- Mjölnir

-

"Thor's Hammer" redirects here. For other uses, see Thor's Hammer (disambiguation).For other uses, see Mjolnir (disambiguation).

Drawing of a 4.6 cm gold-plated silver Mjölnir pendant found at Bredsätra in Öland, Sweden. The original is housed at the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities.

Drawing of a 4.6 cm gold-plated silver Mjölnir pendant found at Bredsätra in Öland, Sweden. The original is housed at the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities.

In Norse mythology, Mjölnir (

/ˈmjɒlnɪər/ or /ˈmjɒlnər/ myol-n(ee)r; also Mjǫlnir, Mjollnir, Mjölner or Mjølner) is the hammer of Thor, a major god associated with thunder in Norse mythology. Distinctively shaped, Mjölnir is depicted in Norse mythology as one of the most fearsome weapons, capable of leveling mountains. Though generally recognized and depicted as a hammer, Mjölnir is sometimes referred to as an axe or club.[1] In the 13th century Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson relates that the Svartálfar Sindri, the brother of Brokkr, made Mjöllnir while in a contest with Loki to see who could make the most wonderful and useful items for the Gods and Goddesses in Asgard

/ˈmjɒlnɪər/ or /ˈmjɒlnər/ myol-n(ee)r; also Mjǫlnir, Mjollnir, Mjölner or Mjølner) is the hammer of Thor, a major god associated with thunder in Norse mythology. Distinctively shaped, Mjölnir is depicted in Norse mythology as one of the most fearsome weapons, capable of leveling mountains. Though generally recognized and depicted as a hammer, Mjölnir is sometimes referred to as an axe or club.[1] In the 13th century Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson relates that the Svartálfar Sindri, the brother of Brokkr, made Mjöllnir while in a contest with Loki to see who could make the most wonderful and useful items for the Gods and Goddesses in AsgardThe Prose Edda gives a summary of Mjölnir's special qualities in that, with Mjölnir, Thor:

... would be able to strike as firmly as he wanted, whatever his aim, and the hammer would never fail, and if he threw it at something, it would never miss and never fly so far from his hand that it would not find its way back, and when he wanted, it would be so small that it could be carried inside his tunic.[1]

Contents

Etymology

Mjölnir simply means "crusher", referring to its pulverizing effect. Mjölnir might be related to the Russian word молния (molniya) and the Welsh word mellt (both words being translated as "lightning"). This second theory parallels with the idea that Thor, being a god of thunder, therefore might have used lightning as his weapon.[2] It is related to words such as the Icelandic verbs mölva ("to crush") and mala ("to grind"), and Swedish noun mjöl ("flour"), all related to English meal, mill, and miller. Similar words, all stemming from the Proto-Indo-European root *melə, can be found in almost all European languages, e.g. the Slavic melevo ("grain to be ground") and molot ("hammer"), the Russian Молот (molot—"hammer"), the Greek μύλος (mylos—"mill"), the Spanish moler ("to grind"), and the Latin malleus "hammer", from which English mallet derives, as well as the Latin mola ("mill").

Attestations

Prose Edda

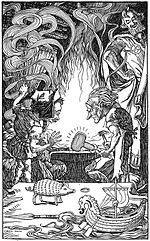

The most popular version of the creation of Mjölnir myth, found in Skáldskaparmál from Snorri's Edda,[3] is as follows. In one story Loki sends up to the dwarves called the Sons of Ivaldi that create precious items for the gods: Odin's spear Gungnir, and Freyr's foldable boat Skíðblaðnir. Then Loki bets his head that the two Dwarves, Sindri (or Eitri) and his brother Brokkr would never succeed in making items more beautiful than those of Ivaldi's sons. The bet is accepted and the two brothers begin working. Thus Eitri puts a pig's skin in the forge and tells his brother (Brokkr) never to stop blowing until he comes and takes out what he put in.

Loki, in disguise as a fly, comes and bites Brokkr on the arm but he continues to blow. Then Eitri takes out Gullinbursti which is Freyr's boar with shining bristles. Then Eitri puts some gold in the furnace and gives Brokkr the same order. Loki in the fly guise comes again and bites Brokkr's neck twice as hard. But as before nothing happens and Eitri takes out Draupnir, Odin's ring, having duplicates falling from itself every ninth night.

Drawing of hammer depicted on runic inscription Sö 86 located in Åby, Uppland, Sweden.

Drawing of hammer depicted on runic inscription Sö 86 located in Åby, Uppland, Sweden.

Eitri then puts iron in the forge and tells Brokkr to never stop blowing. Loki comes again and bites Brokkr on the eyelid much harder than before and the blood makes him stop blowing for a short while. When Eitri comes and takes out Mjöllnir, the handle is a bit short (making it one handed). Eitri and Brokkr win the bet, which was Loki's head. However, the bet cannot be honoured, since they need to cut the neck as well, which was not part of the deal. As a result, Brokkr sews Loki's mouth to teach him a lesson.

Poetic Edda

Thor possessed a formidable chariot, which is drawn by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. A belt, Megingjörð, and iron gloves, Járngreipr, were used to lift Mjölnir. Mjölnir is the focal point of some of Thor's adventures.

This is clearly illustrated in a poem found in the Poetic Edda titled Þrymskviða. The myth relates that the giant, Þrymr, steals Mjölnir from Thor and then demands the goddess Freyja in exchange. Loki, the god notorious for his duplicity, conspires with the other Æsir to recover Mjölnir by disguising Thor as Freyja and presenting him as the "goddess" to Þrymr.

At a banquet Þrymr holds in honor of the impending union, Þrymr takes the bait. Unable to contain his passion for his new maiden with long, blond locks (and broad shoulders), as Þrymr approaches the bride by placing Mjölnir on "her" lap, Thor rips off his disguise and destroys Þrymr and his giant cohorts.

Archaeological record

Emblemic pendants

Myths, artifacts, and institutions revolving around Thor indicate his prominent place in the mind of medieval Scandinavians. His following ranged in influence, but the Viking warrior aristocracy were particularly inspired by Thor's ferocity in battle. In the medieval legal arena, according to Joseph Campbell, "And at the Icelandic Things (court assemblies) the god invoked in testimony of oaths, as 'the Almighty God,' was Thor."[4]

Emblematic of their devotion were the appearance of miniature replicas of Mjöllnir, widely popular in Scandinavia.

Many of these replicas were also found in graves and tended to be furnished with a loop, allowing them to be worn. Mjölnir amulets were most widely discovered in areas with a strong Christian influence including southern Norway, south-eastern Sweden, and Denmark.[5] Due to the similarity of equal-armed, square crosses featuring figures of Christ on them at around the same time, the wearing of Thor's hammers as pendants may have come into fashion in defiance of the square amulets worn by newly converted Christians in the regions.[6]

The shape taken by these pendants varied by region. The Icelandic variant was cross-shaped, while Swedish and Norwegian variants tended to be arrow or T-shaped. About 50 specimens of such hammers were found widely dispersed throughout Scandinavia, dating from the 9th to 11th centuries. A few such examples were also found in England. An iron Thor's hammer pendant excavated in Yorkshire, dating to ca. AD 1000 bears an unical inscription preceded and followed by a cross, interpreted as indicating a Christian owner syncretizing pagan and Christian symbolism.[7] A 10th century soapstone mold found at Trendgården, Jutland, Denmark is notable for allowing the casting of both crucifix and Thor's hammer pendants.[8] A silver specimen found near Fossi, Iceland (now in the National Museum of Iceland) can be interpreted as either a Christian cross or a Thor's hammer. Unusually, the elongated limb of the cross ends in a beast's (perhaps a wolf's) head.

A precedent of these Viking Age Thor's hammer amulets are recorded for the migration period Alemanni, who took to wearing Roman "Hercules' Clubs" as symbols of Donar.[9] A possible remnant of these Donar amulets was recorded in 1897, as a custom of Unterinn (South Tyrolian Alps) of incising a T-shape above front doors for protection against evils of all kinds, especially storms.[10]

Stones

The Stenkvista runestone in Södermanland, Sweden, shows Thor's hammer instead of a cross.

The Stenkvista runestone in Södermanland, Sweden, shows Thor's hammer instead of a cross.

Some image stones and runestones found in Denmark and southern Sweden bear an inscription of a hammer. Runestones depicting Thor's hammer include runestones U 1161 in Altuna, Sö 86 in Åby, Sö 111 in Stenkvista, Sö 140 in Jursta, Vg 113 in Lärkegapet, Öl 1 in Karlevi, DR 26 in Laeborg, DR 48 in Hanning, DR 120 in Spentrup, and DR 331 in Gårdstånga.[11][12] Other runestones included an inscription calling for Thor to safeguard the stone. For example, the stone of Virring in Denmark had the inscription þur uiki þisi kuml, which translates into English as "May Thor hallow this memorial." There are several examples of a similar inscription, each one asking for Thor to "hallow" or protect the specific artifact. Such inscriptions may have been in response to the Christians, who would ask for God's protection over their dead.[13]

Swastika symbol

Further information: Thurmuth swordAccording to some scholars, the swastika shape may have been a variant popular in Anglo-Saxon England prior to Christianization, especially in East Anglia and Kent.[14] Wilson (1894) points out that while the swastika had been "vulgarly called in Scandinavia the hammer of Thor", the symbol properly so called had a Y or T shape.[15]

Modern usage

The coat of arms of the Torsås Municipality, Sweden features a depiction of Mjöllnir.

The coat of arms of the Torsås Municipality, Sweden features a depiction of Mjöllnir.

Many practitioners of Germanic Neopagan faiths wear Mjöllnir pendants as a symbol of that faith worldwide. Renditions of Mjöllnir are designed, crafted and sold by some Germanic Neopagan groups and individuals.[16] Some controversy has occurred concerning the potential recognition of the symbol as a religious symbol by the United States government.[17]

Outside of Germanic Neopaganism, depictions of Mjöllnir are used in Scandinavian logos and iconography, such as the Mjöllnir logo of the Bornholm Museum in Denmark and the coat of arms for Torsås Municipality, Sweden. Mjöllnir pendants are popular in general in Scandinavia and can be seen elsewhere in heavy metal (especially Black metal and Viking metal) and "Dark" subcultures, and, to a lesser extent, among Rockers and biker subcultures. Also Mjolnir is the name of the armor that Master Chief wears in the Halo series.

See also

- Battle Axe culture

- Bracteate

- Donar's oak

- Hercules' Club (amulet)

- Axe of Perun

- Ukonvasara

- Irminsul

- Labrys

- Vajra

- List of mythological objects

- Sun cross

- Mjolnir (Marvel Comics)

Notes

- ^ a b Orchard (2002:255).

- ^ Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964. p81

- ^ Snorri's Edda, Skaldskaparmal. p. 41.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (1986), Occidental Mythology, Vol. 3 of 4 of the series The Masks of God, Penguin (publisher), 1986, later printing. Vol. 3 first issued 1965.

- ^ Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964. p. 83

- ^ Ellis Davidson, H.R. (1965). Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe, p. 81, ISBN 0140136274

- ^ [1]Schoyen Collection, MS 1708

- ^ This has been interpreted as the property of a craftsman "hedging his bets" by catering to both a Christian and a pagan clientele.[2][3]

- ^ Werner: Herkuleskeule und Donar-Amulett. in: Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz Nr. 11, Mainz 1966

- ^ Joh. Adolf Heyl, Volkssagen, Bräuche und Meinungen aus Tirol (Brixen: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Kath.-polit. Pressvereins, 1897), p. 804.

- ^ Holtgård, Anders (1998). "Runeninschriften und Runendenkmäler als Quellen der Religionsgeschichte". In Düwel, Klaus; Nowak, Sean. Runeninschriften als Quellen Interdisziplinärer Forschung: Abhandlungen des Vierten Internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4–9 August 1995. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 727. ISBN 3-11-015455-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=KYqsisEVQHEC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ McKinnell, John; Simek, Rudolf; Düwel, Klaus (2004). "Gods and Mythological Beings in the Younger Futhark". Runes, Magic and Religion: A Sourcebook. Vienna: Fassbaender. pp. 116–133. ISBN 3-900538-81-6. http://dro.dur.ac.uk/1053/1/1053.pdf.

- ^ Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964. p. 82–83.

- ^ Mayr-Harting, Henry, The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England (1991), p. 3: "Many cremation pots of the early Anglo-Saxons have the swastika sign marked on them, and in some the swastikas seems to be confronted with serpents or dragons in a decorative design. This is a clear reference to the greatest of all Thor's struggles, that with the World Serpent which lay coiled round the earth." Christopher R. Fee , David Adams Leeming, Gods, Heroes, and Kings: The Battle for Mythic Britain (2001), p. 31: "The image of Thor's weapon spinning end-over-end through the heavens is captured in art as a swastika symbol (common in Indo-European art, and indeed beyond); this symbol is—as one might expect—widespread in Scandinavia, but it also is common on Anglo-Saxon grave goods of the pagan period, notably in East Anglia and Kent."

- ^ Thomas Wilson (1894)[4], citing Waring, Ceramic Art in Remote Ages, p. 12.

- ^ Examples include "Wodanesdag" in Canada and "Hammers By Weylandsdöttir" in the United States.

- ^ Hudson Jr., David L.Va. inmate can challenge denial of Thor's Hammer June 6, 2007 at the firstamendmentcenter.org website.

References

- Orchard, Andy (2002). Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell.

- Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964.

External links

Norse paganism Deities,

heroes,

and figuresOthersAsk and Embla · Dís (Norns · Valkyries) · Dwarf · Einherjar · Elves (Light elves · Dark elves) · Fenrir · Hel · Jörmungandr · Jötunn · Sigurd · Völundr · Vættir

Locations Asgard · Bifröst · Fólkvangr · Ginnungagap · Hel · Jötunheimr · Midgard · Múspellsheimr · Niflheim · Valhalla · Vígríðr · Wells (Mímisbrunnr · Hvergelmir · Urðarbrunnr) · YggdrasilEvents Sources Society See also Categories:- Archaeological artefact types

- Artifacts in Norse mythology

- Thor

- Germanic paganism

- Hammers

- Mythological weapons

- Religious symbols

- Viking Age

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.