- Chemerin

-

Retinoic acid receptor responder (tazarotene induced) 2 Identifiers Symbols RARRES2; HP10433; TIG2 External IDs OMIM: 601973 MGI: 1918910 HomoloGene: 2167 GeneCards: RARRES2 Gene Gene Ontology Molecular function • molecular_function

• receptor bindingCellular component • cellular_component

• extracellular region

• extracellular matrixBiological process • retinoid metabolic process

• in utero embryonic development

• positive regulation of macrophage chemotaxis

• embryonic digestive tract development

• brown fat cell differentiationSources: Amigo / QuickGO RNA expression pattern

More reference expression data Orthologs Species Human Mouse Entrez 5919 71660 Ensembl ENSG00000106538 ENSMUSG00000009281 UniProt Q99969 Q9DD06 RefSeq (mRNA) NM_002889 NM_027852.2 RefSeq (protein) NP_002880 NP_082128.1 Location (UCSC) Chr 7:

150.04 – 150.04 MbChr 6:

48.52 – 48.52 MbPubMed search [1] [2] Chemerin, also known as retinoic acid receptor responder protein 2 (RARRES2), tazarotene-induced gene 2 protein (TIG2), or RAR-responsive protein TIG2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the RARRES2 gene.[1][2][3]

Contents

Function

Retinoids exert biologic effects such as potent growth inhibitory and cell differentiation activities and are used in the treatment of hyperproliferative dermatological diseases. These effects are mediated by specific nuclear receptor proteins that are members of the steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily of transcriptional regulators. RARRES1, RARRES2 (this gene), and RARRES3 are genes whose expression is upregulated by the synthetic retinoid tazarotene. RARRES2 is thought to act as a cell surface receptor.[3]

Chemerin is a chemoattractant protein that acts as a ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor CMKLR1 (also known as ChemR23). Chemerin is a 14 kDa protein secreted in an inactive form as prochemerin and is activated through cleavage of the C-terminus by inflammatory and coagulation serine proteases.[4]

Chemerin was found to stimulate chemotaxis of dendritic cells and macrophages to the site of inflammation.[5]

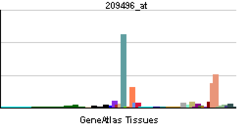

In humans, chemerin mRNA is highly expressed in white adipose tissue, liver and lung while its receptor, CMKLR1 is predominantly expressed in immune cells as well as adipose tissue.[6] Because of its role in adipocyte differentiation and glucose uptake, chemerin is classified as an adipokine.

Role as an adipokine

Chemerin has been implicated in autocrine / paracrine signaling for adipocyte differentiation and also stimulation of lipolysis.[6][7] Studies with 3T3-L1 cells have shown chemerin expression is low in pre-differentiated adipocytes[6] but its expression and secretion increases both during and after differentiation in vitro. Genetic knockdown of chemerin or its receptor, CMKLR1 impairs differentiation into adipocytes, and reduces the expression of GLUT4 and adiponectin, while increasing expression of IL-6 and insulin receptor. Furthermore, post-differentiation knockdown of chemerin reduced GLUT4, leptin, adiponectin, perilipin, and reduced lipolysis, suggesting chemerin plays a role in metabolic function of mature adipocytes.[7] Studies using mature human adipocytes, 3T3-L1 cells, and in vivo studies in mice showed chemerin stimulates the phosphorylation of the MAPKs, ERK1, and ERK2, which are involved in mediating lipolysis.[7]

Studies in mice have shown neither chemerin nor CMKLR1 are highly expressed in brown adipose tissue, indicating that chemerin plays a role in energy storage rather than thermogenesis.2

Role in obesity and diabetes

Given chemerin’s role as a chemoattractant and a recent finding macrophages have been implicated in chronic inflammation of adipose tissue in obesity.[8] This suggests chemerin may play an important in the pathogenesis of obesity and insulin resistance.

Studies in mice found that feeding mice a high-fat diet, resulted in increased expression of both chemerin and CMKLR1.[2] In humans, chemerin levels are not significantly different between individuals with normal glucose tolerance and individuals with type II diabetes. However, chemerin levels show a significant correlation with body mass index, plasma triglyceride levels and blood pressure.[4]

Interestingly, it was found incubation of 3T3-L1 cells with recombinant human chemerin protein facilitated insulin-stimulated glucose uptake.[9] This suggests chemerin plays a role in insulin sensitivity and may be a potential therapeutic target for treating type II diabetes.[4]

References

- ^ Duvic M, Nagpal S, Asano AT, Chandraratna RA (Sep 1997). "Molecular mechanisms of tazarotene action in psoriasis". J Am Acad Dermatol 37 (2 Pt 3): S18-24. PMID 9270552.

- ^ a b Roh SG, Song SH, Choi KC, Katoh K, Wittamer V, Parmentier M, Sasaki S (Sep 2007). "Chemerin--a new adipokine that modulates adipogenesis via its own receptor". Biochem Biophys Res Commun 362 (4): 1013–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.104. PMID 17767914.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: RARRES2 retinoic acid receptor responder (tazarotene induced) 2". http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=5919.

- ^ a b c Zabel BA, Allen SJ, Kulig P, Allen JA, Cichy J, Handel TM, Butcher EC (October 2005). "Chemerin activation by serine proteases of the coagulation, fibrinolytic, and inflammatory cascades". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (41): 34661–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M504868200. PMID 16096270.

- ^ Wittamer V, Franssen JD, Vulcano M, Mirjolet JF, Le Poul E, Migeotte I, Brézillon S, Tyldesley R, Blanpain C, Detheux M, Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Vassart G, Parmentier M, Communi D (October 2003). "Specific recruitment of antigen-presenting cells by chemerin, a novel processed ligand from human inflammatory fluids". J. Exp. Med. 198 (7): 977–85. doi:10.1084/jem.20030382. PMC 2194212. PMID 14530373. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2194212.

- ^ a b c Bozaoglu K, Bolton K, McMillan J, Zimmet P, Jowett J, Collier G, Walder K, Segal D (October 2007). "Chemerin is a novel adipokine associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome". Endocrinology 148 (10): 4687–94. doi:10.1210/en.2007-0175. PMID 17640997.

- ^ a b c Goralski KB, McCarthy TC, Hanniman EA, Zabel BA, Butcher EC, Parlee SD, Muruganandan S, Sinal CJ (September 2007). "Chemerin, a novel adipokine that regulates adipogenesis and adipocyte metabolism". J. Biol. Chem. 282 (38): 28175–88. doi:10.1074/jbc.M700793200. PMID 17635925.

- ^ Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H (December 2003). "Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance". J. Clin. Invest. 112 (12): 1821–30. doi:10.1172/JCI19451. PMC 296998. PMID 14679177. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=296998.

- ^ Takahashi M, Takahashi Y, Takahashi K, Zolotaryov FN, Hong KS, Kitazawa R, Iida K, Okimura Y, Kaji H, Kitazawa S, Kasuga M, Chihara K (March 2008). "Chemerin enhances insulin signaling and potentiates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes". FEBS Lett. 582 (5): 573–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2008.01.023. PMID 18242188.

Further reading

- Nagpal S, Patel S, Jacobe H, et al. (1997). "Tazarotene-induced gene 2 (TIG2), a novel retinoid-responsive gene in skin.". J. Invest. Dermatol. 109 (1): 91–5. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12276660. PMID 9204961.

- Yokoyama-Kobayashi M, Yamaguchi T, Sekine S, Kato S (1999). "Selection of cDNAs encoding putative type II membrane proteins on the cell surface from a human full-length cDNA bank.". Gene 228 (1-2): 161–7. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00004-9. PMID 10072769.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences.". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=139241.

- Scherer SW, Cheung J, MacDonald JR, et al. (2003). "Human chromosome 7: DNA sequence and biology.". Science 300 (5620): 767–72. doi:10.1126/science.1083423. PMC 2882961. PMID 12690205. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2882961.

- Hillier LW, Fulton RS, Fulton LA, et al. (2003). "The DNA sequence of human chromosome 7.". Nature 424 (6945): 157–64. doi:10.1038/nature01782. PMID 12853948.

- Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, et al. (2004). "Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs.". Nat. Genet. 36 (1): 40–5. doi:10.1038/ng1285. PMID 14702039.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, et al. (2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC).". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=528928.

- Vermi W, Riboldi E, Wittamer V, et al. (2005). "Role of ChemR23 in directing the migration of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymphoid organs and inflamed skin.". J. Exp. Med. 201 (4): 509–15. doi:10.1084/jem.20041310. PMID 15728234.

- Wittamer V, Bondue B, Guillabert A, et al. (2005). "Neutrophil-mediated maturation of chemerin: a link between innate and adaptive immunity.". J. Immunol. 175 (1): 487–93. PMID 15972683.

Categories:- Human proteins

- Proteins

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.