- Mobile device forensics

-

Forensic science

Physiological sciences Forensic anthropology

Forensic archaeology

Forensic dentistry

Forensic entomology

Forensic pathology

Forensic botanySocial sciences Forensic psychology

Forensic psychiatryForensic criminalistics Ballistics

Ballistic fingerprinting

Body identification

DNA profiling

Fingerprint analysis

Forensic accounting

Forensic arts

Forensic footwear evidence

Forensic toxicology

Questioned document examination

Vein matchingDigital forensics Computer forensics

Database forensics

Mobile device forensics

Network forensics

Forensic videoRelated disciplines Fire investigation

Detection of fire accelerants

Forensic engineering

Forensic linguistics

Forensic materials engineering

Forensic polymer engineering

Vehicular accident reconstructionPeople Auguste Ambroise Tardieu

Edmond Locard

William M. Bass

Juan VucetichRelated articles Crime scene

CSI effect

Perry Mason syndrome

Pollen calendar

Skid mark

Trace evidence

Use of DNA in forensic entomologyMobile device forensics is a branch of digital forensics relating to recovery of digital evidence or data from a mobile device under forensically sound conditions. The phrase mobile device usually refers to mobile phones; however, it can also relate to any digital device that has both internal memory and communication ability.

The use of phones in crime was widely recognised for some years, but the forensic study of mobile devices is a relatively new field, dating from the early 2000s. A proliferation of phones (particularly smartphones) on the consumer market caused a demand for forensic examination of the devices, which could not be met by existing computer forensics techniques.[1]

The memory type, custom interface and proprietary nature of mobile devices requires a different forensic process compared to computer forensics. Each device often has to have custom extraction techniques used on it. Mobile devices can be used to save several types of personal information such as contacts, photos, calendars and notes.

Contents

History

As a field of study forensic examination of mobile devices dates from the late 1990s and early 2000s. The role of mobile phones in crime had long been recognised by law enforcement. With the increased availability of such devices on the consumer market and the wider array of communication platforms they support (e.g. email, web browsing) demand for forensic examination grew.[1]

In comparison to computer forensics, law enforcement are much more likely to encounter a suspect with a mobile device in his possession and so the growth of demand for analysis of mobiles has increased exponentially in the last decade.

Early efforts to examine mobile devices used similar techniques to the first computer forensics investigations; analysing phone contents directly via the screen and photographing important content. Over time commercial tools appeared which allowed examiners to recover phone memory with minimal disruption and analyse it separately.[1]

In more recent years these commercial techniques have developed further and the recovery of deleted data from proprietary mobile devices has become possible with some specialist tools.

Types of evidence

As mobile device technology advances, the amount and types of data that can be found on a mobile device is constantly increasing. Evidence that can be potentially recovered by law enforcement agents from a mobile phone may come from several different sources, including SIM card, Handset and attached memory cards.

Traditionally mobile phone forensics has been associated with recovering SMS and MMS messaging, as well as call logs, contact lists and phone IMEI/ESN information. Newer generations of smart phones also include wider varieties of information; from web browsing, Wireless network settings, e-mail and other forms of rich internet media, including important data now retained on smartphone 'apps'.

Service provider logs

The European Union requires its members countries to retain certain telecommunications data for use in investigations. This includes data on calls made and retrieved. The location of a mobile phone can be determined and this geographical data must also be retained. Although this is a different science than forensic analysis which is undertaken once the mobile phone has been seized.

Forensic process

Main article: digital forensic processThe forensics process for mobile devices broadly matches other branches of digital forensics; however, some particular concerns apply. One of the main ongoing considerations for analysts is preventing the device from making a network/cellular connection; which may bring in new data, overwriting evidence. To prevent a connection mobile devices will often be transported and examined from within an Faraday cage (or bag).

Seizure

Seizing mobile devices is covered by the same legal considerations as other digital media. Mobiles will often be recovered switched on; as the aim of seizure is to preserve evidence the device will often be transported in the same state to avoid a shutdown changing files.[2]

Acquisition

The second step in the forensic process is acquisition, in this case usually referring to retrieval of material from a device (as compared to the bit-copy imaging used in computer forensics).[2]

Because of the proprietary nature of mobiles it is often not possible to acquire data with it powered down, most mobile device acquisition is performed live. With more advanced smartphones using advanced memory management, connecting it to a recharger and putting it into a faraday cage may not be good practice. The mobile device would recognize the network disconnection and therefore it would change its status information that can trigger the memory manager to write data.[3]

Most acquisition tools for mobile devices are commercial in nature and consist of a hardware and software component, often automated.

Examination and analysis

As an increasing number of mobile devices use high-level file systems, similar to the file systems of computers, methods and tools can be taken over from hard disk forensics or only need slight changes.[4]

The FAT file system is generally used on NAND memory.[5] A difference is the block size used, which is larger than 512 bytes for hard disks and depends on the used memory type, e.g., NOR type 64, 128, 256 and NAND memory 16, 128, 256, or 512 kilobyte.

Different software tools can extract the data from the memory image. One could use specialized and automated forensic software products or generic file viewers such as any hex editor to search for characteristics of file headers. The advantage of the hex editor is the deeper insight into the memory management, but working with a hex editor means a lot of handwork and file system as well as file header knowledge. In contrast, specialized forensic software simplifies the search and extracts the data but may not find everything. AccessData, Sleuthkit, and EnCase, to mention only some, are forensic software products to analyze memory images.[6] Since there is no tool that extracts all possible information, it is advisable to use two or more tools for examination. There is currently (February 2010) no software solution to get all evidences from flash memories.[7]

Data acquisition types

Physical acquisition

Physical acquisition implies a bit-by-bit copy of an entire physical store (e.g., a memory chip). A physical acquisition has the advantage of allowing deleted files and data remnants to be examined. Physical extraction acquires information from the device by direct access to the flash memories. Generally this is harder to achieve because the device vendors needs to secure against arbitrary reading of memory so that a device may be locked to a certain operator. A physical extraction is the method most similar to the examination of a personal computer. It produces a bit-by-bit copy of the device's flash memory. Generally the physical extraction is then split into two steps, the dumping phase and the decoding phase.

Logical acquisition

Logical acquisition implies a bit-by-bit copy of logical storage objects (e.g., directories and files) that reside on a logical store (e.g., a file system partition). Logical acquisition has the advantage that system data structures are easier for a tool to extract and organize. Logical extraction acquires information from the device using the vendor interface for synchronizing the contents of the phone with a personal computer. This usually does not produce any deleted information, due to it normally being removed from the file system of the phone. However, in some cases the phone may keep a database file of information which does not overwrite the information but simply marks it as deleted and available for later overwriting. In this case, if the device allows file system access through their synchronization interface, it is possible to recover deleted information. A logical extraction is generally easier to work with as it does not produce a large binary blob. However a skilled forensic examiner will be able to extract far more information from a physical extraction.

Manual acquisition

The user interface can be utilized to investigate the content of the memory. Therefore the device is used as normal and pictures are taken from the screen. This method has the advantage that the operating system makes the transformation of raw data into human interpretable information. In practice this method is applied to cell phones, e.g., Project-a-Phone, PDAs and navigation systems.[8] The disadvantage is that only data visible to the operating system can be recovered and that all data are only available in form of pictures.

External memory

External memory devices are SIM cards, SD cards, MMC cards, CF cards, and the Memory Stick. For external memory and the USB flash drive, appropriate software, e.g., the Unix command dd, is needed to make the bit-level copy. Furthermore USB flash drives with memory protection do not need special hardware and can be connected to any computer. Many USB drives and memory cards have a write-lock switch that can be used to prevent data changes, while making a copy. If the USB drive has no protection switch a write blocker can be used to mount the drive in a read-only mode or, in an exceptional case, the memory chip can be desoldered. The SIM and memory cards need a card reader to make the copy. The SIM card is soundly analyzed, such that it is possible to recover (deleted) data like contacts or text messages.[3]

Internal memory

This section describes various possibilities to save the internal storage, nowadays mostly flash memory.

System commands

Mobile devices do not provide the possibility to run or boot from a CD, connecting to a network share or another device with clean tools. Therefore system commands could be the only way to save the volatile memory of a mobile device. With the risk of modified system commands it must be estimated if the volatile memory is really important. A similar problem arises when no network connection is available and no secondary memory can be connected to a mobile device because the volatile memory image must be saved on the internal non-volatile memory, where the user data is stored and most likely deleted important data will be lost. System commands are the cheapest method, but imply some risks of data loss. Every command usage with options and output must be documented.

AT commands

AT commands are old modem commands, e.g., Hayes command set and Motorola phone AT commands, and can therefore only be used on a device that has modem support. Using these commands one can only obtain information through the operating system, such that no deleted data can be extracted.[3]

Flasher tools

A flasher tool is a programming hardware and/or software that can be used to program (flash) the device memory, e.g., EEPROM or flash memory. These tools mainly originate from the manufacturer or service centers for debugging, repair, or upgrade services. They can overwrite the non-volatile memory and some, depending on the manufacturer or device, can also read the memory to make a copy, originally intended as a backup. The memory can be protected from reading, e.g., by software command or destruction of fuses in the read circuit.[9] Note, this would not prevent writing or using the memory internally by the CPU. The flasher tools are easy to connect and use, but some can change the data and have other dangerous options or do not make a complete copy [4]

JTAG

Existing standardized interfaces for reading data are built into several mobile devices, e.g., to get position data from GPS equipment (NMEA) or to get deceleration information from airbag units.[8]

Not all mobile devices provide such a standardized interface nor does there exist a standard interface for all mobile devices, but all manufacturers have one problem in common. The miniaturizing of device parts opens the question how to test automatically the functionality and quality of the soldered integrated components. For this problem an industry group, the Joint Test Action Group (JTAG), developed a test technology called boundary scan.

Despite the standardization there are four tasks before the JTAG device interface can be used to recover the memory. To find the correct bits in the boundary scan register one must know which processor and memory circuits are used and how they are connected to the system bus. When not accessible from outside one must find the test points for the JTAG interface on the printed circuit board and determine which test point is used for which signal. The JTAG port is not always soldered with connectors, such that it is sometimes necessary to open the device and re-solder the access port.[4] The protocol for reading the memory must be known and finally the correct voltage must be determined to prevent damage to the circuit.[3]

The boundary scan produces a complete forensic image of the volatile and non-volatile memory. The risk of data change is minimized and the memory chip must not be desoldered. Generating the image can be slow and not all mobile devices are JTAG enabled. Also, it can be difficult to find the test access port.[5]

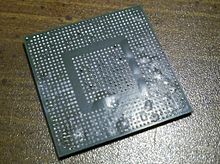

Forensic desoldering

Commonly referred to as a "Chip-Off" technique within the industry - this is the last and most intrusive method to get a memory image is to desolder the non-volatile memory chip and connect it to a memory chip reader. This method contains the potential danger of total data destruction: it is possible to destroy the chip and its content because of the heat required during desoldering. Before the invention of the BGA technology it was possible to attach probes to the pins of the memory chip and to recover the memory through these probes. The BGA technique bonds the chips directly onto the PCB through molten solder balls, such that it is no longer possible to attach probes.

Desoldering the chips is done carefully and slowly, so that the heat does not destroy the chip or data. Before the chip is desoldered the PCB is baked in an oven to eliminate remaining water. This prevents the so-called popcorn effect, at which the remaining water would blow the chip package at desoldering.

There are mainly three methods to melt the solder: hot air, infrared light, and steam-phasing. The infrared light technology works with a focused infrared light beam onto a specific integrated circuit and is used for small chips. The hot air and steam methods cannot focus as much as the infrared technique.

Chip re-balling

After desoldering the chip a re-balling process cleans the chip and adds new tin balls to the chip. Re-balling can be done in two different ways.

- The first is to use a stencil. The stencil is chip-dependent and must fit exactly. Then the tin-solder is put on the stencil. After cooling the tin the stencil is removed and if necessary a second cleaning step is done.

- The second method is laser re-balling; see.[10][11][12] Here the stencil is programmed into the re-balling unit. A bondhead (looks like a tube/needle) is automatically loaded with one tin ball from a solder ball singulation tank. The ball is then heated by a laser, such that the tin-solder ball becomes fluid and flows onto the cleaned chip. Instantly after melting the ball the laser turns off and a new ball falls into the bondhead. While reloading the bondhead of the re-balling unit changes the position to the next pin.

A third method makes the entire re-balling process unnecessary. The chip is connected to an adapter with Y-shaped springs or spring-loaded pogo pins. The Y-shaped springs need to have a ball onto the pin to establish an electric connection, but the pogo pins can be used directly on the pads on the chip without the balls.[3][4]

The advantage of forensic desoldering is that the device does not need to be functional and that a copy without any changes to the original data can be made. The disadvantage is that the re-balling devices are expensive, so this process is very costly and there are some risks of total data loss. Hence, forensic desoldering should only be done by experienced laboratories.[5]

Tools

Main article: List of digital forensics tools#Mobile device forensicsEarly investigations consisted of live analysis of mobile devices; with examiners photographing or writing down useful material for use as evidence. This had the disadvantage of risking the modification of the device content, as well as leaving many parts of the proprietary operating system inaccessible.

In recent years a number of hardware/software tools have emerged to recover evidence from mobile devices. Most tools consist of a hardware portion, with a number of cables to connect the phone to the acquisition machine, and some software, to extract the evidence and, occasionally, to analyse it.

Some current tools include those by Radio Tactics, eDEC Digital Forensics, Cellebrite UFED, Micro Systemation XRY, Oxygen Forensic Suite 2, Paraben Device Seizure and MOBILedit! Forensic.[13]

An example of a mobile forensics tool currently available to forensic investigators:

Controversies

In general there exists no standard for what constitutes a supported device in a specific product. This has led to the situation where different vendors define a supported device differently. A situation such as this makes it much harder to compare products based on vendor provided lists of supported devices. For instance a device where logical extraction using one product only produces a list of calls made by the device may be listed as supported by that vendor while another vendor can produce much more information. Furthermore different products extract different amounts of information from different devices. This leads to a very complex landscape when trying to overview the products. In general this leads to a situation where testing a product extensively before purchase is strongly recommended. It is quite common to use at least two products which complement each other.

For a detailed discussion see Gubian and Savoldi, 2007. For a wide overview on nand flash forensic see Salvatore Fiorillo, 2009[7]

Anti-forensics

Anti-computer forensics is more difficult because of the small size of the devices and the user's restricted data accessibility.[5] Nevertheless there are developments to secure the memory in hardware with security circuits in the CPU and memory chip, such that the memory chip cannot be read even after desoldering.[14][15]

References

- ^ a b c Casey, Eoghan (2004). Digital Evidence and Computer Crime, Second Edition. Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-163104-4.

- ^ a b Wayne, Jansen., & Ayers, Rick. (May 2007). Guidelines on cell phone forensics. retrieved from http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-101/SP800-101.pdf

- ^ a b c d e Svein Y. Willassen. (2006) Retrieved from Forensic analysis of mobile phone internal memory.

- ^ a b c d Marcel Breeuwsma, Martien de Jongh, Coert Klaver, Ronald van der Knijff, and Mark Roeloffs. (2007). retrieved from Forensic Data Recovery from Flash Memory. Small l Scale Digital Device Forensics Journal, Volume 1 (Number 1).

- ^ a b c d Ronald van der Knijff. (2007). retrieved from 10 Good Reasons Why You Should Shift Focus to Small Scale Digital Device Forensics.

- ^ Rick Ayers, Wayne Jansen, Nicolas Cilleros, and Ronan Daniellou. (October 2005). Retrieved from Cell Phone Forensic Tools: An Overview and Analysis. National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- ^ a b Salvatore Fiorillo. (December 2009). retrieved from Theory and practice of flash memory mobile forensics. Theosecurity.com.

- ^ a b Eoghan Casey. Handbook of computer crime investigation - forensic tools and technology. Academic Press, 2. edition, 2003.

- ^ Tom Salt and Rodney Drake. US Patent 5469557. (1995). Retrieved from Code protection in microcontroller with EEPROM fuses.

- ^ Homepage of Factronix

- ^ Video: Scheme of the Laser Re-balling process

- ^ Video: Re-balling process

- ^ Kipper, Greg. Wireless Crime and Forensic Investigation. Auerbach Publications, 2007, p. 97.

- ^ Secure Boot Patent

- ^ Harini Sundaresan. (July 2003). Retrieved from OMAP platform security features, Texas Instruments.

External links

- Video Tutorial on iPhone 4 Forensics

- Seminar 'Covert Channels and Embedded Forensics'

- Conference 'Mobile Forensics World'

- 'Theory and practice of flash memory mobile forensics'

- SG Punja; RP Mislan. "Mobile Device Analysis". Small Scale Digital Device Forensics Journal. http://www.ssddfj.org/papers/SSDDFJ_V2_1_Punja_Mislan.pdf. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

Branches Computer forensics • Mobile device forensics • Network forensics • Database forensics • Windows To GoHardware Software EnCase • FTK • PTK Forensics • The Sleuth Kit • The Coroner's Toolkit • COFEE • Selective file dumper • HashKeeperCertification Processes / Topics Organisations National Software Reference Library • American Society of Digital Forensics & eDiscovery • HTCIA • Department of Defense Cyber Crime Center • NHTCU • AHTCCPeople Eoghan Casey • Clifford Stoll • Erik LaykinCategories:- Computer security procedures

- Digital forensics

- Information technology audit

- Mobile computers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.