- Kermanshah

-

For other uses, see Kermanshah (disambiguation).

Kermanshah

هلشي

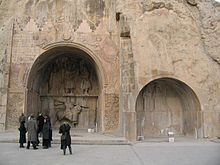

Kirmaşan کرماشان— city — Monuments of Taq-Bostan, carved 4th–6th A.D Coordinates: 34°18′51″N 47°03′54″E / 34.31417°N 47.065°ECoordinates: 34°18′51″N 47°03′54″E / 34.31417°N 47.065°E Country  Iran

IranProvince Kermanshah County Kermanshah Bakhsh Central Population (2006) – Total 784,602 Time zone IRST (UTC+3:30) – Summer (DST) IRDT (UTC+4:30) Area code(s) 0831 Kermanshah (Kurdish: کرماشان Kirmaşan، Persian: کرمانشاه Kermānshāh, also Romanized as Kermânsâh; also known as Bahtaran, Bākhtarān, Kermānshāhān , and Qahremānshahr)[1] is a city in and the capital of Kermanshah Province, Iran. At the 2006 census, its population was 784,602, in 198,117 families.[2]

The overwhelming majority of Kermanshahi people are Shi'a Muslims. Kermanshah is populated by both ethnic Persians and Shia Kurdish people and both Kermanshahi Kurdish and Kermanshahi Persian languages are spoken in the city. But today only the older generation speak Kermanshahi Kurdish and Kermanshahi Persian and the majority of the citys inhabitants speak Standard Persian which is based on the dialect/accent of Tehran.[3]

Kermanshah is located 525 km from Tehran in the western part of Iran. Kermanshah has a moderate and mountainous climate. [4] [5][6][7][8][9] The religion of most of the people is Shia Islam. Small numbers of Yarsan, Bahá'ís, Jews, and Armenians also live in Kermanshah.

Contents

History

Given its antiquity, attractive landscapes and rich culture, Kermanshah is considered as one of the cradles of prehistoric cultures such as Neolithic villages. According to archaeological surveys and excavation, Kermanshah area has been occupied by prehistoric people since the Lower Paleolithic period, and continued to later Paleolithic periods till late Pleistocene period. The Lower Paleolithic evidence consists of some handaxes found in the Gakia area to the east of the city. The Middle Paleolithic remains have been found in the northern vicinity of the city in Tang-e Kenesht and near Taq-e Bostan. The known Paleolithic caves in this area are Warwasi, Kobeh, and Do-Eshkaft. The region was also one of the first places in which human settlements including Asiab, Qazanchi, Tappeh Sarab, Chia Jani, and Ganj-Darreh were established between 8,000-10,000 years ago. This is about the same time that the first potteries pertaining to Iran were made in Ganj-Darreh, near present-day Harsin. In May 2009, based on a research conducted by the University of Hamedan and UCL, the head of Archeology Research Center of Iran's Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization announced that the oldest prehistorian village in the Middle East dating back to 9800 B.P., was discovered in Sahneh, located west of Kermanshah.[10][11]

Before Islam

In ancient Iranian mythology, construction of the city is attributed to Tahmoures Divband, the fabulous king of Pishdadian dynasty, however it is believed that the Sassanids have constructed Kermanshah. Bahram IV called Kermanshah gave his name to this city.[12] It was a glorious city in Sassanid period about the 4th century AD when it became the capital city and a significant health center serving as a summer resort for Sassanid kings. In AD 226, following a two-year war led by the Persian Emperor, Ardashir I, against Kurdish tribes in the region, the empire reinstated a local Kurdish prince, Kayus of Medya, to rule Kermanshah. Within the dynasty known as the House of Kayus (also Kâvusakân) remained a semi-independent Kurdish kingdom lasting until AD 380 before Ardashir II removed the dynasty's last ruling member.

After Islam

Kermanshah was conquered by the Arabs in AD 640. Under Seljuk rule in the eleventh century, it was a major cultural and commercial centre in Western Iran and the southern Kurdish region as a whole. The Safavids fortified the town, and the Qajars repulsed an attack by the Ottomans during Fath Ali Shah's rule (1797–1834). Kermanshah was occupied by Ottomans between 1723–1729 and 1731-1732.

Recent

Occupied by the Ottoman army in 1915 during World War I, it was evacuated in 1917. Kermanshah played an important role in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution during the Qajar period and the Republic Movement in Pahlavi period. The City was hit hard during the Iran–Iraq War, and although it was rebuilt, it has not yet fully recovered.

Naming dispute

After The Islamic Revolution in the late 1970s, the city was shortly named "Ghahramanshahr" and later the city and its province (called Kermanshahan before the revolution) were renamed Bakhtaran, apparently owing to the use of "Shah" in the original name. Bakhtaran means Western, which refers to the location of the city and the province within Iran. After the Iran–Iraq War, however, the city was renamed Kermanshah, as it resonates more with the desire of its people and the Persian and Kurdish literature and the collective memory of the Iranian people.

Climate

Kermanshah has a climate heavily influenced by the proximity of the Zagros mountains, classified as a Mediterranean climate (Csa) although much more continental than usually associated with that type. The city's altitude and exposed location relative to westerly winds makes precipitation a little bit high (more than twice that of Tehran), but at the same time produces huge diurnal temperature swings especially in the virtually rainless summers, which remain extremely hot during the day. Kermanshah experiences rather cold winters and there are usually rainfalls in fall and spring. Snow cover is seen for at least a couple of weeks during winter.

Climate data for Kermanshah, Iran Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Average high °C (°F) 6.5

(43.7)8.9

(48.0)14.3

(57.7)19.7

(67.5)25.8

(78.4)33.3

(91.9)37.8

(100.0)37.0

(98.6)32.5

(90.5)25.0

(77.0)16.7

(62.1)9.7

(49.5)22.3 Average low °C (°F) −4.3

(24.3)−3

(26.6)1.2

(34.2)5.1

(41.2)8.2

(46.8)11.4

(52.5)16.1

(61.0)15.4

(59.7)10.6

(51.1)6.4

(43.5)1.8

(35.2)1.7

(35.1)5.9 Precipitation mm (inches) 67.1

(2.642)62.9

(2.476)88.9

(3.5)69.9

(2.752)33.7

(1.327)0.5

(0.02)0.3

(0.012)0.3

(0.012)1.3

(0.051)29.2

(1.15)54.3

(2.138)70.3

(2.768)478.7

(18.846)Avg. precipitation days 9.4 9.1 10.4 8.7 5.6 0.2 0.1 0.2 0.3 3.6 6.0 8.1 61.7 Sunshine hours 133.3 152.5 179.8 204.0 266.6 348.0 350.3 337.9 306.0 241.8 189.0 148.8 2,858.0 Source: Hong Kong Observatory[13] Sightseeing

Kermanshah sights include Kohneh Bridge, Behistun Inscription, Taq-e Bostan, Temple of Anahita, Dinavar, Ganj Dareh, Essaqwand Rock Tombs, Sorkh Deh chamber tomb, Malek Tomb, Hulwan, Median dakhmeh (Darbad, Sahneh), Parav cave, Do-Ashkaft Cave, Tekyeh Moavenalmolk, Dokan Davood Inscription, Sar Pol-e-Zahab, Tagh e gara, Patagh pass, Sarab Niloufar, Ghoori Ghale Cave, Khaja Barookh's House, Chiyajani Tappe, Statue of Herakles in Behistun complex, Emad al doleh Mosque, Tekyeh-e Beglarbagi, Hunters cave, Jamé Mosque of Kermanshah, Godin Tepe, Bas relief of Gotarzes II of Parthia, and Anobanini bas relief.

Taq-e Bostan

Taq-e Bostan is a series of large rock relief from the era of Sassanid Empire of Persia, the Iranian dynasty which ruled western Asia from 226 to 650 AD. This example of Sassanid art is located 5 km from the city center of Kermanshah in western Iran. It is located in the heart of the Zagros mountains, where it has endured almost 1,700 years of wind and rain.

The carvings, some of the finest and best-preserved examples of Persian sculpture under the Sassanids, include representations of the investitures of Ardashir II (379–383) and Shapur III (383–388). Like other Sassanid symbols, Taq-e Bostan and its relief patterns accentuate power, religious tendencies, glory, honor, the vastness of the court, game and fighting spirit, festivity, joy, and rejoicing.

Sassanid kings chose a beautiful setting for their rock reliefs along an historic Silk Road caravan route waypoint and campground. The reliefs are adjacent a sacred spring that empties into a large reflecting pool at the base of a mountain cliff.

Taq-e Bostan and its rock relief are one of the 30 surviving Sassanid relics of the Zagros mountains. According to Arthur Pope, the founder of Iranian art and archeology Institute in the USA, "art was characteristic of the Iranian people and the gift which they endowed the world with."

One of the most impressive reliefs inside the largest grotto or ivan is the gigantic equestrian figure of the Sassanid king Khosrau II (591-628 AD) mounted on his favorite charger, Shabdiz. Both horse and rider are arrayed in full battle armor. The arch rests on two columns that bear delicately carved patterns showing the tree of life or the sacred tree. Above the arch and located on two opposite sides are figures of two winged angles with diadems. Around the outer layer of the arch, a conspicuous margin has been carved, jagged with flower patterns. These patterns are also found in the official costumes of Sassanid kings. Equestrian relief panel measured on 16.08.07 approx. 7.45 m across by 4.25 m high.

Behistun

Bisotun * UNESCO World Heritage Site

Country Iran (Islamic Republic of) Type Cultural Criteria ii, iii Reference 1222 Region ** Asia-Pacific Inscription history Inscription 521 BC (30th Session) * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List

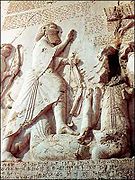

** Region as classified by UNESCOBehistun inscription is considered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Behistun Inscription (also Bisitun or Bisutun, Modern Persian: بیستون ; Old Persian: Bagastana, meaning "the god's place or land") is a multi-lingual inscription located on Mount Behistun.

The inscription includes three versions of the same text, written in three different cuneiform script languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. A British army officer, Henry Rawlinson, had the inscription transcribed in two parts, in 1835 and 1843. Rawlinson was able to translate the Old Persian cuneiform text in 1838, and the Elamite and Babylonian texts were translated by Rawlinson and others after 1843. Babylonian was a later form of Akkadian: both are Semitic languages. In effect, then, the inscription is to cuneiform what the Rosetta Stone is to Egyptian hieroglyphs: the document most crucial in the decipherment of a previously lost script.

The inscription is approximately 15 metres high by 25 metres wide, and 100 metres up a limestone cliff from an ancient road connecting the capitals of Babylonia and Media (Babylon and Ecbatana). It is extremely inaccessible as the mountainside was removed to make the inscription more visible after its completion. The Old Persian text contains 414 lines in five columns; the Elamite text includes 593 lines in eight columns and the Babylonian text is in 112 lines. The inscription was illustrated by a life-sized bas-relief of Darius, holding a bow as a sign of kingship, with his left foot on the chest of a figure lying on his back before him. The prostrate figure is reputed to be the pretender Gaumata. Darius is attended to the left by two servants, and ten one-metre figures stand to the right, with hands tied and rope around their necks, representing conquered peoples. Faravahar floats above, giving his blessing to the king. One figure appears to have been added after the others were completed, as was (oddly enough) Darius' beard,[citation needed] which is a separate block of stone attached with iron pins and lead.

Ghajar dynasty monuments

See also: Tekyeh Mo'avenalmolk and Khaja Barookh's HouseDuring the Qajar dynasty (1794 to 1925), Kermanshah Bazaar, Mosques and Tekyehs such as Moavenalmolk Mosque, and beautiful houses such as Khaja Barookh's House were built.

Tekyeh Moavenalmolk, is unique because it has many pictures on the walls that relate to shahnameh, despite some of its more religious ones.

Khaja Barookh's House is located in the old district of Faizabad, a Jewish neighborhood of Kermanshah. It was built by a Jewish merchant of the Qajar period, named Barookh. The house, an historical depiction of Iranian architecture, was renamed "Randeh-Kesh House", after the last owner, is a "daroongara"(pro-interior)house and is connected through a vestibule to the exterior yard and through a corridor to the interior yard.[3] Surrounding the interior yard are rooms, brick pillars making the iwans(porches) of the house, and step-like column capitals decorated with brick-stalactite work. This house is among the rare Qajar houses with a private bathroom.

Museums

There are four museums that are established in old houses of Qajar period. These are Museum of ethnography at Tekyeh Moavenalmolk, and two museums of Zagros Paleolithic Museum and Museum of epigraphy and Qajar hand writings at Tekieh Biglar Baigi. The Zagros Paleolithic Museum contains rich collections of stone tools and animal fossil bones from various Paleolithic sites in Iran. It is the first established museum in Iran that devoted to Paleolithic period of Iran. Museum of traditional Martial art (Wrestling موزه پهلوانی) is another museum in Kermanshah that was established recently and contains many wax models of traditional wrestlers.

Economy

Kermanshah is one of the western agricultural core of Iran that produces grain, rice, vegetable, fruits, and oilseeds, however Kermanshah is emerging as a fairly important industrial city; there are two industrial centers with more than 256 manufacturing units in the suburb of the city. These industries include petrochemical refinery, textile manufacturing, food processing, carpet making, sugar refining, and the production of electrical equipment and tools. Kermanshah Oil Refining Company (KORC) established in 1932 by British companies, is one of the major industries in the city. After recent changes in Iraq, Kermanshah has become one of the main importing and exporting gates of Iran.

Higher education

- Kermanshah University of Technology

- Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences

- Razi University

- Islamic Azad University, Kermanshah Branch

- Payame Noor University

Notable people

- Doris Lessing, writer, 2007 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (born in Kermanshah to British parents)

- André Molitor, former clerk of the great Belgian State and former chief of staff of the King Baudouin I of Belgium, professor of public administration at the Catholic University of Leuven (Louvain).

- Shahram Nazeri, vocalist and musician

- Kayhan Kalhor, musician

- Pouran Derakhshandeh, film director, producer, screen writer

- Reza Shafiei Jam, actor

- Karim Sanjabi, Iran's attorney in the oil's national movement, former foreign minister

- Massoud Azarnoush, archaeologist

- Rashid Yasemi, one of the Five-Masters of Persian Literature

- Moeini kermanshahi, songwriter

- Ali Mohammad Afghani, novelist

- Ali Ashraf Darvishian, novelist and writer

- Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor, famous calligrapher

- Abolghasem Lahouti, poet

- Sousan (Golandam Taherkhani), singer

- Nozar Azadi, actor

- Reza Fieze Norouzi, actor

- Alexis Kouros, writer, documentary-maker, director and producer

- Roknoddin Mokhtari, violin player

- Nasser Zarafshan, novelist, translator, and attorney

- Bijan Namdar Zangeneh, former minister

- Mohammad Mokri, politician, kurdologist, writer, poet, linguist, researcher

- Ebrahim Azizi, member and spokesman of the Guardian Council

- Mir Jalaleddin Kazzazi, writer

- Al-Dinawari, botanist, historian, geographer, astronomer and mathematician

- Shahram Amiri, nuclear scientist

- Hajj Nematollah, mystic

- Javad Sharifi, poet

- Mohammad Ranjbar, former Iran national football team player and coach

- Mohammad Hassan Mohebbi, light heavyweight freestyle wrestler & Iran's national team coach

- Kourosh Bagheri, World weightlifting champion

- Ali Mazaheri, 2006 Asian Games gold medalist, Asian champion & Olympic boxer

- Homa Hosseini, rower

- Ali Akbar Moradi, Musician and Tanbour Player

- Hayedeh (Ma'soumeh Dadehbala), singer

- Mahasti (Eftekhar Dadehbala), singer

- Guity Novin, painter & graphic designer

- Sohrab Pournazeri, musician

- Mahshid Amirshahi, writer

- Kianoush Rostami, world weight lifting champion

Photos of Kermanshah

Taq-e Bostan Lake Carving of Khosrow Parviz[fn 1] Ferdowsi Square Anahita Temple in Kangavar Mount Dalekhani Ghouri Ghaleh Cave Ghouri Ghaleh Cave Bisotun Inscription[fn 2] Close-Up of Bisotun Inscription Taq-e Bostan Carving [fn 4] Tekye moaven ol molk Mount Parau Foot Notes

- ^ Khosrow Parviz is standing here. On his left is Ahura Mazda, on his right is Anahita, and below is, Khosrau dressed as a mounted Persian knight riding on his favourite horse, Shabdiz.

- ^ Authored by Darius the Great sometime between his coronation as king of the Persian Empire in the summer of 522 BC and his death in autumn of 486 BC.

- ^ Women playing harp while the king is standing in a boat holding his bow and arrows, from 6th century Sassanid Iran.

- ^ Female musicians accompanying king during hunting. These are identified as unfinished carvings, the figures have been blocked-out but yet to be completed [compare with figure bottom right foreground], as elsewhere on the two hunting panels in the larger iwan.

Sister Cities

See also

- Kermanshah Province

- Kermanshahi

- Kalhor

- Warwasi cave

- Visual Art High school of Kermanshah

External links

- Pictures of Inscription and Bas relief of Darius the Great - Free Pictures of IRAN irantooth.com

- Photos from Bisotun Complex - From Online Photo Gallery Of Aryo.ir

- Photos from Taq-e Bostan - From Online Photo Gallery Of Aryo.ir

- Photos from Moavenol Molk Tekieh - From Online Photo Gallery Of Aryo.ir

References

- ^ Kermanshah can be found at GEOnet Names Server, at this link, by opening the Advanced Search box, entering "-3070245" in the "Unique Feature Id" form, and clicking on "Search Database".

- ^ "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006)" (Excel). Islamic Republic of Iran. http://www.amar.org.ir/DesktopModules/FTPManager/upload/upload2360/newjkh/newjkh/05.xls.

- ^ http://www.assistnews.net/Stories/2010/s10020115.htm

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Iran Chamber society: accessed: September 2010.

- ^ روزنامه سلام کرمانشاه Persian (Kurdish)

- ^ آشنایی با فرهنگ و نژاد استان کرمانشاه(Persian)

- ^ سازمان میراث فرهنگی، صنایع دستی و گردشگری استان کرمانشاه بازدید 2010/03/11

- ^ "Most ancient Mid East village discovered in western Iran". 2009. http://www.isna.ir/ISNA/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-1344672&Lang=E. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ^ "با 11800 سال قدمت، قديميترين روستاي خاورميانه در كرمانشاه كشف شد". 2009. http://kermanshah.isna.ir/mainnews.php?ID=News-22054. Retrieved 2009-05-23.[dead link]

- ^ Dehkhoda: Kermanshah.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Kermanshah, Iran". HKO. 2007. http://www.hko.gov.hk/wxinfo/climat/world/eng/asia/westasia/kermanshah_e.htm. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

Kermanshah Province

Kermanshah ProvinceCapital Kermanshah

Counties and Cities Kerend-e Gharb · GahvarehEslamabad-e Gharb CountyEslamabad-e Gharb · HomeylGilan-e Gharb CountyGilan-e Gharb · SarmastQasr-e Shirin CountyRavansar CountySalas-e Babajani CountySarpol-e Zahab CountySights Kohneh Bridge · Behistun Inscription · Taq-e Bostan · Temple of Anahita · Dinavar · Ganj Dareh · Essaqwand Rock Tombs · Sorkh Deh chamber tomb · Malek Tomb · Hulwan · Median dakhmeh(Darbad,Sahneh) · Parav cave · Do-Ashkaft Cave · Tekyeh-e Moavenalmolk · Dokan Davood Inscription,Sar Pol-e-Zahab · Tagh e gara,Patagh pass · Sarab Niloufar · Ghoori Ghale Cave · Khaja Barookh's House · Chiyajani Tappe · Statue of Herakles in Behistun complex · Emad al doleh Mosque · Tekyeh-e Beglarbagi · Hunters cave,Behistun_complex · Jamé Mosque of Kermanshah · Godin Tepe · Bas relief of Gotarzes II of Parthia · Anobanini bas relief,Sarpol-e-Zahab ·Categories:- Kermanshah County

- Cities in Iran

- Cities in Kermanshah Province

- Iranian provincial capitals

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.