- Dry ice

-

Dry ice, sometimes referred to as "Cardice" or as "card ice", is the solid form of carbon dioxide. It is used primarily as a cooling agent. Its advantages include lower temperature than that of water ice and not leaving any residue (other than incidental frost from moisture in the atmosphere). It is useful for preserving frozen foods, ice cream, etc., where mechanical cooling is unavailable.

The extreme cold makes the solid dangerous to handle without protection due to burns caused by freezing (frostbite). While generally nontoxic, the outgassing from it can cause suffocation due to displacement of oxygen in confined locations.

Contents

Properties

Dry ice is the solid form of carbon dioxide (chemical formula CO2), comprising two oxygen atoms bonded to a single carbon atom. It is colorless, odorless, non-flammable, and slightly acidic.[1]

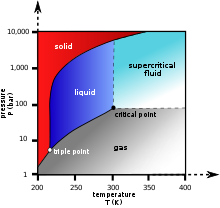

At temperatures below −56.4 °C (−69.5 °F) and pressures below 5.13 atm (the triple point), CO2 changes from a solid to a gas with no intervening liquid form, through a process called sublimation. The opposite process is called deposition, where CO2 changes from the gas to solid phase (dry ice). At atmospheric pressure, sublimation/deposition occurs at −78.5 °C (−109.3 °F).

The density of dry ice varies, but usually ranges between about 1.4 and 1.6 g/cm3 (87–100 lb/ft3).[2] The low temperature and direct sublimation to a gas makes dry ice an effective coolant, since it is colder than water ice and leaves no residue as it changes state.[3] Its enthalpy of sublimation is 571 kJ/kg (25.2 kJ/mol).

Dry ice is non-polar, with a dipole moment of zero, so attractive intermolecular van der Waals forces operate.[4] The composition results in low thermal and electrical conductivity.[5]

History

It is generally accepted that dry ice was first observed in 1834 by French chemist Charles Thilorier, who published the first account of the substance.[6][7] In his experiments, he noted that when opening the lid of a large cylinder containing liquid carbon dioxide, most of the liquid CO2 quickly evaporated. This left only solid dry ice in the container.[6] In 1924, Thomas B. Slate applied for a US patent to sell dry ice commercially. Subsequently, he became the first to make dry ice successful as an industry.[8] In 1925, this solid form of CO2 was trademarked by the DryIce Corporation of America as "Dry ice", thus leading to its common name.[9] That same year the DryIce Co. sold the substance commercially for the first time; marketing it for refrigerating purposes.[8]

The alternative name "Cardice" is a registered trademark of Air Liquide UK Ltd.[10] It is sometimes written as "card ice".[11]

Manufacture

Dry ice is easily manufactured.[12][13] First, gases with a high concentration of carbon dioxide are produced. Such gases can be a byproduct of another process, such as producing ammonia from nitrogen and natural gas, or large-scale fermentation.[13] Second, the carbon dioxide-rich gas is pressurized and refrigerated until it liquifies. Next, the pressure is reduced. When this occurs some liquid carbon dioxide vaporizes, causing a rapid lowering of temperature of the remaining liquid. As a result, the extreme cold causes the liquid to solidify into a snow-like consistency. Finally, the snow-like solid carbon dioxide is compressed into either small pellets or larger blocks of dry ice.[14][15]

Dry ice is typically produced in two standard forms: blocks and cylindrical pellets. A standard block weighing approximately 30 kg is most common. These are commonly used in shipping, because they sublimate relative slowly due to a low ratio of surface area to volume. Pellets are around 1 cm (0.4 in) in diameter and can be bagged easily. This form is suited to small scale use, for example at grocery stores and laboratories.[citation needed]

Applications

Commercial

The most common use of dry ice is to preserve food,[1] using non-cyclic refrigeration.

It is frequently used to package items that need to remain cold or frozen, such as ice cream or biological samples, without the use of mechanical cooling.[citation needed]

Dry ice can be used to flash freeze food,[16] laboratory biological samples,[17] carbonate beverages,[16] and make ice cream.[18]

Dry ice can be used to arrest and prevent insect activity in closed containers of grains and grain products, as it displaces oxygen, but does not alter the taste or quality of such foods. For the same reason, it can prevent or retard food oils and fats from becoming rancid.

When dry ice is placed in water sublimation is accelerated, and low-sinking, dense clouds of smoke-like fog are created. This is used in fog machines, at theaters, discothèques, haunted house attractions, and nightclubs for dramatic effects. Unlike most artificial fog machines, in which fog rises like smoke, fog from dry ice hovers above the ground.[15] Dry ice is useful in theater productions that require dense fog effects.[19]

It is occasionally used to freeze and remove warts.[20] However, liquid nitrogen performs better in this role, since it is colder so requires less time to act and less pressure.[21] However, dry ice has the advantage of having fewer problems with storage, since it can be generated from compressed carbon dioxide gas as needed.[21]

Plumbers use equipment that forces pressurised liquid CO2 into a jacket around a pipe; the dry ice formed causes the water to freeze, forming an ice plug, allowing them to perform repairs without turning off the water mains. This technique can be used on pipes up to 4 inches (100 mm) in diameter.[22]

Dry ice can be used as bait to trap mosquitoes, bedbugs, and other insects, due to their attraction to carbon dioxide.[23]

Industrial

Dry ice can be used for loosening asphalt floor tiles or car sound deadening making it easy to pry off,[24] as well as freezing water in valveless pipes to enable repair.[25]

One of the largest mechanical uses of dry ice is blast cleaning. Dry ice pellets are shot out of a nozzle with compressed air, combining the power of the speed of the pellets with the action of the sublimation. This can remove residues from industrial equipment. Examples of materials being removed include ink, glue, oil, paint, mold and rubber. Dry ice blasting can replace sandblasting, steam blasting, water blasting or solvent blasting. The primary environmental residue of dry ice blasting is the sublimed CO2, thus making it a useful technique where residues from other blasting techniques are undesirable.[26][dead link] Recently, blast cleaning has been introduced into the industry of removing smoke damage from structures after fires.

Dry ice is also useful for the de-gassing of flammable vapours from storage tanks — the sublimation of dry ice pellets inside an emptied and vented tank causes an outrush of CO2 that carries with it the flammable vapours.[27]

The removal and fitting of cylinder liners in large marine engines requires the use of dry ice to chill and thus shrink the liner so that it freely slides within the block. When warmed in place the resulting interference fit prevents motion. Similar procedures may be used in fabricating mechanical assemblies with a high resultant strength, replacing the need for pins, keys or welds.[28]

It is also useful as a cutting fluid.

Scientific

In laboratories, a slurry of dry ice in an organic solvent is a useful freezing mixture for cold chemical reactions and for condensing solvents in rotary evaporators.[29]

The process of altering cloud precipitation can be done with the use of dry ice.[30] It was widely used in experiments in the US in the 1950s and early 60s before being replaced by silver iodide.[30] Dry ice has the advantage of being relatively cheap and completely non-toxic.[30] Its main drawback is the need to be delivered directly into the supercooled region of clouds being seeded.[30]

Dry ice bombs

Dry ice is an ingredient in dry ice bombs. A dry ice bomb is a bomb-like device using dry ice and water-filled container, such as a plastic bottle. As the dry ice sublimates, pressure increases, usually causing the bottle to explode.

California law defines "destructive device" as a type of weapon, including "any sealed device containing dry ice (CO2) or other chemically-reactive substances assembled for the purpose of causing an explosion by a chemical reaction."[31] However, dry ice bombs operate not via chemical reaction but via a phase change. The approximate volume of carbon dioxide gas produced by sublimating a known mass of dry ice can be calculated using the Ideal gas law.

The bomb was featured on MythBusters, episode 57 Mentos and Soda, which first aired on August 9, 2006.[32] It was also featured in an episode of Time Warp.

Safety

Prolonged exposure to dry ice can cause severe skin damage through frostbites, and the fog produced may also hinder attempts to withdraw from contact in a safe manner. Because it sublimates into large quantities of carbon dioxide gas, which could displace oxygen-containing air and pose a danger of asphyxiation, dry ice should only be exposed to open air in a well-ventilated environment.[24] For this reason, dry ice is assigned the S-phrase S9 in the context of laboratory safety. Industrial dry ice may contain contaminants that make it unsafe for direct contact with foodstuffs.[33]

Although dry ice is not classified as a dangerous substance by the European Union,[34] or as a hazardous material by the DOT for ground transportation, when shipped by air or water, it is regulated as a dangerous good and IATA packing instruction 904 (IATA PI 904) requires that it be labeled specially, including a diamond-shaped black-and white label, UN 1845. Also, arrangements must be in place to ensure adequate ventilation so that pressure build-up does not rupture the packaging.[35] The Federal Aviation Administration in the US allows airline passengers to carry up to 2 kg of dry ice in carry-on baggage and 2.3 kg in checked baggage, when used to refrigerate perishables.[36]

Occurrence on Mars

Following the Mars flyby of the Mariner 4 spacecraft in 1966, scientists concluded that Mars' polar caps consist entirely of dry ice.[37] However, findings made in 2003 by researchers at the California Institute of Technology have shown that Mars' polar caps are almost completely made of water ice, and that dry ice only forms a thin surface layer that thickens and thins seasonally.[37][38] A phenomenon named dry ice storms was proposed to occur over the polar regions of Mars. They are comparable to Earth's thunderstorms, with crystalline CO2 taking the place of water in the clouds.[39]

References

- ^ a b Yaws 2001, p. 125

- ^ Häring 2008, p. 200

- ^ Yaws 2001, p. 124

- ^ Khanna & Kapila 2008, p. 161

- ^ Khanna & Kapila 2008, p. 163

- ^ a b Duane 1952

- ^ Charles Thilorier; Thilorier, M. (1834). "Solidification de l'Acide carbonique" (in French). Comptes rendus 1 (2): 194. doi:10.1086/349402. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k29606/f194.table.

- ^ a b Killeffer, D.H. (October 1930). "The Growing Industry-Dry-Ice". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry (Industrial & Engineering Chemistry) 22 (10): 1087. doi:10.1021/ie50250a022.

- ^ The Trade-mark Reporter. United States Trademark Association. 1930. ISBN 1598880918.

- ^ "Case details for Trade Mark 516211". UK Intellectual Property Office. http://www.ipo.gov.uk/domestic?domesticnum=516211. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Treloar 2003, p. 175

- ^ "What is Dry Ice?". Continental Carbonic Products, Inc.. http://www.continentalcarbonic.com/dryice/. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ a b "Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Properties, Uses, Applications: CO2 Gas and Liquid Carbon Dioxide". Universal Industrial Gases, Inc.. http://www.uigi.com/carbondioxide.html. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Good plant design and operation for onshore carbon capture installations and onshore pipelines. The Energy Institute. London. September 2010. p. 10

- ^ a b "How does dry ice work?". HowStuffWorks. http://www.howstuffworks.com/question264.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ a b "Cool Uses for Dry Ice". Airgas.com. http://www.airgas.com/content/details.aspx?id=7000000000103. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Preparing Competent E. coli with RF1/RF2 solutions". Personal.psu.edu. http://www.personal.psu.edu/dsg11/labmanual/DNA_manipulations/Comp_bact_by_RF1_RF2.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Blumenthal, Heston (2006-10-29). "How to make the best treacle tart and ice cream in the world". London: The Sunday Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/food_and_drink/heston_blumenthal/article607734.ece?print=yes. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ McCarthy 1992

- ^ Lyell A. (1966). "Management of warts". British medical journal 2 (5529): 1576–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5529.1576. PMC 1944935. PMID 5926267. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1944935.

- ^ a b Goroll & Mulley 2009, p. 1317

- ^ Treloar 2003, p. 528

- ^ Reisen WK, Boyce K, Cummings RC, Delgado O, Gutierrez A, Meyer RP, Scott TW. (1999). "Comparative effectiveness of three adult mosquito sampling methods in habitats representative of four different biomes of California". J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 15 (1): 24–31. PMID 10342265.

- ^ a b Magazines, Hearst (February 1961). "Dry ice pops off Asphalt Tile". Popular Mechanics 115 (2): 169. http://books.google.com/books?id=R9wDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA169.

- ^ Corporation, Bonnier (July 1960). "Dry Ice as a Plumbing Aid". Popular Science 177 (1): 159. http://books.google.com/books?id=VCYDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA159.

- ^ Wolcott, John (January, 2008). "Ice-blasting firm offers a cool way to clean up". The Daily Herald. http://www.heraldbusinessjournal.com/archive/jan08/iceblasting-jan08.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ Dry ice

- ^ Bushing and Plain Bearings Press or Shrink Fit Design and Application

- ^ Housecroft 2001, p. 410

- ^ a b c d Keyes 2006, p. 83

- ^ "CA Codes (pen:12301-12316)". http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-bin/displaycode?section=pen&group=12001-13000&file=12301-12316.

- ^ "Mythbusters episode 57". http://mythbustersresults.com/episode57.

- ^ Nelson, Lewis (2000). "Carbon Dioxide Poisoning". Emergency Medicine. http://www.emedmag.com/html/pre/tox/0500.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament". http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32008R1272:EN:NOT. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- ^ Requirements for Shipping Dry Ice (IATA PI 904). Environmental Resource Center. 24 May 2006. http://www.ercweb.com/resources/viewreg.aspx?id=6779. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- ^ "Hazardous Materials Information for Passengers". http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ash/ash_programs/hazmat/media/MaterialsCarriedByPassengersAndCrew.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-26. available on the FAA website: http://www.faa.gov/

- ^ a b Mars Poles Covered by Water Ice, Research Shows. National Geographic. 13 February 2003. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/02/0213_030213_marspoles.html. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Byrne, S.; Ingersoll, AP (2003-02-14). "A Sublimation Model for Martian South Polar Ice Features". Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 299 (5609): 1051–3. Bibcode 2003Sci...299.1051B. doi:10.1126/science.1080148. PMID 12586939. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/short/299/5609/1051. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ Dry Ice Storms May Pelt Martian Poles, Experts Say. National Geographic. 19 December 2005. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/12/1219_051219_mars_ice.html. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

Bibliography

- Yaws, Carl (2001). Matheson gas data book (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 982. ISBN 9780071358545. http://books.google.com/?id=Sfvbgvu9OQMC. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- Häring, Heinz-Wolfgang (2008). Industrial Gases Processing. Christine Ahner. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 9783527316854. http://books.google.com/?id=93SPB4v1Lk8C. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- Treloar, Roy (2003). Plumbing Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405106139. http://books.google.com/?id=CEyW2EkaogEC&pg=PA175. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- Housecroft, Catherine; Sharpe, Alan G (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Harlow: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0582310806. http://books.google.com/?id=3sy4ZAP4EGAC&pg=PA410. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- Mitra, Somenath (2003). Sample preparation techniques in analytical chemistry. Wiley-IEEE. ISBN 9780471328452. http://books.google.com/?id=yk1RZ9HD6hcC. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- McCarthy, Robert E. (1992). Secrets of Hollywood special effects. Boston: Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80108-3. http://books.google.com/?id=B4applRToVQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=isbn:0240801083#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Duane, H. D. Roller; Thilorier, M. (1952). "Thilyorier and the First Solidification of a "Permanent" Gas (1835)". Isis 43 (2): 109–113. doi:10.1086/349402. JSTOR 227174.

- Khanna, S. K.; Kapila, Dr. B. (2008). Comprehensive Chemistry X. Laxmi Publications. ISBN 9788170085966. http://books.google.com/?id=qQQcOhxHdxoC&pg=PA161&dq=%22dry+ice%22+%22non-polar%22. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- Goroll, Allan H; Mulley, Albert G (2009). Primary Care Medicine: Office Evaluation and Management of the Adult Patient. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781775137.

- Keyes, Conrad G (2006). Guidelines for cloud seeding to augment precipitation. American Society of Civil Engineers. ASCE Publications. ISBN 9780784408193.

External links

Categories:- Carbon dioxide

- Coolants

- Refrigerants

- Ice

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.