to demonstrate how much (modernist) disdain (of Cram) turned out to be modernism's loss". Similarly, in another review by Peter Cormack, director of London's William Morris Gallery, the British scholar commented on the neglect of Cram's work, "a phenomenon which has significantly distorted the study of America's modern architectural history... (Cram) deserves the same kind of international--and domestic--recognition accorded (all too often uncritically) to his contemporary Frank Lloyd Wright".

Veneration

Cram is honored together with Richard Upjohn and John LaFarge with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on December 16.

Works

Buildings

Cram's buildings include:

- The Birches, Garrison, New York, 1882

- Rehoboth, Chappaqua, New York, 1891-1892

- All Saints' Church, Ashmont, Massachusetts, 1892

- Christ Church (Hyde Park, Massachusetts), 1892

- Church of St. John Evangelist, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1892

- Lady Chapel, Church of the Advent, Boston, Massachusetts, 1894

- Richmond Court, Brookline, Massachusetts, 1896

- Philips Church, Exeter, New Hampshire, 1897

- Public Library, Fall River, Massachusetts 1899

- Deborah Cook Sayles Public Library, Pawtucket, Rhode Island, 1899

- Emmanuel Church, Newport, Rhode Island, 1900

- Calvary Episcopal Church, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1904

- Holy Cross Monastery, West Park, New York, with Henry Vaughan, 1904

- All Saints' Chapel, Sewanee: The University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee, begun 1904, finished 1959

- The Mather School, Dorchester, Massachusetts, 1905

- La Santisima Trinidad pro-cathedral, Havana, Cuba, 1905

- Saint Thomas Church, New York City, 1905–1913

- First Unitarian Society in Newton, Massachusetts, 1905–1906

- Many buildings at Sweet Briar College, including Mary K. Benedict Hall, Fletcher Hall, Mary Harley Student Health and Counseling Center, Mary Helen Cochran Library. Sweet Briar, Virginia, 1906–1928

- Cathedral Church of St. Paul, Detroit, Michigan, 1908

- Russell Sage Memorial Church, Far Rockaway, New York, 1908-1910[8]

- St. Florian Church, Hamtramck, Michigan, 1910, expanded by Cram 1928

- master plan and multiple buildings at Rice University, Houston, Texas, 1910–1916

- Ryland Hall, Jeter Hall and North Court, all at Richmond College, Richmond, Virginia, 1910

- All Saints Cathedral, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1910

- Park Avenue Christian Church, NYC, 1911

- Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York City, begun 1912, unfinished

- remodeling of Richard Upjohn's Grace Church, Providence, Rhode Island, 1912

- multiple buildings at Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, including the 1927 Cleveland Tower, the 1928 Princeton University Chapel, Campbell Hall, McCormick Hall, and multiple buildings of the Graduate College, 1913–1927

- Saint Paul's Episcopal Parish, Malden, Massachusetts, begun 1913, unfinished

- Fourth Presbyterian Church, Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 1914

- multiple buildings at the Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, New Hampshire, including the 1914 Academy Building

- Chapel of St. Anne, Arlington, Massachusetts, 1915

- All Saints Church (Peterborough, New Hampshire), ca 1916-1920

- Chapel of Mercersburg Academy, Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, 1916–1928

- Cole Memorial Chapel, Wheaton College, Norton, Massachusetts, 1917

- Trinity Episcopal Church, Houston, Texas, 1919

- St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral, Hastings, Nebraska, 1921–1929

- Second Presbyterian Church (Lexington, Kentucky), 1922

- Sacred Heart Church, Jersey City, New Jersey, 1923

- buildings at The Choate School, Wallingford, Connecticut, 1924–1928, including St. Andrews Chapel (now Seymour St. John Chapel) and Archbold Infirmary (now Archbold House)

- First Presbyterian Church, Utica, New York, 1924

- First Presbyterian Church, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1925–27

- Julia Ideson Building of the Houston Public Library, Houston, Texas, 1926

- Chapel at St. George's School, Newport, Rhode Island, 1928

- Holy Rosary Roman Catholic Church, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1928

- First Presbyterian Church of Glens Falls, Glens Falls, New York, 1928

- St. Paul's Episcopal Church, Winston-Salem, NC Winston-Salem, 1928

- Concordia Lutheran Church, Louisville, Kentucky, 1930

- Knowles Memorial Chapel, on the campus of Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida, 1931–1932

- chancel, Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church, Baltimore, Maryland, 1931

- Doheny Library, Campus of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 1931

- Saint Mary's Academy, Glens Falls, New York, 1932

- Cathedral of Hope, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1932–1935

- U.S. Post Office and Courthouse aka J.W. McCormack Post Office and Courthouse, Boston, Massachusetts, 1933

- Conventual Church of St. Mary and St. John, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1936

- buildings at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery and Memorial, Belleau, France, 1937

- buildings at the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery and Memorial, Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne department, France, circa 1937

- Berkeley Building, Boston, Massachusetts, 1947

- St. James' Church, New York, renovation, 1924

Publications

Cram authored numerous publications and books on issues in architecture and religious devotion. Titles include:

- Impressions of Japanese Architecture, The Baker & Taylor Company, 1905

- Heart of Europe, MacMillan & Co. London, 1916 325pgs.

- The Substance of Gothic, Marshall Jones Company, Boston, 1917

- Sins Of The Fathers, Marshall Jones Company, Boston, 1918

- Walled Towns, Marshall Jones Company, Boston, 1919

- Towards the Great Peace, Marshall Jones Company, Boston, 1922

Cram was also a writer of fiction. A number of his stories, notably "The Dead Valley", were published in a collection entitled Black Spirits and White (Stone & Kimball, 1895). The collection has been called "one of the undeniable classics of weird fiction".[9] H. P. Lovecraft wrote, "In The Dead Valley the eminent architect and mediævalist Ralph Adams Cram achieves a memorably potent degree of vague regional horror through subtleties of atmosphere and description."[10]

Professional memberships etc

Cram[1] was a

- Fellow of the:

- Boston Society of Architects.

- American Institute of Architects.

- North British Academy of Arts.

- Royal Geographical Society of London.

- Member of the:

- American Federation of Arts.

- Architectural Association of London.

- Member of the clubs

- Puritan Club (Boston).

- Century Club (New York).

See also

- List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s - 13 Dec. 1926

References

- ^ a b c d New Architect of St. John's Cathedral in Oswego Daily Times, September 22, 1911, Page 7d

- ^ Shand-Tucci, Douglass (2000) (revised and expanded ed.). Built in Boston: City and Suburb, 1800-2000, p. 163. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-201-1.

- ^ Shand-Tucci, Douglass Boston Bohemia, p.68-70

- ^ "Ralph Cram Dies; Noted Architect; Redesigner of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine Here Stricken in Boston; An Authority on Gothic; Fashioned Buildings for West Point and Princeton; Wrote on Religion," The New York Times, September 23, 1942, p. 25

- ^ "Cram backs Smith as Bigotry Protest", The New York Times, September 14, 1928, p. 4

- ^ Cram, Ralph Adams (1914). The Ministry of Art. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ Shand-Tucci (2000), p. 162.

- ^ Merrill Hesch (July, 1986). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Russell Sage Memorial Church / First Presbyterian Church of Far Rockaway". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. http://www.oprhp.state.ny.us/hpimaging/hp_view.asp?GroupView=7399. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- ^ Ashley, Mike (2004). The Mammoth Book of Sorcerer's Tales, p. 284. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1408-5.

- ^ Supernatural Horror in Literature, text online at online text

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass. Ralph Adams Cram: Life and Architecture. 2 volumes. Boston Bohemia (University of Massachusetts Press, 1994) ISBN 1-55849-061-2, ISBN 978-1-55849-061-1; Ralph Adams Cram: An Architect's Four Quests (University of Massachusetts Press, 2005). ISBN 978-1-55849-489-3 ISBN 1-55849-489-8.

External links

- Works by Ralph Adams Cram at Project Gutenberg

- Cram and Ferguson Architects

- audio tour (part 2) that covers Cram

- review of recent Cram book

- Recent book on Cram by Ethan Anthony

- Cram and Ferguson Architects Website

- Why We Do Not Behave Like Human Beings, essay by Cram

- Boston Public Library. Cram, Ralph Adams (1863-1942) Collection

- Ralph Adams Cram at Find a Grave

Categories:- 1863 births

- 1942 deaths

- People from Hampton Falls, New Hampshire

- American Episcopalians

- American architects

- Gothic Revival architects

- American ecclesiastical architects

- University of Notre Dame people

- Architecture of Phillips Exeter Academy

- Anglo-Catholics

- American saints

- Anglican saints

- Ralph Adams Cram buildings

- Architects of Roman Catholic churches

- Architects of cathedrals

- Architects from Massachusetts

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.