- Leslie Morshead

-

Sir Leslie James Morshead

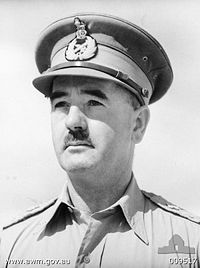

Leslie Morshead in 1941Nickname 'Ming the Merciless' Born 18 September 1889

Ballarat, VictoriaDied 26 September 1959 (aged 70)

Sydney, New South WalesAllegiance Australia Service/branch Australian Army Years of service 1913–1946 Rank Lieutenant General Service number NX8 Commands held 33rd Infantry Battalion

18th Infantry Brigade

9th Division

II Corps

New Guinea Force

Second Army

I CorpsBattles/wars Awards Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

Distinguished Service Order

Efficiency Decoration

Mention in Despatches (8)

Légion d'honneur (France)

Virtuti Militari (Poland)

Medal of Freedom (United States)Other work Teacher, farmer, manager of the Orient Steam Navigation Company Lieutenant General Sir Leslie James Morshead KCB, KBE, CMG, DSO, ED (18 September 1889 – 26 September 1959) was an Australian soldier, teacher, businessman, and farmer, with a distinguished military career that spanned both world wars. Most notably, during World War II he commanded the Australian and British troops at the Siege of Tobruk and at the Second Battle of El Alamein, achieving decisive victories over the German Afrika Korps, led by Erwin Rommel. Morshead went on to lead the Australian forces against the Empire of Japan during the New Guinea and Borneo campaigns. A strict and demanding officer, he came to be referred to by his soldiers humorously as "Ming the Merciless," and later simply as "Ming," after the villain in Flash Gordon comics.[1] Morshead has been described as "arguably Australia's greatest soldier after Blamey."[2]

Contents

Early life

Morshead was born on 18 September 1889 in Ballarat, Victoria, the sixth of seven children of William Morshead, a gold miner who had emigrated from Cornwall, and his wife Mary Eliza Morshead, formerly Rennison, a native of South Australia.[1] He was educated at Mount Pleasant High School and the Melbourne Teachers Training College, from which he graduated in 1910.[3]

He became a schoolteacher, teaching first at Tragowell in the Swan Hill district, at Fine View State School, and then in the Horsham district. After failing an exam at the University of Melbourne, he decided to quit the state school system and in 1912 took up a position at The Armidale School in New South Wales. In 1914 he moved to Melbourne Grammar School.[4]

While at Armidale, Morshead joined the Australian Army Cadets, and was commissioned as a lieutenant on 10 February 1913. He was promoted to captain in September. At Melbourne he commanded a company in that schools' larger cadet unit.[5]

World War I

Morshead's teaching career was interrupted by the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. He resigned both his teaching position and his commission in the Cadet Corps and travelled up to Sydney to enlist as a private in the 2nd Infantry Battalion of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) because it was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Braund, whom Morshead knew well from his time in Armidale. Morshead's time in the ranks was brief, as he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the AIF on 19 September. He embarked for Egypt on the transport A23 Suffolk on 18 October 1914. While his battalion was in training there, he was promoted to captain on 8 January 1915.[6]

The 2nd Battalion landed at Anzac Cove on Anzac Day. Morshead's platoon made the farthest advance of an Australian unit that day, reaching the slopes of Baby 700 but were driven back by a Turkish counter-attack in the afternoon.[7] Promoted to major, Morshead served with his 2nd Battalion in the Battle of Gallipoli, distinguishing himself in the Battle of Lone Pine.[8] On 16 September, like so many others, he succumbed to dysentery and was evacuated to a hospital in Wandsworth, England.

Morshead returned to Australia on 22 January 1916 where he was posted to the newly-formed 33rd Infantry Battalion. On 16 April he became its commander and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel three days later.[9] He led his battalion, part of Major General John Monash's 3rd Division through the battles of Messines, Passchendaele, Villers-Bretonneux and Amiens. For his services, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in June 1917,[10] made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in December 1919,[11] was awarded the French Légion d'honneur in the grade of Chevalier,[12] and was Mentioned in Despatches five times.

Between the wars

Morshead returned to Australia in November 1919 and his AIF appointment was terminated in March 1920. He tried farming — accepting a soldier settlement block of 23,000 acres (9,300 ha) near Quilpie, Queensland. This venture was a failure. After working odd jobs he joined the Orient Line in Sydney on 24 October 1924. He was appointed passenger manager of the Sydney office in 1926. Many Orient Line appointments followed including: publicity manager in January 1927; acting manager of the Melbourne office in May 1928; passenger and publicity superintendent; temporary business manager Brisbane in April 1931; of the Melbourne office, which became permanent in December 1933; and the Sydney office in 1937.[13]

He married Myrtle Catherine Hay Woodside, whom he had known since his days at Melbourne Grammar when she was a schoolgirl, at Scots Church, Melbourne, on 17 November 1921. They had a daughter, Elizabeth.[1]

Throughout the inter-war years he remained active in the part-time CMF, commanding the 19th and 36th Infantry Battalions in turn. Promoted to colonel in 1933 and brigadier in 1938, he was appointed to command the 14th Infantry Brigade in 1933. When he moved to Melbourne in 1934, he transferred to command of the 15th Infantry Brigade, then part of the 3rd Division under Major General Sir Thomas Blamey. On returning to Sydney in 1937, commanded the 5th Infantry Brigade.

Known for his right-wing views even before the war, he was also a member of the clandestine far-right wing paramilitary organisation known as the New Guard.[14]

World War II

On 6 October 1939, Morshead was selected by Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Blamey to command the 18th Infantry Brigade in the new 6th Division. This brigade was composed of four battalions from the smaller states, and would have been a natural assignment for a regular officer had Prime Minister Robert Menzies not restricted appoints to senior posts to Militia officers, few of whom had much experience of the Army outside their home states. Morshead met with Blamey on 13 October to select officers for the new brigade.[15] He was given a regular officer as Brigade Major, Major Ragnar Garrett.

Morshead formally enlisted in the Second AIF on 10 October 1939 and was given the AIF serial number NX8. He was given the rank of colonel and temporary brigadier three days later. A delay in preparing its camp at great in the Hunter Valley meant that it was not concentrated there until December. In the meantime its battalions trained in their home states. After the 16th Infantry Brigade departed for Palestine in January 1940, the 18th Infantry Brigade moved into its vacated accommodation at Ingleburn, New South Wales. As a consequence, its training proceeded more slowly than that of the 16th and 17th Infantry Brigades.[16]

The 18th Infantry Brigade finally embarked from Sydney on the Mauretania on 5 May 1940 but en route was diverted to the United Kingdom owing to the dangerous military situation there following the Battle of France. It moved into camps on the Salisbury Plain, where the 3rd Division had trained back in 1916. The Australian force there under Major General Henry Wynter was poorly equipped but the 18th Infantry Brigade was nonetheless given an important role in the defence of Southern England. In September 1940, Wynter was informed that his force would become the nucleus of a new 9th Division, which he was appointed to command. Morshead and his 18th Infantry Brigade embarked for the Middle East on 15 November, reaching Alexandria on 31 December.[17] Morshead was made a Commander of Order of the British Empire on 1 January 1941.[18]

Before his other two brigades could arrive from England and Australia, Wynter became seriously ill. Blamey decided to send him home and appointed Morshead to command the 9th Division on 29 January 1941.[19]

According to Official Historian Barton Maughan:

“ Morshead was every inch a general. His slight build and seemingly mild facial expression masked a strong personality, the impact of which, even on a slight acquaintance, was quickly felt. The precise, incisive speech and flint-like, piercing scrutiny acutely conveyed impressions of authority, resoluteness and ruthlessness. If battles, as Montgomery was later to declare, were contests of wills, Morshead was not likely to be found wanting.[20] ” Tobruk

In February 1941, the 9th Division was completely reorganised, with its 18th and 25th Infantry Brigades transferred to the 7th Division. In return, it received the 20th and 24th Infantry Brigades, the latter short one battalion which was on garrison duty in Darwin. The 9th Division, less it partly trained and equipped artillery, was ordered to move to the Tobruk-Derna area where it would relieve the 6th Division, so that formation could participate in the Battle of Greece.[21]

The half-trained and half-equipped 9th Division was pitched into the thick of the action almost immediately, steadying the retreat of Commonwealth forces from the newly-arrived German Afrika Korps, under Erwin Rommel, and occupying the vital port of Tobruk in Libya. Morshead was given command of the Tobruk garrison which, as the retreat (known to the Australians as the "Benghazi handicap") continued, became surrounded, hundreds of miles behind enemy lines. Lieutenant General John Lavarack determined that Tobruk could be held and ordered Morshead to defend it. He also ordered the 18th Infantry Brigade to reinforce the garrison, bringing it to four brigades, and British artillery and tank units up to provide support.[22]

General Archibald Wavell instructed Morshead to hold the fortress for eight weeks, while the remaining forces reorganised and mounted a relief mission. With the 9th Division, 18th Infantry Brigade and supporting forces from various Allied nations, Morshead's force decisively defeated Rommel's powerful initial assaults, and retained possession of the fortress. His strategy for the defence of Tobruk is still mentioned in officer training colleges around the world as an example of how to arrange and conduct in-depth defences against a superior armoured force.

An important part of Morshead's strategy was offensive operations when these were possible. His attitude was summed-up in a reported remark, made when his attention was drawn to a British propaganda article entitled "Tobruk can take it!" Morshead commented: "we're not here to take it, we're here to give it.". The 9th Division held Tobruk not for eight weeks, but for eight months, during which time three separate relief campaigns, by the main Allied force in Egypt failed. The Axis troops learned to fear the aggressive patrolling of the Australian infantry who dominated no-man's-land and made constant raids on enemy forward positions for intelligence, to take prisoners, to disrupt attack preparations and minelaying operations, even to steal supplies that were not available in Tobruk. Axis propagandists described him as "Ali Baba Morshead and his 40,000 thieves" and branded the defenders of the port as the "Rats of Tobruk", a sobriquet that they seized on and wore as a badge of pride.

By July 1941, Morshead had become convinced that his troops were becoming tired. Their health was deteriorating and, in spite of his efforts, their morale and discipline were slipping. He informed Generals Blamey and Auchinleck that they should be relieved.[23] Auchinleck arranged for the 18th Infantry Brigade to be relieved by the Polish Carpathian Brigade so that it could rejoin the 7th Division in August but baulked at relieving the 9th Division.[24]

At this point, political considerations came into play. The newly installed government of Prime Minister John Curtin in Australia, on Blamey's advice, took up the matter with Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who protested that the relief would cause a postponement of Operation Crusader. As it turned out, the operation had to be postponed anyway. In October 1941, Morshead and most of the 9th Division was replaced by the British 6th Division. The 9th Division moved to Syria to serve as an occupation force, as well as resting, re-equipping and training reinforcements.[25]

The Battle of Tobruk marked the first time that the Panzerwaffe had been defeated in battle. For his part, Morshead was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) on 6 January 1942.[26] He was also awarded the Virtuti Militari by the Polish government in Exile and was decorated by Generał broni Władysław Sikorski on 21 November 1941.[27]

El Alamein

Morshead (centre) with Winston Churchill (left) and General Claude Auchinleck (right) in August 1942

Morshead (centre) with Winston Churchill (left) and General Claude Auchinleck (right) in August 1942

The outbreak of war with Japan, in December 1941, and the imminent threat of invasion saw Blamey and the 6th and the main bodies of the 7th Division transferred to Ceylon and Australia respectively, in early 1942. In March that year, Morshead was given command of all Australian forces in the Mediterranean theatre and was promoted to lieutenant general.

Morshead was one of only a few Allied divisional commanders with a distinct record of success at this stage of the war and had been acting commander of the British XXX Corps, a formation largely composed of Commonwealth troops, on two occasions. He had hopes that he might be given command of the corps, as Harry Chauvel had been in the Great War. But while Chauvel had been an Australian, he had been a regular officer while Morshead was not and the new commander of the British Eighth Army, Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery felt that a reservist could not possess the "requisite training and experience" to command a corps and Morshead was passed over in favour of Oliver Leese, a British regular officer, who was junior to him and had never commanded a division in action.[28]

At the Second Battle of El Alamein, the 9th Division was given responsibility for clearing a corridor through the German and Italian forces in the North and threatening to cut off those between the coastal road and the sea. In the initial assault the division hacked its way through the enemy defences but failed to clear the minefields. However, as the British attack faltered, the main effort switched to the 9th Division, which punched a massive dent into the German and Italian position over the next five days at great cost, "crumbling" the Afrika Korps in the process, and ultimately forcing Rommel to retreat. "I am quite certain," Leese informed Morshead, that this breakout was made possible by Homeric fighting over your divisional sector." During the El Alamein Campaign, the 9th Division suffered 22% of the British Eighth Army's casualties; 1,177 Australians were killed, while 3,629 were wounded, 795 were captured and 193 were missing.[29]

For his part in the famous victory, Morshead received yet another Mention in Despatches in June 1942[30] and in November 1942 he was also created a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB).[31]

New Guinea Campaign

After El Alamein, Morshead and the 9th Division were recalled to the South West Pacific Area. Morshead arrived in Fremantle on 19 February 1943 where he was welcomed home by Lieutenant General Gordon Bennett, who had been his division commander between the wars. Morshead then flew to Melbourne where he was met by Lady Morshead, Sir Winston Dugan and Sir Thomas Blamey, who informed Morshead that he would take over command of a corps. In March 1943, Morshead became commander of the II Corps, handing over command of the 9th Division to Major General George Wootten. The association between Morshead and the 9th Division was not entirely broken however, as it formed part of his corps, along with the 6th and 7th Divisions. All three were undergoing jungle training on the Atherton Tableland for upcoming battles in New Guinea.[32]

It was Blamey's intention that Morshead would spend some time learning the art of jungle warfare before his II Corps replaced Lieutenant General Sir Edmund Herring’s I Corps in New Guinea.[33] In late September 1943, Morshead was summoned to New Guinea to relieve Herring by Lieutenant General Sir Iven Mackay, the commander of New Guinea Force, which he did on 7 October 1943.

Morshead found a difficult situation. The Japanese not only held the high ground overlooking the Australian beachhead at Finschhafen, they were rapidly reinforcing their position and were about to mount a major counterattack. Morshead demanded and got critical reinforcements, including Matilda tanks of the 1st Tank Battalion. The Japanese counterattack was crushed.[34]

Afterward, Morshead relieved Brigadier Bernard Evans of command of the 24th Infantry Brigade, replacing him with Brigadier Selwyn Porter, who had commanded a brigade in the Kokoda Track campaign. Unlike most reliefs of senior officers in SWPA this relief, while controversial at the time, has attracted little attention since.[35]

On 7 November 1943, Morshead became acting commander of New Guinea Force and Second Army on Mackay's departure. This became permanent on 20 January 1944. Morshead was in overall charge of the forces in New Guinea in the battles of Sattelberg, Jivevaneng, Sio and Shaggy Ridge. He was rewarded with the capture of Madang in triumph in April 1944.

Borneo Campaign

Lieutenant General Sir Leslie Morshead with General of the Army Douglas MacArthur on Labuan in June 1945

Lieutenant General Sir Leslie Morshead with General of the Army Douglas MacArthur on Labuan in June 1945

Morshead handed over command of New Guinea Force to Lieutenant General Stanley Savige on 6 May 1944 and returned to Australia, where he took Lieutenant General Iven Mackay's place as commander of the Second Army. Despite the fact that Morshead had been in command in an active area, some critics of the government had already picked up on the November announcement that Morshead would command Second Army and charged that he had been "shelved".[36]

However, this was not the end of Morshead's wartime service, just a respite. In July 1944, Morshead was appointed as commander of I Corps on the Atherton Tableland. Although nominally a lesser command, it would be the spearhead of the Australian Army in subsequent operations.[37]

In February 1945, Morshead received word that his objective would be Borneo. General of the Army Douglas MacArthur placed Morshead's I Corps under his direct command for the operation. I Corps had to make a series of landings on the East and North West coasts of the island. These were carried out with great efficiency, achieving their objectives with low casualties.

The British government proposed that British Lieutenant General Sir Charles Keightley be given command of a Commonwealth Corps for Operation Coronet but the Australian government had no intention of concurring with the appointment of an officer with no experience fighting the Japanese, and counter-proposed Morshead for the command. The war ended before the issue was resolved.[38]

Post-war life

After the war Morshead returned to civilian life, becoming the Orient Steam Navigation Company's Australian general manager on 31 December 1947. However, he continued to receive additional honours for his military service, including a further Mention in Despatches in 1947.[39] From 1950 he headed 'The Association', a secret organization prepared to oppose communist attempts at subversion. It was quietly disbanded in 1952. Morshead had had a brief connexion with a similar movement in the mid-1920s.[1]

In 1957 he was appointed chairman of a committee which reviewed the group of departments concerned with defence. The Menzies government accepted the committee's recommendation that Supply and Defence Production be amalgamated but dropped the key proposal that the Department of Defence absorb Army, Navy and Air. This was finally carried out by the Whitlam government in 1975.[40]

In later life, Morshead turned down various offers of military and diplomatic posts, as well as the governorship of Queensland.[1] Survived by his wife and daughter, Sir Leslie died of cancer on 26 September 1959 at St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney, and was cremated with Anglican rites.[1]

Memorials

Morshead Home, with Barcoo anchor, 25 pounder gun and DC-3 propeller, representing the three arms of the Australian Defence Force.

The road Morshead Drive which runs past the Royal Military College, Duntroon in Canberra, Australia is named after him. His portrait by Ivor Hele is held by the Australian War Memorial, as are his wartime papers.

In the Canberra suburb of Lyneham is the Morshead War Veterans Home, with high-dependency care and associated self-care two-bedroom houses.

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Australian Dictionary of Biography entry

- ^ Morshead: Hero of Tobruk and El Alamein, Australian Army History Unit.

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 5-7

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 11-13

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 13-14

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 18-19, 22

- ^ Bean, Volume II, The Story of ANZAC, pp. 309-316

- ^ Bean, Volume II, The Story of ANZAC, pp. 508, 517, 543, 553

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, p. 36

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 30111. pp. 5468–5475. 1 June 1917. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31684. pp. 15435–15436. 9 December 1919. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31150. pp. 1445–1446. 28 January 1919. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 74-81

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 73-74

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 87-88

- ^ Long, To Benghazi , p. 59

- ^ Long, To Benghazi , pp. 85-86, 305-310

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 35029. p. 9. 31 December 1940. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Maughan, Tobruk and El Alamein, pp. 8-10

- ^ Maughan, Tobruk and El Alamein, p. 11

- ^ Maughan, Tobruk and El Alamein, p. 10

- ^ Maughan, Tobruk and El Alamein, pp. 120-129

- ^ London Gazette: no. 37695. p. 4221. 20 August 1946. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, pp. 119-120

- ^ Maughan, Tobruk and El Alamein, pp. 380-382

- ^ London Gazette: no. 35408. p. 139. 6 January 1942. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 35397. p. 7369. 26 December 1941. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, p. 141

- ^ Johnson and Stanley, Alamein: The Australian Story, p. 262

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 35611. pp. 2851–2857. 26 June 1942. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 35794. p. 5091. 20 November 1942. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, p. 160

- ^ Gavin Long interview with Lieutenant General Frank Horton Berryman, 11 September 1956, AWM93 50/2/23/331

- ^ Coates, Bravery Above Blunder, pp. 123, 212-213

- ^ Coates, Bravery Above Blunder, 174-177, 197

- ^ "AIF Divisions being Overworked", Sydney Morning Herald 11 February 1944

- ^ Coombes, Morshead, p. 184

- ^ Horner, High Command, p. 418

- ^ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37898. p. 1085. 4 March 1947. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, pp. 43-47

References

- Bean, C. E. W. (1921). "Volume II, The Story of ANZAC: From 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation" (PDF). The Official History of Australia in the war of 1914-1918. University of Queensland Press. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/chapter.asp?volume=3.

- Coates, John (1999). Bravery Above Blunder: The 9th Australian Division at Finschhafen, Sattelberg and Sio. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195508378.

- Coombes, David (2001). Morshead: Hero of Tobruk and El Alamein. Australian Army History Series. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551398-3.

- Horner, David (1982). High Command. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-86861-076-3.

- Horner, David (2001). Making the Australian Defence Force. The Australian Centennial History of Defence. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195541197.

- Johnson, Mark; Stanley, Peter (2002). Alamein: The Australian Story. Australian Army History Series. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019551630.

- Long, Gavin (1952). To Benghazi. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/chapter.asp?volume=17.

- Maughan, Barton (1966). Tobruk and El Alamein. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Australian War Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/chapter.asp?volume=19.

- Moore, John (1976). Morshead. Haldane Publishing Co Pty Ltd, Sydney.

- A. J. Hill, 'Morshead, Sir Leslie James (1889 - 1959)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 15, Melbourne University Press, 2000, pp 423–425.

External links

- WW2DB: Biography of Morshead

- Morshead War Veterans Home

- Photo of Generals Morshead and Freyberg conferring in a shell hole in North Africa

Military offices Preceded by

Lieutenant General Sir Iven Giffard MackayGOC Second Army

1944 – 1944Succeeded by

Major General Herbert William LloydPreceded by

Lieutenant General Frank BerrymanGOC I Corps

1944 – 1945Succeeded by

Formation inactivatedPreceded by

Lieutenant General Edmund HerringGOC II Corps

1943 – 1943Succeeded by

Lieutenant General Frank BerrymanAllen • Beavis • Bennett • Berryman • Blake • Blamey • Boase • Bridgeford • Burston • Callaghan • Cannan • Chapman • Clowes • Downes • Drake-Brockman • Durrant • Eather • Herring • Jess • Lavarack • Locke • Mackay • Milford • Morshead • Morris • Murray • Northcott • Plant • Ramsay • Rankin • Robertson • Rowell • Savige • Simpson • Smart • Stantke • Steele • Steele • Stevens • Sturdee • Vasey • White • Whitelaw • WynterCategories:- 1889 births

- 1959 deaths

- Australian Anglicans

- Australian generals

- Australian military personnel of World War I

- Australian military personnel of World War II

- Cancer deaths in New South Wales

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath

- Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Australian knights

- People from Ballarat

- Recipients of the Virtuti Militari

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.