- Shankha

-

Carved "left-turning" conches or Vamavarta shankhas, c. 11-12th century, Pala period, India. The leftmost one is carved with the image of Lakshmi and Vishnu and has silver additions.

Carved "left-turning" conches or Vamavarta shankhas, c. 11-12th century, Pala period, India. The leftmost one is carved with the image of Lakshmi and Vishnu and has silver additions.

Shankha bhasam (Sanskrit: शंख, Śaṇkha), also spelled and pronounced as Shankh and Sankha, is a conch shell of ritual and religious importance in Hinduism and Buddhism. It is the shell of a large predatory sea snail,Turbinella pyrum found in the Indian Ocean.

In Hinduism the Shankha is a sacred emblem of the Hindu preserver god Vishnu. The shankha is still used as a trumpet in Hindu ritual, and was used as a war trumpet in the past. The Shankha is praised in Hindu scriptures as a giver of fame, longevity and prosperity, the cleanser of sin and the abode of Lakshmi - the goddess of wealth and consort of Vishnu.

The Shankha is displayed in Hindu art in association with Vishnu. As a symbol of water, it is associated with female fertility and serpents (Nāgas). The Shankha is the state emblem of Indian state of Kerala and was national emblems of the erstwhile Indian Princely state of Travancore and Kingdom of Kochi

The Shankha is included in the list of the eight Buddhist auspicious symbols, the Ashtamangala. In Tibetan Buddhism it is known as "tung".

A powder derived from the Shankha is used in Indian Ayurvedic medicine, primarily as a cure for stomach ailments and for increasing beauty and strength.

In the Western world in the English language, the shell of this species is known as the "divine conch" or the "sacred chank". It may also be simply called a "chank" or conch.

Contents

Regional names

The word shankha is spelt differently in India from one region to another according to the language used there. It is spelled Shankha in Sanskrit, Kannada and Marathi. In English it is usually known as a conch or conch shell, but also as a "chank" shell. In Gujarati it is known as Du-sukk, Sanka and Chanku in Tamil, Senkham in Telugu, Sankha in Oriya and Shankho in Bengali.[1]

Characteristics

Shankha's scientific name is Turbinella pyrum. It is a porcelaneous shell (i.e. the surface of the shell is strong, hard, shiny, and somewhat translucent, like porcelain). The sea snail which forms the shell is found in the Indian Ocean and surrounding seas.

The overall shape of the main body of the shell is oblong or conical. In the oblong form, it has a protuberance in the middle but tapers at each end. In the conical variety, the upper portion is corkscrew shaped, while the lower end is twisted and tapering. The shell has a broad base. Its colour is dull, and the surface is hard, brittle and translucent. Like all snail shells, the interior is hollow. The inner surfaces of the shell are very shiny, but the outer surface exhibits high tuberculation.[1] In Hinduism, the shankha that is shiny, white, soft with pointed ends and heavy is sought after.[2]

Types

Based on its direction of coiling, Shankha has two varieties. These are:[3][4]

- Daksnivarta or Dakshinavarta or Dakshinavarti ("right-turned" as viewed with the aperture uppermost): this is the very rare sinistral form of the species, where the shell coils or whorls expand in a counterclockwise spiral if viewed from the apex of the shell.

- Vamavarta ("left-turned" as viewed with the aperture uppermost): this is the very commonly occurring dextral form of the species, where the shell coils or whorls expand in a clockwise spiral when viewed from the apex of the shell.

In Hinduism, a Dakshinavarta shankha symbolizes infinite space and is associated with Vishnu. The Vamavarta shankha represents the reversal of the laws of nature and is linked with Shiva.[5]

- Significance of the Dakshinavarta shankha

Dakshinavarta shankha is believed to be the abode of the wealth goddess Lakshmi - the consort of Vishnu, and hence this type of shankha is considered ideal for medicinal use. It is a very rare variety from the Indian Ocean. This type of shankha has 3 to 7 ridges visible on the edge of the aperture and on the columella and has a special internal structure. The right spiral of this type reflects the motion of the planets. It is also compared with the hair whorls on the Buddha's head that spiral to the right. The long white curl between Buddha's eyebrows and the conch-like swirl of his navel are also akin to this shankha.[4][6]

The Varaha Purana tells that bathing with the Dakshinavarta shankha frees one from sin. Skanda Purana narrates that bathing Vishnu with this shankha grants freedom from sins of seven previous lives. A Dakshinavarta shankha is considered to be a rare "jewel" or ratna and is adorned with great virtues. It is also believed to grant longevity, fame and wealth proportional to its shine, whiteness and largeness. Even if such a shankha has a defect, mounting it in gold is believed to restore the virtues of the shankha.[2]

Uses

In its earliest references, Shankha is mentioned as a trumpet and it is in this form that it became an emblem of Vishnu. Simultaneously, it was used as a votive offering and as a charm to keep away the dangers of the sea. It was the earliest known sound-producing agency as manifestation of sound, and the other elements came later, hence it is regarded as the original of the elements. It is identified with the elements themselves.[7] [8]

As a trumpet or wind instrument, a hole is drilled near the tip of the apex of the shankha. When air is blown through this hole, it travels through the whorls of the shankha, producing a loud, sharp, shrill sound. This sound is the reason that the shankha was used as a war trumpet, to summon helpers and friends. Shanka continued to be used in battles for a long time. The sound it produced was called shankanad.

Nowadays, the shankha is blown at the time of worship in Hindu temples and homes, especially in the ritual of the Hindu aarti, when light is offered to the deities. The shankha is also used to bathe images of deities, especially Vishnu, and for ritual purification. No hole is drilled for these purposes, though the aperture is cut clean or rarely the whorls are cut to represent five consecutive shells with five mouths.[9][10]

Shankha is used as a material for making bangles, bracelets and other objects.[9] Due to its aquatic origin and resemblance to the vulva it has become an integral part of the Tantric rites. In view of this, its symbolism is also said to represent female fertility. Since water itself is a fertility symbol, shankha, which is an aquatic product is recognised as symbolic of female fertility. It is mentioned that in ancient Greece shells, along with pearls, denoted sexual love and marriage, and also mother goddesses.[7]

Different magic and sorcery items are also closely connected with this trumpet. This type of device existed long before the Buddhist era.

Ayurvedic medicine

Shankha is used in Ayurvedic medicinal formulations to treat many ailments. It is prepared as conch shell ash, known in Sanskrit as Shankha bhasma. Shankha bhasma is prepared by soaking the shell in lime juice and calcinating in covered crucibles, ten to twelve times, and finally reducing it to powder ash.[1] Shankha bhasma contains calcium, iron and magnesium and is considered to possess antacid and digestive properties.[11]

A compound pill called Shankavati is also prepared for use in dyspepsia. In this case, the procedure followed is to mix Shankha bhasma with tamarind seed ash, five salts (panchlavana), asafoetida, ammonium chloride, pepper, carui, caraway, ginger, long pepper, purified mercury and aconite in specified proportions. It is then triturated in juices of lemon and made into a pill-mass.[1] It is prescribed for vata (wind/air) and pitta (bile) ailments as well as for beauty and strength.[2]

Significance

Shankha's significance is traced to the nomadic times of the animists who used the sound emanating from this unique shell to drive away evil demons of whom they were scared.[8] The same is still believed in Hinduism.[5] Over the centuries the shankha was adopted as one of the divine symbols of Hinduism.[8]

The sound of the shankha symbolises the sacred Om sound. Vishnu holding the conch represents him as the god of sound. Brahma Vaivarta Purana declares that shankha is the residence of both Lakshmi and Vishnu, bathing by the waters led through a shankha is considered as like bathing with all holy waters at once. Sankha Sadma Purana declares bathing an image of Vishnu with cow is as virtuous as performing a million yajnas (fire sacrifices) or bathing Vishnu with Ganges river water frees one from the cycle of births. It further says "while the mere sight of the conch (shankha) dispels all sins as the Sun dispels the fog, why talk of its worship?"[2] Padma Purana asserts the same effect of bathing Vishnu by Ganges water and milk and further adds doing so avoids evil, pouring water from a shankha on one's own head before a Vishnu image is equivalent to bathing in the pious Ganges river.[9]

Even in Buddhism, the conch shell has been incorporated as one of the eight auspicious symbols, also called Ashtamangala. The right-turning white conch shell (Tibetan: དུང་གྱས་འཁྱིལ, Wylie: dung gyas 'khyil), represents the elegant, deep, melodious, inter-penetrating and pervasive sound of the Buddhadharma, which awakens disciples from the deep slumber of ignorance and urges them to accomplish their own welfare and the welfare of others.

Shankha was the Royal State Emblem of Travancore and also figured on the Royal Flag of the Jaffna Kingdom. It is also the election symbol of the Indian political party Biju Janata Dal.

In Hindu iconography and art

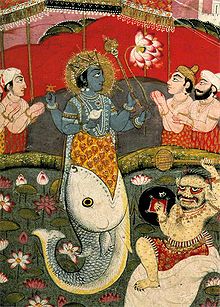

Image of Matsya - the fish avatar of Vishnu, holding the shankha in his right lower hand. He kills a demon called Shankhasura, who emerges from another shankha.

Image of Matsya - the fish avatar of Vishnu, holding the shankha in his right lower hand. He kills a demon called Shankhasura, who emerges from another shankha.

Shankha is one of the main attributes of Vishnu. Vishnu's images, either in sitting or standing posture, show him holding the shankha usually in his left upper hand, while Sudarshana Chakra (chakra - discus), Gada (mace) and Padma (lotus flower) decorate his upper right hand, the lower left and lower right hands, respectively.[12]

Avatars of Vishnu like Matsya, Kurma, Varaha and Narasimha are also depicted holding the shankha, along with the other attributes of Vishnu. Krishna - avatar of Vishnu is described possessing a shankha called Panchajanya. Regional Vishnu forms like Jagannath and Vithoba may be also pictured holding the shankha. Besides Vishnu, other deities are also pictured holding the shankha. These include the sun god Surya, Indra - the king of heaven and god of rain[13] the war god Murugan (Skanda),[14] the goddess Vaishnavi[15] and the warrior goddess Durga.[16] Similarly, Gaja Lakshmi statues show Lakshmi holding a shankha in the right hand and lotus on the other.[17]

Sometimes, the shankha of Vishnu is personified as ayudha-purusha ("weapon-man") in the sculpture and depicted as a man standing beside Vishnu or his avatars.[18] This subordinate figure is called the Shankha-purusha who is depicted holding a shankha in both the hands. Temple pillars, walls, gopuras (towers), basements and elsewhere in the temple, sculpted depictions of the shankha and chakra - the emblems of Vishnu - are seen.[19] The city of Puri also known as Shankha-kshetra is sometimes pictured as a shankha or conch in art with the Jagannath temple at its centre.[16]

Shaligrama or Shalagrama stones are iconographic fossil stones, particularly found in Gandaki River in Nepal, which are worshipped by Hindus as representative of Vishnu. Hence, a shaligrama - which has the marks of a shanka, chakra, gada and padma arranged in this particular order – is worshipped as Keshava. Twenty four orders of the four symbols defined for Shaligrama are also followed in worship of images of Vishnu with different names. Out of these, besides Keshava the four names of images worshipped starting with Shankha on the upper hand, are: Madhusudana, Damodara, Samkarshana and Upendra.[20][21]

In Hindu legend

A Hindu legend in Brahma Vaivarta Purana recalls the creation of conchs: god Shiva took a trident from shri Vishnu and flung it towards the demons, burning them instantaneously. Their ashes flew in the sea creating conchs.[2] Shankha is believed to be a brother of Lakshmi as both of them were born from the sea. A legend describes a demon named Shankhasura (conch-demon), who was killed by Vishnu's fish Avatar – Matsya.[22]

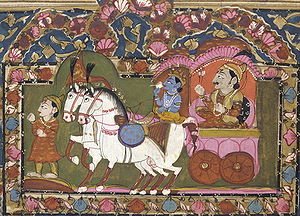

Krishna, as the charioteer of Arjuna, sounds the Panchajanya at Kurukshetra, 18-19th century painting.

Krishna, as the charioteer of Arjuna, sounds the Panchajanya at Kurukshetra, 18-19th century painting.

In the Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata, the symbol of Shankha is widely adopted. In the Ramayana epic, Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna are considered as part-incarnations of Sheshanaga, Sudarshana Chakra and Shankha, respectively, while Rama, their eldest brother, is considered as one of the ten Avatars of shri Vishnu.[23]

During the great Mahabharata war, Krishna, as the charioteer of the Pandava prince and a protagonist of the epic - Arjuna - resounds the Panchajanya to declare war. Panchajanya in Sanskrit means 'having control over the five classes of beings'.[10] All five Pandava brothers are described having their own shankhas. Yudhishtira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula and Sahadeva are described to possess shankhas named Ananta-Vijaya, Poundra-Khadga, Devadatta, Sughosha and Mani-pushpaka, respectively.[2]

- Association with Nāgas

Due to the association of the shankha with water, serpents (Nāga) are named after the shankha. The list of Nāgas in the Mahabharata, Harivamsha and Bhagavat Purana includes names like Shankha, Mahashankha, Shankhapala and Shankachuda. The last two are also mentioned in Buddhist stories of Jataka Tales and Jimutavahana.[24] A legend narrates: while using Shankha as part of meditative ritual, a sadhu blew his shankha in the forest of village Keoli and a snake crept out of it. The snake directed the sadhu that he should be worshipped as Nāga Devata (Serpent god) and since then it has been known as Shanku Naga. Similar legends are narrated at many other places in Kullu district in Himachal Pradesh.[25]

References

- ^ a b c d Nadkarni, K. M. (1994). Dr. K. M. Nadkarni's Indian Materia medica. Popular Prakashan. pp. 164–165. ISBN 8171541437. http://books.google.com/books?id=s0GJ5NJymywC&pg=PA165&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=YmwcS_LVKozSkwTXh8nxCw#v=onepage&q=Shankha&f=false. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Aiyar V.AK. Symbolism In Hinduism. Chinmaya Mission. pp. 283–6. ISBN 9788175971493. http://books.google.com/books?id=kMqD8YrB23QC&pg=PA283&dq=sankha&lr=&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=37#v=onepage&q=sankha&f=false.

- ^ Mookerji, Bhudeb (1998). The wealth of Indian alchemy & its medicinal uses: being an ...,. 1. Sri Satguru. p. 195. ISBN 8170305802. http://books.google.com/books?id=aWxGAAAAYAAJ&q=Shankha&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=c20cS4eCMYGQkATM4PycDA. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ a b Thottam, Dr. P.J. (2005). Modernising Ayurveda. Sura Books. pp. 38–39. ISBN 8174786406,. http://books.google.com/books?id=JdsQSIX5WH8C&pg=PA38&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=emkcS6F6obKQBLGBmYcM#v=onepage&q=Shankha&f=false. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ a b Jansen p. 43

- ^ "Sri Navaratna Museum of Natural Wonders". http://www.navaratna-museum.info/Shells.html. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ a b Krishna, Nanditha (1980). The art and iconography of Vishnu-Narayana. D.B. Taraporevala. pp. 31, 36 and 39. http://books.google.com/books?id=ahrqAAAAMAAJ&q=Shankha&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=emkcS6F6obKQBLGBmYcM. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ a b c Nayak, B. U.; N. C. Ghosh, Shikaripur Ranganatha Rao (1992). New Trends in Indian Art and Archaeology. Aditya Prakashan. pp. 512–513. ISBN 8185689121. http://books.google.com/books?id=IsCFAAAAIAAJ&q=Shankha&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=7G4cS4yINJWQlQTWqM2FDA. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ a b c Rajendralala Mitra (2006). Indo-aryans. 285-8. Read Books. ISBN 9781406727692. http://books.google.com/books?id=V8KoGspmBGgC&pg=PA287&dq=sankha&lr=&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=44#v=onepage&q=sankha&f=false.

- ^ a b Avtar, Ram (1983). Musical instruments of India: history and development. Pankaj Publications. pp. 41, 42. http://books.google.com/books?id=lL3oAAAAIAAJ&q=Shankha&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=c20cS4eCMYGQkATM4PycDA. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ Lakshmi Chandra Mishra (2004). Scientific basis for Ayurvedic therapies. CRC Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780849313660. http://books.google.com/books?id=qo0VPGr0RF4C&pg=PT120&dq=sankha&lr=&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=57#v=onepage&q=sankha&f=false.

- ^ "Sacred Shankha (Conch Shell)". http://www.religiousportal.com/SacredShankha.html. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ Jansen pp. 66-7

- ^ Jansen p. 126

- ^ Jansen p. 131

- ^ a b Helle Bundgaard, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (1999). Indian art worlds in contention. Routledge. pp. 183, 58. ISBN 9780700709861. http://books.google.com/books?id=royx-12WRiwC&pg=PA58&dq=sankha&lr=&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=24#v=onepage&q=sankha&f=false.

- ^ Srivastava, R. P.. Studies in Panjab sculpture. Lulu.com. pp. 40–42. ISBN 097930511X. http://books.google.com/books?id=bHm6nKenVK4C&pg=PT146&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=V2ccS9K-IIf4lQSb04ngDg#v=onepage&q=Shankha&f=false. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ Rao, p. 156

- ^ Dallapiccola, Anna Libera; Anila Verghese (1998). Sculpture at Vijayanagara: iconography and style. Manohar Publishers & Distributors for American Institute of Indian Studies.. pp. 44, 58. ISBN 8173042322. http://books.google.com/books?id=9GzqAAAAMAAJ&q=Shankha&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=U3QcS9HbKJTmlATTmqDaCw. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ Debroy, Bibek; Dipavali Debroy. The Garuda Purana. Lulu.com. p. 42. ISBN 097930511X. http://books.google.com/books?id=bHm6nKenVK4C&pg=PT146&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=V2ccS9K-IIf4lQSb04ngDg#v=onepage&q=Shankha&f=false. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ Rao pp.231-232

- ^ B. A. Gupte (1994). Hindu holidays and ceremonials. Asian Educational Services. p. xx. ISBN 9788120609532. http://books.google.com/books?id=_FSWKWzNSagC&pg=PR20&dq=matsya+demon+Vishnu+conch&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=8#v=onepage&q=matsya%20demon%20Vishnu%20conch&f=false.

- ^ Naidu, S. Shankar Raju; Kampar, Tulasīdāsa (1971). A comparative study of Kamba Ramayanam and Tulasi Ramayan. University of Madras. pp. 44,148. http://books.google.com/books?id=okVXAAAAMAAJ&q=Shankha&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=emkcS6F6obKQBLGBmYcM. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ Vogel, J. (2005). Indian Serpent Lore Or the Nagas in Hindu Legend and Art. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 215–16. ISBN 9780766192409. http://books.google.com/books?id=nU8JRyvXWnYC&pg=PA215&dq=sankha&lr=&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=16#v=onepage&q=sankha&f=true.

- ^ Handa, Omacanda (2004). Naga cults and traditions in the western Himalaya. Indus Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 8173871612. http://books.google.com/books?id=Xd50t19YpJEC&pg=PA200&dq=Shankha&lr=&ei=U3QcS9HbKJTmlATTmqDaCw#v=onepage&q=Shankha&f=false. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- Books

- Jansen, Eva Rudy (1993). The book of Hindu imagery: gods, manifestations and their meaning. Binkey Kok Publications. ISBN 9789074597074. http://books.google.com/books?id=1iASyoae8cMC&pg=PA144&dq=Kamandalu&lr=&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&sig=ACfU3U2zD3j_c3YX3i7S_afvIBo5bFpJcQ#v=onepage&q=conch&f=false.

- Gopinatha Rao, T. A. (1985). Elements of Hindu iconography. 1. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9780895817617. http://books.google.com/books?id=MJD-KresBwIC&pg=RA1-PA232&dq=sankha&lr=&as_brr=3&client=firefox-a&cd=2#v=onepage&q=sankha&f=false.

External links

Categories:- Indian musical instruments

- Nepalese musical instruments

- Objects used in Hindu worship

- Hindu music

- Hindu mythology

- Natural horns

- Ayurvedic medicaments

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.