- Crystallographic defects in diamond

-

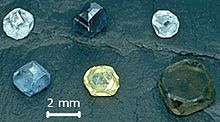

Imperfections in the crystal lattice of diamond are common. Such crystallographic defects in diamond may be the result of lattice irregularities or extrinsic substitutional or interstitial impurities, introduced during or after the diamond growth. They affect the material properties of diamond and determine to which type a diamond is assigned; the most dramatic effects are on the diamond color and electrical conductivity, as explained by the band theory.

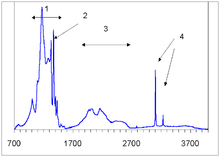

The defects can be detected by different types of spectroscopy, including electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), luminescence induced by light (photoluminescence, PL) or electron beam (cathodoluminescence, CL), and absorption of light in the infrared (IR), visible and UV parts of the spectrum. Absorption spectrum is used not only to identify the defects, but also to estimate their concentration; it can also distinguish natural from synthetic or enhanced diamonds.[1]

The number of defects in diamond whose microscopic structure has been reliably identified is rather large (many dozens), and only the major ones are briefly mentioned in this article.

Contents

Labeling of diamond centers

There is a tradition in diamond spectroscopy to label a defect-induced spectrum by a numbered acronym (e.g. GR1). This tradition has been followed in general with some notable deviations, such as A, B and C centers. Many acronyms are confusing though:[2]

- Some symbols are too similar (e.g., 3H and H3).

- Accidentally, same labels were given to different centers detected by EPR and optical techniques (e.g., N3 EPR center and N3 optical center have no relation).[3]

- Whereas some acronyms are logical, such as N3 (N for natural, i.e. observed in natural diamond) or H3 (H for heated, i.e. observed after irradiation and heating), many are not. In particular, there is no clear distinction between the meaning of labels GR (general radiation), R (radiation) and TR (type-II radiation).[2]

Defect symmetry

The symmetry of defects in crystals is described by the point groups. They differ from the space groups describing the symmetry of crystals by absence of translations, and thus are much fewer in number. In diamond, only defects of the following symmetries have been observed thus far: tetrahedral (Td), tetragonal (D2d), trigonal (D3d,C3v), rhombic (C2v), monoclinic (C2h, C1h, C2) and triclinic (C1 or CS).[2][4]

The defect symmetry allows predicting many optical properties. For example, one-phonon (infrared) absorption in pure diamond lattice is forbidden because the lattice has an inversion center. However, introducing any defect (even "very symmetrical", such as N-N substitutional pair) breaks the crystal symmetry resulting in defect-induced infrared absorption, which is the most common tool to measure the defect concentrations in diamond.[2]

An interesting symmetry related phenomenon has been observed[5] that when diamond is produced by the high-pressure high-temperature synthesis, non-tetrahedral defects align to the direction of the growth. Such alignment has been also been observed in gallium arsenide[6] and thus is not unique to diamond.

Extrinsic defects

Various elemental analyses of diamond reveal a wide range of impurities. They however mostly originate from inclusions of foreign materials in diamond, which could be nanometer-small and invisible in an optical microscope. Also, virtually any element can be hammered into diamond by ion implantation. More essential are elements which can be introduced into the diamond lattice as isolated atoms (or small atomic clusters) during the diamond growth. By 2008, those elements are nitrogen, boron, hydrogen, silicon, phosphorus, nickel, cobalt and perhaps sulfur. Manganese[7] and tungsten[8] have been unambiguously detected in diamond, but they might originate from foreign inclusions. Detection of isolated iron in diamond[9] has later been re-interpreted in terms of micro-particles of ruby produced during the diamond synthesis.[10] Oxygen is believed to be a major impurity in diamond,[11] but it has not been spectroscopically identified in diamond yet.[citation needed] Two electron paramagnetic resonance centers (OK1 and N3) have been assigned to nitrogen–oxygen complexes. However, the assignment is indirect and the corresponding concentrations are rather low (few parts per million).[12]

Nitrogen

The most common impurity in diamond is nitrogen, which can comprise up to 1% of a diamond by mass.[11] Previously, all lattice defects in diamond were thought to be the result of structural anomalies; later research revealed nitrogen to be present in most diamonds and in many different configurations. Most nitrogen enters the diamond lattice as a single atom (i.e. nitrogen-containing molecules dissociate before incorporation), however, molecular nitrogen incorporates into diamond as well.[13]

Absorption of light and other material properties of diamond are highly dependent upon nitrogen content and aggregation state. Although all aggregate configurations cause absorption in the infrared, diamonds containing aggregated nitrogen are usually colorless, i.e. have little absorption in the visible spectrum.[2] The four main nitrogen forms are as follows:

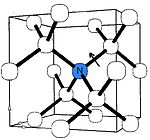

C-nitrogen center

The C center corresponds to electrically neutral single substitutional nitrogen atoms in the diamond lattice. These are easily seen in electron paramagnetic resonance spectra[14] (in which they are confusingly called P1 centers). C centers impart a deep yellow to brown color; these diamonds are classed as type Ib and are commonly known as "canary diamonds", which are rare in gem form. Most synthetic diamonds produced by high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) technique contain a high level of nitrogen in the C form; nitrogen impurity originates from the atmosphere or from the graphite source. One nitrogen atom per 100,000 carbon atoms will produce yellow color.[15] Because the nitrogen atoms have five available electrons (one more than the carbon atoms they replace), they act as "deep donors"; that is, each substituting nitrogen has an extra electron to donate and forms a donor energy level within the band gap. Light with energy above ~2.2 eV can excite the donor electrons into the conduction band, resulting in the yellow color.[16]

The C center produces a characteristic infrared absorption spectrum with a sharp peak at 1344 cm−1 and a broader feature at 1130 cm−1. Absorption at those peaks is routinely used to measure the concentration of single nitrogen.[17] Another proposed way, using the UV absorption at ~260 nm, has later been discarded as unreliable.[16]

Acceptor defects in diamond ionize the fifth nitrogen electron in the C center converting it into C+ center. The latter has a characteristic IR absorption spectrum with a sharp peak at 1332 cm−1 and broader and weaker peaks at 1115, 1046 and 950 cm−1.[18]

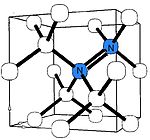

A-nitrogen center

The A center is probably the most common defect in natural diamonds. It consists of a neutral nearest-neighbor pair of nitrogen atoms substituting for the carbon atoms. The A center produces UV absorption threshold at ~4 eV (310 nm, i.e. invisible to eye) and thus causes no coloration. Diamond containing nitrogen predominantly in the A form as classed as type IaA.[19]

The A center is diamagnetic, but if ionized by UV light or deep acceptors, it produces an electron paramagnetic resonance spectrum W24, whose analysis unambiguously proves the N=N structure.[20]

The A center shows an IR absorption spectrum with no sharp features, which is distinctly different from that of the C or B centers. Its strongest peak at 1282 cm−1 is routinely used to estimate the nitrogen concentration in the A form.[21]

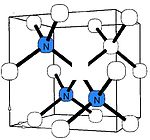

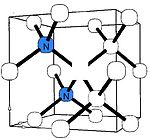

B-nitrogen center

There is a general consensus that B center (sometimes called B1) consists of a carbon vacancy surrounded by four nitrogen atoms substituting for carbon atoms.[1][2][22] This model is consistent with other experimental results, but there is no direct spectroscopic data corroborating it. Diamonds where most nitrogen forms B centers are rare and are classed as type IaB; most gem diamonds contain a mixture of A and B centers, together with N3 centers.

Similar to the A centers, B centers do not induce color, and no UV or visible absorption can be attributed to the B centers. Early assignment of the N9 absorption system to the B center have been disproven later.[23] The B center has a characteristic IR absorption spectrum (see the infrared absorption picture above) with a sharp peak at 1332 cm−1 and a broader feature at 1280 cm−1. The latter is routinely used to estimate the nitrogen concentration in the B form.[24]

Note that many optical peaks in diamond accidentally have similar spectral positions, which causes much confusion among gemologists. Spectroscopists use for defect identification the whole spectrum rather than one peak, and consider the history of the growth and processing of individual diamond.[1][2][22]

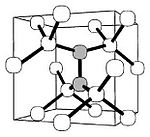

N3 nitrogen center

The N3 center consists of three nitrogen atoms surrounding a vacancy. Its concentration is always just a fraction of the A and B centers.[25] The N3 center is paramagnetic, so its structure is well justified from the analysis of the EPR spectrum P2.[3] This defect produces a characteristic absorption and luminescence line at 415 nm and thus does not induce color on its own. However, the N3 center is always accompanied by the N2 center, having an absorption line at 478 nm (and no luminescence).[26] As a result, diamonds rich in N3/N2 centers are yellow in color.

Boron

Diamonds containing boron as a substitutional impurity are termed type IIb. Only one percent of natural diamonds are of this type, and most are blue to grey.[27] Boron is acceptor in diamond: boron atoms have one less available electron than the carbon atoms; therefore, each boron atom substituting for a carbon atom creates an electron hole in the band gap that can accept an electron from the valence band. This allows red light absorption, and due to the small energy (0.37 eV)[28] needed for the electron to leave the valence band, holes can be thermally released from the boron atoms to the valence band even at room temperatures. These holes can move in an electric field and render the diamond electrically conductive (i.e., a p-type semiconductor). Few boron atoms are required for this to happen—a typical ratio is one boron atom per 1,000,000 carbon atoms.

Boron-doped diamonds transmit light down to ~250 nm and absorb some red and infrared light (hence the blue color); they may phosphoresce blue after exposure to shortwave ultraviolet light.[28] Apart from optical absorption, boron acceptors have been detected by electron paramagnetic resonance.[29]

Phosphorus

Phosphorus could be intentionally introduced into diamond grown by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) at concentrations up to ~0.01%.[30] Phosphorus substitutes carbon in the diamond lattice.[31] Similar to nitrogen, phosphorus has one more electron than carbon and thus acts as a donor; however, the ionization energy of phosphorus (0.6 eV)[32] is much smaller than that of nitrogen (1.7 eV)[33] and is small enough for room-temperature thermal ionization. This important property of phosphorus in diamond favors electronic applications, such as UV light emitting diodes (LEDs, at 235 nm).[34]

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is one of the most technological important impurities in semiconductors, including diamond. Hydrogen-related defects are very different in natural diamond and in synthetic diamond films. Those films are produced by various chemical vapor deposition (CVD) techniques in an atmosphere rich in hydrogen (typical hydrogen/carbon ratio >100), under strong bombardment of growing diamond by the plasma ions. As a result, CVD diamond is always rich in hydrogen and lattice vacancies. In polycrystalline films, much of the hydrogen may be located at the boundaries between diamond 'grains', or in non-diamond carbon inclusions. Within the diamond lattice itself, hydrogen-vacancy[35] and hydrogen-nitrogen-vacancy[36] complexes have been identified in negative charge states by electron paramagnetic resonance. In addition, numerous hydrogen-related IR absorption peaks are documented.[37]

It is experimentally demonstrated that hydrogen passivates electrically active boron[38] and phosphorus[39] impurities. As a result of such passivation, shallow donor centers are presumably produced.[40]

In natural diamonds, several hydrogen-related IR absorption peaks are commonly observed; the strongest ones are located at 1405, 3107 and 3237 cm−1 (see IR absorption figure above). The microscopic structure of the corresponding defects is yet unknown and it is not even certain whether or not those defects originate in diamond or in foreign inclusions. Gray color in some diamonds from the Argyle mine in Australia is often associated with those hydrogen defects, but again, this assignment is yet unproven.[41]

Nickel and cobalt

When diamonds are grown by the high-pressure high-temperature technique, nickel, cobalt or some other metals are usually added into the growth medium to facilitate catalytically the conversion of graphite into diamond. As a result, metallic inclusions are formed. Besides, isolated nickel and cobalt atoms incorporate into diamond lattice, as demonstrated through characteristic hyperfine structure in electron paramagnetic resonance, optical absorption and photoluminescence spectra,[42] and the concentration of isolated nickel can reach 0.01%.[43] This fact is by all means unusual considering the large difference in size between carbon and transition metal atoms and the superior rigidity of the diamond lattice.[2][43]

Numerous Ni-related defects have been detected by electron paramagnetic resonance,[5][44] optical absorption and photoluminescence,[5][44] both in synthetic and natural diamonds.[41] Three major structures can be distinguished: substitutional Ni,[45] nickel-vacancy[46] and nickel-vacancy complex decorated by one or more substitutional nitrogen atoms.[44] The "nickel-vacancy" structure, also called "semi-divacancy" is specific for most large impurities in diamond and silicon (e.g., tin in silicon[47]). Its production mechanism is generally accepted as follows: large nickel atom incorporates substitutionally, then expels a nearby carbon (creating a neighboring vacancy), and shifts in-between the two sites.

Although the physical and chemical properties of cobalt and nickel are rather similar, the concentrations of isolated cobalt in diamond are much smaller than those of nickel (parts per billion range). Several defects related to isolated cobalt have been detected by electron paramagnetic resonance[48] and photoluminescence,[5][49] but their structure is yet unknown.

Silicon

Silicon is a common impurity in diamond films grown by chemical vapor deposition and it originates either from silicon substrate or from silica windows or walls of the CVD reactor. It was also observed in natural diamonds in dispersed form.[50] Isolated silicon defects have been detected in diamond lattice through the sharp optical absorption peak at 738 nm[51] and electron paramagnetic resonance.[52] Similar to other large impurities, the major form of silicon in diamond has been identified with a Si-vacancy complex (semi-divacancy site).[52] This center is a deep donor having an ionization energy of 2 eV, and thus again is unsuitable for electronic applications.[53]

Si-vacancies constitute minor fraction of total silicon. It is believed (though no proof exists) that much silicon substitutes for carbon thus becoming invisible to most spectroscopic techniques because silicon and carbon atoms have the same configuration of the outer electronic shells.

Sulfur

Around the year 2000, there was a wave of attempts to dope synthetic CVD diamond films by sulfur aiming at n-type conductivity with low activation energy. Successful reports have been published,[54] but then dismissed[55] as the conductivity was rendered p-type instead of n-type and associated not with sulfur, but with residual boron, which is a highly efficient p-type dopant in diamond.

So far (2009), there is only one reliable evidence (through hyperfine interaction structure in electron paramagnetic resonance) for isolated sulfur defects in diamond. The corresponding center called W31 has been observed in natural type-Ib diamonds in small concentrations (parts per million). It was assigned to a sulfur-vacancy complex – again, as in case of nickel and silicon, a semi-divacancy site.[56]

Intrinsic defects

The easiest way to produce intrinsic defects in diamond is by displacing carbon atoms through irradiation with high-energy particles, such as alpha (helium), beta (electrons) or gamma particles, protons, neutrons, ions, etc. The irradiation can occur in the laboratory or in the nature (see Diamond enhancement – Irradiation); it produces primary defects named frenkel defects (carbon atoms knocked off their normal lattice sites to interstitial sites) and remaining lattice vacancies. An important difference between the vacancies and interstitials in diamond is that whereas interstitials are mobile during the irradiation, even at liquid nitrogen temperatures,[57] however vacancies start migrating only at temperatures ~700 0C.

Vacancies and interstitials can also be produced in diamond by plastic deformation, though in much smaller concentrations.

Isolated carbon interstitial

Isolated interstitial has never been observed in diamond and is considered unstable. Its interaction with a regular carbon lattice atom produces a "split-interstitial", a defect where two carbon atoms share a lattice site and are covalently bonded with the carbon neighbors. This defect has been thoroughly characterized by electron paramagnetic resonance (R2 center)[58] and optical absorption,[59] and unlike most other defects in diamond, it does not produce photoluminescence.

Interstitial complexes

The isolated split-interstitial moves through the diamond crystal during irradiation. When it meets other interstitials it aggregates into larger complexes of two and three split-interstitials, identified by electron paramagnetic resonance (R1 and O3 centers),[60][61] optical absorption and photoluminescence.[62]

Vacancy-Interstitial complexes

Most high-energy particles, beside displacing carbon atom from the lattice site, also pass it enough surplus energy for a rapid migration through the lattice. However, when relatively gentle gamma irradiation is used, this extra energy is minimal. Thus the interstitials remain near the original vacancies and form vacancy-interstitials pairs identified through optical absorption.[62][63][64]

Vacancy-di-interstitial pairs have been also produced, though by electron irradiation and through a different mechanism:[65] Individual interstitials migrate during the irradiation and aggregate to form di-interstitials; this process occurs preferentially near the lattice vacancies.

Isolated vacancy

Isolated vacancy is the most studied defect in diamond, both experimentally and theoretically. Its most important practical property is optical absorption, like in the color centers, which gives diamond green, or sometimes even green–blue color (in pure diamond). The characteristic feature of this absorption is a series of sharp lines called GR1-8, where GR1 line at 741 nm is the most prominent and important.[63]

The vacancy behaves as a deep electron donor/acceptor, whose electronic properties depend on the charge state. The energy level for the +/0 states is at 0.6 eV and for the 0/- states is at 2.5 eV above the valence band.[66]

Multivacancy complexes

Upon annealing of pure diamond at ~700 0C, vacancies migrate and form divacancies, characterized by optical absorption and electron paramagnetic resonance.[67] Similar to single interstitials, divacancies do not produce photoluminescence. Divacancies, in turn, anneal out at ~900 0C creating multivacancy chains detected by EPR[68] and presumably hexavacancy rings. The latter should be invisible to most spectroscopies, and indeed, they have not been detected thus far.[68] Annealing of vacancies changes diamond color from green to yellow-brown. Similar mechanism (vacancy aggregation) is also believed to cause brown color of plastically deformed natural diamonds.[69]

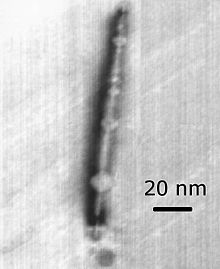

Dislocations

Dislocations are the most common structural defect in natural diamond. The two major types of dislocations are the glide set, in which bonds break between layers of atoms with different indices (those not lying directly above each other) and the shuffle set, in which the breaks occur between atoms of the same index. The dislocations produce dangling bonds which introduce energy levels into the band gap, enabling the absorption of light.[70] Broadband blue photoluminescence has been reliably identified with dislocations by direct observation in an electron microscope, however, it was noted that not all dislocations are luminescent, and there is no correlation between the dislocation type and the parameters of the emission.[71]

Platelets

Most natural diamonds contain extended planar defects in the <100> lattice planes, which are called platelets. Their size ranges from nanometers to many micrometres, and large ones are easily observed in an optical microscope.[72] For a long time, platelets were tentatively associated with large nitrogen complexes — nitrogen sinks produced as a result of nitrogen aggregation at high temperatures of the diamond synthesis. However, direct measurement of nitrogen in the platelets by EELS (an analytical technique of electron microscopy) revealed very little nitrogen.[72] The currently accepted model of platelets is a large regular array of carbon interstitials.[73]

Platelets produce sharp absorption peaks at 1359–1375 and 330 cm−1 in IR absorption spectra; remarkably, the position of the first peak depends on the platelet size.[72] As with dislocations, a broad photoluminescence centered at ~1000 nm was associated with platelets by direct observation in an electron microscope. By studying this luminescence, it was deduced that platelets have a "bandgap" of ~1.7 eV.[74]

Voidites

Voidites are octahedral nanometer-sized clusters present in many natural diamonds, as revealed by electron microscopy.[75] Laboratory experiments demonstrated that annealing of type-IaB diamond at high temperatures and pressures (>2600 0C) results in break-up of the platelets and formation of dislocation loops and voidites, i.e. that voidites are a result of thermal degradation of platelets. Contrary to platelets, voidites do contain much nitrogen, in the molecular form.[76]

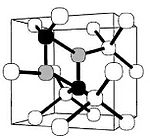

Interaction between intrinsic and extrinsic defects

Extrinsic and intrinsic defects can interact producing new defect complexes. Such interaction usually occurs if a diamond containing extrinsic defects (impurities) is either plastically deformed or is irradiated and annealed.

Most important is the interaction of vacancies and interstitials with nitrogen. Carbon interstitials react with substitutional nitrogen producing a bond-centered nitrogen interstitial showing strong IR absorption at 1450 cm−1.[77] Vacancies are efficiently trapped by the A, B and C nitrogen centers. The trapping rate is the highest for the C centers, 8 times lower for the A centers and 30 times lower for the B centers.[78] The C center (single nitrogen) by trapping a vacancy forms a famous nitrogen-vacancy center, which can be neutral or negatively charged;[79][80] the negatively charged state has potential applications in quantum computing. A and B centers upon trapping a vacancy create corresponding 2N-V (H3[81] and H2[82] centers, where H2 is simply a negatively charged H3 center[83]) and the neutral 4N-2V (H4 center[84]). The H2, H3 and H4 centers are important because they are present in many natural diamonds and their optical absorption can be strong enough to alter the diamond color (H3 or H4 – yellow, H2 – green).

Boron interacts with carbon interstitials forming a neutral boron–interstitial complex with a sharp optical absorption at 0.552 eV (2250 nm).[66] No evidence is known so far (2009) for complexes of boron and vacancy.[22]

In contrast, silicon does react with vacancies, creating the described above optical absorption at 738 nm.[85] The assumed mechanism is trapping of migrating vacancy by substitutional silicon resulting in the Si-V (semi-divacancy) configuration.[86]

A similar mechanism is expected for nickel, for which both substitutional and semi-divacancy configurations are reliably identified (see subsection "nickel and cobalt" above). In an unpublished study, diamonds rich in substitutional nickel were electron irradiated and annealed, with following careful optical measurements performed after each annealing step, but no evidence for creation or enhancement of Ni-vacancy centers was obtained.[46]

See also

References

- ^ a b c A.T. Collins "The detection of colour-enhanced and synthetic gem diamonds by optical spectroscopy" Diam. Rel. Mater. 12 (2003) 1976

- ^ a b c d e f g h J. Walker (1979). "Optical absorption and luminescence in diamond". Rep. Prog. Phys. 42 (10): 1605–1659. Bibcode 1979RPPh...42.1605W. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/42/10/001.

- ^ a b J. A. van Wyk "Carbon-13 hyperfine interaction of the unique carbon of the P2 (ESR) or N3 (optical) centre in diamond" J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 15 (1982) L981

- ^ A. M. Zaitsev (2001). Optical Properties of Diamond : A Data Handbook. Springer. ISBN 354066582X.

- ^ a b c d K. Iakoubovskii and A.T. Collins "Alignment of Ni- and Co-related centres during the growth of high-pressure–high-temperature diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16 (2004) 6897

- ^ R. A. Hogg et al. "Preferential alignment of Er–2O centers in GaAs: revealed by anisotropic host-excited photoluminescence" Appl. Phys. Lett. 68 (1996) 3317

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii and A. Stesmans "Characterization of Defects in as-Grown CVD Diamond Films and HPHT Diamond Powders by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance" phys. stat. sol. (a) 186 (2001) 199

- ^ S. Lal et al. "Defect photoluminescence in polycrystalline diamond films grown by arc-jet chemical-vapor deposition" Phys. Rev. B 54 (1996) 13428

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii and G. J. Adriaenssens "Evidence for a Fe-related defect centre in diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14 (2002) L95

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii and G. J. Adriaenssens "Comment on Evidence for a Fe-related defect centre in diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14 (2002) 5459

- ^ a b W. Kaiser and W. L. Bond "Nitrogen, A Major Impurity in Common Type I Diamond" Phys. Rev. 115 (1959) 857.

- ^ M.E. Newton and J.M. Baker "14N ENDOR of the OK1 centre in natural type Ib diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1 (1989) 10549

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii et al. "Nitrogen incorporation in diamond films homoepitaxially grown by chemical vapour deposition" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 12 (2000) L519

- ^ W. V. Smith et al. "Electron-Spin Resonance of Nitrogen Donors in Diamond" Phys. Rev. 115 (1959) 1546

- ^ Nassau and Kurt (1980) "Gems made by man" Gemological Institute of America, Santa Monica, California, ISBN 0-87311-016-1, p. 191

- ^ a b K Iakoubovskii and G J Adriaenssens "Optical transitions at the substitutional nitrogen centre in diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 12 (2000) L77

- ^ I. Kiflawi et al. "Infrared-absorption by the single nitrogen and a defect centers in diamond" Phil. Mag. B 69 (1994) 1141

- ^ S. C. Lawson et al. "On the existence of positively charged single-substitutional nitrogen in diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 10 (1998) 6171

- ^ G. Davies "The A nitrogen aggregate in diamond-its symmetry and possible structure" J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 9 (1976) L537

- ^ O. D. Tucker et al. "EPR and 14N electron-nuclear double-resonance measurements on the ionized nearest-neighbor dinitrogen center in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 50 (1994) 15586

- ^ S. R. Boyd et al. "The relationship between infrared absorption and the A defect concentration in diamond" Phil. Mag. B 69 (1994) 1149

- ^ a b c A. T. Collins "Things we still don’t know about optical centres in diamond" Diam. Relat. Mater. 8 (1999) 1455

- ^ A.A. Shiryaev et al. "High-temperature high-pressure annealing of diamond: Small-angle X-ray scattering and optical study" Physica B 308–310 (2001) 598

- ^ S. R. Boyd et al. "Infrared absorption by the B nitrogen aggregate in diamond" Phil. Mag. B, 72 (1995) 351

- ^ B. Anderson, J. Payne, R.K. Mitchell (ed.) (1998) "The spectroscope and gemology", p. 215, Robert Hale Limited, Clerkwood House, London. ISBN 0-7198-0261-X

- ^ M. F. Thomaz and G. Davies "The Decay Time of N3 Luminescence in Natural Diamond" Proc. Roy. Soc. A 362 (1978) 405

- ^ M. O'Donoghue (2002) "Synthetic, imitation & treated gemstones", Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Great Britain. ISBN 0750631732, p.52

- ^ a b A.T. Collins (1993). "The Optical and Electronic Properties of Semiconducting Diamond". Philosophical Transactions: Physical Sciences and Engineering 342 (1664): 233. Bibcode 1993RSPTA.342..233C. doi:10.1098/rsta.1993.0017.

- ^ C.A.J. Ammerlaan and R. van Kemp "Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in semiconducting diamond" J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 18 (1985) 2623

- ^ T. Kociniewski et al. "n-type CVD diamond doped with phosphorus using the MOCVD technology for dopant incorporation" Phys. Stat. Solidi (a) 203 (2006) 3136

- ^ M. Hasegawa et al. "Lattice location of phosphorus in n-type homoepitaxial diamond films grown by chemical-vapor deposition" Appl. Phys. Lett. 79 (2001) 3068

- ^ K. Haenen et al. "n-type CVD diamond doped with phosphorus using the MOCVD technology for dopant incorporation" Phys. Stat. Solidi (a) 181 (2000) 11

- ^ R.G. Farrer "On the substitutional nitrogen donor in diamond" Sol. St. Commun. 7 (1969) 685

- ^ S. Koizumi et al. "Ultraviolet Emission from a Diamond pn Junction" Science 292 (2001) 1899

- ^ C. Glover et al. "Hydrogen Incorporation in Diamond: The Vacancy-Hydrogen Complex" Phys. Rev. Lett. 92 (2004) 135502

- ^ C. Glover et al. "Hydrogen Incorporation in Diamond: The Nitrogen-Vacancy-Hydrogen Complex" Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 (2003) 185507

- ^ F. Fuchs et al. "Hydrogen induced vibrational and electronic transitions in chemical vapor deposited diamond, identified by isotopic substitution" Appl. Phys. Lett. 66 (1995) 177

- ^ J. Chevallier et al. "Hydrogen–boron interactions in p-type diamond" Phys. Rev. B 58 (1998) 7966

- ^ J. Chevallier et al. "Hydrogen in n-type diamond" Diam. Rel. Mater. 11 (2002) 1566

- ^ Z. Teukam et al. "Shallow donors with high n-type electrical conductivity in homoepitaxial deuterated boron-doped diamond layers" Nature Materials 2 (2003) 482

- ^ a b "Optical characterization of natural Argyle diamonds" Diam. Relat. Mater. 11 (2002) 125

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii and G. Davies "Vibronic effects in the 1.4-eV optical center in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 70 (2004) 245206

- ^ a b A.T. Collins et al. "Correlation between optical absorption and EPR in high-pressure diamond grown from a nickel solvent catalyst" Diam. Rel. Mater. 7(1998) 333

- ^ a b c V. A. Nadolinny et al. "A study of 13C hyperfine structure in the EPR of nickel-nitrogen-containing centres in diamond and correlation with their optical properties" 1999 J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 11 7357

- ^ J. Isoya et al. "Fourier-transform and continuous-wave EPR studies of nickel in synthetic diamond: Site and spin multiplicity" Phys. Rev. B 41 (1990) 3905

- ^ a b K. Iakoubovskii "Ni-vacancy defect in diamond detected by electron spin resonance" Phys. Rev. B 70 (2004) 205211

- ^ G.D. Watkins "Defects in irradiated silicon: EPR of the tin-vacancy pair" Phys. Rev. B 12 (1975) 4383

- ^ D.J. Twitchen et al. "Identification of cobalt on a lattice site in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 61 (2000) 9

- ^ S.C. Lawson et al. "Spectroscopic study of cobalt-related optical centers in synthetic diamond" J. Appl. Phys. 79 (1996) 4348

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii et al. "Optical characterization of some irradiation-induced centers in diamond" Diam. Rel. Mater. 10 (2001) 18

- ^ C. D. Clark et al. "Silicon defects in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 51 (1995) 16681

- ^ a b A. M. Edmonds et al. "Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of silicon-related defects in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 77 (2008) 245205

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii and G.J. Adriaenssens "Luminescence excitation spectra in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 61 (2000) 10174

- ^ I. Sakaguchi et al. "Sulfur: A donor dopant for n-type diamond semiconductors" Phys. Rev. B 60 (1999) R2139

- ^ R. Kalish et al. "Is sulfur a donor in diamond?" Appl. Phys. Lett. 76 (2000) 757

- ^ J. M. Baker et al. "Electron paramagnetic resonance of sulfur at a split-vacancy site in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 78 (2008) 235203

- ^ M.E. Newton et al. "Recombination-enhanced diffusion of self-interstitial atoms and vacancy–interstitial recombination in diamond" Diam. Rel. Mater. 11 (2002) 618

- ^ D. C. Hunt et al. "Identification of the neutral carbon <100>-split interstitial in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 61 (2000) 3863

- ^ H. E. Smith et al. "Structure of the self-interstitial in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 69 (2004) 045203

- ^ D. J. Twitchen et al. "Electron-paramagnetic-resonance measurements on the di-<001>-split interstitial center (R1) in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 54 (1996) 6988

- ^ D. C. Hunt et al. "EPR data on the self-interstitial complex O3 in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 62 (2000) 6587

- ^ a b K. Iakoubovskii et al. "Evidence for vacancy-interstitial pairs in Ib-type diamond" Phys. Rev. B 71 (2005) 233201

- ^ a b I. Kiflawi et al. "Electron irradiation and the formation of vacancy–interstitial pairs in diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 19 (2007) 046216

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii et al. "Annealing of vacancies and interstitials in diamond" Physica B 340–342 (2003) 67

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii et al. "Electron spin resonance study of perturbed di-interstitials in diamond" Phys. Stat. Solidi (a) 201 (2004) 2516

- ^ a b S. Dannefaer and K. Iakoubovskii "Defects in electron irradiated boron-doped diamonds investigated by positron annihilation and optical absorption" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 20 (2008) 235225

- ^ D. J. Twitchen et al. "Electron-paramagnetic-resonance measurements on the divacancy defect center R4/W6 in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 59 (1999) 12900

- ^ a b K. Iakoubovskii and A. Stesmans "Dominant paramagnetic centers in 17O-implanted diamond" Phys. Rev. B 66 (2002) 045406

- ^ L. S. Hounsome et al. "Origin of brown coloration in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 73 (2006) 125203

- ^ A.T. Kolodzie and A.L. Bleloch Investigation of band gap energy states at dislocations in natural diamond. Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge; Cambridge, England.

- ^ P. L. Hanley, I. Kiflawi, A. R. Lang "On Topographically Identifiable Sources of Cathodoluminescence in Natural Diamonds" Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. A 284 (1977) 329

- ^ a b c I. Kiflawi et al. "'Natural' and 'man-made' platelets in type-Ia diamonds" Phil. Mag. B 78 (1998) 299

- ^ J. P. Goss et al. "Extended defects in diamond:?The interstitial platelet" Phys. Rev. B 67 (2003) 165208

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii and G. J. Adriaenssens "Characterization of platelet-related infrared luminescence in diamond" Phil. Mag. Lett. 80 (2000) 441

- ^ J.H. Chen et al. "Voidites in polycrystalline natural diamond" Phil. Mag. Lett. 77 (1988) 135

- ^ I. Kiflawi and J. Bruley "The nitrogen aggregation sequence and the formation of voidites in diamond" Diam. Rel. Mater. 9 (2000) 87

- ^ I. Kiflawi et al. "Nitrogen interstitials in diamond" Phys. Rev. B 54 (1996) 16719

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii and G.J. Adriaenssens "Trapping of vacancies by defects in diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 13 (2001) 6015

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii et al. "Photochromism of vacancy-related centres in diamond" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 12 (2000) 189

- ^ Y. Mita "Change of absorption spectra in type-Ib diamond with heavy neutron irradiation" Phys. Rev. B 53 (1996) 11360

- ^ G. Davies et al. "The H3 (2.463 eV) Vibronic Band in Diamond: Uniaxial Stress Effects and the Breakdown of Mirror Symmetry" Proc. Roy. Soc. A 351 (1976) 245

- ^ S.C. Lawson et al. "The 'H2' optical transition in diamond: the effects of uniaxial stress perturbations, temperature and isotopic substitution" J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 4 (1992) 3439

- ^ Y. Mita, Y. Nisada, K. Suito, A. Onodera and S. Yazu "Photochromism of H2 and H3 centres in synthetic type Ib diamonds" J. Phys: Condens. Matter 2 (1990) 8567

- ^ E. S. De Sa and G. Davies "Uniaxial Stress Studies of the 2.498 eV (H4), 2.417 eV and 2.536 eV Vibronic Bands in Diamond" Proc. Roy. Soc. A 357 (1977) 231

- ^ A.T. Collins et al. "The annealing of radiation damage in De Beers colourless CVD diamond" Diam. Rel. Mater. 3 (1994) 932

- ^ J.P. Goss, R. Jones, S.J. Breuer, P.R. Briddon, S. Oberg, "The Twelve-Line 1.682 eV Luminescence Center in Diamond and the Vacancy-Silicon Complex" Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 (1996) 3041

Categories:- Diamond

- Crystallographic defects

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.