- Chaco War

-

Chaco War, Interwar Period

Bolivia and Paraguay before the 1932 WarDate 15 June 1932 – 12 June 1935 Location Gran Chaco region, South America Result Paraguayan victory Territorial

changesMost of the Gran Chaco region awarded to Paraguay Belligerents  Bolivia

Bolivia Paraguay

ParaguayCommanders and leaders Daniel Salamanca Urey

General Hans Kundt

General Enrique PeñarandaEusebio Ayala

Marshal José Félix EstigarribiaStrength 250,000 150,000 Casualties and losses 57,000 casualties 43,000 casualties The Chaco War (1932–1935) was fought between Bolivia and Paraguay over control of the northern part of the Gran Chaco region (known as Chaco Boreal) of South America, which was incorrectly thought to be rich in oil. It is also referred to as La Guerra de la Sed (Spanish for "War of Thirst") in literary circles for being fought in the semi-arid Chaco. It was the bloodiest military conflict fought in South America during the 20th century. The war pitted two of South America's poorest countries, both having previously lost territories to neighbors in wars during the 19th century. During the war both countries faced difficulties in obtaining arms and other supplies since their landlocked situation made their foreign trade and arms purchases dependent on the willingness of neighboring countries to let them pass by. In particular Bolivia faced external trade problems coupled with poor internal communications. While Bolivia had income from lucrative mining and a better equipped and larger army than Paraguay, a series of factors turned the tide in favour of Paraguay which came by the end of the war to control most of the disputed zone, and was finally also granted two-thirds of the disputed territories in the peace treaties.

Contents

Origins

Though the region was sparsely populated, control of the Paraguay River running through it would have given one of the two landlocked countries access to the Atlantic Ocean. This was especially important to Bolivia, which had lost its Pacific Ocean coast to Chile in the War of the Pacific (1883).

In international arbitration, Bolivia argued that the region had been part of the original Spanish colonial province of Moxos and Chiquitos to which Bolivia was heir. Meanwhile, Paraguay based its case on the occupation of the land. Indeed, both Paraguayan and Argentine planters were already breeding cattle and exploiting quebracho woods in the area,[1] while the small nomadic indigenous population of Guaraní-speaking tribes was related to that country's own Guaraní heritage. As of 1919, Argentine banks owned 400,000 hectares of land in the eastern Chaco, while the Casado family, a powerful member of the Argentine oligarchy, held 141,000.[2] The presence of Mennonite colonies in the Chaco, who settled there under the auspices of the Paraguayan Parliament, was another factor in favour of Paraguay's claim.[3]

Furthermore, the discovery of oil in the Andean foothills sparked speculation that the Chaco itself might be a rich source of petroleum. Foreign oil companies were involved in the exploration: companies mainly descended from Standard Oil backed Bolivia, while Shell Oil supported Paraguay. Standard was already producing oil from wells in the high hills of eastern Bolivia, around Villa Montes.

Paraguay had lost almost half of its territory to Brazil and Argentina in the War of the Triple Alliance and was not prepared to see what it was perceived as its last chance for a viable economy fall victim to Bolivia.[4] Border skirmishes since 1927 culminated in an all-out war in 1932.

Prelude to the war

The first confrontation between the two countries dates back to 1885, when the Bolivian entrepreneur Miguel Araña Suarez founded Puerto Pacheco, a port on the upper Paraguay river, south of Bahía Negra. He assumed that the new settlement was well inside Bolivian territory, but Bahía Negra had been implicitly recognized as Paraguayan by Bolivia. The Paraguayan government sent in a naval detachment aboard the gunboat Pirapó, which forcibly evicted the Bolivians from the area in 1888.[5][6] The incident was followed by two agreements -in 1894 and 1907- which were never approved by either the Bolivian or the Paraguayan parliament.[7] Meanwhile, in 1905, Bolivia founded two new outposts in the Chaco, Ballivián and Guachalla, this time along the Pilcomayo River. The Bolivian government ignored the half-hearted Paraguayan official protest.[6]

Bolivian penetration in the region went unopposed until 1927, when the first blood was shed over the Chaco Boreal. On 27 February, a Paraguayan army patrol and its native guides were taken prisoners near the Pilcomayo river and held in the Bolivian outpost of Fortin Sorpresa, where the commander of the Paraguayan platoon, Lieutenant Adolfo Rojas Silva, was shot and killed in suspicious circumstances. Fortín (Spanish for "little fort") was the name used for the small pillbox and trench-like garrisons in the Chaco, although the troops barracks usually were no more than a few mud huts. While the Bolivian government formally regretted the death of Rojas Silva, the Paraguayan public opinion called it "murder".[2] After the subsequent talks arranged in Buenos Aires failed to produce any agreement and eventually collapsed in January 1928, the dispute grew violent. On 5 December 1928 Fortin Vanguardia, an advanced outpost established by the Bolivian army a few miles northwest of Bahía Negra, was overrun by a cavalry party, which captured 21 Bolivian soldiers and burnt the scattered huts to the ground.[8] The Bolivians retaliated with an air strike on Bahía Negra on 15 December, which didn't cause too much casualties or damage. On 14 December, Fortin Boquerón, which later would be the site of the first major battle of the campaign, was seized by Bolivia at the cost of 15 Paraguayan lives. A return to the status quo ante was eventually agreed on 12 September 1929 in Washington, under the pressure of the Pan American League, but an arms race had already begun and both countries were on a course of collision with one another.[9]

Composition of the armies

Paraguay had a population only a third as large as that of Bolivia (880,000 versus 2,150,000), but its guerrilla style of fighting, compared to Bolivia's more conventional strategy, enabled Paraguay to take the upper hand. In June 1932, the Paraguayan army totaled about 4,026 men (355 combat officers, 146 surgeons and non-combatant officers, 200 cadets, 690 NCOs, and 2,653 soldiers). Both racially and culturally, the Paraguayan army was practically homogeneous. Almost all of the soldiers were European-Guarani mestizos. In Bolivia, however, most of the soldiers were Altiplano Native Americans of Quechua or Aymará descent (90% of the infantry troops), the lower-ranking officers were of Spanish or other European ancestry, and General Hans Kundt was German. In spite of the fact that the Bolivian army had more manpower, the Bolivian army never mobilized more than 60,000 soldiers, and never more than two-thirds of the army were on the Chaco at one time, while Paraguay mobilized its entire army.[10] City buses were confiscated, wedding rings were donated to buy weapons, by 1935 Paraguay had widened conscription to include 17 year-olds and policemen. While both armies deployed a good number of cavalry regiments, these were actually infantry troops, since it was soon learned that the Chaco can't provide enough water and forage for the horses. Only a number of squadrons carried out reconnaissance missions at divisional level.[11] In the course of the conflict, the Paraguayan factories developed their own type of hand grenade, the carumbe'i (Guaraní for "little turtle")[12][13] and produced trailers, artillery grenades and aerial bombs. The Paraguayan war effort was centralized and led by the state-owned national dockyards, managed by captain José Bozzano.[14][15] The Paraguayan army received the first consignment of carumbe'i grenades in January 1933.[12]

The Paraguayans took advantage of their ability to communicate over the radio in Guaraní, which was not intelligible to the average Bolivian soldier. Paraguay had little trouble in mobilizing its troops in large barges on the Paraguay river right to the frontlines, whilst the majority of Bolivian soldiers came from the western highlands, some eight hundred kilometers away and with little or no logistic support. In fact, it took a Bolivian soldier about 14 days to traverse the distance, while a Paraguayan soldier only took about four.[10] The heavy equipment of Bolivia's army made things worse. The supply of water, given the dry climate of the region, also played a key role during the conflict. There were thousands of non-combat casualties due to dehydration, mostly among Bolivian troops.

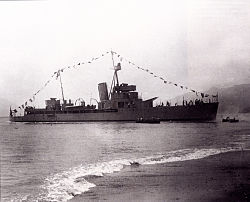

See also: Aerial operations in the Chaco War One of the key Paraguayan assets, the gunboat Humaitá shortly after being laid down in Italy, without her main armament

One of the key Paraguayan assets, the gunboat Humaitá shortly after being laid down in Italy, without her main armament

The Chaco War is also important historically as the first instance of large scale aerial warfare to take place in the Americas. Both sides used obsolete single-engined biplane fighter-bombers; the Paraguayans deployed 14 Potez 25, while the Bolivians made extensive use of at least 20 CW-14 Osprey. Despite an international arms embargo imposed by the League of Nations, Bolivia in particular went to great lengths in trying to import a small number of Curtiss T-32 Condor II twin-engined bombers masqueraded as civil transports, only to be halted in Peru during deliveries.[16] At Ballivián, the last ever dogfight between bi-planes took place.[17]

The Paraguayan navy played a key role in carrying thousand of troops and supplies to the frontlines through the Paraguay River, as well as in providing antiaircraft support to transport ships and port facilities.[18] Two Italian-built gunboats, the Humaitá and Paraguay ferried troops to Puerto Casado. On 22 December 1932, three Bolivian Vickers Vespa attacked the riverine outpost of Bahía Negra, killing a Paraguayan army colonel, but losing one of the aircraft, shot down by the gunboat Tacuary. The two surviving Vespas met another gunboat, the Humaitá, while flying downriver. Paraguayan sources claim that one of them was damaged.[19][20] Conversely, the Bolivian army reported that the Humaitá limped back to Asunción seriously damaged.[21] Shortly before 29 March 1933 a Bolivian Osprey was shot down over the Paraguay river,[22] while on 27 April, a strike package of six Ospreys launched a successful mission from their base at Muñoz against the logistic riverine base and town of Puerto Casado, although the strong reaction of Argentine diplomacy prevented any further strategic attacks on targets along the Paraguay river.[23] On 26 November 1934, the Brazilian steamer Paraguay was strafed and bombed by mistake by Bolivian aircraft while sailing the Paraguay river near Puerto Mihanovich. The Brazilian government sent 11 naval planes to the area, and its navy begun to convoy shipping on the river.[24][25][26]

The Paraguayan navy air service was also very active in the conflict, harassing Bolivian troops deployed along the northern front with flying boats. The aircraft were moored at Bahía Negra Naval Air Base, and consisted of two Macchi M.18.[27] These seaplanes carried out the first night air attack in South America when they raided the Bolivian outposts of Vitriones and San Juan,[28] on 22 December 1934. Every year since then, the Paraguayan navy celebrates the 'day of the Naval Air Service' on the anniversary of the action.[29]

The Bolivian army deployed at least ten locally-built patrol boats and transport vessels during the conflict,[30] mostly to ship military supplies to the northern Chaco through the Mamoré-Madeira system.[31] The transport ships Presidente Saavedra and Presidente Siles steamed on the Paraguay river from 1927 until the beginning of the war, when both units were sold to private companies.[30] The 50-ton armed launch Tahuamanu based in the Mamoré-Madeira system was briefly transferred to Laguna Cáceres to ferry troops downriver from Puerto Suárez, challenging for eight months the Paraguayan naval presence in Bahía Negra. She was withdrawn to the Itenez river in northern Bolivia after the Bolivian aerial reconnaissance revealed the actual strength of the Paraguayan navy in the area.[30][32]

Conflict

Pitiantutá Lake Incident

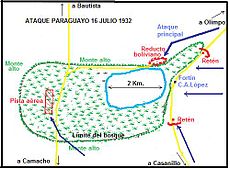

On June 15 of 1932 a Bolivian detachment captured and burned to the ground the Fortín Carlos Antonio López at Pitiantutá Lake disobeying explicit orders by Bolivian President Daniel Salamanca to avoid provocations in the Chaco region. One month later, on July 16, a Paraguayan detachment evicted the Bolivian troops from the area. The lake was located at 21°19′38″S 59°44′12″W / 21.32722°S 59.73667°W and had been discovered by Paraguayan explorers in March 1931, but the Bolivian High Command was unaware of this when one of their aircraft spotted the body of water on April 1932. After the initial incident Salamaca then changed his status quo policy over the disputed area and ordered the outposts of Corrales, Toledo and Boquerón to be captured. The three were soon taken over and in response Paraguay called for a Bolivian withdrawal. Salamanca instead demanded them to be included in a "zone of dispute". On a memorandum directed to President Salamanca on August 30 Bolivian general Filiberto Osorio expressed his concerns over the lack of a plan of operations and attached a plan of operations focusing on a offensive from the north. At the same time Bolivian General Quintanilla asked for permission to capture two additional Paraguayan garrisons; Nanawa and Rojas Silva. During August Bolivia slowly reinforced its 4,000 men strong First Bolivian Army located in the zone of conflict with 6,000 men.

The breaking of the fragile status quo in the disputed areas of the Chaco by Bolivians convinced Paraguay that a diplomatic solution on agreeable terms was not possible. Paraguay gave its army general staff orders to recapture the three forts. During the month of August, Paraguay mobilized over ten thousand men into the Chaco region. Paraguayan general José Félix Estigarribia prepared for a large offensive before the Bolivians would have mobilized their whole army.

First Paraguayan Offensive

Further information: Battle of BoquerónFortín Boquerón was the first target of Paraguayan Offensive. The Boquerón complex, guarded by 619 Bolivians resisted a 22-day siege against 5,000 Paraguayan troops. An additional 2,500 Bolivians attempted to relieve the siege from the southwest but were fought back by 2,200 Paraguayans that defended the accesses to the siege area. A few Bolivian units managed to enter Fortín Boquerón with supplies and the Bolivian Air Force dropped food and ammunition to the besieged soldiers. Having begun on 7 September, the siege ended when Fortín Boquerón finally fell on 29 September 1932.

After the fall of Fortín Boquerón, the Paraguayans continued their offensive and made a pincer movement, which forced fractions of the Bolivian army to surrender. While the Paraguayans had expected to set a new siege on Fortín Arce, the most advanced Bolivian outpost in the Chaco, they found it in ruins. The 4,000 Bolivians that defended Arce had been moved to Fortín Alihuatá.

Bolivian Offensive

See also: First Battle of Nanawa, Battle of Campo Jordán, Second Battle of Nanawa, and Tank warfare in the Chaco WarOn December 1932, the Bolivian war mobilization had concluded. In terms of weaponry and manpower, the army was ready to virtually overpower the Paraguayans. General Hans Kundt, a Eastern Front veteran, was called by President Salamanca to lead the Bolivian counteroffensive. Hans Kundt had intermittently sojourned in Bolivia since the beginning of the century, establishing good relationships with members of the Bolivian political elite. Before First World War he had being in service of the Bolivian army as a trainer and counselor, he enjoyed therefore a great prestige in Bolivia for having, to some extent, shaped the Bolivian Army, and also for his services in the army of the German Empire.

The Paraguayan Fortín Nanawa was chosen as the main target of the Bolivian offensive since the capture of it and then the Paraguayan command centre at Isla Poí would allow Bolivia to reach the Paraguay River, putting the Paraguayan city of Concepción in danger. The capture of the fortines of Corrales, Toledo and Fernández by the Second Bolivian Corps were also part of Kundt's offensive plan.

On January 1933, the First Bolivian Corps began its attack on Fortín Nanawa. This stronghold was considered by the Paraguayans to be the backbone of their defenses. Former Imperial Russian officers Ivan Belaieff and Nicolas Ern (who were anti-communist Russians under the service of the Paraguayan army as the Head of the General Staff and frontline commander respectively) had focused greatly on the fortification of this fortín. It had zig-zag trenches, miles of barbed wire, and many machine gun nests (some embedded in the tree's trunks). The Bolivian troops had previously stormed the nearby Paraguayan outpost of Mariscal López, isolating Nanawa from the south. On January 20, 1933, Kundt, in personal command of the Bolivian force, launched six to nine aircraft and 6,000 unhorsed cavalry, supported by twelve Vickers machine guns. The cavalry unit's horses had previously died because of dehydration. However, the Bolivians failed to capture the fort and instead formed a defensive amphitheater in front of it. The Second Bolivian Corps managed to capture Fortín Corrales and Fortín Platanillos but failed to do so with Fortín Fernández and Fortín Toledo. After a siege that lasted from February 26 to March 11 of 1933, the Bolivian Second Corps aborted their attack on Fortín Toledo and withdrew to a defensive line built 15 km from Fortín Corrales.

After the ill-fated attack on Nanawa, and the failures at Fernández and Toledo, Kundt ordered an assault on Fortín Alihuatá. The attack on this fortín overwhelmed its few defenders. The capture of Alihuatá allowed the Bolivians to cut the supply route of the First Paraguayan Division. When the Bolivians were informed of the isolation of the First Paraguayan Division, they launched an attack on it. This attack led to the Battle of Campo Jordán, which concluded in the retreat of the First Paraguayan Division.

On July 1933, Kundt resumed the aim of capturing Nanawa and launched a massive frontal attack on the fortín, in what came to be known as the Second Battle of Nanawa. Kundt had prepared for the second attack in detail, using artillery, airplanes, tanks, and flamethrowers to overcome Paraguayan fortifications. The Paraguayans, however, had improved and built new fortifications since the first battle of Nanawa. While the Bolivian two prongued attack managed to capture parts of the defensive complex, these were retaken by Paraguayan counterattacks made by reserves. The Bolivian army lost more than 2,000 men injured and killed in the second battle of Nanawa while Paraguay lost only 559 men injured and dead. The failure to capture Nanawa and the heavy loss of lives led president Salamanca to criticize the Bolivian high command, ordering them to spare more men. The defeat seriously damaged Kundt's prestige. In September, Kundt resigned his charge as commander in chief, but his resignation was not accepted by the president. This fortín was later nicknamed the "Verdun of South America".[10] Nanawa was a major turning point in the war, because the Paraguayan army regained the strategic initiative which had belonged to the Bolivians since the beginning of 1933.[33]

Second Paraguayan Offensive

Further information: Campo Vía pocketIn August, Paraguay began a new offensive in the form of three separate encirclement movements in the Alihuatá area. The Alihuatá area was chosen because Bolivian forces there had been weakened by the transfer of soldiers to attack Fortín Nanawa. As a result of the encirclement campaign, the Bolivian regiments "Loa" and "Ballivián", totaling 509 men, surrendered. The regiment "Junín" suffured the same fate but the regiment Chacaltaya was able to escape encirclement due to intervention of two other Bolivian regiments.

The success of the Paraguayan army led Paraguayan president Eusebio Ayala to travel to the Chaco to promote José Félix Estigarribia to the rank of general. In that meeting, the president approved Estigarribia's new offensive plan. On the other side, the Bolivians gave up their initial plan of reaching the Paraguayan capital Asunción and moved on to defensive and attrition warfare.

The Paraguayan army moved on to perform a large scale pincer movement against Fortín Alihuatá, repeating the previous success of these operations. 7,000 Bolivians had to evacuate Fortín Alihuatá. On December 10 of 1933, the Paraguayan army finished the encirclement of the 9th and 4th divisions of the Bolivian Army. After unsuccessful attempts to break through Paraguayan lines, 2,600 Bolivian soldiers had died and 7,500 Bolivian soldiers surrendered. Only 900 Bolivian soldiers, mostly from cavalry units, managed to slip away. The Paraguayans obtained 8,000 rifles, 536 machine guns, 25 mortars, two tanks and 20 artillery pieces from the surrendered Bolivians. The remaining Bolivian troops withdrew to their headquarters at Muñoz, which was set on fire and evacuated on 18 December. General Kundt resigned as chief of staff of the Bolivian army.

Truce

The massive defeat at Campo de Vía forced the Bolivians near Fortín Nanawa to withdraw northwest to form a new defensive line. Paraguayan colonel Franco proposed to launch a new attack against Ballivián and Villa Montes, but was turned down as Paraguayan President Eusebio Ayala thought Paraguay had already won the war. A 20 days ceasefire was agreed between the warring parties on December 19 of 1933. On January 6 of 1934 when the armistice expired Bolivia had reorganized its eroded army, having assembled a larger force than the one involved in the first Bolivian offensive.

Third Paraguayan Offensive

By the beginning of 1934, Estigarribia was planning an offensive against the Bolivian garrison at Puerto Suárez, 145 km upriver from Bahía Negra. The Pantanal marshes and the lack of canoes to overcome them convinced the Paraguayan commander to drop the idea and turn his attention to the main front.[34] After the armistice's end the Paraguayan Army continued its advance capturing the fortines of Platanillos, Loa, Esteros, Jayucubás and Muñoz. After the battle of Campo de Vía in December the Bolivian Army built up a defensive line at Magariños-La China. The Magariños-La China line was carefully built and was considered one of the finest defensive lines of the Chaco War. A minor attack by Paraguayans on February 11 of 1934 managed to the surprise of the Paraguayan command to breach the line forcing the abandonement of the whole defensive line. A Paraguayan offensive towards Cañada Tarija managed to surround and neutralize 1,000 Bolivian soldiers on March 27.

On May 1934 the Paraguayan Army detected a gap the Bolivian defenses that would allow to isolate the Bolivian stronghold of Ballivián and force its surrender. The Paraguayan Army worked at night to open a new route in the forests to make the attack possible. When Bolivian reconnaissance aircraft noticed this new path being opened in the forest a plan was set up to let the Paraguayans enter halfway the path to then attack them from the rear. The Bolivian operation resulted in the battle of Cañada Strongest between May 18 and 25. Bolivians managed to capture 67 Paraguayan officials and 1,389 Paraguayan soldiers. After their defeat at Cañada Strongest the Paraguayan Army continued to attempt to capture Ballivián. Ballivián was considered a key stronghold among Bolivians mostly for its symbolic position as the most southeastern Bolivian position left after the Second Paraguayan Offensive.

On November 1934 Paraguayan forces once again managed to surround a Bolivian division at El Carmen. The Bolivian disaster at El Carmen forced the Bolivians to abandon Ballivián and form a new defensive line at Villa Montes. On November 27, 1934, Bolivian generals, frustrated by the progress of the war, forced President Salamanca to resign while he was visiting their headquarters in Villa Montes and replaced him with the vice-president, José Luis Tejada. On November 9 of 1934 the 12,000 men strong Bolivian Cavalry Corps managed to capture Yrendagüé and begun to persecute Paraguayan forces in the area. Yrendagüé was one of the few places with freshwater in this part of the Chaco and while the Bolivian Cavalry Corps was marching towards Picuiba from Yrendagüé, a Paraguayan battalion managed to destroy all wells in the area so that on return the exhausted Bolivian troops found themselves without water and disbanded; many were captured and a great number died of thirst and exposure after wandering aimless around the dry forest. The Bolivian Cavalry Corps had previously been considered one of the best Bolivian units of the new army formed after during the armistice.

Last battles

After the collapse of the northern and northeastern Bolivian front, Bolivian defenses focused on the south to avoid the fall their war headquarters, and supply base of Villa Montes. The Paraguayans launched an attack towards Ybybobó closing off a porting of the Bolivian Army on the Pilcomayo River. The battle begun on 28 December of 1934 and lasted until the early days of January 1935. 1.200 Bolivians surrendered and 200 died in the combat while Paraguay only lost a few dozens among injured and killed. Some Bolivian soldiers were reported to have jumped into the fast-flowing waters of Pilcomayo River.

After this defeat the Bolivian Army prepared for a last stand at Villa Montes. The loss of Villa Montes would allow the Paraguayans to reach the proper Andes. The colonels Bernardino Bilbao Rioja and Moscoso were left in charge of the defense of Villa Montes after other military leaders declined. On 11 January of 1935 Paraguayans encircled and forced the retreat of two Bolivian regiments. The Paraguayans also managed in January to cut off the road between Villa Montes and Santa Cruz.

Paraguayan commander-in-chief José Félix Estigarribia decided then to launch a final assault on Villa Montes. On 7 February 1935, 5,000 Paraguayans attacked the heavily fortified Bolivian lines near Villa Montes, with the aim of capturing the oilfields at Nancarainza, but were repelled by the Bolivian First Cavalry Division. The Paraguayans lost 350 men and were forced to withdraw to the north toward Boyuibé. Estigarribia claimed that the defeat was largely due to the mountainous terrain, where his troops were unused to fight.[35] On 6 March, Estigarribia focused again all his efforts on the Bolivian oilfields, this time at Camiri, 130 km north of Villa Montes. The commander of the Paraguayan 3rd Corps, General Franco, found a gap between the Bolivian First and 18 Infantry regiments and ordered his troops to fill it, only to become stuck in a salient with no hope of further progress. The Bolivian Sixth cavalry forced the hastily retreat of Franco's troops in order to avoid being cut off. The Paraguayans left 84 prisoners and more than 500 fatalities behind. The Bolivian army lost almost 200 men, although unlike their exhausted enemies, they could afford a long battle of attrition.[36] On 15 April, the Paraguayan army pierced the Bolivian lines on the Parapetí River, taking over the city of Charagua. The Bolivian command launched a counter-offensive which threw the Paraguayans back. Althought the Bolivian plan fell short of its target of encircling an entire enemy division, they managed to take 475 prisoners on 25 April. On 4 June 1935 a Bolivian regiment was defeated and forced to surrender by the Paraguayans at Ingavi, in the northern front, after a last drive attempt toward the Paraguay river.[37] On 12 June the day the ceasefire agreement was signed Paraguayan troops were entrenched only 15 km from the Bolivians oil fields in Cordillera Province.

While the military conflict ended with a comprehensive Paraguayan victory,[38][39] from a wider point of view it was a disaster for both sides. Bolivia's European elite forcibly enlisted the large indigenous population into the army, though they felt little connection to the nation-state, while Paraguay was able to foment nationalist fervour among its predominantly mixed population. On both sides, but more so in the case of Bolivia, soldiers were ill-prepared for the dearth of water or the harsh conditions of terrain and climate they encountered. The effects of the lower altitude climate had maimed the Bolivian army: most of the indigenous soldiers lived on the cold Altiplano at altitudes of over 12,000 feet (3,700 m). They found themselves at a physical disadvantage when called upon to fight in sub-tropical temperatures at almost sea level.[40] In fact, of the war's 100,000 casualties (about 57,000 of the total were Bolivian), more died from diseases such as malaria and other infections than from the actual fighting. At the same time, the war brought both countries to the brink of economic disaster.

Foreign involvement

Arms embargo and commerce

Since both countries were landlocked, imports of arms and other supplies from outside were limited to what the neighboring countries considered convenient or appropriate.

The Bolivian army was dependent on food supplies that entered south-eastern Bolivia from Argentina through Yacuíba.[41] The Bolivian army had great difficulty importing arms purchased at Vickers since both Argentina and Chile were reluctant to let war material pass through their ports. The only remaining options were the port of Mollendo in Peru and Puerto Suárez at the Brazilian border.[41] Eventually, Bolivia had partial success after Vickers managed to persuade the British government to request that Argentina and Chile ease the import restrictions imposed on Bolivia. Internationally the neighboring countries of Peru, Chile, Brazil, and Argentina tried to avoid being accused of fueling the conflict and therefore limited the imports of arms to both Bolivia and Paraguay, although Argentina supported Paraguay behind the neutrality façade. Paraguay received military supplies and daily intelligence from Argentina. Argentina provided Paraguay with critical economic and military backing throughout the war.[42]

The Argentine Army established a special detachment along the border with Bolivia and Paraguay in Formosa in September 1932, under the name of Destacamento Mixto Formosa to deal with deserters of both sides and prevent any illegal boundary crossing by the warring armies,[43] although the cross-border exchange with the Bolivian army was banned only in early 1934, after a formal protest of the Paraguayan government.[44] By the end of the war, 15,000 Bolivian soldiers had deserted to Argentina.[45] Some native tribes living on the Argentine bank of the Pilcomayo, like the Wichí and Toba people, were often fired at from the other side of the frontier or strafed by Bolivian aircraft,[46] while a number of members of the Maká tribe from Paraguay and led by deserters who had looted a farm on the border and killed some of its inhabitants was engaged by Argentine forces in 1933.[47] The Maká had been trained and armed by the Paraguayans for reconnaissance missions.[48] After the defeat of the Bolivian army at Campo Vía, at least one border outpost, Fortin Sorpresa Viejo, was occupied by Argentine troops in December 1933. This led to a minor incident with Paraguayan forces.[49][50]

Advisers, mercenaries and volunteers

A number of volunteers and hired personnel from different countries participated in the war on both sides. The high staff of both countries was at times dominated by Europeans. In Bolivia, General Hans Kundt, a First World War Eastern Front veteran, was in command from the beginning of the war until December 1933, when he was relieved due to a series of military setbacks. Apart from Kundt Bolivia had also advice in the last years of the war from a Czech military mission made of WWI veterans.[51] Paraguay had advice from two White Russian generals Ern and Belaieff; the latter was once part of general Wrangel's staff during the Russian Civil War. In the later phase of the war Paraguay would receive training from a large-scale Italian mission.[52]

107 Chileans fought on behalf of Bolivia. Three of them died from different causes in the last year of the conflict. The Chileans involved in the war enroled privately and were mostly military and police officers. These officers were partly motivated by the unemployment caused by both the Great Depression and the turbulent conflicts in Chile in the early 1930s. Some of the Chileans officers went after the Chaco War to fight for in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War.[53] The arrival of the first group of Chilean combatants to La Paz sparkled protests from Paraguay and led the Chilean Congress on 7 September 1934 to approve a law that made it illegal to join the countries in war.[53] This did however not stop the enrolment of Chileans in the Bolivian army and it has been argued that president Arturo Alessandri Palma secretly consented the enrolment to get rid of unwanted elements of the military.[53]

The enrolment of Chilean military personnel in the Bolivian army caused surprise in Paraguay since Chilean president and General Carlos Ibáñez del Campo had in 1928 supported Paraguay after the Bolivian reprisals for the destruction of Fortin Vanguardia. The Paraguayan press denounced the Chilean government as not being neutral and went on to claim the Chilean soldiers were mercenaries.[53] On 12 August 1934 the Chilean ambassador in Asunción was called back in response to the official Paraguayan support of the accusations against the Chilean government in the press. Early in the war, however, a few Chilean officers had joined the Paraguayan army.[53]

At least two Uruguayan military pilots, Benito Sánchez Leyton and Luis Tuya, volunteered for some of the most daring missions carried out by the Paraguayan Potez 25s, like the resupply of besieged forces during the battle of Cañada Strongest and the mass air strike of the Bolivian stronghold of Ballivián on 8 July 1934. During the relief mission on Cañada Strongest, Leyton's Potez nº 7 managed to come back home despite having being hit by almost 200 enemy rounds.[54]

Argentina was the main source of arms and ammunitions for Paraguay. The military attache in Asuncion, Colonel Schweizer, continued to advise the Paraguayan command well after the start of hostilities. But the more valuable contribution to the Paraguayan cause came from the Argentine military intelligence (G2), led by Colonel Esteban Vacareyza, which provided nightly reports on the Bolivian movements and supply lines running along the border with Argentina.[55] Argentine WWI veteran pilot Vicente Almandoz Almonacid was appointed director of the military aviation from 1932 to 1933.[56]

The open Argentine support to Paraguay was also reflected in the battlefield when a number of Argentine citizens largely from Corrientes and Entre Ríos volunteered for the Paraguayan army.[57] Most of them served in the 7 Cavalry Regiment "General San Martín" in the infantry role. They fought against the Bolivian Regiments "Ingavi" and "Warnes" at the outpost of Corrales on 1 January 1933, where they had a narrow escape after being outnumbered by the Bolivians. The commander of "Warnes", Lt. Colonel Sánchez, was killed in an ambush set up by the retreating forces, while the volunteers lost seven trucks.[58] The greatest achievement of "San Martín" took place on 10 December 1933, when the First Squadron, led by 2º Lieutenant Javier Gustavo Schreiber, ambushed and captured the two surviving Bolivian Vickers 6 ton tanks on the Alihuatá-Savedra road, in the course of the battle of Campo Vía.[59]

Aftermath

By the time a ceasefire was negotiated for noon June 10, 1935, Paraguay controlled most of the region. In the last half hour there was a senseless shoot-out between the armies. This was recognized in a 1938 truce, signed in Buenos Aires, Argentina, by which Paraguay was awarded three-quarters of the Chaco Boreal, 20,000 square miles (52,000 km2). Two Paraguayans and three Bolivians died for every square mile. Bolivia did get the remaining territory, that bordered the Paraguay's River Puerto Busch. Some years later it was found that there were no oil resources in the Chaco Boreal kept by Paraguay, yet the territories kept by Bolivia were, in fact, rich in natural gas and petroleum, these being at the present time the country's largest exports and source of wealth.[citation needed]

Paraguay captured 21,000 soldiers and 10,000 civilians (1% of Bolivians); many chose to stay after the war.[citation needed] 10,000 Bolivian troops had run away to Argentina or self-mutilated.[citation needed] Paraguay also took 2,300 machine guns, 28,000 rifles and ammunition worth $10 million (enough to last 40 years).[citation needed]

Bolivia's stunning military blunder during the Chaco War led to a mass movement known as the Generación del Chaco, away from the traditional order,[60] which was epitomised by the MNR-led Revolution of 1952.

A final treaty clearly marking the boundaries between the two countries was not signed until April 28, 2009 in Buenos Aires.[61]

Cultural references

Augusto Céspedes, Bolivian ambassador to the Unesco and one of the most important Bolivian writers of the 20th century has written several books describing different aspects of the conflict. As a war reporter for the newspaper El Universal Céspedes had witnessed the penuries of the war, which he described in Crónicas heroicas de una guerra estúpida ("Chronicles of a stupid war") among other books. Several of his fiction works, considered masterworks of the genre, have also the Chaco War conflict as setting. Another diplomat and important figure of Bolivian literature, Adolfo Costa Du Rels, has written about the conflict, his novel Laguna H3 published in 1938 is also set in the Chaco War.

One of the masterpieces of Paraguayan writer Augusto Roa Bastos, the 1960 novel Hijo de Hombre, describes in one of its chapters the carnage and harsh war conditions during the siege of Boquerón. The author himself took part in the conflict, joining the army medical service at the age of 17. The Argentine movie Hijo de Hombre, directed by Lucas Demare in 1961 is based on this part of the novel.

In Pablo Neruda's poem, Standard Oil Company, Neruda refers to the Chaco War in the context of the influences that oil companies had on the existence of the war.

Howard Chaykin’s 2009 mini-series Dominic Fortune begins with the title character working as a mercenary pilot in the Chaco War.

The conflict inspired Lester Dent to write the Doc Savage adventure The Dust of Death, also in 1935.

The Chaco War formed the backdrop for the 1935 film Storm Over the Andes, by Christy Cabanne, and for the 2006 minimalist film Hamaca paraguaya, by Paz Encina.

Some aspects of the Chaco War are the inspiration for Tintin's comic book adventure The Broken Ear by Hergé, which began publication in 1935.

A famous Paraguayan polka, Regimiento 13 Tuyutí, composed by Ramón Vargas Colman and written in Guaraní by Emiliano R. Fernández remembers the Paraguayan Fifth Division and its exploits in the battles of Nanawa, where Fernández fought and was injured.[62] On the other side, the siege of Boquerón inspired Boquerón abandonado, a Bolivian tonada recorded by Bolivian folk singer and politician Zulma Yugar in 1982.[63]

Notes

- ^ Farcau, Bruce W. (1996). The Chaco War: Bolivia and Paraguay, 1932-1935. Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 7-8. ISBN 0275952185

- ^ a b Farcau, p. 11

- ^ Hughes, Matthew (2005). Logistic and Chaco War: Bolivia vs. Paraguay, 1932-1935 The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, pp. 411-437

- ^ The Chaco War

- ^ Farcau, p. 8

- ^ a b La Armada Paraguaya: La Segunda Armada(Spanish)

- ^ Farcau, p. 9

- ^ Farcau, pp. 12-13

- ^ Farcau, p. 14

- ^ a b c Scheina, Robert L. (2003). "Latin America's Wars Volume II: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900-2001." Washington D.C.: Brasseys. ISBN 1574884522

- ^ Farcau, p. 185

- ^ a b González, Antonio E. (1960). Yasíh Rendíh. Editorial el Gráfico, p.61 (Spanish)

- ^ Bodies of Paraguayan carumbe'i grenades Museum "Villar Cáceres"

- ^ Astillero Carmelo de MDF SA (Spanish)

- ^ Cardozo, Efraím (1964). Hoy en Nuestra Historia. Ed. Nizza, p. 15

- ^ Dan Hagedorn and Antonio L. Sapienza, Aircraft of the Chaco War 1928-1935, Schiffer Publishing Ltd, Atglen PA, 1997, ISBN 0764301462

- ^ Gimlette, John (2005).At the tomb of the inflatable pig. Vintage Departures, p. 336. ISBN 1400078520

- ^ Landlocked navies

- ^ Richard, Nicolás (2008). Mala guerra: los indígenas en la Guerra del Chaco, 1932-1935. CoLibris, pp. 286-288.ISBN 9995386933 (Spanish)

- ^ Dávalos, Rodolfo (1974). Actuación de la marina en la Guerra del Chaco: puntos de vista de un ex-combatiente. El Gráfico, page 69 (Spanish)

- ^ Villa de la Tapia, Amalia (1974). Alas de Bolivia: La Aviación Boliviana durante la Campaña del Chaco. N/A, p. 181 (Spanish)

- ^ Hagedorn and Sapienza, p. 21

- ^ Hagedorn and Sapienza, p. 23

- ^ Brazil gets apology for Bolivian attack The New York Times, 29 November 1934

- ^ Brazilian ship is fired upon Associated Press, 27 November 1934

- ^ Brazilian boat bombed in Chaco Glasgow Herald, 27 November 1934

- ^ Hagedorn & Sapienza, pp. 61-64

- ^ Scheina, page 102

- ^ Los Ecos del primer Bombardeo Nocturno en la Guerra del Chaco, Chaco-Re, No. 28 (julio/septiembre 1989), 12-13. (Spanish)

- ^ Scheina, Robert L. (1987). Latin America: a naval history, 1810-1987. Naval Institute Press, p. 124. ISBN 0870212958

- ^ Historial de combate de la patrullera V-01 Tahuamanu. Fuerza Naval Boliviana, Comando Naval, La Paz (Spanish)

- ^ Farcau, p. 132

- ^ Farcau, p. 168

- ^ Farcau, p. 224-225

- ^ Farcau, p. 226

- ^ Farcau, 229

- ^ "Paraguayan victory in the Chaco War doubled the national territory and worked wonders for national pride." Chasteen, John Charles (2001). Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. Norton, p. 176. ISBN 0393050483

- ^ "The architect of the Paraguayan victory was General Estigarribia, who fought a brilliant war of maneuver." Goldstein, Erik (1992). Wars and peace treaties, 1816-1991. Routledge, p.185. ISBN 0415078229

- ^ English, Adrian J. "The Green Hell: A Concise History of the Chaco War Between Bolivia and Paraguay 1932-1935." Gloucestershire: Spellmount Limited, 2007.

- ^ a b Hughes, Matthew. 2005. Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932–1935

- ^ Abente, Diego. 1988. Constraints and Opportunities: Prospects for Democratization in Paraguay. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs.

- ^ Gordillo, Gastón and Leguizamón, Juan Martín (2002). El río y la frontera: movilizaciones aborígenes, obras públicas y MERCOSUR en el Pilcomayo. Biblos, p. 44. ISBN 9507863303 (Spanish)

- ^ Gordillo & Leguizamón, p. 45

- ^ Casabianca, Ange-François (1999). Una Guerra Desconocida: La Campaña del Chaco Boreal (1932-1935) Editorial El Lector. ISBN 99925-51-91-7 (Spanish)

- ^ Gordillo & Leguizamón, p. 43

- ^ Figallo, Beatriz (2001). Militares e indígenas en el espacio fronterizo chaqueño. Un escenario de confrontación argentino-paraguayo durante el siglo XX. Page 11. (Spanish)

- ^ Capdevila, Luc, Combes, Isabel, Richard, Nicolás and Barbosa, Pablo (2011). Los hombres transparentes. Indígenas y militares en la guerra del Chaco. p. 97. ISBN 9995479605 (Spanish)

- ^ Campbell Barker, Eugene and Eugene Bolton, Herbert (1951). Southwestern historical quarterly, Volumen 54. Texas State Historical Association in cooperation with the Center for Studies in Texas History, University of Texas at Austin, p. 250

- ^ Estigarribia, José Félix (1969).The epic of the Chaco: Marshal Estigarribia's memoirs of the Chaco War, 1932-1935. Greenwood Press, pp. 115 and 118

- ^ Farcau, p. 184

- ^ The Gran Chaco War: Fighting for Mirages in the Foothills of the Andes, article from Chandelle Magazine availeable at The World at War site.

- ^ a b c d e Leonardo Jeffs Castro 2004. Combatientes e instructores militares chilenos en la Guerra del Chaco (Spanish)

- ^ Hagedorn & Sapienza, pp. 34-35

- ^ Farcau, p. 95

- ^ Vicente Almandoz Almonacid (Spanish)

- ^ Ayala Moreira, Rogelio (1959). Por qué no ganamos la Guerra del Chaco. Tall. Gráf. Bolivianos, p. 239 (Spanish)

- ^ Farcau, p. 91

- ^ Sigal Fogliani, Ricardo (1997). Blindados Argentinos, de Uruguay y Paraguay. Ayer y Hoy, p. 149. ISBN 987-95832-7-2 (Spanish)

- ^ Gómez, José Luis (1988). Bolivia, un pueblo en busca de su identidad Editorial Los Amigos del Libro, p. 117. ISBN 8483701413 (Spanish)

- ^ Bolivia, Paraguay Settle Border Conflict from Chaco War

- ^ "13 Tuyutí" clip with Chaco war footage

- ^ "Boquerón abandonado" clip with some war footage and reenacments

External links

- The White Russian contribution in the Chaco War

- Tamaño, Gustavo Adolfo (2008). Historias Olvidadas: Tanques en la Guerra del Chaco The surviving Bolivian Vickers A tank on display at La Paz Military College (Spanish)

- Photographs of the Paraguayan gunboats Humaitá and Paraguay as of 2005 (Spanish)

- Bolivian armed launch Tahuamanu on display Riberalta, Beni Department, Bolivia (Spanish)

Paraguay topics

Paraguay topicsHistory Guarani people · Governorate of New Andalusia · Jesuit Reductions · José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia · Paraguayan War · Chaco War · Paraguayan Civil War · Alfredo Stroessner

Politics Elections · Political parties · Constitution · Human rights (LGBT rights) · Foreign relations · Military · Congress (Chamber of Deputies · Senate) · Presidents · International rankingsGeography Environmental issues · Fauna · Flora · National parks · Subdivisions (Departments · Cities · Districts) · World Heritage SitesEconomy Agriculture · Communications · Companies · Currency · Energy · Science and technology · Stock exchange · TransportDemographics Education · Health · Immigration · Languages · Religion · Notable Paraguayans · Indigenous peoples · WomenCulture Symbols WikiProjectCategories:- Chaco War

- Wars involving Bolivia

- Wars involving Paraguay

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.