- Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

-

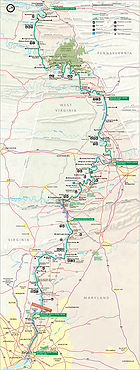

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal, and occasionally referred to as the "Grand Old Ditch,"[by whom?] operated from 1831 until 1924 parallel to the Potomac River in Maryland from Cumberland, Maryland to Washington, D.C. The total length of the canal is about 184.5 miles (296.9 km). The elevation change of 605 ft (184 m) was accommodated with 74 canal locks. To enable the canal to cross relatively small streams, over 150 culverts were built. The crossing of major streams required the construction of 11 aqueducts (10 of which remain). The canal also extends through the 3,118 ft (950 m) Paw Paw Tunnel. The principal cargo was coal from the Allegheny Mountains. The canal way is now maintained as a park, with a linear trail following the old towpath, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.

Contents

History

Early river projects

After the American Revolutionary War, George Washington was the chief advocate of using waterways to connect the Eastern Seaboard to the Great Lakes and the Ohio River.[1] Washington founded the Potowmack Company in 1785 to make navigability improvements to the Potomac River. The Patowmack Company built a number of skirting canals around the major falls including the Patowmack Canal in Virginia. When completed, it allowed boats and rafts to float downstream towards Georgetown. Going upstream was a bit harder. Slim boats could be slowly poled upriver. The completion of the Erie Canal worried southern traders that their business might be threatened by the northern canal; plans for a canal linking the Ohio and Chesapeake were drawn up as early as 1820.

Building the canal

In 1824, the holdings of the Patowmack Company were ceded to the Chesapeake and Ohio Company. Benjamin Wright, formerly Chief Engineer of the Erie Canal, was named Chief Engineer of this new effort, and construction began with a groundbreaking ceremony on July 4, 1828 by President John Quincy Adams.

The narrow strip of available land along the Potomac River from Point of Rocks to Harpers Ferry caused a legal battle between the C&O Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) in 1828 as both sought to exclude the other from its use.[2] Following a Maryland state court battle involving Daniel Webster and Roger B. Taney, the companies later compromised to allow the sharing of the right of way.[2]

The canal initially connected to the Potomac River on the east side of Georgetown by joining Rock Creek east of Lock 1, 0.3 miles (0.5 km) upstream of the Tidewater Lock, whose remnants still exist to the west of the mouth of the creek.[3][4] In 1831 the first section opened from Georgetown to Seneca, Maryland.[5] In 1833 the canal opened to Harpers Ferry, and at the Georgetown end it was extended 1.5 miles (2.4 km) eastward to Tiber Creek, near the western terminus of the Washington City Canal.[6][7][8] A lock keeper's house at the eastern end of this "Washington Branch" of the C&O Canal remains at the southwest corner of Constitution Avenue and 17th Street, N.W., at the edge of the National Mall in Washington, D.C.[9][10]

In 1836, the canal was used as a Star Route for the carriage of mails from Georgetown to Shepherdstown using canal packets. The contract was held by Albert Humrickhouse at $1,000 per annum for a daily service of 72 book miles. The canal approached Hancock, Maryland by 1839.[5] In 1843, the Potomac Aqueduct Bridge was constructed near the present-day Francis Scott Key Bridge to connect the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to the Alexandria Canal which led to Alexandria, Virginia.[11] By the time the canal reached Cumberland in 1850, it had already been rendered obsolete; the B&O Railroad had reached Cumberland eight years previously.[12] Debt-ridden, the company dropped its plan to continue construction of the next 180 miles (290 km) of the canal into the Ohio valley.[13]

In the 1870s, a canal inclined plane was built two miles (3 km) upriver from Georgetown, so that boats whose destination was downriver from Washington could bypass the congestion in Georgetown.[14] The inclined plane was dismantled after a major flood in 1889 when ownership of the canal transferred to the B&O Railroad, which operated the canal to prevent its right of way (particularly at Point of Rocks) from falling into the hands of the Western Maryland Railway.[2] Operations ceased in 1924 after another flood damaged the canal.

The planned C&O Canal route to navigable waters of the Mississippi watershed would have followed the North Branch Potomac River west from Cumberland to the Savage River. Via the Savage, the canal would have crossed the Eastern Continental Divide at the gap between the Savage and Backbone Mountains near where present day O'Brien Road intersects Maryland Route 495, then via the valley of present day Deep Creek Lake, followed the Youghiogheny River to navigable waters.[citation needed]

National park

In 1938 the abandoned canal was obtained from the B&O by the United States in exchange for a loan from the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation.[2] The government planned to restore it as a recreation area. Although the lower 22 miles (35 km) of the canal were repaired and rewatered, the project was halted when the United States entered World War II and resources were needed elsewhere. After the war, Congress expressed interest in developing the canal and towpath as a parkway. However, the idea of turning the canal over to automobiles was opposed by some, including United States Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas. In March 1954, Douglas led an eight-day hike of the towpath from Cumberland to D.C.[2] Although 58 people participated in one part of the hike or another, only nine men, including Douglas, hiked the full 184.5 miles (297 km). Popular response to and press coverage of the hike turned the tide against the parkway idea and, on January 8, 1971, the canal was designated a National Historical Park.

Presently the park includes nearly 20,000 acres (80 km²) and receives over 3 million recorded visits each year. Flooding continues to threaten historical structures on the canal and attempts at restoration. The Park Service has re-watered portions of the canal, but the majority of the canal does not have water in it.

Today the park is a popular getaway for Washington residents. The towpath is popular with bikers and joggers. Fishing and boating are popular in the re-watered portions, and whitewater kayakers tackling the world class rapids of the Potomac sometimes use the canal to shuttle upstream. The park offers rides on two reproduction canal boats, the Georgetown and the Charles F. Mercer, during the spring, summer and autumn. The boats are pulled by mules and park rangers in historical dress work the locks and boat while presenting a historical program.

Locks and engineering

To build the canal, the C&O Canal Company utilized a total of 74 lift locks that raised the canal from sea level at Georgetown to 610 feet (190 m) at Cumberland.[13] Eleven stone aqueducts were built to carry the canal over the Potomac's tributaries. In addition, seven dams were built to supply water to the canal, waste weirs to control water flow, and 200 culverts to carry roads and streams underneath the canal. An assortment of lockhouses, bridges, and stop gates were also constructed along the canal's path.[13]

One of the most impressive engineering features of the canal is the Paw Paw Tunnel, which runs for 3,118 feet (950 m) under a mountain.[13] Built to save six miles (10 km) of construction around the obstacle, the 3/4-mile tunnel used over six million bricks. The tunnel took almost twelve years to build; in the end, the tunnel was only wide enough for single lane traffic.[15]

Points of interest

- East of Mile 000: Lock Keeper's House at eastern end of Washington Branch of C&O Canal.[10]38°52′13.6482″N 77°0′55.6878″W / 38.870457833°N 77.015468833°W

- Mile 000: Tidewater Lock[4]

- Mile 000: Rock Creek Park38°57′10″N 77°2′30″W / 38.95278°N 77.04167°W

- Mile 000: C&O Canal Monument

- Mile 000: Lock 1[3]38°54′13.5504″N 77°3′25.9272″W / 38.903764°N 77.057202°W

- Mile 000: Georgetown, Washington, D.C. 38°53′59″N 77°3′27.5″W / 38.89972°N 77.057639°WCoordinates: 38°53′59″N 77°3′27.5″W / 38.89972°N 77.057639°W and Georgetown Visitor Center

38°54′14.5″N 77°3′31″W / 38.904028°N 77.05861°W

- Mile 000: Potomac Heritage Trail - on Virginia side of river. (Bikes can use it below Francis Scott Key Bridge.)

- Mile 001: Abutment and former canal bed of Potomac Aqueduct Bridge[11]

- Mile 001: Capital Crescent Trail

- Mile 002: Inclined Plane[14]

- Mile 007: Glen Echo Park (Maryland) and Lock 7 38°57′52″N 77°8′20″W / 38.96444°N 77.13889°W

- Mile 014: Billy Goat Trail at Great Falls, Great Falls Tavern 39°0′1″N 77°14′54″W / 39.00028°N 77.24833°W

- Mile 016: Swain's Lock at Lock 21, Potomac, Md

- Mile 020: Pennyfield Lock 39°3′13.6″N 77°17′20″W / 39.053778°N 77.28889°W

- Mile 022: Violette’s Lock (Lock 23) The canal has water in it from here south. 39°4′1″N 77°19′43″W / 39.06694°N 77.32861°W

- Mile 022: Riley's Lock/Seneca Creek Aqueduct 39°4′7.5″N 77°20′27″W / 39.06875°N 77.34083°W

- Mile 026: Dierssen Wildlife Management Area & McKee-Beshers Wildlife Management Area

- Mile 035: Poolesville, Maryland

- Mile 035: White's Ferry 39°9′17″N 77°31′2″W / 39.15472°N 77.51722°W

- Mile 042: Monocacy Aqueduct 39°13′25″N 77°27′7″W / 39.22361°N 77.45194°W

- Mile 048: Point of Rocks, Maryland 39°16′25″N 77°32′30″W / 39.27361°N 77.54167°W

- Mile 055: Brunswick, Maryland 39°18′41″N 77°37′50″W / 39.31139°N 77.63056°W

- Mile 058: Appalachian Trail

- Mile 060: Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 39°19′31″N 77°44′36″W / 39.32528°N 77.74333°W

- Mile 073: Ferry Hill, Maryland

- Mile 073: Shepherdstown, West Virginia39°25′55″N 77°48′22″W / 39.43194°N 77.80611°W

- Mile 073: Sharpsburg, Maryland 39°27′28″N 77°44′58″W / 39.45778°N 77.74944°W

- Mile 099: Williamsport, Maryland39°35′55″N 77°49′6″W / 39.59861°N 77.81833°W

- Mile 107: Dam No. 539°36′22″N 77°55′23″W / 39.60611°N 77.92306°W

- Mile 110: Four Locks - Once a thriving community of homes and businesses supporting the canal.

- Mile 110.4: McCoy's Ferry - Campground and historic American Civil War crossing

- Mile 112: Fort Frederick State Park; Western Maryland Rail Trail begins

- Mile 124: Hancock, Maryland

- Mile 124: Rt. 522 Bridge to Berkeley Springs, West Virginia; Western Maryland Rail Trail diverges

- Mile 140: Little Orleans, Maryland

- Mile 151: Paw Paw Tunnel

- Mile 151: Paw Paw, West Virginia

- Mile 165: Oldtown, Maryland

- Mile 184: Cumberland, Maryland

- Mile 184: Canal Place

- Mile 184: Western Maryland Scenic Railroad

See also

References

- ^ Hahn, 1.

- ^ a b c d e Lynch, John A.. "Justice Douglas, the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, and Maryland Legal History". University of Baltimore Law Forum 35 (Spring 2005): 104–125

- ^ a b Coordinates of Lock 1: 38°54′14″N 77°03′27″W / 38.9039585°N 77.0574778°W

- ^ a b Coordinates of tidewater lock: 38°54′00″N 77°03′28″W / 38.8998673°N 77.0578507°W

- ^ a b Hahn, 6.

- ^ ""The Canal Connection" marker". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. http://www.hmdb.org/Marker.asp?Marker=211. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ "Washington City Canal: Plaque beside the Lockkeeper's House marking the former location of in Washington, D.C.". dcMemorials.com: Memorials, monuments, statues & other outdoor art in the Washington D.C. area & beyond, by M. Solberg. http://dcmemorials.com/index_indiv0001032.htm. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ ""The Washington City Canal" marker". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. http://www.hmdb.org/Marker.asp?Marker=210. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ ""Lock Keeper’s House" marker". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=209. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ a b Coordinates of lock keeper's house: 38°53′31″N 77°02′23″W / 38.8919305°N 77.0397498°W

- ^ a b Coordinates of abutment and canal bed of Potomac Aqueduct Bridge: 38°54′16″N 77°04′13″W / 38.904328°N 77.0704074°W

- ^ Mackintosh, 1.

- ^ a b c d Hahn, 7.

- ^ a b Coordinates of inclined plane: 38°54′28″N 77°05′29″W / 38.9078825°N 77.0912723°W

- ^ National Park Service, "The Paw Paw Tunnel is 3118 feet (950 m) long and is lined with over six million bricks. The 3/4 mile long tunnel saved the canal builders almost six miles (10 km) of construction along the Paw Paw bends of the Potomac River. It took twelve years to build and was only wide enough for single lane traffic."

General references

-

Camagna, Dorothy (2006). The C&O Canal: From Great National Project to National Historical Park. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Belshore Publications. ISBN 0-977044-90-4.

-

Hahn, Thomas (1984). The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal: Pathway to the Nation's Capital. Metuchen, New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-1732-2.

-

Mackintosh, Barry (1991). C&O Canal: The Making of A Park. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, Department of the Interior.

-

National Park Service (2006-08-08). "C&O Canal Educational Programs: Lessons Page". United States Department of the Interior. http://www.nps.gov/choh/forteachers/aboutthislesson.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

Further reading

- Life on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, 1859 [York, Pa. : American Canal and Transportation Center, 1975]

- Achenbach, Joel. The Grand Idea: George Washington's Potomac and the Race to the West, Simon and Schuster, 2004.

- Blackford, John, 1771-1839. Ferry Hill Plantation journal: life on the Potomac River and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, 4 January 1838-15 January 1839 2d ed. Shepherdstown, W. Va. : [American Canal and Transportation Center], 1975.

- Cotton, Robert. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Through the Lens of Sir Robert Cotton

- Fradin, Morris. Hey-ey-ey, lock! Cabin John, Md., See-and-Know Press, 1974

- Gutheim, Frederick. The Potomac. New York: Rinehart and Co., 1949.

- Guzy, Dan. Navigation on the Upper Potomac and Its Tributaries. Western Maryland Regional Library, 2011

- Hahn, Thomas F. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Lock-Houses and Lock-Keepers.

- Hahn, Thomas F. Towpath Guide to the C&O Canal: Georgetown Tidelock to Cumberland. Shepherdstown, WV: American Canal and Transportation Center, 1985.

- High, Mike. The C&O Canal Companion, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Kapsch, Robert and Kapsch, Elizabeth Perry. Monocacy Aqueduct on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Medley Press, 2005.

- Kapsch, Robert. The Potomac Canal, George Washington and the Waterway West.Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press, 2007.

- Kytle, Elizabeth. Home on the Canal, Cabin John, Md.: Seven Locks Press, c. 1983.

- Martin, Edwin. A Beginner's Guide to Wildflowers of the C and O Towpath, 1984.

- Mulligan, Kate. Canal Parks, Museums and Characters of the Mid-Atlantic, Wakefield Press, Washington, DC, 1999.

- Mulligan, Kate. Towns along the Towpath, 1997. (Available from C &O Association) Here is Chapter 3 about Seneca.

- National Park Service, Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Washington, DC: NPS Division of Publications, 1991.

- Rada, James Jr. Canawlers, Legacy Press, 2001.

- Southworth, Scott, et al. Geology of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park and Potomac River Corridor, District of Columbia, Maryland, West Virginia, and Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1691, 2008.

External links

- Official National Park Service Site

- The Building of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Jack Rottier photographs and papers of the C and O Canal Online Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Estelle and Melvin Gelman Library, The George Washington University.

- The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

- GPS Landmark Coordinates along the C&O Canal

- C&O Canal Bicycling Guide

- A Virtual Tour of the C&O Canal

- Another Virtual Tour of the C&O Canal

- C&O Canal Association

- All About the C&O

- The economic impact of the C&O Canal on canal communities in Washington County, Maryland

- Thomas Hahn Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Collection Finding Aid, Special Collections Research Center, Estelle and Melvin Gelman Library, The George Washington University

Categories:- Canals in Maryland

- Canals in Washington, D.C.

- Chesapeake Bay Watershed

- Long-distance trails in the United States

- Potomac River Watershed

- Parks in Cumberland, MD-WV-PA

- Buildings and structures in Cumberland, Maryland

- History of Cumberland, MD-WV-PA

- Transportation in Cumberland, MD-WV-PA

- Georgetown, Washington, D.C.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.