- Battle of Messines

-

Battle of Messines Part of the Western Front of the First World War

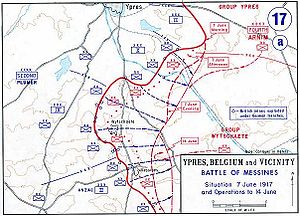

Map of the battle, depicting the front on 7 June and subsequent action until 14 June.Date 7–14 June 1917 Location Flanders, Belgium Result Decisive British victory Belligerents  United Kingdom

United Kingdom

German Empire

German EmpireCommanders and leaders  Herbert Plumer

Herbert Plumer

Alexander Godley

Alexander Godley

Alexander Hamilton-Gordon

Alexander Hamilton-Gordon

Thomas Morland

Thomas Morland Sixt von Armin

Sixt von ArminStrength 12 divisions[1]

216,000 men total5 divisions[2]

126,000 men totalCasualties and losses 17,000 [3] 25,000[4] - Messines

- Pilckem Ridge

- Langemarck

- Menin Road

- Polygon Wood

- Broodseinde

- Poelcappelle

- 1st Passchendaele

- 2nd Passchendaele

The Battle of Messines was a battle of the Western front of the First World War. It began on 7 June 1917 when the British Second Army under the command of General Herbert Plumer launched an offensive near the village of Mesen (Messines) in West Flanders, Belgium. The target of the offensive was a ridge running north from Messines village past Wytschaete village which created a natural stronghold southeast of Ypres. One of the key features of the battle was the detonation of 19 mines immediately prior to the infantry assault, a tactic which disrupted German defences and allowed the advancing troops to secure their objectives in rapid fashion. The attack was also a prelude to the much larger Third Battle of Ypres, known as Passchendaele, which began on 11 July 1917.

Contents

Background

The assault on Messines Ridge was conceived in early 1916, as Plumer sought ways to break German control of important strategic locations in the Ypres area.[5] When it became apparent that the French offensive on the River Aisne would not succeed, General Douglas Haig instructed the Second Army to undertake the operation to capture the Messines—Wytschaete Ridge,[6] to force the Germans to move troops from the front at Vimy—Arras and as the prelude to a larger assault in the Ypres sector and ordered Plumer to proceed with the attack as soon as possible.[5] The capture of Messines Ridge would give the British control of strategically important ground and flatten out the southern flank of the Ypres Salient.[7] This would reduce the manpower needed to maintain the front and reduce the German strategic and tactical advantages in the area.[8]

Mining operations

Co-ordinated by the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers, over a period beginning more than a year before the attack, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and British engineers tunnelled under the German trenches and laid 22 mines totaling 455 tonnes of ammonal explosive.[9] Several compliments were given to the military geologists who planned the tunnels. “It was said that one reason for the great success of the British operations at Messines ridge, where fifty or more mines were exploded, was the skill of the geologist who planned their location; for in some cases they were so surrounded by quicksands that the Germans could not countermine. I cannot vouch for the truthfulness of this, but, knowing the men concerned, I believe it.”[10] After the war, an examination of the lessons learned in military geology to reorganize the German Army also reviewed this incident: "Starting early in 1916 the British conducted a most extensive and persistent mining offensive against the “Wytschaete Salient”. After March 1916, they had the advice of two military geologists in this undertaking; sub-surface conditions here were especially complex: several different Tertiary and Quaternary formations with separate ground water tables made mining most troublesome, but the advice of the British geologists helped to overcome many technical difficulties. Starting from a long distance away, their sappers drifted galleries several hundred metres long (5454 m altogether) to points deep underneath the German front lines; moreover, they diverted the attention of German sappers from their deepest attack galleries by making countless secondary attacks using the upper mine galleries. Thus the military geologists on the British side proved themselves to be “indispensible and extremely valuable.”[11] To solve the problem of wet soil, the tunnels were made in the layer of "blue clay", 80–120 feet (25–30 m) below the surface.[9] The galleries dug in order to lay these mines totalled over 8,000 metres in length, and had been constructed in the face of tenacious German counter-mining efforts.[12] On several occasions, German tunnellers were within metres of large British mine "chambers". One mine was found by the Germans and the chamber was wrecked by a countermine.[13]

The largest of the 22 Messines mines was at Spanbroekmolen; the "Lone Tree Crater" formed by the blast was approximately 250 feet (80 m) in diameter and 40 feet (12 m) deep.[14] The mine consisted of 41 tons of ammonal explosive, in a chamber dug 88 feet (27 m) below ground.[14]

The evening before the attack, General Plumer remarked to his staff, "Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography."[15]

Opposing forces

The assault on a 17,000 yard front was conducted by the three corps of Plumer's British Second Army.[1] On the northern edge of the sector was British X Corps, commanded by Lietenant-General Sir Thomas Morland [16] with the 23rd, 47th, 41st Divisions and 24th Division in reserve.[2] In the centre was the British IX Corps commanded by Sir Alexander Hamilton-Gordon with 19th British, 16th Irish, 36th Ulster Divisions and 11th (Northern) Division in reserve.[2] To the southeast, Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Godley commanded the II Anzac Corps with 25th British, 1st New Zealand, 3rd Australian Divisions with 4th Australian Division in reserve.[2] II Brigade, Heavy Branch Machine-Gun Corps was in support, mainly to attack on the flanks at Dam Strasse in the north and Messines in the south,[17] while XIV Corps was held in reserve with Guards, 1st, 8th and 32nd Divisions.[18]

Opposing Plumer's Second Army was Gruppe Wijtschate, under General Von Laffert of the German Fourth Army, commanded by Friedrich Bertram Sixt von Armin.[19] To the northeast, the 204th (Wurrtemberg)[20] and 35th divisions defended Hill 60 and Battle Wood.[2] In the centre, the 2nd Division 40th (Saxon) and 3rd Bavarian Division defended the Wijschatebogen (Messines and Wytschaete ridge).[2] In the southeast, the southern banks of the River Douve were defended by the 4th Bavarian Division.[2] The German defenses relied on an "elastic" defense method; the front-lines were lightly defended, with defensive fortifications distributed up to half a mile behind the front line.[21] A captured Corps Order from Gruppe Wijtshate received by Sir Douglas Haig on 1 June read,

- 2(a) The unconditional retention of the independent strong points, Wytschaete and Messines, is of increased importance for the domination of the whole Wytschaete salient. These strong points must therefore not fall even temporarily into the enemy's hands.[22]

while the British plan envisaged an advance to the 'Oosttaverne Line' a maximum depth of 3,000 yards.[23]

Battle

The plan for the attack on Messines Ridge called for heavy artillery fire before zero hour. At 03:00am, the mines would be detonated, followed by a frontal assault of nine infantry divisions aimed at securing the ridge.[24] In the week before the attack, some 2,230 guns bombarded the German trenches and conducted counter-battery fire against the 630 German guns and howitzers (236 field guns, 108 field howitzers, 54 100mm-130mm guns, 24 150 mm guns, 174 medium howitzers, 40 heavy howitzers and four heavy 210mm and 240mm guns) with 3,561,530 shells.[21][25] Equipped with new highly detailed maps of the battlefield, British artillery succeeded in destroying close to 90% of the German field-gun positions on Messines Ridge.[21]The German Official Account records that by the morning of 7 June Gruppe Wytschaete had lost a quarter of its field artillery and half of its heavy artillery.[26]

The 'blue line' was to be occupied by zero + 1.40 with a two hour pause. At zero + 3.40 the advance to the 'black line' would begin and consolidation was to start by zero + 5. Fresh troops would pass through to the attack on the Oosttaverne line at zero + 10. As soon as the black line was captured all guns were to be emplyed to bombard the Oosttaverne Line, on counter-battery fire and on a standing barrage before the black line. All tanks still operational were to join with the 24 held in reserve to support the infantry advance to the Oosttaverne line.[27]

Detonation of the mines

At 02:50am on 7 June, the artillery bombardment ceased. Expecting an immediate infantry assault, German defenders returned to their forward positions.[28] At 3:10am, the mines were detonated, killing approximately 10,000 German soldiers and destroying most of the fortifications on the ridge, as well as the village of Messines.[28] Reports were made that the shockwave from the explosion was heard as far away as London and Dublin.[29] To make matters worse for the Germans, the explosions occurred while the front line troops were being relieved, meaning both groups (relieving and relieved) were caught in the blasts.[29]

While determining the power of explosions is difficult, the 1917 Messines mines detonation was probably the largest planned explosion in history prior to the Trinity atomic weapon test in July 1945 and the largest non-nuclear planned explosion before the British explosive efforts on the Heligoland Islands in April 1947. With approximately 10,000 killed, the Messines detonation is history's deadliest non-nuclear man-made explosion.

Artillery plan

Artillery fire resumed at the same moment as the explosion of the mines. The fireplan called for most of the 18-pounder field guns to fire a creeping barrage of shrapnel immediately ahead of the advance, while the other field guns and 4.5 inch howitzers fired a standing barrage some 700 yards (640 m) further ahead. The standing barrage was aligned with German positions and lifted to the next target when the advance got within 400 yards (370 m) of it. As each objective was taken by the infantry, the creeping barrage would pause 150 to 300 yards (140 to 270 m) ahead of them and become a standing barrage, protecting the newly gained positions from counterattack while the infantry consolidated. During this time the pace of fire slackened to one round per gun a minute, enabling the guns and the crews a respite, before resuming full intensity as the barrage moved on. The heavy and super-heavy artillery fired on German rear areas and over 700 machine guns participated in the barrage, firing over the heads of the advancing troops.[30]

Assault

Immediately after the mine explosions and closely following the creeping artillery barrage, British, Australian and New Zealand troops from the II ANZAC Corps, IX Corps and X Corps advanced on the Messines salient from three sides.[19] The front lines were overrun without opposition. German troops surrendered "in droves"[31] and the first objectives had been secured almost entirely within three hours.[31] Advancing on the southern flank, the New Zealand Division captured the village of Messines proper, despite intricate layers of fortifications beyond the front line.[19]

In the centre, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) further north, the 36th (Ulster) Division and 16th (Irish) Division advanced in tandem, the Irish capturing the village of Wytschaete and pushing forward to secure their objectives.[19] Many considered this joint effort to be of considerable political significance, given the turmoil in Ireland at the time.[19] The Irish Nationalist Party MP Major William Redmond was fatally wounded in this action.[32] The most serious resistance was in the northern sector, where the 47th (1/2nd London) Division had to navigate the Ypres-Comines canal. This obstacle slowed the advance considerably but the Londoners had secured all their objectives by mid-morning and the goals of the first phase were achieved by 10:00am at all points on the line of attack.[31]

Once the first objectives were secured, more than forty batteries of artillery were brought forward to support the second phase of the attack.[19] Bombardment continued for several hours and at approximately 3:00pm the reserve divisions, supported by tanks, advanced towards the second line of objectives.[19] In just over an hour, all these were secured.[19] At 11:00AM, German troops counterattacked at several points along the new British lines. Although British troops had had very little time to consolidate their positions, the German attacks were easily repulsed and ultimately resulted in further territorial gains.[33] Heavy British artillery bombardments on 10 June meant that further counterattacks never materialized.[4]

There were four Victoria Crosses awarded during the battle, two in the Australian 3rd Division (to Private John Carroll and Captain Robert Cuthbert Grieve), one in the New Zealand Division (to Lance-Corporal Samuel Frickleton) and one in the 25th Division (to Private William Ratcliffe).

Aftermath

The operation was a great success. Meticulously planned and well executed, the assault secured its objectives in less than twelve hours, took 7,354 prisoners,[34]48 guns, 218 machine-guns and 60 trench mortars for a relatively modest (by WWI standards) 24,562 casualties[35], 1 - 12 June.[34] The German Official Account gives 23,000 casualties (less 'wounded likely to return to duty within a reasonable time' which the British Official Historian considered to amount to another 30%, although this has been disputed ever since) including 10,000 missing, 21 May - 10 June.[36] The combination of tactics proven in other sectors—notably the use of mines, creeping barrages and small-unit tactics—allowed for surprise and rapid infantry advances.[4] The offensive also secured the southern end of the Ypres salient in preparation for the offensive in that area.[37]

Although the operation was successful, it had the effect of inflating expectations for the Passchendaele offensive. While Messines led Haig and other British commanders to believe that success could be had relatively cheaply in the main offensive as well, the circumstances of the operations were substantially different and attempts to apply similar tactics would result in a general failure.[38]

Two of the 21 mines did not go off on time.[13] On 17 July 1955[contradictory], lightning set off one of these mines, killing a cow. The 21st mine—the mine abandoned as a result of its discovery by German counter-miners—is believed to have been found but no attempt has been made to remove it.[28]

See also

- Western Front (World War I)

- Third Battle of Ypres

- Ronald Skirth, British pacifist artilleryman, vowed not to take another human life after the Battle of Messines

Notes

- ^ a b Wolff, p. 95

- ^ a b c d e f g Wolff, p. 98

- ^ http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/messines.htm

- ^ a b c Groom, p. 169

- ^ a b Mallett, 115

- ^ Edmonds, J. ibid, Appendix VIII (2nd Army Operations order No 1, 10 May 1917), p.416

- ^ Wolff, p. 87

- ^ Australian Government Official History, 588

- ^ a b Wolff, p. 88.

- ^ Cleland, Herdman F. 1918. “The Geologist in War Time: Geology on the Western Front.” Economic Geology. Volume 13, pp. 145–6.

- ^ Bűlow, Kurd von, 1899–, Kranz, Walter, 1873–, Sonne, Erich, Burre, Otto, Dienemann, Wilhelm. 1938. Wehrgeologie. English translation, pp. 103–4. USGS Library.

- ^ Liddell Hart, p. 331.

- ^ a b Wolff, p. 92

- ^ a b Mallett, p. 116.

- ^ Messines, First World War.com, http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/messines.htm.

- ^ Terraine, J. The Road to Passchendaele, p. 118.

- ^ Edmonds, J. ibid, Appendix X, p. 419.

- ^ Edmonds, OH 1917 II, Appendix VIII, p. 417.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Liddell Hart, p. 334.

- ^ Sheldon, J. The German Army at Passchendaele pp. 1-3. (2007)

- ^ a b c Groom, p. 165

- ^ Terraine, J. ibid, p. 118.

- ^ Edmonds, ibid, Appendix IX (Second Army Operation Order No 2, 19 May 1917), p. 418.

- ^ Hart, p. 332

- ^ Edmonds, J. ibid, p. 49 fn 2.

- ^ xii, p. 454 in Edmonds, ibid, p. 49 fn 2.

- ^ Edmonds,J. ibid, pp. 419-420.

- ^ a b c Battle of Messines on First World War.com

- ^ a b Groom, p. 167

- ^ Steel & Hart pp 45 & 54

- ^ a b c Wolff, p. 101

- ^ Casualty details from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- ^ Liddell Hart, p. 336.

- ^ a b Wolff, p. 102

- ^ Edmonds, J OH 1917 II p.87

- ^ Edmonds,ibid p. 88.

- ^ Wolff, p. 103

- ^ Liddell Hart, 339–340.

References

- Burke, Tom, MBE; "A Guide to the Battlefield of Wijtschate: June 1917", The Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association (pub June 2007); ISBN 0-9550418-1-3

- Groom, Winston (2002). A Storm in Flanders, the Ypres Salient, 1914–1918. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-842-5

- Keegan, John; The First World War New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999

- Liddell Hart, B.H. The Real War 1914–1918. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1930

- Steel, Nigel; Hart, Peter (2001). Passchendaele—The Sacrificial Ground. Cassel. pp. 45 & 54. ISBN 9781407214672.

- Stokesbury, James L; A short history of World War I. New York: Perennial, 1981

- Strachan, Hew; The First World War. New York: Viking, 2003

- Wolff, Leon; In Flanders Fields, Passchendaele 1917.

Further reading

- Bean, C.E.W.; "The Battle of Messines", Chapter 15 in The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Vol IV, The AIF in France: 1917, 1941.

- Passingham, Ian; Pillars of Fire: the Battle of Messines Ridge, June 1917, 1998.

- Stewart, H; "The Battle of Messines", Chapter V in The New Zealand Division 1916–1919: A Popular History based on Official Records, 1921.

External links

- No Man's Land The European Group for Great War Archaeology, "Plug Street Project" : Report on Archaeological Excavations in St Yvon area. 2007

- The Plugstreet Archaeology Project [1]

- The Battle for Messines Ridge

- First World War.com - A more detailed overview of the battle with links to present day pictures of the battlefield

- An account of the experiences of an ordinary soldier at Messines ridge, as recounted in his letters home

- Battle for Messines (NZHistory.net.nz) includes film and interactive showing the creeping barrage

- Farmer who is sitting on a bomb - The Daily Telegraph

- WWI underground: Unearthing the hidden tunnel war BBC News (10 June 2011)

Categories:- 1917 in Belgium

- 20th-century explosions

- Battles of the Western Front (World War I)

- Battles of World War I involving Australia

- Battles of World War I involving Germany

- Battles of World War I involving New Zealand

- Battles of World War I involving the United Kingdom

- Conflicts in 1917

- World War I mines

- Ypres Salient

- Tunnel warfare

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.