- Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting

-

Left image: A "Bellini type" Islamic prayer rug, seen from the top, at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in Gentile Bellini's Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century.

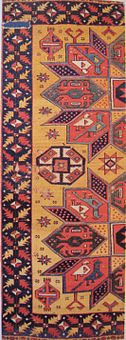

Right image: Prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century, with "re-entrant" keyhole motif.Carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from the Ottoman Empire, Armenia, Azerbaijan, the Levant or the Mamluk state of Egypt or Northern Africa, were used as important decorative features in paintings from the 14th century onwards. More depictions of Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting survive than actual carpets produced before the 17th century, so the study of these paintings is important for constructing the history of carpetmaking itself. Such carpets were often integrated into Christian imagery as symbols of luxury and status of Middle-Eastern origin, and together with Pseudo-Kufic script offer an interesting example of the integration of Eastern elements into Renaissance painting and of Islamic influences on Christian art.

Contents

Characteristics

First Oriental carpet (and first animal carpet) in a European painting, Fra Bartolomeo Annunciation, 1252.

First Oriental carpet (and first animal carpet) in a European painting, Fra Bartolomeo Annunciation, 1252. Left image: Domenico di Bartolo's The Marriage of the Foundlings features a large carpet with a Chinese-inspired phoenix-and-dragon pattern, 1440.[1]

Left image: Domenico di Bartolo's The Marriage of the Foundlings features a large carpet with a Chinese-inspired phoenix-and-dragon pattern, 1440.[1]

Right image: Phoenix-and-dragon carpet, first half or middle of the 15th century.[1]Pile carpets with geometric design are known to have been produced from the 13th century among the Seljuks of Rum in eastern Anatolia, whom Venice had had commercial relations since 1220.[2] The Medieval trader and traveler Marco Polo himself mentioned that the carpets produced at Konya were the best in the world.[2] Carpets were also produced in Islamic Spain, and one is shown in a fresco of the 1340s in the Palais des Papes, Avignon.[3] The vast majority of carpets in 15th and 16th century paintings are either from the Ottoman Empire, or possibly European copies of these types from the Balkans, Spain, or elsewhere. In fact these were not the finest Islamic carpets of the period, and few of the top-quality Turkish "court" carpets are seen. Even finer than these, Persian carpets do not appear until the end of the 16th century, but become increasingly popular among the very wealthy in the 17th century. The very refined Mamluk carpets from Egypt are occasionally seen, mostly in Venetian paintings.[4]

One of the first uses of an oriental carpet in a European painting is Simone Martini's Saint Louis of Toulouse Crowning Robert of Anjou, King of Naples, painted in 1316-1319.[5] Most European depictions of Oriental carpets were extremely faithful to the originals, judging by comparison with the few surviving examples of actual rugs of contemporary date. Their larger scale also allows more detailed and accurate depictions than those shown in miniature paintings from Turkey or Persia. Most carpets use Islamic geometric designs, with the earliest ones also using animal patterns such as the originally Chinese-inspired "phoenix-and-dragon", as in Domenico di Bartolo's Marriage of the Foundlings (1440). These had been stylised and simplified into near-geometric motifs in their transmission to the Islamic world.[6]The whole group, referred to in the literature as "Dragon" carpets, was apparently made by Armenians in Eastern Asia Minor or in the Caucasus.[7] They have disappeared from paintings by about the end of the 15th century. Only a handful of original animal-pattern carpets survive, mostly also from European churches, where their rarity presumably preserved them.[8]

Display of a "small-pattern Holbein" Oriental carpet in Andrea Previtali's The Annunciation, ca. 1508.[9]

Display of a "small-pattern Holbein" Oriental carpet in Andrea Previtali's The Annunciation, ca. 1508.[9]

Although the carpets were displayed on a public floor in a few examples, most carpets on the floor are in an area reserved for the main protagonists, very often on a dais or in front of an altar, or down steps in front of the Virgin Mary or Saints, or rulers,[10] in the manner of a modern red carpet. This presumably reflected the contemporary practice of royalty; in Denmark the 16th century Persian Coronation Carpet is used under the throne for coronations to this day. They are also often hung over balustrades or out of windows for festive occasions, such as the processions through Venice shown by Vittore Carpaccio or Gentile Bellini (see gallery);[11] when Carpaccio's St Ursula embarks they are hung over the sides of boats and footbridges.[12]

The Virgin Mary in Andrea Mantegna's San Zeno Altarpiece combines pseudo-Arabic halos and garment hems, with an Oriental carpet at her feet (1456-1459).

The Virgin Mary in Andrea Mantegna's San Zeno Altarpiece combines pseudo-Arabic halos and garment hems, with an Oriental carpet at her feet (1456-1459).

Oriental carpets were used extremely often as a decorative element in religious scenes, and were a symbol of luxury, status and taste,[13] although they were becoming more widely available throughout the period, which is reflected in the paintings. In some cases, such as paintings by Gentile Bellini, the carpets reflect an early Orientalist interest, but for most painters they merely reflect the prestige of the carpets in Europe. A typical example is the Turkish carpet at the feet of the Virgin Mary in the 1456-1459 San Zeno Altarpiece by Andrea Mantegna (see detail).[14] Non-royal portrait sitters were more likely to place their carpet on a table or other piece of furniture, especially in Northern Europe, though small rugs beside a bed are not uncommon, as in the Arnolfini Portrait of 1434.[15] Carpets are seen on tables in particular in Italian scenes showing the Calling of Matthew, when he was engaged in his work as a tax-collector,[16] and the life of Saint Eligius, who was a goldsmith. Both are shown sitting doing business at a carpet-covered table or shop counter.

The Oriental carpets used in Renaissance painting had various geographical origins, designated in contemporary Italy by different names: the cagiarini (Mamluk design from Egypt), the damaschini (Damascus region), the barbareschi (North Africa), the rhodioti (probably imported through Rome), the turcheschi (Ottoman Empire) and the simiscasa (Circassian or Caucasian).[17]

Some of the prayer carpets represented in Christian religious paintings are also Islamic prayer mats, with such motifs as the mihrab or the Kaaba (the so-called re-entrant carpets, later called the "Bellini" type).[18] The representation of such prayer rugs disppeared after 1555, probably as a consequence of the realization of their religious meaning and connection to Islam.[19]

The depiction of Oriental carpets in paintings other than portraits generally declined after the 1540s, corresponding to a decline in the taste for highly detailed representation of objects (Detailism) among painters,[20] and grander classicising surrounds for hieratic religious images.

Carpet patterns named after artists

Painting by Lorenzo Lotto, 1505, with a "Bellini" pattern.

Painting by Lorenzo Lotto, 1505, with a "Bellini" pattern.

When Western scholars explored the history of Islamic carpetmaking, several types of carpet pattern became conventionally called after the names of European painters who had used them, and these terms remain in use. The classification is mostly that of Kurt Erdmann, once Director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst (Berlin), and the leading carpet scholar of his day. Some of these types ceased to be produced several centuries ago, and the location of their production remains uncertain, so obvious alternative terms were not available. The classification ignores the border patterns, and distinguishes between the type, size and arrangement of gul, or larger motifs in the central field of the carpet. In addition to four types of Holbein carpets,[21] there are Bellini carpets, Crivellis, Memlings, and Lotto carpets.[22]

Bellini carpets

Left image: Lorenzo Lotto's Husband and Wife, 1523, with a "Bellini" carpet showing the keyhole re-entrant motif.

Right image: Re-entrant prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century.Both Giovanni Bellini and his brother Gentile (who visited Istanbul in 1479) painted examples of these prayer-rugs with a single "re-entrant" or keyhole motif at the bottom of a larger figure traced in a thin border. At the top end the borders close diagonally to a point, from which hangs down a "lamp". The design had Islamic significance, and its function seems to have been recognised in Europe, as they were known in English as "musket" carpets, a corruption of "mosque".[23] In the Gentile Bellini seen at top the rug is the "right" way round; often this is not the case. Later Ushak prayer-rugs where both ends have the diagonal pointed inner border, as at the top only of Bellini rugs, are sometimes known as Tintoretto rugs, though this term is not as commonly used as the others mentioned here.[24]

Crivelli carpets

Left image: Carlo Crivelli's Annunciation with St Emidius, 1486, with Crivelli carpet in the upper left corner. See enlarged detail at left. Note that there is a second, different carpet at top center.

Right image: "Crivelli" carpet, Anatolia, late 15th-early 16th century.Carlo Crivelli twice painted what seems to be the same small rug, with the centre taken up with a complex sixteen-pointed star motif made up of several compartments in different colours, some containing highly stylised animal motifs. Comparable actual carpets are extremely rare, but there are two in Budapest.[25] The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius in the National Gallery, London (1486) shows the type hung over a balcony to the top left. These seem to be a transitional type between the early animal-pattern carpets and later purely geometrical designs, such as the Holbein types, perhaps reflecting increased Ottoman enforcement of Islamic aniconism.[26]

-

Carlo Crivelli's Virgin Mary Annunciate (detail), 1482.

Memling carpets

Left image: yellow Oriental carpet in Hans Memling altarpiece of 1488-1490. The "hooked" motif defines a "Memling carpet".[27] Louvre Museum.

Right image: Konya 18th century carpet with Memling gul design. Carpet detail, Flemish school, 16th century, Petit Palais, Paris. Azerbaijani rug - "Muğan" (Karabakh school)[citation needed](Complete painting here).

Carpet detail, Flemish school, 16th century, Petit Palais, Paris. Azerbaijani rug - "Muğan" (Karabakh school)[citation needed](Complete painting here).

These are named after Hans Memling, who painted what may have been Armenian carpets in the last quarter of the fifteenth century, and are characterised by several lines coming off the motifs that end in "hooks", by coiling in on themselves through two or three 90° turns.[28][29]

-

Hans Memling's still life of a jug with flowers on a Memling carpet. The reverse has a portrait of a praying man. c. 1480-1485.

-

Flemish school, 16th century, Petit Palais, Paris.

Holbein carpets

Left image: Verrocchio's Madonna with Saint John the Baptist and Donatus 1475-1483.

Right image: Small-pattern Holbein carpet, Anatolia, 16th century.Main article: Holbein carpetThese in fact are seen in paintings from many decades earlier than Holbein, and are sub-divided into four types (of which Holbein actually only painted two); they are the commonest designs of Anatolian carpet seen in Western Renaissance paintings, and continued to be produced for a long period. All are purely geometric and use a variety of arrangements of lozenges, crosses and octagonal motifs within the main field. The sub-divisions are between:[30]

- Type I: Small-pattern Holbein. The motifs are small, and usually of several different types that recur regularly - see the Somerset House group portrait below.[31]

- Type II: now more often called Lotto carpets - see below.

- Type III: Large-pattern Holbein. The motifs in the field inside the border are large squares filled with decoration, placed regularly, with narrow strips between them containing no "gul" motifs. The carpet in Holbein's The Ambassadors is of this type.[32]

- Type IV: Large-pattern Holbein. The square compartments have octagons or other "gul" motifs from the small-pattern types between them.[33]

-

Master of Saint Giles, Mass of Saint Giles, c. 1500, with a Type III Holbein carpet.

-

French ambassador to England Jean de Dinteville in "The Ambassadors", by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1533. Holbein frequently used carpets in portraits, on tables for most sitters, but on the floor for Henry VIII. This is a "large-pattern Holbein", Type III.

-

Darmstadt Madonna by Hans Holbein the Younger, with donor portraits, on a Holbein Type III carpet. 1525–26 and 1528.

-

Portrait of Archbishop William Warham, with a large pattern Holbein Type IV carpet in the right corner, by Hans Holbein the Younger (1527).

Lotto carpets

Left image: The Alms of St. Anthony, by Lorenzo Lotto, 1542, with two magnificent Oriental carpets, the one in the foreground the type for the Lotto carpet, the other a "para-Mamluk".[34]

Right image: Western Anatolia knotted wool "Lotto carpet", 16th century, Saint Louis Art Museum.Main article: Lotto carpetPreviously known as Small-pattern Holbein Type II, but he never painted one, unlike Lorenzo Lotto, who did so several times, though he was not the first artist to show them. Lotto is also documented as owning a large carpet, though its pattern is unknown.

Though they look very different from Holbein Type I carpets, they are a development of the type, where the edges of the motifs, nearly always in yellow on a red ground, take off in rigid arabesques somewhat suggesting foliage, and terminating in branched palmettes. The type was common and long-lasting, and is also known as "Arabesque Ushak".[35]

Other examples

Italy

-

The Spanish painter Pedro Berruguete's Annunciation panel, late 15th century. The carpet may also be Spanish.

-

Oriental carpet in Piero della Francesca's The Brera Madonna 1460s.

-

Domenico Ghirlandaio's Madonna and Child enthroned with Saint, c. 1483, with a Holbein Type I.

-

Domenico Ghirlandaio's Madonna and Child enthroned between Angels and Saint c. 1486.

-

Oriental carpet in Tommaso di Piero's Sacra Conversazione, 1490-1500.

-

Carpets displayed over windows for a procession in Venice. Detail by Vittore Carpaccio, 1507

-

Giovanni Bellini's Naked Young Woman in Front of the Mirror, c. 1515.

-

Oriental carpet (a Star Ushak design) at the feet of the Doge in the 1534 Return of the Doge's Ring by Paris Bordone.

-

Federico Montefeltro with humanist writer Cristoforo Landino, Sandro Botticelli, circa 1460.

Early Netherlandish and Northern Renaissance

-

Jan Van Eyck's Madonna with Canon Van der Paele (1434). Origin of carpet unknown, as no comparable carpets survive.[36] Possibly Egyptian.

-

Small bedside rug in Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait (1434), which contains many elements that were extremely expensive at the time.

-

Hans Memling, but not a "Memling carpet".

-

Gerard David's Triptych of the Sedano family, 1523

-

Hans Holbein the Younger's Portrait of the merchant Georg Gisze, 1532.

England

-

Henry VIII standing on a star Ushak carpet, Hans Holbein the Younger c.1530.[37]

-

Edward VI standing on a Holbein carpet, c.1547.[38]

-

Elizabeth I of England c.1599, studio of Nicholas Hilliard

France

-

Portrait of Henry II standing on a Holbein carpet, by François Clouet.

17th century

Carpets remained an important way of enlivening the background of full-length portraits throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, for example in the English portraits of William Larkin.[39] The finely-knotted silk carpets woven in the time of Shah Abbas I at Kashan and Isfahan are rarely represented in paintings, as they were doubtless very unusual in European homes;[40] however, A Lady playing the Theorbo. by Gerard Terborch (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 14.40.617) shows such a carpet laid upon the table on which the lady's cavalier is sitting.[41] Floral "Isfahan" carpets of the Herat type, on the other hand, were exported in great numbers to Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands, and are often represented in interiors painted by Velásquez, Rubens, Van Dyck, Vermeer, Terborch, de Hooch, Bol and Metsu, where the dates established for the paintings provide a yardstick for establishing the chronology of the designs.[42] Anthony van Dyck's royal and aristocratic subjects had mostly progressed to Persian carpets, but less wealthy sitters are still shown with the Turkish types; in the American colonies Isaac Royall and his family were painted by Robert Feke in 1741, posed round a table spread with a Bergama rug.[43] From the mid-century European direct trade with India brought Mughal versions of Persian patterns to Europe. Painters of the Dutch Golden Age showed their skill by depiction of light effects on table-carpets, like Vermeer in his Music Lesson (Royal Collection). By this date they have become common in the homes of the reasonably well-to-do, as is shown by historical documentation of inventories, and even appear in brothel scenes from the prosperous Netherlands.[44]

By the end of the century Oriental carpets had lost much of their status as prestige objects, and the grandest sitters for portraits were more likely to be shown on the high-quality Western carpets, like Savonneries, now being produced, whose less intricate patterns were also easier to depict in a painterly manner. A number of Orientalist European painters continued to accurately depict Oriental carpets, now usually in Oriental settings.

-

Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset by William Larkin, 1613, standing on a Lotto carpet. Most of Larkin's full-length subjects stand on carpets.

-

Nicolas Regnier's Fortune-teller, 1626, Louvre.

-

Nicolas Tournier's Concert 1630-1635.

-

Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke, with his Family, by Anthony van Dyck, whose sitters had mostly moved on to Persian carpets.

-

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild, 1662, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

See also

- Pseudo-Kufic

- Renaissance painting

External links

- The Carpet Index: The Oriental Carpet in Early Renaissance Paintings

- Carpets in Western Europe During the Renaissance

Notes

- ^ a b Mack, p.75

- ^ a b Mack, p.74

- ^ King & Sylvester, 10-11

- ^ King & Sylvester, 17

- ^ Mack, p.74-75. Image

- ^ Mack, p.75. King & Sylvester, pp. 13, and 49-50.

- ^ First encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936 p.108

- ^ King & Sylvester, pp. 49-50. The Marby Rug, one of the finest examples, was preserved in Sweden. This is are shown about a third of the way down this page

- ^ King & Sylvester, p.15

- ^ Mack, p.76

- ^ King & Sylvester, p. 14

- ^ Carpaccio image

- ^ Mack, p.73-93

- ^ Mack, p.67

- ^ King & Sylvester, p. 20

- ^ King & Sylvester, 14

- ^ Mack, p.77

- ^ Mack, p.84. King & Sylvester, p. 58.

- ^ Mack, p.85.

- ^ Mack, p.90

- ^ Old Turkish carpets website

- ^ King & Sylvester

- ^ King and Sylvester, pp. 14-16, 56, 58.

- ^ King & Sylvester, 78

- ^ One shown here, about a third of the way down the page.

- ^ King & Sylvester, pp. 14, 26, 57-58. Campbell, p. 189.National Gallery zoomable image. There is a different type of carpet hung from the Virgin's house, at top center-right.

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 57

- ^ Todd Richardson, Plague, Weather, and Wool, AuthorHouse, 2009, p.182(344), ISBN 1438951876, 9781438951874

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 57.

- ^ King & Sylvester, pp. 26-27, 52-57. Campbell, p. 189.

- ^ Old Ottoman carpets, see also last note.

- ^ Old Ottoman carpets, Large-pattern Type III Holbein Carpets. See also note to the last paragraph.

- ^ Old Ottoman carpets, Large-pattern Type IV Holbein Carpets. See also note to the last paragraph.

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 17.

- ^ Cambell, p. 189. Old Ottoman carpets. Type II Holbein or "Lotto" Carpets. King and Sylvester, pp. 16, 67-70.

- ^ King and Sylvester, 20

- ^ Historic floors by Jane Fawcett p.156

- ^ Historic floors by Jane Fawcett p.157

- ^ King & Sylvester, 19

- ^ Examples in Polish collections led to their being miscalled "Polish carpets" in the 19th century, a misnomer that has stuck: "representations of 'Polish' silk rugs in paintings are rare" report Dimand and Mailey 1973, p.59.

- ^ Maurice Dimand and Jean Mailey, Oriental Rugs in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 60, fig.83.

- ^ Dimand and Mailey 1973, p 67, illustrating floral Herat rugs in A Visit to the Nursery by Gabriel Metsu (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.20), p. 67,fig. 94; Portrait of Omer Talon, by Philippe de Champaigne, 1649 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, p.70, fig. 98); Woman with a Water Jug, by Jan Vermeer (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 89.15.21, p.71, fig. 101

- ^ In the collection of Harvard University Law School; illustrated in Dimand and Mailey 1973, p.193, fig. 178. An earlier Bergama rug appears in the portrait of Abraham Grapheus by Cornelis de Vos, in Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp (noted by Dimand and Maily).

- ^ King & Sylvester, pp. 22-23

References

- Campbell, Gordon. The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Volume 1, "Carpet, S 2; History(pp. 187–193), Oxford University Press US, 2006, ISBN 0195189485, 9780195189483 Google books

- Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0520221311

- King, Donald and Sylvester, David eds. The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, From the 15th to the 17th century, Arts Council of Great Britain, London, 1983, ISBN 0728703629

Rugs and carpets Rugs Abadeh · Afghan · Ahar · Alcaraz · Arak · Ardabil · Azerbaijani · Bakshaish · Balouch · Bessarabian · Bidjar · Braided · Caucasian · Dhurrie · Eagle · Flokati · Heriz · Isfahan · Jozan · Kashan · Kashmar · Kashmir · Kilim · Kuba · Kurdish · Lilihan · Nain · Navajo · Oriental · Pakistani · Petate · Pirotan · Qom · Rya · Sarouk · Seraband · Seychour · Shiraz · Tabriz · Tibetan · Turkmen · Uzbek Julkhyr · Uzbek Napramach · War · YürükCarpets Ardabil · Armenian · Baharestan · Bakshaish · Bellini · Berber · Bergama · Bessarabian · Bradford · Caucasian · Coronation · Chiprovtsi · Crivelli · Fitted · Gabbeh · Hereke · Karabakh · Konya · Kuba · Holbein · Lilihan · Lotto · Memling · Milas · Persian · Red · Sarouk · Turkish · Ushak · Yomut · Tack strip · Underlay

Oriental carpets in Renaissance paintingPeople Places Cleaning Fabrics Manufacture A & M Karagheusian · Carpet One · Ghiordes knot · Knot density · Rubia · Rug hooking · Rug making · Savonnerie manufactoryCategories:- Renaissance art

- Iconography

- Rugs and carpets

- Orientalism

- Islamic art

-

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.