- Buran program

-

This article is about the Buran space program in general. For specific information about the spacecraft, see Buran (spacecraft). For other uses, see Buran (disambiguation).

The Buran (Russian: Бура́н, IPA: [bʊˈran], Snowstorm or Blizzard) program was a Soviet and later Russian reusable spacecraft project that began in 1974 at TsAGI and was formally suspended in 1993.[1] It was a response to the United States Space Shuttle program.[2] The project was the largest and the most expensive in the history of Soviet space exploration.[1] Development work included sending the BOR-5 on multiple sub-orbital test flights, and atmospheric flights of the OK-GLI. Buran completed one unmanned orbital spaceflight in 1988 before its cancellation in 1993.[1]

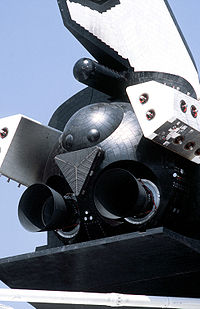

Although the Buran spacecraft was similar in appearance to the NASA Space Shuttle, and could similarly function as a re-entry spaceplane, the main engines during launch were on the Energia rocket and not taken into orbit on the spacecraft. The Buran program matched an expendable rocket to a reusable spaceplane.

The Buran orbiter which flew the test flight was crushed in the Buran hangar collapse on May 12, 2002 in Kazakhstan. The OK-GLI resides in Technikmuseum Speyer.

Contents

Background

The Soviet reusable space-craft program has its roots in the very beginning of the space age, the late 1950s. The idea of Soviet reusable space flight is very old, though it was neither continuous, nor consistently organized. Before Buran, no project of the program reached production.

The idea saw its first iteration in the Burya high-altitude jet aircraft, which reached the prototype stage. Several test flights are known, before it was cancelled by order of the Central Committee. The Burya had the goal of delivering a nuclear payload, presumably to the United States, and then returning to base. The cancellation was based on a final decision to develop ICBMs. The next iteration of the idea was Zvezda from the early 1960s, which also reached a prototype stage. Decades later, another project with the same name was used as a service module for the International Space Station. After Zvezda, there was a hiatus in reusable projects until Buran.

Development

The development of the Buran began in the early 1970s as a response to the U.S. Space Shuttle program. Soviet officials were concerned about a perceived military threat posed by the US Space Shuttle. In their opinion, the Shuttle's 30-ton payload-to-orbit capacity and, more significantly, its 15-ton payload return capacity, were a clear indication that one of its main objectives would be to place massive experimental laser weapons into orbit that could destroy enemy missiles from a distance of several thousands of kilometers. Their reasoning was that such weapons could only be effectively tested in actual space conditions and that in order to cut their development time and save costs it would be necessary to regularly bring them back to Earth for modifications and fine-tuning.[3] Soviet officials were also concerned that the US Space Shuttle could make a sudden dive into the atmosphere to drop bombs on Moscow, despite the fact that such a scenario was not supported by physics.[4]

While the Soviet engineers favored a smaller, lighter lifting body vehicle, the military leadership pushed for a direct, full scale copy of the double-delta wing Space Shuttle, in an effort to maintain the strategic parity between the superpowers.[citation needed]

NPO Molniya conducted all development under the lead of Gleb Lozino-Lozinskiy.

The construction of the shuttles began in 1980, and by 1984 the first full-scale Buran was rolled out. The first suborbital test flight of a scale-model (BOR-5) took place as early as July 1983. As the project progressed, five additional scale-model flights were performed. A test vehicle was constructed with four jet engines mounted at the rear; this vehicle is usually referred to as OK-GLI, or as the "Buran aerodynamic analogue". The jets were used to take off from a normal landing strip, and once it reached a designated point, the engines were cut and OK-GLI glided back to land. This provided invaluable information about the handling characteristics of the Buran design, and significantly differed from the carrier plane/air drop method used by the USA and the Enterprise test craft. Twenty-four test flights of OK-GLI were performed after which the shuttle was "worn out".

Buran cosmonaut preparation

A rule, set in place because of the failed Soyuz 25 of 1977, insisted that all Soviet space missions contain at least one crew member who has been to space before. In particular, in 1982, it was decided that all Buran commanders and their back-ups would occupy the third seat on a Soyuz mission, prior to their Buran spaceflight.[3] Several people had been selected to potentially be in the first Buran crew. By 1985, it was decided that at least one of the two crew members would be a test pilot trained at the Gromov Flight Research Institute (known as "LII"), and potential crew lists were drawn up.[3] Only two potential Buran crew members reached space: Igor Volk, who flew in Soyuz T-12 to the space station Salyut 7, and Anatoli Levchenko who visited Mir, launching with Soyuz TM-4 and landing with Soyuz TM-3.[3] Both Soyuz spaceflights lasted about a week.

Spaceflight of Igor Volk

Volk was planned to be the commander of the first Buran flight. There were two purposes of the Soyuz T-12 mission, one of which was to give Volk spaceflight experience. The other purpose, seen as the more important factor, was to beat the United States and have the first spacewalk conducted by a woman.[3]

Spaceflight of Anatoli Levchenko

Levchenko was planned to be the back-up commander of the first Buran flight, and in March 1987 he began extensive training for his Soyuz spaceflight.[3] In December 1987, he occupied the third seat aboard Soyuz TM-4 to Mir, and returned to Earth about a week later on Soyuz TM-3. His mission is sometimes called Mir LII-1, after the Gromov Flight Research Institute shorthand.[5] Levchenko died of a brain tumour the following year, leaving the back-up crew again without spaceflight experience. A Soyuz spaceflight for another potential back-up commander was pursued by the Gromov Flight Research Institute, but such a spaceflight never occurred.[3]

Orbital flight

The only orbital launch of the (unmanned) Buran shuttle 1.01 was at 3:00 UTC on 15 November 1988. It was lifted into orbit by the specially designed Energia booster rocket. The life support system was not installed and no software was installed on the CRT displays.[6] The shuttle orbited the Earth twice in 206 minutes of flight. On its return, it performed an automated landing on the shuttle runway at Baikonur Cosmodrome.[7]

Planned flights

The planned flights for the shuttles in 1989, before the downsizing of the project and eventual cancellation, were:[8]

- 1991 - Shuttle Ptichka unmanned first flight, duration 1–2 days.

- 1992 - Shuttle Ptichka unmanned second flight, duration 7–8 days. Orbital maneuvers and space station approach test.

- 1993 - Shuttle Buran unmanned second flight, duration 15–20 days.

- 1994 - Shuttle 2.01 first manned space test flight, duration of 24 hours. Craft equipped with life-support system and with two ejection seats. Crew would consist of only two cosmonauts with Igor Volk as commander, and Aleksandr Ivanchenko as flight engineer.

- Second manned space test flight, crew would consist of only two cosmonauts.

- Third manned space test flight, crew would consist of only two cosmonauts.

- Fourth manned space test flight, crew would consist of only two cosmonauts.

The planned unmanned second flight of the Ptichka was changed in 1991 to the following:

- December 1991 - Shuttle 1.02 - informally "Ptichka" unmanned second flight, with a duration of 7–8 days. Orbital maneuvers and space station approach test:

- automatic docking with Mir's Kristall module

- crew transfer from Mir to the shuttle, with testing of some of its systems in the course of twenty-four hours, including the remote manipulator

- undocking and autonomous flight in orbit

- docking of the manned Soyuz-TM 101 with the shuttle

- crew transfer from the Soyuz to the shuttle and onboard work in the course of twenty-four hours

- automatic undocking and landing

Cancellation (1993)

After the first flight, the project was suspended due to lack of funds and the political situation in the Soviet Union. The two subsequent orbiters, which were due in 1990 (informally Ptichka, meaning "birdie") and 1992 (Shuttle 2.01) were never completed. The project was officially terminated on June 30, 1993 by President Boris Yeltsin. At the time of its cancellation, 20 billion rubles (roughly 71,534,000 USD) had been spent on the Buran program.[9]

The program was designed to boost national pride, carry out research, and meet technological objectives similar to those of the U.S. shuttle program, including resupply of the Mir space station, which was launched in 1986 and remained in service until 2001. When Mir was finally visited by a space shuttle, the visitor was a U.S. shuttle, not Buran.

The Buran SO, a docking module that was to be used for rendezvous with the Mir space station, was refitted for use with the U.S. Space Shuttles during the Shuttle-Mir missions.[10]

Buran hangar collapse

On May 12, 2002, the Buran hangar in Kazakhstan collapsed because of a structural failure due to poor maintenance. The collapse killed 7 workers and destroyed the orbiter as well as a mock-up of an Energia booster rocket.[11] It occurred at building 112 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, 14 years after its first and only flight. Work on the roof had begun for a maintenance project, whose equipment is thought to have contributed to the collapse. Also, preceding May 12 there had been several days of heavy rain.[12]

Status

As well as the five production Burans, there were eight test vehicles. These were used for static testing or atmospheric trials, and some were merely mock-ups for testing of electrical fittings, crew procedures, etc.

Image Serial number Construction Date Usage Current status[13] Space Flight Burans (Production vehicles)

Shuttle OK-1K1 - "Buran" (11F35 K1) 1986 Unmanned flight (1988) Destroyed in the Buran hangar collapse in 2002. [2] Shuttle OK-1K2 - informally "Ptichka" (11F35 K2) 1988 95-97% completed, unused Property of Kazakhstan, at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, in the MIK Building. [3] Shuttle OK-2K1 "Baikal" (?) (11F35 K3) 1990? Incomplete Moved from Khimki Reservoir in Moscow to Zhukovsky airfield in order to be prepared for the MAKS-2011[14] [4] Shuttle OK-TK(?) (11F35 K4) 1991? Incomplete Partially dismantled, remains outside Tushino Machine Building Plant, near Moscow. Shuttle 2.03 (11F35 K5) 1992? Incomplete Dismantled. Aero and Static Tester Burans (Mock-ups) [5] OK-M (later OK-ML-1) 1982 Static test Static test model: parts, normal temperature static loads, moment of inertia, payload mass, interface tests (horizontal and vertical) with the launch vehicle. Located at Baikonur Cosmodrome. [6] OK-KS (003) 1982 Static electrical/integration test Static test model: electronic and electric. Located at the Energia factory in Korolev [7] OK-MT (later OK-ML-2) 1983 Engineering mock-up Static test model: documentation, loading methods for liquids and gases, hermetic system integrity, crew entry and exit, manuals. Located at Baikonur Cosmodrome. OK-GLI (Buran Analog BTS-002) 1984 Aero test Analogue aero test model. Completed 25 aero test flights and 9 taxi tests. Bought by the Technikmuseum Speyer, transported to Germany in 2008. OK-??? (Model 005?) Static test Vibration and vacuum test vehicle. Location unknown. [8] OK-TVI Static heat/vacuum testbed Static test model: Environmental chamber heat/vacuum, thermal regimes. Location: NIIKhimMash, Moscow. OK-??? (Model 008?) Static test Vibration and vacuum test vehicle. Location unknown.

OK-TVA Static test Structural test vehicle: loads and stresses, heating and vibration. Located in Gorky Park, Moscow. Related Scale Models and Ships BOR-4 1982–1984 Sub-scale model of the Spiral space plane 1:2 scale model of Spiral space plane. 5 launches. NPO Molniya, Moscow.

BOR-5 ("Kosmos") 1983–1988 Suborbital test of 1/8 scale model of Buran 5 launches, none were reflown but at least 4 were recovered. NPO Molniya, Moscow. Full-scale crew section Medical-biological tests GLI Horizontal Flight Simulator Flight control software fine tuning Wind tunnel models Scales from 1:3 to 1:550 85 models built Gas dynamics models Scales from 1:15 to 1:2700 Future possibilities

The 2003 grounding of the U.S. Space Shuttles caused many to wonder whether the Russian Energia launcher or Buran shuttle could be brought back into service. By then, however, all of the equipment for both (including the vehicles themselves) had fallen into disrepair or been repurposed after falling into disuse with the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, because of the imminent retirement of the American space shuttle by 2010 and the need for STS-type craft in the meantime to complete the International Space Station, some American and Russian scientists had been mulling over plans to possibly revive the already-existing Buran shuttles in the Buran program rather than spend money on an entirely new craft and wait for it to be fully developed[15][16] but the plans did not come to fruition. Recently there have been new interests in renewing the program temporarily while Russia struggles with the CSTS and Kliper design stages.[17][18]

Technical data

Mass breakdown

- Mass of Total Structure / Landing Systems: 42,000 kg

- Mass of Functional Systems and Propulsion: 33,000 kg

- SSME 14,200

- Maximum Payload: 30,000 kg

- Maximum liftoff weight: 105,000 kg

Dimensions

- Length: 36.37 m

- Wingspan: 23.92 m

- Height on Gear: 16.35 m

- Payload bay length: 18.55 m

- Payload bay diameter: 4.65 m

- Wing glove sweep: 78 degrees

- Wing sweep: 45 degrees

Propulsion

- Total orbital maneuvering engine thrust: 17,600 kgf

- Orbital Maneuvering Engine Specific Impulse: 362 sec

- Total Maneuvering Impulse: 5 kgf-sec

- Total Reaction Control System Thrust: 14,866 kgf

- Average RCS Specific Impulse: 275-295 sec

- Normal Maximum Propellant Load: 14,500 kg

Comparison to NASA Space Shuttle

Because Buran's debut followed that of Space Shuttle Columbia's, and because there were striking visual similarities between the two shuttle systems—a state of affairs which recalled the similarity between the Tupolev Tu-144 and Concorde supersonic airliners—many speculated that Cold War espionage played a role in the development of the Soviet shuttle. Despite remarkable external similarities, many key differences existed, which suggests that, had espionage been a factor in Buran's development, it would likely have been in the form of external photography or early airframe designs. One CIA commenter, however, states that Buran was based on a rejected NASA design.[19]

Key differences from the NASA Space Shuttle

- Buran was not an integral part of the system, but rather a payload for the Energia launcher. The orbiter had no main rocket engines, freeing space and weight for additional payload; the largest cylindrical structure is the Energia carrier-rocket, not just a fuel tank. In contrast, in the American Space Shuttle system, the three main engines on the rear of the orbiter comprise the second stage launch propulsion system, and the External Tank and twin boosters are not used to launch anything except an orbiter.[citation needed]

- The main engines were mounted on the core Energia stage and thus destroyed when it burns up in the atmosphere, unlike the U.S. Space Shuttle which has reusable main engines in the orbiter. Both designs feature reusable boosters (although reusability was not demonstrated on Energia). There were some plans for constructing a fully reusable Energia carrier, but funding cuts meant that this was never completed.[citation needed]

- The boosters used liquid propellant (kerosene/oxygen). The Space Shuttle's boosters use solid propellant.[20]

- Buran's equivalent of the shuttle's Orbital Maneuvering System used GOX/Kerosene propellant, with lower toxicity and higher performance (a specific impulse of 362 seconds)[citation needed] than the Shuttle's monomethyl hydrazine/nitrogen tetroxide OMS engines.

- Energia was designed from the start to be configured for a variety of uses, rather than just a shuttle launcher. Other payloads than Buran, with mass as high as 80 metric tons, could be lifted to space by Energia, as was the case on its first launch. The heaviest configuration (never built) would have been able to launch 200 tons into orbit. (The Shuttle-C concept was a similar proposal to the Energia system, envisaged to complement the space shuttle by adapting its boosters and external tank for use with other vehicles, but it never moved beyond the experimental mock-up stage. The NASA Ares V rocket, since canceled, was a similarly "shuttle-derived" idea.)[citation needed]

- The Energia launch rocket was also capable of delivering a payload to the Moon. However, this configuration was never tested. The Space Shuttle was never intended to go beyond Low Earth orbit.[citation needed]

- As Buran was designed to be capable of both manned and robotic flight, it had automated landing capability; the manned version was never operational. The Space Shuttle was later retrofitted with an automated landing capability; the equipment to make this possible was first flown on STS-121, but is intended only as a contingency, and was never used on any flight.[21]

- The orbiters were designed to carry two jet engines for increased return capability. Although they were not installed in the first orbiter for reason of weight limits on the first Energia launcher, provisions exist in the structure for later retrofit.[22] Although early designs of the NASA Space Shuttle also incorporated jet engines, the operation version landed as an unpowered glider, relying entirely on management of descent energy for landing.

- The nose landing gear is located much farther down the fuselage rather than just under the mid-deck as with the NASA Space Shuttle.

- Buran could lift 30 metric tons into orbit in its standard configuration, comparable to the early Space Shuttle's original 27.8 metric tons[23][24]

- Buran was designed to return 20 metric tons of payload from orbit, compared to 15 metric tons for the Space Shuttle orbiter.[citation needed]

- The drag chute was installed on Buran right from the start of the program as opposed to the Space Shuttle where the drag chute is added much later in the program.

- The lift-to-drag ratio of Buran is cited as 6.5,[25] compared to a subsonic L/D of 4.5 for the Space Shuttle.[26]

- The thermal protection tiles on the Buran and U.S. Space Shuttles are laid out differently. Soviet engineers believed their design to be thermodynamically superior.[24]

- Buran was designed to be moved to the launch pad horizontally on special train tracks, and then erected at the launch site. This enabled a much faster rollout than the US Space Shuttle, which is moved vertically, and as such must be moved very slowly (less than one mile per hour, typically taking about 6 hours to move the Mobile Launch Platform supporting the Shuttle stack from the VAB to the launch pad on a Crawler-Transporter.)[citation needed]

- The booster rockets were not constructed in segments vulnerable to leakage through O-rings, which caused the destruction of Challenger. (Their liquid-fueled nature would make this design inapplicable.) However, the liquid fuel for the booster rockets (see above) would have made them less easy to prepare - and hold ready - for flight than solid rocket fuel in the Shuttle boosters and in addition represented a potential explosive hazard on the ground.[citation needed]

- The manned version was intended to have a crew of ten as opposed to seven.[24]

See also

- Manned space missions

- Unmanned space missions

- Space exploration

- Space accidents and incidents

References

- ^ a b c Brian Harvey - The rebirth of the Russian space program: 50 years after Sputnik, new frontiers (2007) - Page 8 (Google Books link)

- ^ "Russian shuttle dream dashed by Soviet crash". YouTube. 2007-11-15. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TmbZ4-kgaak. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hendrickx, Bart; Bert Vis (2007-10-04). Energiya-Buran : The Soviet Space Shuttle. Praxis. pp. 526. ISBN 0387698485.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (November 20, 2008). "Buran - the Soviet 'space shuttle'". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7738489.stm. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ^ "Mir LII-1". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/mirlii1.htm. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ "Shuttle Buran". NASA. 12 November 1997. Archived from the original on 2006-08-04. http://web.archive.org/web/20060804153528/http://liftoff.msfc.nasa.gov/rsa/buran.html. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ Chertok, Boris Yevseyevich (2005). Asif A. Siddiqi. ed (PDF). Raketi i lyudi (trans. "Rockets and People"). NASA History Series. pp. 179. http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20050010181_2005010059.pdf. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- ^ "Экипажи "Бурана" Несбывшиеся планы.". buran.ru. http://www.buran.ru/htm/pilots.htm. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- ^ Wade, Mark. "Yeltsin cancels Buran project". Astronautix. http://www.astronautix.com/details/yelt5401.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-02.

- ^ "Mir-Shuttle Docking Module". Astronautix.com. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/mirodule.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Whitehouse, David (2002-05-13). "Russia's space dreams abandoned". bbc.co.uk (BBC). http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/1985631.stm. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ^ Energiya-Buran. ISBN 9780387698489. http://books.google.ca/books?id=VRb1yAGVWNsC.

- ^ "Energia Buran Where are they now". k26.com/buran/. http://www.k26.com/buran/Future/energia_-_buran_-_where_are_th.html. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- ^ http://www.buran-energia.com/blog/category/bourane/buran-OK-201/lang-pref/en/

- ^ Birch, Douglas (2003). "Russian space program is handed new responsibility" (url). Sun Foreign Staff. http://www.dailypress.com/sports/nationworld/bal-te.russia05feb05,0,3940646,full.story. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ "Russia ready to take lead on space station - Space- msnbc.com". MSNBC. 2005-06-10. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/8148275/page/3/. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "Soviet space shuttle could bail out NASA". Current.com. 2008-12-31. http://current.com/items/89670174/soviet_space_shuttle_could_bail_out_nasa.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "Soviet space shuttle could bail out NASA". Russiatoday.com. http://www.russiatoday.com/scitech/news/33330?gclid=CJSjwpD2qJgCFQEpGgod_jeUnA. Retrieved 2009-07-16.[dead link]

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/96unclass/farewell.htm#rft5

- ^ "Solid Rocket Boosters". Space Shuttle System. NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/returntoflight/system/system_SRB.html. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Shuttle to Carry Tools for Repair and Remote-Control Landing

- ^ "Buran Composition Turbojets". Buran-energia.com. 1988-11-15. http://www.buran-energia.com/bourane-buran/bourane-consti-reacteur.php. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Mark Wade, Encyclopedia Astronautica, "Shuttle," accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ a b c Aerospaceweb.org

- ^ NPO Molniya Buran page (accessed Sept. 20, 2010)

- ^ ,"[1]"'Space Shuttle Technical Conference pg 258'

External links

- Buran entry at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- Official website by the NPO "Molniya", makers of the Buran

- Detailed site on the Buran space shuttle

- Energia - all about the HLLV. Includes information about the Buran.

- Russian Aviation page

- Buran The Russian Shuttle - Gizmohighway Technology Guide

- German aviation museum acquires Buran test article for display (in German)

- Buran's first flight, lift-off video

- Aerospaceweb.org: Soviet Buran Space Shuttle

- 55°43′43″N 37°35′48″E / 55.728718°N 37.596803°E Gorky Park, with OK-TVA clearly visible

- 26°11′54″N 50°36′08″E / 26.198352°N 50.602121°E OK-GLI in Bahrain

- Buran Family overview

- RussianSpaceWeb.com

- Buran, The First Russian Shuttle at English Russia (photos, movie)

- The Soviet VKK (Vosdushno Kosmicheskiy Korabl) Space Shuttle Program

- Photo of collapsed Buran hangar

- Photo of Buran in collapsed hangar. The Buran's right front windshield is still visible under the debris.

Buran program Components Orbiters Launch site Testing Related topics Soviet and Russian government manned space programs Active Past Cancelled Space Shuttles  United States Space Shuttle program

United States Space Shuttle program Soviet Buran program

Soviet Buran program- Pathfinder (OV-098, ground tests)

- Enterprise (OV-101, atmospheric tests, retired)

- Columbia (OV-102, destroyed 2003)

- Challenger (OV-099, destroyed 1986)

- Discovery (OV-103, retired)

- Atlantis (OV-104, retired)

- Endeavour (OV-105, retired)

Myasishchev aircraft Civil Military Space Categories:- Myasishchev aircraft

- Manned spacecraft

- Partially reusable space launch vehicles

- Spaceplanes

- Shuttle Buran program

- Rocket-powered aircraft

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.