- Kunbi

-

This article is about the Kunbi community in Maharashtra. For other uses, see Kunbi (disambiguation).

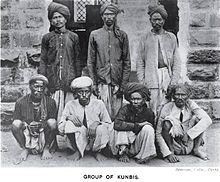

Kunbi (Marathi: कुणबी, Gujarati: કુનબી, alternatively Kanbi) is a generic term applied to castes of traditionally non-elite tillers in Western India.[1][2][3][4] These include the Dhonoje, Ghatole, Hindre, Jadav, Jhare, Khaire, Lewa (Leva Patil), Lonari and Tirole communities of Vidharbha. [5] The communities are largely found in the state of Maharashtra but also exist in the states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala and Goa. Kunbis are included in the Other Backward Classes (OBC) in Maharashtra.[5][a][b]

Sant Tukaram, one of the most revered Varkari saints of the Bhakti tradition of Maharashtra belonged to this community.[c] Most of the Mawalas serving in the armies of the Maratha Empire under Shivaji came from the community. The Shinde and Gaekwad dynasties of the Maratha Empire are originally of Kunbi origin. In the fourteenth century and later, several Kunbis who had taken up employment as military men in the armies of various rulers underwent a process of Sanskritization and hence started identifying themselves as Marathas. The boundary between the Marathas and the Kunbi however became obscure in the early 20th century due to the effects of colonization, and the two groups came to form one block, the Maratha-Kunbi.

Tensions along caste lines between the Kunbi and the Dalit communities were seen in the Khairlanji killings, and the media have also reported sporadic instances of violence against Dalits. Other inter-caste issues include the forgery of caste certificates by politicians, mostly in the grey Kunbi-Maratha caste area, to allow them to run for elections from wards reserved for OBC candidates. In April 2005 the Supreme Court of India ruled that the Marathas are not a sub-caste of Kunbis.

Contents

Etymology

According to the Anthropological Survey of India, the term Kunbi is derived from kun and bi meaning people and seeds respectively.[12] Fused together, the two terms mean "those who germinate more seeds from one seed".[12] Another etymology states that Kunbi is believed to have come from the Marathi word kunbawa, or Sanskrit kur, "agricultural tillage".[13] Yet another etymology states that Kunbi derives from kutumba (family), or from the Dravidian kul, "husbandman" or "labourer".[14] Thus anyone who took up the occupation of a cultivator could be brought under the generic term Kunbi.[15] Russel and Lal imply that the derivation from kun (root) or kan (grain) combined with bi (seed) is not probable.[16] G. S. Ghurye has posited that while the term may "signify the occupation of the group, viz., that of cultivation ... it is not improbable that the name may be of tribal origin."[17]

Other spellings and variants include: Kulambi (Deccan), Kulwadi (South Konkan), Kanbi (Gujarat), Kulbi (Belgaum), Reddies (Andhra Pradesh), Kurmi (Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand).[16] Singh and Lal also report that Cocoona is synonymous with Kunbi in Gujarat.[12]

Demographics

Caste population in Maharashtra in 1931[18] Community Population Maratha 52,45,040 Kunbi 21,16,500 Brahmin 9,14,757 Mali caste 7,05,799 Bharwad 4,09,935 Veershaiva Lingayat 3,16,225 There are a total of 305 communities in Maharashtra of which 161 (52.8%) are rural, 37 (12.1%) are urban, 97 (31.8%) are suburban and 97 (31.8%) are rural-urban.[19] The Kunbi, along with the Marathas and Mali, make the main peasant communities in the state.[20]

Russell and Lal report that the population of the Kunbis in the British Indian Central Provinces in 1911 was 1,400,000 and that Kunbis were present in the Nagpur, Chanda, Bhandara, Wardha, Nimar and Betul districts of the province.[21] They report that the population was 800,000 in Berar in the same year.[21] In 1981 the population of Kunbis in the Dangs district was recorded at 35,214.[12] Older gazetteers of various relevant districts record two-three other agricultural castes in addition to the Kunbis.[22] These additional castes include the Mali at 53,000 and Kunbi are put at 397,000 in the Pune district.[22] The Sholapur gazetteer clubs the Kunbi and the Marathas together to a total of 180,000 in 1881.[22] Marathas and Kunbis are recorded under the common heading of Kunbi in the census of 1881.[22][d] The group is often associated with the Kurmi caste, though scholars differ as to whether the terms are synonymous.[23][24] In 2006, the Indian government announced that Kurmi was considered synonymous with the Kunbi and Yellam castes in Maharashtra.[25]

Maratha-Kunbi

There appears to have been very little information on the significantly large group of the Maharashtrian agricultural castes, known as Maratha-Kunbis, as late as the nineteenth century.[27] Both individual terms, Kunbi and Maratha are equally complex.[27] The term Maratha, amongst other meanings, referred to all speakers of the Marathi language in the fourteenth century.[27] An example of this is the record of the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta whose use of the term included multiple castes who spoke Marathi.[28] Several years later, as the Bahamani kings and other rulers started employing the local population in their military, the term Maratha evolved to have a martial connotation. Those who were not associated with the term Maratha and were not untouchables at the same time started identifying themselves as Kunbi.[28] According to the Stewart Gordon, the so-called Marathas now differentiated themselves from the others such as the cultivators (Kunbi), iron-workers and tailors.[29] Thus at lower status levels of the members of the group, the term Kunbi was applied to those who tilled the land and it was possible for outsiders to become Kunbi, an example of which is recorded by Enthoven.[27] Enthoven observed that it was very common for Kolis or fishermen to take up agriculture and become Kunbis.[27] In the eighteenth century, under the Peshwas, newer waves of villagers joined the armies of the Maratha Empire.[30] These newer military men started seeing themselves as Marathas too, thus obscuring boundary between the Marathas and Kunbi. This differentiating boundary between the Marathas and Kunbis thus became unclear giving rise to a new category, the "Maratha-Kunbi".[30] While this view of the term was common amongst colonial European observers of the eighteenth century,[31] the European observers were ignorant about the evidence of caste connotations of the term.[32] It was true that the dividing line between the Maratha and Kunbi was obscure but there was evidence of certain families calling themselves Assall Marathas or true Marathas.[32][f] The Assal Marathas claimed to be Kshatriyas in the Varna hierarchy and claimed lineage from the Rajput clans of north India.[32] The rest, the Kunbi, accepted that they came lower in the Varna hierarchy.[32] Thus while the Maratha caste emerged from the Kunbi through the Sanskritisation process, the two consolidated in to a single block due to the social reforms as well as political and economic development that took place during British rule in early 20th century .[33]

The British installed Chatrapati Pratapsinh Bhonsle, a descendant of Shivaji, noted in his diary in the 1820s – 1830s period that the Gaekwads, another powerful Maratha dynasty had Kunbi origins.[34] He notes further "These days, when the Kunbis and others grow wealthy, they try to pollute our caste. If this goes on, dharma itself will not remain. Each man should stick to his own caste, but in spite of this these men are trying to spread money around in our caste. But make no mistake, all Kshatriyas will look to protect their caste in this matter.[34] Later, in September 1965, writing in the in the Marathi Dnyan Prasarak newspaper and addressing the changing meaning of the term Maratha and the social mobility of the day, an author first notes the origins of the Maratha-Kunbi cluster of castes, the eating habits and living conditions of the people of Maharashta.[35] The author then states how only a very small circle of families, like those of Shivaji Bhonsale, can claim the Kshatriya status.[35] The author states further that these Kshatriya families have not been able to stop the inroads made by the wealthy and powerful Kunbis who had bought their way into Kshatriya status through wealth and inter-marriages.[35] Of the most powerful Maratha dynasties, the Shindes (later anglicized to Scindia) were of Kunbi origin.[26][g] A "Marathaisation" of the Kunbis has been seen between the censuses of 1901 and 1931 which shows a gradually declining number of Kunbis resulting from more and more Kunbis identifying themselves as Marathas.[36] Lele records in 1990 that a subset of the Maratha-Kunbi group of castes became the political elite in the state of Maharashtra starting in sixties and seventies and have continued to be the elites till today.[37] The elite Maratha-Kunbis have institutionalised their ideology of agrarian development through their control of the Congress party.[37] The state Government of Maharashtra does not recognize a group called Maratha-Kunbi.[38]

According to Irawati Karve, the Marata-Kunbi form over 40 percent of the population of Western Maharashtra.[39] Later in 1990, Lele records that the Maratha-Kunbi group of castes account for 31% of the population and is found all over Maharashtra.[33]

Kunbi communities from Vidarbha region of Maharashtra

In Maharashtra, the Kunbi communities include the Dhonoje, Ghatole, Hindre, Jadav, Jhare, Khaire, Lewa (Leva Patil), Lonari and the Tirole communities.[5] According to the Anthropological Survey of India, of these nine castes, the Jadav and Tirole self-identify as Kshatriya, the Leva as Vaishya and the rest as Shudra.[40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47] The Lonari used to refer to themselves as Chhatriya Lonari Kunbi, but since their inclusion in the classification "Other Backward Classes," they have dropped the "Chhatriya".[48] The names of subsets of the Kunbi in Berar, according to Edward Balfour, were Tirale, Maratha, Bawane, Khaire, Khedule, and Dhanoje.[13] In a strict interpretation of the caste system, the word Kunbi does not identify a caste but rather a status, just as the word Rajput.[49] All Kunbi communities of Maharashtra speak Marathi and use the Devanagri script for written communication.[5] In Gujarat, the Anthropological Survey of India records that Kunbis have benefited economically from the government development programmes.[4] While both, boys and girls receive formal education, the drop-out rate of girls is higher due to economic reasons.[50] While diet of the Kunbi communities vary between vegetarianism and non-vegetarianism, most and perhaps all of the communities abstain from consumption of pork and beef.[5] Based on an analysis of family names of Kunbi castes like the Tirale and Bowne, Russell and Lal conclude that the Kunbi are largely made up of aboriginal tribes.[51]

Over the centuries the community has produced the prominent Varkari saint of the Bhakti tradition, Sant Tukaram and the Mawalas.[52][53][h] Like numerous other communities such as the Mahar, Mehra, Bhil, Koli, etc. and the Brahmin groups, the Kunbi perceive themselves as an indigenous community.[19][i]

Dhonoje

The Kunbi Dhonoje are primarily a community of land-owning agriculturists with deep roots in Maharashtra,[55] however, their origin and historical background are unknown.[56] The Dhanoje get their name from raising small stock or dhan,[57] which comes from Dhangar, another caste in Maharashtra. [58] Their home districts are primarily the Chandrapur, Gadchiroli, Bhandara and Nagpur districts of the Vidharbha region in Maharashtra.[56] The Anthropological Survey of India records in 2003 that while Hindi is spoken by the community while communicating with outsiders, the women of the community can only understand and not speak Hindi.[56] The Dhonoje observe strict endogamy with marriages being mostly arranged by family elders.[40] Kunbi Dhonoje males marry between 20 and 25 whereas the females marry earlier between 18 and 22.[40]

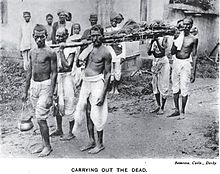

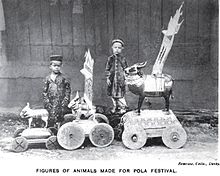

Dhonojes engage a Brahmin priest for conducting their marriage, birth and death rituals.[59] Cremation of the dead is the norm, burial the exception for those less than 11 years of age.[60] Common places of pilgrimage include Nashik, Pandharpur, Ramtek and Tuljapur.[55] Important Hindu festivals observed include Vaisakhi, Akadi, Yatra, Rakshabandhan, Dussera, Diwali and Holi.[55] All women and most men are vegetarian though some are occasional non-vegetarians.[56]

Most Dhonojes live in extended families but there are an increasing number of nuclear families in proportion with breaking away from the traditional occupation and urban migration.[61] In a multiethnic village, it is not possible to tell Kunbi Dhonoje by their surname alone.[40] Formal education has had a positive impact on the younger generation of the Dhonoje women.[60]

Although Hindus, they are known to conduct a fair or urus in reverence of the Muslim saint, Dawal Malik.[62]

Ghatole

The community name Ghatole is derived from Ghat meaning a hilly range.[63] The community is known to have originally dwelt in the ghats of the Sahyadri ranges.[64] The community belongs mainly to the western part of the Vidhabha region of Maharashtra. Oral tradition speaks of their arrival from the Sahyadris in Panchimhat.[63] In Vidharbha, they live mostly in the Aurangabad, Nashik, Buldhana, Amravati, Yavatmal, Parbhani and Akola districts.[63] The Ghatole claim to be the same as the economically and numerically superior Tirole or Tilole.[63] Per their oral tradition, those families which interrupted their migration march from the Ghats became the Ghatole whereas those who continued their journey eastwards became the Tirole Kunbi.[63] Despite the oral tradition, the two communities are now two distinct communities due to the strict endogamy for several generations and due to the geographical barriers.[65] All women and most men are vegetarian though some are occasionally non-vegetarians who keep their utensils separate and usually cook outside of the family kitchen.[41] Marriages are generally arranged and families are extended rather than nuclear.[41] Locations of pilgrimage are Nasik, Shirdi, Tuljapur and Pandharpur.[66] According to a report in 2009, the Ghatole Kunbi community in Akola and Washim areas of Vidharbha had preference for the Shivsena party than its political rivals.[67]

Hindre or Hendre

The Kunbi Hindre are synonymous with the Hindre Patils as far as their perceived distribution in the Vidharbha region of Maharashtra in the districts of Nanded, Parbhani, Yeotmal and Akola is concerned.[68] There are no further subdivisions of the community.[42] The community is said to have migrated from the Sahyadri ranges to the central Vidharbha region.[68] The community does not have an oral tradition of the etymology of the word Hindre or the history of their migration, hence their own origin is unknown to the Hindre themselve; while the Hindre were grouped with the Kunbis of the Khandesh region in early ethnographical studies, the origin of the community is not known.[68] Their numerical numbers have not been properly recorded in any official records and since the community is only found in certain rural districts, the Anthropological Survey of India estimates their population to be in thousands or in lakhs.[68] While the traditional occupation of the Hindre Kunbis is agriculture, better educational opportunities and urbanization has resulted in a disruption of their traditional economy which has caused many of the contemporary Hindre to pursue diversified occupations.[69]

The main language of the community is Marathi with Devanagri script for written communication and community members who visit urban areas for business reasons are able to communicate in broken Hindi.[68] The communities' traditional dress is similar to other peer communities.[68] All women and the majority of the men are vegetarians, some are occasional non-vegetarians.[68] Consumption of tea is common, mainly to overcome fatigue.[42]

Hindre are strictly endogamous[42] and their marriages are arranged.[70] Child marriages were practiced in the past but the age of marriage in 2003 has been recorded as being between 20–25 for males and 17 to 22 for females.[42] Cremation of the dead is the norm, exceptions being burial of the stillborn and babies who are a few months old.[71] Brahmin priests are employed for the Hindu rituals.[72] Main festivals of the Hindre include Vaishakhi, Akhadi, Yatra, Rakshabandhan, Dussera and Holi.[72] Places of pilgrimage include Pandharpur, Tuljapur, Ramtek, Nashik and Saptashringi.[68] The traditional caste council which existed in the 20th century for solving issues like divorces and social issues has been supplanted by the statutory gram panchayat of the state government.[72] Common surnames are Jaitale, Wankhed, Chouhan, Gawande, Mahale, Bhoir, Choudhary, Jadhav, etc. and it is not possible to identify a Hindre Kunbi on the basis of surname alone in a multi-ethnic village.[42] Changes in surnames have been recorded, an example of which is the changing of Chouhan to Jaitale.[42]

Jadhav

It is not known how the Jadhav came to be known by that name or when and how they were brought under the generic term Kunbi.[14] The home districts of the Jadhav Kunbi are Amaravati, Yavatmal, and Nagpur.[14] The community is strictly endogamous and consanguinal marriages with the maternal cousin are preferred over the paternal cousin[73] However the number of marriages of such nature are low.[43] Marriages are arranged and the preferred age for males is 22 or more and that for the women being 18 or more but these ages are now increasing as of 2003.[74] Cremation of the dead is the norm, burial being the exception for children and for those who have died of snake bites.[75] Brahmins are employed for naming and marriage ceremonies.[76] Surnames are varied and their origins are unknown but they are generally formed from the place of their dwelling, key events in the family from past generations or the names may simply bear a reference to an animate or inanimate object.[43] Amongst the rural Jadhavs, the traditional caste council has been replaced by the Akhil Bharatiya Jadhav Kunbi Samaj, a registered regional council located in Nagpur which also engages in social work.[75] The rulings of the statutory gram panchayat are also abided by at the village level.[75] Jadhav males are non-vegetarian but the women generally do not eat meat.[14] There are no further subdivisions amongst the Jadhavs.[14]

Jhare or Jhade

The name of the Jhade or Jhare Kunbi community, also known as the Jhadpi, comes from Jhadi meaning forest.[77] The home districts of the Jhade are Nagpur, Bhandara, Akola and Amravati.[77] The Jhade of the Bhadara district are also known as the Bowne, meaning 52 in Marathi, due to the high revenue of

52 lakh generated by them for the Mughal administration.[78] In 1916, the Jhade are recorded by Russsell and Hiralal as belonging to the Gond stock[77] The same ethnographic records state that the Jhade are the earliest immigrants to the Nagpur area.[77] Contemporary Jhade and Bowne contest this claim since they do not have any oral tradition of this nature.[77] Marriages are arranged and typical age of marriage is between 22 to 25 and between 16 to 20 for men and women respectively.[77] Marriages with maternal cousins are preferred.[77] Cremation of the dead is the norm, the exceptions being those who die before five years of age.[79] The Jhade do not employ the services of a Brahmin priest to carry out the death rites.[79] Common Jhade surnames are Katode, Jhanjad, Toukar, Baraskar, Khokle, Shende, Bhoie, Dhenge, Tejare, Bandobhnje, Waghaye, Trichkule, Baraskar, Khawas, Bhuse, etc.[78] The Anthropological Survey of India states in 2003 that the Jhade boys and girls have access to formal education who mostly go on to attain high school education.[80] The Survey also states that the community also has access to modern day amenities like electricity, health centres, motorable roads, public transport, post offices, drinking water and fair price shops of the Indian Public Distribution System.[80] Some family names of the Bowne recorded in Russel and Lal in 1916 with their English meanings are: Kantode (broken ear), Nagtode (broken nose), Dukkarmare (a pig killer), Titarmare (pigeon killer), Ghodmare (horse killer), Waghmare (tiger killer), Gadhe (a donkey), and Lute (a plunderer).[51][j]

52 lakh generated by them for the Mughal administration.[78] In 1916, the Jhade are recorded by Russsell and Hiralal as belonging to the Gond stock[77] The same ethnographic records state that the Jhade are the earliest immigrants to the Nagpur area.[77] Contemporary Jhade and Bowne contest this claim since they do not have any oral tradition of this nature.[77] Marriages are arranged and typical age of marriage is between 22 to 25 and between 16 to 20 for men and women respectively.[77] Marriages with maternal cousins are preferred.[77] Cremation of the dead is the norm, the exceptions being those who die before five years of age.[79] The Jhade do not employ the services of a Brahmin priest to carry out the death rites.[79] Common Jhade surnames are Katode, Jhanjad, Toukar, Baraskar, Khokle, Shende, Bhoie, Dhenge, Tejare, Bandobhnje, Waghaye, Trichkule, Baraskar, Khawas, Bhuse, etc.[78] The Anthropological Survey of India states in 2003 that the Jhade boys and girls have access to formal education who mostly go on to attain high school education.[80] The Survey also states that the community also has access to modern day amenities like electricity, health centres, motorable roads, public transport, post offices, drinking water and fair price shops of the Indian Public Distribution System.[80] Some family names of the Bowne recorded in Russel and Lal in 1916 with their English meanings are: Kantode (broken ear), Nagtode (broken nose), Dukkarmare (a pig killer), Titarmare (pigeon killer), Ghodmare (horse killer), Waghmare (tiger killer), Gadhe (a donkey), and Lute (a plunderer).[51][j]Khaire

The Kunbi Khaire derive their name from the local name for catechu, Khair, which the community has traditionally cultivated as an occupation.[80] The home districts of the community are the Chandrapur and Gadchiroli districts and in these districts they are also known as Khedule Kunbi.[82] The community is endogamous and practices arranged marriages, the typical age of marriage for men and women is between 20–25 and 18–22 respectively.[83] Cremation of the dead is the norm, burial is an exception for the economically disadvantaged who cannot afford cremation.[84] Kunbi Khaire men are occasional non-vegetarians whereas the women are vegetarian.[46] Borkte, Kukorkar, Lambade, Tiwade, Thakur, Chatur, Pal, Dhake, Elule, Sangre, Tangre, Timare are only a few of the Khaire surnames from a long list.[46] Important festivals observed by the community are Dussera, Diwali, Holi and Ganeshchaturthi.[85] Traditional places of pilgrimage are Pandharpur, Nasik, Ramtek and Tuljapur.[85]

The use of the traditional jati panchayats have been discontinued by the Khaire community for a long time and the community now makes use of the gram panchayat while still consulting community elders for some social disputes.[85] The Anthropological Survey of India states in 2003 that the Khaire boys and girls have access to formal education who mostly go on to attain high school education, and sometimes higher when conditions are favourable.[86] Drop out rates for girls are higher due to social reasons.[86] The Survey also states that the community also has access to modern day amenities of electricity, heath centres, motorable roads, public transport, post offices, drinking water and fair price shops of the Indian Public Distribution System.[86]

Leva or Leva Patil

The Leva or Lewa are synonymous with the Lewa Patil, the suffix, "Patil", being a feudal title.[3] The community does not have an oral tradition of their origin or migration but they generally accept that they have migrated from Gujarat to the Vidharba region via Nimar which is now in Madhya Pradesh.[3] The community is associated with two other communities from Gujarat, the Lewa and the Lewa Patidar, the former are a well known community and the latter are sometimes referred to as their parental group, however, the Kunbi Leva Patil of Maharashtra have roots which are long established in the Kunbi community of Maharashtra.[3] The community perceives their distribution to be in 72 villages in the Jalgaon and Buldhana districts.[3] The Lewa Patil are numerically, economically and educationally superior in some of the multi-ethnic villages of the Buldhana and Jalgaon district.[3] Nuclear families are replacing the traditional extended family system due to a changing economy and due to an increasing number of conflicts over property inheritance.[44] Cremation of the dead is the norm, burial the exception for the very young (up to three to four months age).[87] There is no distinctive attire of the Leva community – they follow local fashion trends.[88] On very rare occasions, older Leva men wear a Gujarati style, boat shaped topi or hat made from black or brown silk.[88] Some of the common Leva surnames are Warade (Deshmukh), Narkhede, Kharche, Supe, Borle, Panchpande, Kolte, etc.[88] Dowry is practiced in the Leva community and the amount is negotiable.[44] The attitude towards formal education is positive though Leva girl students drop out of school earlier due to social conditions.[89]

Lonari

Main article: LonariThe Lonari Kunbis are regarded as one of the established cultivating communities in Maharashtra.[90] The Lonari are presently located in the eastern part of the Vidharbha region and in the adjoining districts of Madhya Pradesh.[49] The name of the community comes from Lonar lake in the Mehkar-Chikhli taluka of the Buldhana district where their original occupation was salt making from the salt lake.[64][49] They migrated from the Lonar lake region and eventually arrived in present-day Maharashtra.[49] The oral tradition of the community contains an elaborate story of their migration. The tradition states that the community migrated first to Aurgangabad from their original place of origin in the Lucknow district of Uttar Pradesh then to Buldana and finally to their current locations in the Amravati and Betul districts of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh respectively.[49] In the two tehsils of Multai and Warud in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashra respectively, the Lonari Kunbi are also known as Deshmukhs and Kumbhares.[49] The Lonari now rely on the gram panchayats under the state government as changes in the sociopolitical landscape have caused the influence of the traditional caste council to diminish.[90] Monogamy and adult marriages are the norm but the practice of marriage to a woman of the same surname (referred to as hargote) is not allowed.[91] According to the Lonari Kunbi community, they do not engage in the practice of dowry[91] The Lonari Kunbis follow the joint family system but the restrictions on land-owning for agriculture under the Land Revenue Act and the improved educational status of the newer generations is a cause of formation of nuclear families.[92] A large number of the community members depend on revenue from agriculture, either by directly cultivating their own lands or by working as agricultural labour.[90] The Lonari Kunbi community has made much progress since the 1950s but problem of poverty is still prevalent and economic instability is still a concern to members of the community.[93]

Tirole or Tirale

The Kunbi Tirole are an agricultural community found in the Khandesh region of Maharashtra.[94] The community believe that they are Rajputs who migrated from Rajasthan as a result of a general migration of the tribes of Rajputana.[94][64] Older ethnographic accounts note that a large scale migration of the community occurred from Rajasthan to Maharashtra in the eighteenth century under the reign of Raghuji Bhonsle.[94] The community enjoys a high social status amongst the other agricultural communities.[94] One reason for their high social status is the fact that some families of this community were chosen to collect revenue in the days of the Maratha Empire.[94] Two separate etymologies exist for the community name.[94] One states that the community is named after the place of their origin, Therol, in Rajasthan. The other states that the community gets its name from their original occupation of Til or sesame cultivation.[94][64] Compared with the other Kunbi communities, the Tirole are numerically superior to all and their home districts are Nagpur, Wardha, Amravati and Yeotmal districts.[94] Although occasional non-vegetarian men are found in the community, the community is mainly and traditionally vegetarian.[94]

Based on evidence from an old Marathi document, Karve concludes that the Tirole Kunbi differ significantly from the Kubis to the west of Nagpur and that they did not formerly claim to be Kshatriyas.[95] This claim is in contradiction with Russell and Lal who suggests that the Tirole claim to be Rajputs.[64] Based on the contradiction with Russell, G. S Ghurye states that Karve's statement is either esoteric or wrong.[96] Russell and Lal record the population of the Tirole at seventy thousand in 1880 amongst a total of three hundred and fifty thousand Khandeshi Kunbis.[97]

Some family names of the Tirale recorded in Russel and Lal in 1916 with their English meanings are: Kolhe (jackal), Wankhede (a village name), Kadu (bitter), Jagtap (famous), Kadam (a tree), Meghe (a cloud), Lohekari (iron worker), Ughde (exposed), Shinde (a palm tree), Hagre (one who suffers from diarrhea), Aglawe (an incendiary), Kalamkar (a writer), Wani (trader) and Sutar (carpenter).[51]

Another agricultural community, the Kunbi Ghatole, claim that they are the same as the Tirole.[94]

Kunbi communities in other states

The 1885 Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia described the Kunbi as "though quiet and unpretending, are a robust, sturdy, independent agricultural people... though their institutitions are less democratic than those of the Jat and Rajput..." The author also noted that the Hyderabad Kunbi of the period were known to be "wholly illiterate." The 1881 Census of India stated that the Kunbi in all of India numbered 5,388,487.[13][dubious ]

In Gujarat, Kunbi communities are found in the Dangs, Surat and Valsad districts.[12] More recently, in 2003, Singh and Lal, have described the Kunbi of Gujarat as being non-vegetarian and consumers of alcoholic drinks such as mohua. That community believes itself to be of a higher status than some other local groups due to the type of meat which they consume (for example, they believe that the Warlis eat rats, and other groups eat beef). The community practices monogamous endogamy and marriage of cross cousins is acceptable, as is remarriage by widows. Divorce is permitted and the practice of marriage around the age of 10 – 12 years has been abandoned. Their dead are cremated.[98]

A population of Kunbi (also locally called Kurumbi) is also found in Goa, where they are believed to be descendants of the area's aboriginal inhabitants. They are largely poor agriculturalists,[citation needed] though some of the oldest known landowners in Goa were of this class, and claimed for themselves the Vaishya (merchant) varna.[99] According to the leaders of the Uttara Kannada district Kunabi Samaj Seva Sangh, the population of their community in the region is 75,000.[100]

Politics

The Kunbis along with the two other backward communities, the Teli and the Mali play a major role in the politics of the Vidharbha region of Maharashtra.[101] The three groups together make up to 50% of the electorate and are known to influence election outcomes.[101] The Kunbis, being landlords, hold the upper-hand in the politics of the region and can decide the outcome of at least 22 seats since they are dominant in every single village of the region.[101] The Kunbis, who are known to have a more tolerant attitude and are more secular than the Telis, prefer the Congress party which has caused the party to hold a dominant position in the region for several decades.[101] However in the last decade or so, the Congress has ignored the Kunbis and other parties like the BJP and the Shiv Sena have seized the opportunity by giving more opportunities to Kunbi candidates in elections.[101]

The Kunbi vote is frequently said to be the deciding factor in elections. In the 2009 elections, resentment of the Kunbis towards the Congress candidate Wamanrao Kasawar was said to have been benefiting Sanjay Derkar, the independent NCP rebel candidate, in a triangular contest which also included Shiv Sena's Vishvas Nandekar.[102] In the 2004 MLA elections in Murbad, the Kunbi vote was said to be the deciding vote in favour of Digambar Vishe, a BJP candidate belonging to the Kunbi community.[103]

The former prime minister of India, P. V. Narasimha Rao who consistently won elections from the Ramtek constituency was forced to run for elections from Andhra Pradesh after polling just 34,000 votes in 1989 to a relatively low key Janata Dal candidate, Pandurang Hajare.[104] Since them Ramtek has elected a candidate belonging to the Kunbi-Maratha community with consistency.[104]

Nationalist Congress Party

According to the Indian Express, soon after its inception in May 1999, the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) was working hard to get rid of its "Kunbi Only" image because Sharad Pawar found, after breaking away from the Congress, that it was not possible to win elections with just the Kunbi vote.[105] To attract the non-Kunbi OBC vote, which was estimated to form 40 percent of the electorate, Pawar recruited Chhagan Bhujbal, a Mali, and Pandurang Hajare, a Teli.[105] Even though Pawar recruited other Telis like Pandurang Dhole, the Indian Express wondered if it would be enough to counter the age-old and keen Kunbi versus Teli rivalry.[105] However a closer look at local and regional heavyweight leaders in the NCP revealed that almost all belonged to the Kunbi community.[105] In 2009, the NCP president Sharad Pawar chose Anil Deshmukh over Rajendra Shingane as a party candidate from the Vidharbha region because he represents the huge Kunbi-Marathi community in the region.[106]

OBC vote politics

According to the leading contemporary commentator on religious and political violence in India, Thomas Blom Hansen, one reason for the failure of political parties to consolidate the OBC votes in one block in Maharashtra, unlike in northern India, despite calls for "Kunbi-zation" of the Maratha caste, was the fact that Maharashtra had, as early as 1967, identified 183 communities as "educationally backward classes".[107] By 1978 there were 199 communities in this category and the government implemented a policy of reserving 10 percent of educational seats and government jobs for these.[107] The official data used by the government for the definition of the Maratha-Kunbi castes puts them between 30 to 40 percent depending on whether a narrow or an inclusive definition of the caste is used.[108] This causes the percentage of OBCs to vary between 29 to 38 percent of the population. It is critically important for the politicians of the state to ensure a narrow definition of OBC and maximize the Maratha representation.[108] Thus the Maratha Mahasangha (All-Maratha Federation), fearing that the Mandal Commission would divide the Maratha-Kunbis in to Kunbis and high Marathas, took an anti-Mandal stance and tried to attract marginalized Maratha-Kunbis by propagating martial and chauvinistic myths which in turn stigmatized the Muslims and Dalits.[108] While the organization never received success outside of Mumbai, it showed that political leaders were willing to counter the rising OBC assertiveness.[108]

Forgery of caste certificates

There are several communities in Maharashtra that have been trying to pass themselves off as a depressed community in order to reap the benefits of the reservation.[18] An issue of candidates of the Maratha caste, a non-backward caste, running for elections in wards reserved for OBC candidates got centre stage attention in the 2007 civic polls after the Maharashtra state government amended the OBC list on June 1, 2004 to retain the Kunbis and also include Kunbi-Marathas in the list.[109] In 2010, the independent corporator, Malan Bhintade, who claimed to be Kunbi-Maratha but was actually later found to be of Maratha caste, lost her membership of the Pune Municipal Corporation after it was established that she had submitted a false caste certificate claiming to be Kunbi-Maratha thus qualifying to run for elections in wards reserved for OBC candidates.[109] Subsequently all candidates who lost to Kunbi-Maratha candidates registered complaints against their opponents claiming falsification of certificates.[109] A similar case of forgery of a caste certificate was reported in 2003 when the former Shiv Sena corporator, Geeta Gore, was sent to jail for falsely claiming to be a Kunbi Maratha.[110] Geeta Gore had won in elections from ward 18 of Andheri (west) by claiming to be a member of the Kunbi-Maratha caste.[110]

Reservation in politics

Ramdas Athvale, the president of the Republican Party of India (Athvale) advocated a caste based census in 2010.[111] He claimed that many members of the Maratha caste in Maharashtra had converted to the Kunbi caste and such conversions and changes in the demographics of backward class populations can only be gauged by a caste-based census.[111] While welcoming the decision of the Union Cabinet to conduct a caste based census in 2011, the OBC leader Gopinath Munde said that 50% of the Kunbi Marathas were in the OBC category and that he supported reservation for the Maratha community in education and employment in the private sector but not in politics.[112] Rajendra Vora stated in 2009 that even though the Marathas form 31 percent of the population, they have controlled 50 percent of the seats in the Maharashtra legislative assembly.[113] In a paper dedicated to the topic, “Maharashtra: Virtual reservation for Marathas”, he claims that the Maratha-Kunbi community has de facto reservation in the Maharashtra legislative assembly.[113] In January 2009, leaders of backward class community met with the Deputy Chief Minister of Maharashtra to persuade him to keep the Marathas out of the OBC quota suggesting that since the Marathas are a part of the Kunbi community and that the Kunbis already have a quota, there is no need for the Marathas to be included as well.[114]

Inter-caste issues

In 2006, four members of a Dalit family with the surname "Bhotmange" were murdered after being tortured by members of the Kunbi caste from the Khairlanji village in the Bhandara district.[115] Two female members of the same family were paraded naked in the village and then raped.[115] The Nagpur bench of the Mumbai High Court has sentenced eight villagers to life imprisonment, declaring the killings were motivated by revenge and not racism or casteism.[116] An appeal against the High Court judgement to have the crime declared as casteism is still pending in the Supreme Court of India.[117]

The Times of India reported in February 2011 that an honour killing of a Dalit man and Kunbi woman was suspected in Murbad of Thane district.[118] Later in September of the same year, a 20 year old Dalit woman alleged that she was raped by a Someshwar Baburao Kuthe of the Kunbi caste in the Sarandi (Bujaruk) village of Lakhandur taluka.[119] The local police registered an offense under section 376, 506 of IPC and under section 3(1) 12 of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.[119]

Marathas claiming OBC status through Kunbi affiliation

A representative of the Maratha community, Vinayak Mete, stated that the Maratha caste has roots in the Kunbi caste while making a case for extending the benefits of reservation to the Marathas.[120] Mete also noted that the majority of the suicides by farmers in Maharashtra were in the Kunbi-Maratha community.[120] According to Maratha leaders, the OBC status accorded to the Kunbis should be extended to the Marathas since Kunbis are Marathas.[121] However Professor Goswami quotes the Khatri Commission and the Nagpur and Aurangabad benches of the Bombay High Court to reject the notion that the Kunbis are Marathas.[121][k] In April 2005 the Supreme Court of India ruled that the Marathas are not a part of the Kunbi community.[121]

See also

- List of Kunbi people

- Kunabi Sena

- Kudumbi

External links

Footnotes

- ^ In Hinduism, communities are divided into four main social classes, also known as Varna in Sanskrit. Each class is further sub-divided into a multitude of castes. The term 'Caste Hindu' is used to refer to these four main classes.[6] The Dalits (also known as Mahars and Harijans)[6] were traditionally outside of caste system and can now be said to form a fifth group of castes. The first three Varnas in the hierarchy are said to be dvija (twice-born). They are called twice born on account of their education and these three castes are allowed to wear the sacred thread. These three castes are called the Brahmins, the Kshatriyas and the Vaisyas. The traditional caste-based occupations are priesthood for the Brahmins, ruler or warrior for the Kshatriyas and businessman or farmer for the Vaisyas. The fourth caste is called the Shudras and their traditional occupation is that of a labourer or a servant. While this is the general scheme all over India, it is difficult to fit all modern facts in to it.[7] These traditional social and religious divisions in the caste system have lost their significance for many contemporary Indians except for marriage alliances.[6] The traditional pre-British, and pre-modern, Indian society, while stationary, afforded very limited caste mobility to those from non-elite castes who could successfully wage warfare against (and seize power from) a weak ruler, or bring wooded areas under the plough to establish independent kingdoms. According to M. N. Srinivas, "Political fluidity in pre-British India was in the last analysis the product of a pre-modern technology and institutional system. Large kingdoms could not be ruled effectively in the absence railways, post and telegraph, paper and printing, good roads, and modern arms and techniques of warfare.".[8]

- ^ The Indian Constitution of 26 January 1950 outlawed untouchability and caste discrimination.[9] The constitution gives generous privileges to the backward castes in an effort to redress injustice over the ages.[10]

- ^ Eaton, 2005. Quote: "Rather than claim that he (Tukaram) had no caste – a practical impossibility in his day – he affirmed his identity as a Kunbi, Maharashtra's dominant agrarian community (within the sudra category)."[11]

- ^ The Sholapur District Gazetter of 1881 makes this statement about the Kunbis: "Kunbis are said to be bastards or akarmashe Marathas the offspring of a Maratha by a Maratha Woman not his wife."[22]

- ^ The other powerful Maratha dynasty, the Holkars, were of Dhangar or shepherd origin.[26]

- ^ This elite group of pure, assalll or true Marathas claimed to be a group of 96 clans. They attempted to link themselves to the four Kshatriya lineages, Solar, Lunar, Brahma and Shesh via the Rajputs of north India. However the list of the 96 clans is highly controversial and there seems to be no consensus on who is in or out of the elite group of 96.[32]

- ^ The current heir in the line of the Shindes is Jyotiraditya Scindia, a member of the Indian parliament.

- ^ "The local Brahmans had denied the Marathas or Kunbi peasantry any Kshatriya status, Phule argued, and Shivaji therefore relied more on the Prabhus, a Kshatriya literate community of scribes, for his administration. According to this interpretation, Shivaji opposed the local power of Brahmans in the villages and tried to establish a more direct link between king and subjects. This manifested itself, for instance, in his making privileges and landholdings accessible to lower-caste Kunbis, who in various ways had distinguished themselves in combat or services to the king."[54]

- ^ Immigrant communities of Maharashtra include the Bene Israeli Jews, Perik, Balija, Deccani Sikhs, Gadia, Lohar, Bahubalia, etc.[19]

- ^ "Surname suggest identity, status, and level of aspiration. Maharashtra is a paradise for hunters of surnames. First there is the ecology which explains presence of totemestic. names, after plants, birds animals, trees. Even though totemism is at a discount, environmentalists today are interested in ecological links In fact our study shows that Maratha and cognate groups, being autochthones, have a larger and more complex range of surnames linked with environment, history and culture. Surnames with the names of villages suffixed with kar is mostly found in Maharashtra...Titles have become surnames (kulkarni, deshpande, joshi, etc.) The occupational diversification among the Parsis shows through surnames such as bandukwala, daruwala, sopariwala, etc."[81]

- ^ The Bombay High Court ruled in October 2003 in Jagannath Hole’s case that to accept Marathas as belonging to the Kunbi community would result in “nothing short of a social absurdity.”[121]

Notes

- ^ Lele 1981, p. 56 Quote: "Village studies often mention the dominance of the elite Marathas and their refusal to accept non-elite Marathas such as the Kunbis into their kinship structure (Ghurye, 1960; Karve and Damle, 1963)."

- ^ Gadgil & Guha 1993, p. 84 Quote: "For instance, in western Maharashtra the Rigvedic Deshastha Brahmans are genetically closer to the local Shudra Kunbi castes than to the Chitpavan Konkanastha Brahmans (Karve and Malhotra 1968)."

- ^ a b c d e f Dhar 2004, p. 1218.

- ^ a b Singh, Lal & Anthropological Survey of India 2003, p. 734.

- ^ a b c d e Dhar 2004, pp. 1179–1239.

- ^ a b c Lamb 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Farquhar 2008, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Srinivas 2007, pp. 189–193.

- ^ Rajagopal 2007.

- ^ Datta-Ray 2005.

- ^ Eaton 2005, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d e Singh, Lal & Anthropological Survey of India 2003, p. 731.

- ^ a b c Balfour 1885, p. 626.

- ^ a b c d e Dhar 2004, p. 1199.

- ^ Singh, p. 1199.

- ^ a b Russell & Lal 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Ghurye 2008, p. 31.

- ^ a b Singh 2004, p. xliii.

- ^ a b c Singh 2004, p. xliv.

- ^ Singh 2004, p. 22.

- ^ a b Russell & Lal 1995, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e Ghurye 2008, p. 201.

- ^ Bhattacharya 1896, p. 270.

- ^ Government of India 1867, p. 36.

- ^ The Hindu 2006, p. 1.

- ^ a b c O'Hanlon 2002, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e O'Hanlon 2002, p. 16.

- ^ a b Eaton 2005, p. 190-1.

- ^ Gordon 1993, p. 15.

- ^ a b Eaton 2005, p. 191.

- ^ O'Hanlon 2002, p. 16-17.

- ^ a b c d e O'Hanlon 2002, p. 17.

- ^ a b Jadhav 2006, p. 2.

- ^ a b O'Hanlon 2002, p. 38.

- ^ a b c O'Hanlon 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Singh 2004, p. xl.

- ^ a b Jadhav 2006, p. 1.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Ghurye 2008, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d Dhar 2004, p. 1180.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1186.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dhar 2004, p. 1193.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1200.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1220.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1207.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1213.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1235.

- ^ Singh, Lal & Anthropological Survey of India 2003, p. 1235.

- ^ a b c d e f Dhar 2004, p. 1224.

- ^ Singh, Lal & Anthropological Survey of India 2003, pp. 734–5.

- ^ a b c Russell & Lal 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Bary & Bary 1988, p. 681.

- ^ Naik 2003, p. 358.

- ^ Hansen 2005, pp. 26–7.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1183.

- ^ a b c d Dhar 2004, p. 1179.

- ^ Ghurye 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Russell & Lal 1916, p. 359.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1182-3.

- ^ a b Dhar 2004, p. 1182.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1181.

- ^ Russell & Lal 1995, pp. 40–1.

- ^ a b c d e Dhar 2004, p. 1185.

- ^ a b c d e Russell & Lal 1995, p. 19.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1185-6.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1190.

- ^ Gaikwad 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dhar 2004, p. 1192.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1196-7.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1195.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1196.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1197.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1199-1200.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1200-02.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1203.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1202.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dhar 2004, p. 1206.

- ^ a b Singh, p. 1206.

- ^ a b Dhar 2004, p. 1210.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1211.

- ^ Singh 2004, p. xlv–xlvi.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1212.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1213-5.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1215.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1216.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1217.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1222.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1219.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1223.

- ^ a b c Dhar 2004, p. 1230.

- ^ a b Dhar 2004, p. 1226.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1227.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1232.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dhar 2004, p. 1233.

- ^ Ghurye 2008, p. 202.

- ^ Ghurye 2008, p. 202-3.

- ^ Ghurye 2008, p. 203.

- ^ Singh, Lal & Anthropological Survey of India 2003, p. 731-733.

- ^ Dhar 2004, p. 1396.

- ^ The Hindu 2011, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Bhagwat 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Abraham 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Ballal 2004.

- ^ a b Roy 2009, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Haque 1999.

- ^ Marpakwar 2009, p. 1.

- ^ a b Hansen 2001, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Hansen 2001, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Times News Network 2010.

- ^ a b Times News Network 2003.

- ^ a b TNN 2010.

- ^ The Hindu 2010.

- ^ a b Menon 2009a.

- ^ Ghoge 2009.

- ^ a b Balakrishnan 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Hattangadi 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Times News Network 2011.

- ^ Gupta 2011.

- ^ a b TNN 2011.

- ^ a b Menon 2008, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Menon 2009b, p. 1.

References

- Abraham, T. O (October 22, 2009), Yavatmal administration geared up for vote count, The Times of India, http://m.timesofindia.com/PDATOI/articleshow/5145855.cms, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Agrawal, Arun; Sivaramakrishnan, K. (2000), Agrarian environments: resources, representations, and rule in India, Duke University Press, p. 235, ISBN 978-0-8223-2574-1, http://books.google.com/books?id=B0doGs2t6aEC&pg=PA235, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Balakrishnan, S (29 July 2010), Khairlanji survivor to move apex court over HC verdict, The Times of India, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-07-29/mumbai/28288134_1_khairlanji-massacre-appeal-move-apex-court, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Balakrishnan, S, Khairlanji survivor to move apex court over HC verdict, The Times of India, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-07-29/mumbai/28288134_1_khairlanji-massacre-appeal-move-apex-court, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Balfour, Edward (1885), The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial Industrial, and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures, Bernard Quaritch, http://books.google.com/books?id=3U0OAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA626

- Ballal, Milind (October 8, 2004), What do Sena, Cong share in Thane?, The Times of India, http://m.timesofindia.com/PDATOI/articleshow/877580.cms, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Bandyopādhyāẏa, Śekhara (2004), From Plassey to partition: a history of modern India, Orient Blackswan, pp. 197–, ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2, http://books.google.com/books?id=0oVra0ulQ3QC&pg=PA197, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Barendse, R. J. (2009), Arabian Seas 1700–1763: The Western Indian Ocean in the eighteenth century, BRILL, p. 914, ISBN 978-90-04-17661-4, http://books.google.com/books?id=WyBZ7wVBdtoC&pg=PA914, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Bary, S.N.H.W.T.D.; Bary, W.T.D. (1988), Sources of Indian Tradition, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd), ISBN 9788120804685, http://books.google.com/books?id=MBWzV-TRXzkC, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Basu, Pratyusha (2009), Villages, women, and the success of dairy cooperatives in India: making place for rural development, Cambria Press, pp. 53–, ISBN 978-1-60497-625-0, http://books.google.com/books?id=zJxY9IWzGewC&pg=PA53, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Bayly, C. A. (1989), Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire, Cambridge University Press, p. 29, ISBN 978-0-521-38650-0, http://books.google.com/books?id=fX2zMfWqIzMC&pg=PA29, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Bayly, Susan (2001), Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age, Cambridge University Press, p. 57, ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6, http://books.google.com/books?id=HbAjKR_iHogC&pg=PA57, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Bhagwat, Ramu (Sep 15 2009), Kunbis, Telis have major say in polls in Vidarbha, The Times of India, http://m.timesofindia.com/PDATOI/articleshow/5012033.cms, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Bhattacharya, Jogendra Nath (1896), Hindu castes and sects: an exposition of the origin of the Hindu caste system and the bearing of the sects towards each other and towards other religious systems, Thacker, Spink, pp. 270–, http://books.google.com/books?id=xlpLAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA270, retrieved 13 May 2011

- Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan (2003), The origins of industrial capitalism in India: business strategies and the working classes in Bombay, 1900–1940, Cambridge University Press, p. 221, ISBN 978-0-521-52595-4, http://books.google.com/books?id=ZFa5tb75QUsC&pg=PA221, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Charlesworth, Neil (2002), Peasants and Imperial Rule: Agriculture and Agrarian Society in the Bombay Presidency 1850–1935, Cambridge University Press, p. 11, ISBN 978-0-521-52640-1, http://books.google.com/books?id=jIbRhV00p6AC&pg=PA11, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Chaturvedi, Vinayak (2007), Peasant pasts: history and memory in western India, University of California Press, p. 42, ISBN 978-0-520-25078-9, http://books.google.com/books?id=MzPlZSOjCpsC&pg=PA42, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Chaudhuri, B. B.; Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture; Centre for Studies in Civilizations (Delhi, India) (2008), Peasant history of late pre-colonial and colonial India, Pearson Education India, p. 543, ISBN 978-81-317-1688-5, http://books.google.com/books?id=ljmIJySEm4UC&pg=PA543, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Datta-Ray, Sunanda K (13 May 2005), India: An international spotlight on the caste system, The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/12/opinion/12iht-eddattaray.html, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Dhar, P. (2004), Bhanu, B.V.; Bhatnagar, B.R.; Bose, D.K. et al., eds., People of India: Maharashtra, People of India, 2, Anthropological Survey of India, ISBN 8179911012, http://books.google.com/books?id=BsBEgVa804IC, retrieved 5 October 2011

- Eaton, Richard M (2005), A social history of the Deccan, 1300–1761: eight Indian lives, The new Cambridge history of India, 8, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521254847, http://books.google.com/books?id=DNNgdBWoYKoC

- Farquhar, J. N (2008), The Crown of Hinduism, READ BOOKS, ISBN 9781443723978, http://books.google.com/?id=apnn55kIKo8C, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Gadgil, Madhav; Guha, Ramachandra (1993), This fissured land: an ecological history of India, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-08296-0, http://books.google.com/books?id=Jmr9n7aoRR4C&pg=PA84, retrieved 10 October 2011

- Guha, Ranajit (1999), Elementary aspects of peasant insurgency in colonial India, Duke University Press, p. 141, ISBN 978-0-8223-2348-8, http://books.google.com/books?id=y5SrnXC-HNcC&pg=PA141, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Sumit Guha (2006), Environment and Ethnicity in India, 1200–1991, Cambridge University Press, p. 196, ISBN 978-0-521-02870-7, http://books.google.com/books?id=GSa5blriOYcC&pg=PA196, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Gaikwad, Rahi (25 September 2009), Shiv Sena has an edge in Vidarbha region, The Hindu, http://www.thehindu.com/news/states/other-states/article25212.ece, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Gaikwad, Rahi (April 28, 2009), A tale of four constituencies, The Hindu, http://blogs.thehindu.com/elections2009/?p=2237, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Gaikwad, Rahi (July 29, 2010), Khairlanji case set to go to Supreme Court, The Hindu, http://www.hindu.com/2010/07/29/stories/2010072962281400.htm, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Ghoge, Ketaki (1 February 2009), OBC leaders meet Bhujbal, Hindustan Times, http://www.hindustantimes.com/StoryPage/Print/373302.aspx, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Ghurye, G.S. (2008) [1932], Caste and race in India, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 9788171542055, http://books.google.com/books?id=nWkjsvf6_vsC

- Gidwani, Vinay K. (2008), Capital, interrupted: agrarian development and the politics of work in India, U of Minnesota Press, p. 274, ISBN 978-0-8166-4959-4, http://books.google.com/books?id=Ek9Sl2kk3f4C&pg=PA274, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Gordon, Stewart (1993), The Marathas 1600–1818, New Cambridge history of India, 4, Cambridge University, ISBN 9780521268837, LCCN 92016525, http://books.google.com/books?id=iHK-BhVXOU4C

- Government of India (1867), Various census of India, pp. 36–, http://books.google.com/books?id=2v8IAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA36, retrieved 13 May 2011

- Gupta, Pradeep (24 February 2011), Tension grips Murbad over honour killing, The Times of India, http://lite.epaper.timesofindia.com/mobile.aspx?article=yes&pageid=7&edlabel=TOIM&mydateHid=24-02-2011&pubname=&edname=&articleid=Ar00708&format=&publabel=TOI, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Hansen, Thomas Blom (2001), Wages of violence: naming and identity in postcolonial Bombay, (Ethnographic Explorations of the Postcolonial State), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08840-2, LCCN 2001095813, http://books.google.com/books?id=-y3iNt0djbQC, retrieved 22 October 2011

- Hansen, Thomas Blom (2005), Violence in urban India: identity politics, 'Mumbai', and the postcolonial city, Ethnographic Explorations of the Postcolonial State, Permanent Black, ISBN 9788178241203, LCCN 2001095813, http://books.google.com/books?id=iRAj9NnMdYgC

- Haque, MOIZ MANNAN (August 4, 1999), NCP desperate to woo non-Kunbi OBCs, The Indian Express, http://www.indianexpress.com/Storyold/113414/, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Hardikar, Jaideep (June 15, 2010), Khairlanji judgment adjourned till July 14, DNA, http://www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report_khairlanji-judgment-adjourned-till-july-14_1396658, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Krishan, Shri (2005), Political mobilization and identity in western India, 1934–47, SAGE, p. 207, ISBN 978-0-7619-3342-7, http://books.google.com/books?id=Pn5m7KFhgVEC&pg=PA207, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Hattangadi, Shekhar (25 August 2010), In the Khairlanji case, justice is not seen to be done, DNA, http://www.dnaindia.com/opinion/main-article_in-the-khairlanji-case-justice-is-not-seen-to-be-done_1428322, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Jadhav, Vishal (2006), Role of Elite Politics in the Employment Guarantee Scheme, Samaj Prabodhan Patrika (Marathi Journal), http://www2.ids.ac.uk/gdr/cfs/pdfs/vishalmarathiart.pdf, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Jaffrelot, Christophe, Dr Ambedkar and untouchability: analysing and fighting caste, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 9781850654490, http://books.google.com/books?id=KIIJkaJo4z4C, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003), India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India, Columbia University Press, p. 146, ISBN 978-0-231-12786-8, http://books.google.com/books?id=qJZp5tDuY-gC&pg=PA146, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Kamat, Prakash (22 October 2010), Material benefits, The Hindu, http://www.thehindu.com/life-and-style/fashion/article842943.ece, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Lamb, Ramdas (2002), Rapt in the name: the Ramnamis, Ramnam, and untouchable religion in Central India, State University of New York Press, ISBN 9780791453858, LCCN 2002070695, http://books.google.com/books?id=STw9LQtx89oC

- Lele, Jayant (1981), Elite pluralism and class rule: political development in Maharashtra, India, Toronto and London: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-5440-1, http://books.google.com/books?id=C24mAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA56, retrieved 10 October 2011

- Marpakwar, Prafulla (September 11, 2009), Valse-Patil off ministers list,may be up for speaker, The Times of India, http://lite.epaper.timesofindia.com/mobile.aspx?article=yes&pageid=5&edlabel=TOIPU&mydateHid=09-11-2009&pubname=&edname=&articleid=Ar00501&format=&publabel=TOI, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Menon, Meena (April 19, 2009), Sugar power, The Hindu, http://blogs.thehindu.com/delhi/?p=19389, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Menon, Meena (February 12, 2009), The Maratha question set to come to a head, The Hindu, http://blogs.thehindu.com/delhi/?p=14004, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Menon, Meena (September 24, 2008), Deshmukh keen to consolidate Maratha votes, The Hindu, http://blogs.thehindu.com/delhi/?p=2766, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Mitta, Manoj (25 July 2010), The Buddha is not SMILING, The Times of India, http://lite.epaper.timesofindia.com/mobile.aspx?article=yes&pageid=21&edlabel=TOIM&mydateHid=25-07-2010&pubname=&edname=&articleid=Ar02100&format=&publabel=TOI, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Naik, C.D. (2003), Thoughts and philosophy of Doctor B.R. Ambedkar, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 9788176254182, LCCN 2003323197, http://books.google.com/books?id=0Bo0Rjlp-0QC

- O'Hanlon, Rosalind (2002), Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521523080series=Cambridge South Asian Studies, http://books.google.com/books?id=5kMrsTj1NeYC

- Pinch, William R. (1996), Peasants and monks in British India, University of California Press, p. 90, ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6, http://books.google.com/books?id=uEP-ceGYsnYC&pg=PA90, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Press Trust of India (14 April 2004), Ambedkar's grandson eyes for hattrick in Akola, The Hindustan Times, http://www.hindustantimes.com/Ambedkar-s-grandson-eyes-for-hattrick-in-Akola/Article1-14865.aspx, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Press Trust of India (July 28, 2010), Bhotmange to move SC in Khairlanji murders case

- Rajagopal, Balakrishnan (18 August 2007), The caste system – India's apartheid?, Chennai, India: The Hindu, http://www.hindu.com/2007/08/18/stories/2007081856301200.htm, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Rege, Sharmila (2006), Writing caste, writing gender: reading Dalit women's testimonios, Zubaan, p. 17, ISBN 978-81-89013-01-1, http://books.google.com/books?id=Msaki69NQHsC&pg=PA17, retrieved 26 October 2011

- Roy, Ashish (March 15, 2009), Ramtek voters in tepid mood, The Times of India, http://www1.m.timesofindia.com/PDATOI/articleshow/4265463.cms, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Russell, R. V.; Lal, R. B. H. (1995) [1916], The tribes and castes of the central provinces of India, 1, Asian Educational Services, p. 17, ISBN 9788120608337, http://books.google.com/books?id=76c1VSYnPE0C&pg=PA17

- S., Bageshree (April 29, 2011), Reclaiming the radical B.R. Ambedkar, The Hindu, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-karnataka/article1820664.ece, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Sainath, P. (April 17, 2009), It’s cars versus ‘karyakarthas’ in Bhandara-Gondiya, The Hindu, http://blogs.thehindu.com/delhi/?p=19206, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Singh, Kumar Suresh (2004), Bhanu, B.V.; Bhatnagar, B.R.; Bose, D.K. et al., eds., People of India: Maharashtra, People of India, 2, Anthropological Survey of India, ISBN 8179911012, http://books.google.com/books?id=BsBEgVa804IC, retrieved 5 October 2011

- Singh, Kumar Suresh; Lal, R. B; Anthropological Survey of India (2003), Gujarat, People of India, Anthropological Survey of India, ISBN 9788179911044, http://books.google.com/books?id=d8yFaNRcYcsC, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Srinivas, M. N (2007), "Mobility in the caste system", in Cohn, Bernard S; Singer, Milton, Structure and Change in Indian Society, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 9780202361383, http://books.google.com/?id=_g-_r-9Oa_sC, retrieved 5 October 2010

- The Hindu (January 7, 2006), "Central nod for OBC list modification", The Hindu, http://www.hindu.com/2006/01/07/stories/2006010706381200.htm, retrieved 2011-10-05

- The Hindu (May 6, 2011), Meeting of ‘Kunabis' today, The Hindu, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-karnataka/article1995942.ece, retrieved October 5, 2011

- The Hindu (September 11, 2010), OBC leaders hail caste census decision, The Hindu, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/article626567.ece, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Times News Network (10 June 2010), PMC corporator loses membership, The Times of India, http://lite.epaper.timesofindia.com/mobile.aspx?article=yes&pageid=3&edlabel=TOIPU&mydateHid=10-06-2010&pubname=&edname=&articleid=Ar00303&format=&publabel=TOI, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Times News Network (15 May 2003), Ex-corporator remanded to police custody, The Times of India, http://m.timesofindia.com/PDATOI/articleshow/46406108.cms, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Times News Network (July 26, 2011), Khairlanji massacre survivor Bhotmange denies remarriage, The Times of India, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-07-26/nagpur/29816089_1_khairlanji-massacre-bhaiyyalal-bhotmange-bhandara-district

- TNN (20 September 2011), 20-year-old woman raped, The Times of India, http://www1.m.timesofindia.com/PDATOI/articleshow/10046681.cms, retrieved October 5, 2011

- TNN (March 5, 2010), Athavale for caste-based census, The Times of India, http://lite.epaper.timesofindia.com/mobile.aspx?article=yes&pageid=3&edlabel=TOIPU&mydateHid=05-04-2010&pubname=&edname=&articleid=Ar00304&format=&publabel=TOI, retrieved October 5, 2011

- Viswanathan, S. (23 August 2010), Khairlanji : the crime and punishment, The HIndu, http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/Readers-Editor/article588045.ece?service=mobile, retrieved October 5, 2011

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.