- Mongolia during Qing rule

-

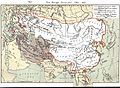

Outer Mongolian 4 aimags and Inner Mongolian 6 leagues ←

1635–1911  →

→

→

→Capital Uliastai[1] Language(s) Mongolian Religion Buddhism

ShamanismGovernment The Qing hierarchy Legislature Khalkha jirum History - The Qing defeats Ligden Khan and receives the imperial authority. 1635 - The surrender of the northern Khalkha. 1691 - Outer Mongolia declares its independence from the Qing Dynasty. December 29, 1911 - Disestablished 1911 History of the Mongols

Before Genghis Khan Khamag Mongol Mongol Empire Khanates - Chagatai Khanate - Golden Horde - Ilkhanate - Yuan Dynasty Northern Yuan Timurid Empire Mughal Empire Crimean Khanate Khanate of Sibir Zunghar Khanate Mongolia during Qing Outer Mongolia (1911-1919) Republic of China (Occupation of Mongolia) Mongolian People's Republic (Outer Mongolia) Modern Mongolia Mengjiang (Inner Mongolia) People's Republic of China (Inner Mongolia) Republic of Buryatia Kalmyk Republic Hazara Mongols Aimak Mongols Timeline edit box Mongolia during Qing rule refers to the period of Qing Dynasty's rule over the Outer Mongolian 4 aimags and Inner Mongolian 6 leagues. The last Khagan Ligdan saw much of his power weakened in his quarrels with the Mongol tribes and was defeated by the Manchus, he died soon afterwards. His son Ejei Khan gave Huang Taiji the imperial authority, ending the Northern Yuan then centered in Inner Mongolia by 1635. However, the Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia retained their independence until they were overrun by the Zunghars in 1690, and they submitted to the Qing Dynasty in 1691.

The Qing Dynasty had ruled Mongolia and Inner Mongolia for over 200 years. During this period Qing rulers established separate administrative structures to govern each region. While the empire maintained firm control in both Inner and Outer Mongolia, the Mongols in Outer Mongolia (which is further from the capital Beijing) enjoyed more degree of autonomy,[2] and also retained own language and culture during this period.[3]

Contents

History

During the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, Outer and Inner Mongolia became part of the Qing Empire. Even before the dynasty began to take control of China proper in 1644, the escapades of Ligden Khan had driven a number of Mongol tribes to ally with the Manchu state. The Manchus conquered a Mongol tribe in the process of war against the Ming. Nurhaci's early relations with the Mongols tribes was mainly an alliance.[4][5] After Ligden's defeat and death his son had to submit to the Manchus, and when the Qing Dynasty was founded, most of what is now called Inner Mongolia already belonged to the new state. The Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia joined in 1691 when their defeat by the Dzungars left them without a chance to remain independent. The Khoshud in Qinghai were conquered in 1723/24. The Dzungars were finally destroyed, and their territory conquered, in 1756/57. The last Mongols to join the empire were the returning Torgud Kalmyks at the Ili in 1771.

From the early years, the Manchus' relations with the neighboring Mongol tribes had been crucial in the dynasty development. Nurhaci had exchanged wives and concubines with the Khalkha Mongols since 1594, and also received titles from them in the early 17th century. He also consolidated his relationship with portions of the Khorchin and Kharachin populations of eastern Mongols. They recognized Nurhaci as Khan, and in return leading lineages of those groups were titled by Nurhaci and married with his extended family. As Nurhaci formally declared independence from the Ming Dynasty and proclaimed the Later Jin Dynasty in 1616, he gave himself a Mongolian-style title, consolidating his claim to the Mongolian traditions of leadership. The banners and other Manchu institutions are examples of productive hybridity, combining "pure" Mongolian elements (such as the script) and Han Chinese elements. Intermarriage with Mongolian noble families had significantly cemented the alliance between the two peoples. Hong Taiji further expanded the marriage alliance policy; he used the marriage ties to draw in more of the twenty-one Inner Mongolian tribes that joined the Manchus alliance. Despite the growing intimacy of Manchu-Mongol ties, Ligdan Khan, the last Khan from the Chakhar, resolutely opposed the growing Manchu power and viewed himself as the legitimate representative of the Mongolian imperial tradition. But after his repeated losses in battle to the Manchus in the 1620s and early 1630s, as well as his own death in 1634, his son eventually submitted to Hong Taiji and the Yuan seal is also said to be handed in to latter, ending the Northern Yuan. The surrendered Mongols as a whole were also enrolled in the banner system. Soon afterwards the Manchus founded the Qing Dynasty and became the ruler of China proper.

The three khans of Khalkha in Outer Mongolia had established close ties with the Qing Dynasty since the reign of Hong Taiji, but had remained effectively self-governing. While Qing rulers had attempted to achieve control over this region, the Oyirods to the west of Khalkha under the leadership of Galdan were also actively making such attempts. After the end of the war against the Three Feudatories, Qing emperor Kangxi was able to turn his attentions to this problem and tried diplomatic negotiations. But Galdan ended up with attacking the Khalkha lands, and Kangxi's responded by personally leading Eight Banner contingents with heavy guns into the field against Galdan's forces, eventually defeating the latter. In the mean time Kangxi organized a congress of the rulers of Khalkha and Inner Mongolia in Duolun in 1691, at which the Khalkha khans formally declared allegiance to him. The war against Galdan essentially brought the Khalkhas to the empire, and the three khans of the Khalkha were formally inducted into the inner circles of the Qing aristocracy by 1694. Thus, by the end of the 17th century the Qing Dynasty had put both Inner and Outer Mongolia under its control.

Governance

For the administration of Mongol regions, a bureau of Mongol affairs was founded, called Monggol jurgan in Manchu. By 1638 it had been renamed to Lifan Yuan, though it is sometimes translated in English as the "Court of Colonial Affairs" or the "Board for the Administration of Outlying Regions". This office reported to the Qing emperor and would eventually be responsible not only for the administration of Inner and Outer Mongolia, but also oversaw the appointments of Ambans in Tibet and Xinjiang, as well as Qing relations with Russia. Apart from day-to-day work, the office also edited its own statutes and a code of law for Outer Mongolia.

Unlike Tibet, Mongolia during the Qing period did not have any overall indigenous government. In Inner Mongolia, the empire maintained its presence through the Qing military forces based along Mongolia's southern and eastern frontiers, and the region was under tight control. In Outer Mongolia, the entire territory was technically under the jurisdiction of the military governor of Uliastai, a post only held by Qing bannermen, although in practice by the beginning of the 19th century the Amban at Urga had general supervision over the eastern part of the region, the tribal domains or aimags of the Tushiyetu Khan and Sechen Khan, in contrast to the domains of the Sayin Noyan Khan and Jasaghtu Khan located in the west, under the supervision of the governor at Uliastai. While the military governor of Uliastai originally had direct jurisdiction over the region around Kobdo in westernmost Outer Mongolia, the region later became an independent administrative post. The Qing government administered both Inner and Outer Mongolia in accordance with the Collected Statutes of the Qing Dynasty (Da Qing Hui Dian) and their precedents. Only in internal disputes the Outer Mongols or the Khalkhas were permitted to settle their differences in accordance with the traditional Khalkha Code. To the Manchus, the Mongol link was martial and military. Originally as "privileged subjects", the Mongols were obligated to assist the Qing court in conquest and suppression of rebellion throughout the empire. Indeed, during much of the dynasty the Qing military power structure drew heavily on Mongol forces to police and expand the empire.

The Mongolian society consisted essentially of two classes, the nobles and the commoners. Every member of the Mongolian nobility held a rank in the Qing aristocracy, and there were ten ranks in total, while only the banner princes ruled with temporal power. In acknowledgement of their subordination to the Qing Dynasty, the banner princes annually presented tributes consisting of specified items to the Emperor. In return, they would receive imperial gifts intended to be at least equal in value to the tribute, and thus the Qing court did not consider the presentation of tribute to be an economic burden to the tributaries. The Mongolian commoners, on the other hand, were for the most part banner subjects who owed tax and service obligations to their banner princes as well as the Qing government. The banner subjects each belonged to a given banner, which they could not legally leave without the permission of the banner princes, who assigned pasturage rights to his subjects as he saw fit, in proportion to the number of adult males rather than in proportion to the amount of livestock that to graze.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Mongolian nomadism had significantly decayed. The old days of nomad power and independence were gone. Apart from China's industrial and technical advantage over the steppe, three main factors combined to reinforce the decline of the Mongol's once-glorious military power and the decay of the nomadic economy. The first was the banner system, which the Qing rulers employed to divide the Mongols and sever their traditional lines of tribal authority; no prince could expand and acquire predominant power, and each of the separate banners was directly responsible to the Qing administration. If a banner prince made trouble, the Qing government had the power to to dismiss him immediately without worrying about his lineage. The second important factor in the taming of the once powerful Mongols was the "Yellow Hat" school of the Tibetan Buddhism. The monasteries and lamas under the authority of the reincarnating lama resident in the capital Beijing were exempt from taxes and services and enjoyed many privileges. The Qing government wanted to tie the Mongols to the empire and it was Qing policy to fuse lamaism with Chinese religious ideas insofar as Mongolian sentiment would allow. For example, the Chinese god of war, the Guandi, was now equated with a figure which had long been identified with the Tibetan and Mongolian folk hero Geser Khan. While the Mongolian population was shrinking, the number of monasteries was growing. In both Inner and Outer Mongolia, about half of the male population became monks, which was even higher than Tibet where only about one third of male population were monks. The third factor in Mongolia's social and economic decline was an outgrowth of the previous factor. The building of monasteries had open Mongolia to the penetration of Chinese trade. Previously Mongolia had little internal trade other than non-market exchanges on a relatively limited scale, and there was no Mongolian merchant class. The monasteries greatly aided the Han Chinese merchants to establish their commercial control throughout Mongolia and provided them with direct access to the steppe. While the Han merchants frequently provoked the anger of the monasteries and the laity for several reasons, the net effect of the monasteries' role was support for Chinese trade. Nevertheless, the empire did make various attempts to restrict the activities of these Han merchants such as the implementation of annual licensing, because it had been the Qing policy to keep the Mongols as a military reservoir, and it was considered that the Han Chinese trade penetration would undermine this objective, although in many cases such attempts had little effects.

The first half of the 19th century saw the heyday of the Qing order. Both Inner and Outer Mongolia continued to supply the Qing armies with cavalry, although the government had tried to keep the Outer Mongols apart from the empire's wars in that century. Since the dynasty placed the Mongols well under its control, the government no longer feared of them. At the same time, as the ruling Manchus had become increasingly sinicized and population pressure in China proper emerged, the dynasty began to abandon its earlier attempts to block Han Chinese trade penetration and settlement in the steppe. After all, Han Chinese economic penetration served the dynasty's interests, because it not only provided support of the government's Mongolian administrative apparatus, but also bound the Mongols more tightly to the rest of empire. The Qing administrators, increasing in league with Han Chinese trading firms, solidly supported Chinese commerce. There was little that ordinary Mongols, who remained in the banners and continued their lives as herdsmen, could do to protect themselves against the growing exactions that banner princes, monasteries, and Han creditors imposed upon them, and ordinary herdsmen had little resource against exorbitant taxation and levies[disambiguation needed

]. In the 19th century, agriculture had been spread in the steppe and pastureland was increasingly converted to agricultural use. Even during the 18th century growing number of Han settlers had already illegally begun to move into the Inner Mongolian steppe and to lease land from monasteries and banner princes, slowing diminishing the grazing areas for the Mongols' livestock. While alienation of pasture in this way was largely illegal, the practice continued unchecked. By 1852, Han Chinese merchants had deeply penetrated Inner Mongolia, and the Mongols had run up unpayable debts. The monasteries had taken over substantial grazing lands, and monasteries, merchants and banner princes had leased many pasture lands to Han Chinese as farmland, although there was also popular resentment against oppressive taxation, Han settlement, shrinkage of pasture, as well as debts and abuse of the banner princes' authority. Many impoverished Mongols also began to take up farming in the steppe, renting farmlands from their banner princes or from Han merchant landlords who had acquired them for agriculture as settlement for debts. Anyway, the Qing attitude towards Han Chinese colonization of Mongolian lands grew more and more favorable under pressure of events, particularly after the Amur Annexation by Russia in 1860. This would reach a peak during the early 20th century, under the name of xinzheng or "New Administration".

]. In the 19th century, agriculture had been spread in the steppe and pastureland was increasingly converted to agricultural use. Even during the 18th century growing number of Han settlers had already illegally begun to move into the Inner Mongolian steppe and to lease land from monasteries and banner princes, slowing diminishing the grazing areas for the Mongols' livestock. While alienation of pasture in this way was largely illegal, the practice continued unchecked. By 1852, Han Chinese merchants had deeply penetrated Inner Mongolia, and the Mongols had run up unpayable debts. The monasteries had taken over substantial grazing lands, and monasteries, merchants and banner princes had leased many pasture lands to Han Chinese as farmland, although there was also popular resentment against oppressive taxation, Han settlement, shrinkage of pasture, as well as debts and abuse of the banner princes' authority. Many impoverished Mongols also began to take up farming in the steppe, renting farmlands from their banner princes or from Han merchant landlords who had acquired them for agriculture as settlement for debts. Anyway, the Qing attitude towards Han Chinese colonization of Mongolian lands grew more and more favorable under pressure of events, particularly after the Amur Annexation by Russia in 1860. This would reach a peak during the early 20th century, under the name of xinzheng or "New Administration".Administrative divisions

Main article: Administrative divisions of Mongolia during QingMongolia was divided into two main parts: Inner (Manchu: Dorgi) Mongolia and Outer (Manchu: Tülergi) Mongolia. The division affected today's separation of modern Mongolia and Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region of China. In addition to the Outer Mongolian 4 aimags and Inner Mongolian 6 leagues, there were also large areas such as the Khobdo frontier and the guard post zone along the Russian border where Qing administration exercised more direct control.

Inner Mongolia[6] Inner Mongolia's original 24 Aimags were torn apart and replaced by 49 khoshuus (banners) which would later be organized into six chuulgans (leagues, assemblys). The eight Chakhar khoshuus and the two Tümed khoshuus around Guihua were directly administered by the Qing government.

- Jirim league

- Josotu league

- Juu Uda league

- Shilingol league

- Ulaan Chab league

- Ihe Juu league

Plus, followings were directly controlled by the Qing emperor.

- Chakhar 8 khoshuu

- Guihua Tümed 2 khoshuu

Outer Mongolia

- Khalkha

- Secen Khan aimag 23 khoshuu

- Tüsheetu Khan aimag 20 khoshuu

- Sain Noyon Khan aimag 24 khoshuu

- Zasagtu Khan aimag 19 khoshuu

- Khövsgöl[7]

- Tannu Uriankhai

- Kobdo Territory 30 khoshuu[citation needed]

- Ili 13 khoshuu (in modern day Xinjiang)[citation needed]

- Khökh Nuur 29 khoshuu (Qinghai)[citation needed]

- Ejine khoshuu (modern day Ejina banner in Alxa aimag, Inner Mongolia)[citation needed]

- Alasha khoshuu (modern day Alxa left and right banners in Alxa aimag, Inner Mongolia)[citation needed]

Culture in Mongolia under Qing rule

Two columns of Tara Mother monastery that was given by the Qing Emperor Qianlong to the Mongols in 1753, Amgalan district, Ulaanbaatar.

Two columns of Tara Mother monastery that was given by the Qing Emperor Qianlong to the Mongols in 1753, Amgalan district, Ulaanbaatar.

While the majority of the Mongolian population during this period is illiterate, the Mongols did produce some excellent literature. For literate Mongols, the 19th century produced much historical writing in both Mongolian and Tibetan and considerable work in philology. This period also saw many translations from Chinese and Tibetan fictions.

Hüree Soyol (Hüree Culture)

During Qing era, Hüree (modern day Ulaanbaatar, capital of Mongolia) was home for rich culture. Hüree style songs constitute a large amount of the Mongolian traditional culture; some examples include "Alia Sender", "Arvan Tavnii Sar", "Tsagaan Sariin Shiniin Negen", "Zadgai Tsagaan Egule" and many more.

Scholarship in Mongolia during Qing period

Many books including chronicles and poems were written by the Mongols during the period of Qing Dynasty. Notable ones include:

-

-

- Altan Tobchi (Golden Chronicle) by Lubsandanzan

- Höh Sudar (The Blue Sutra) by Borjigin Vanchinbaliin Injinashi

-

References

- ^ It was the de facto capital of Outer Mongolia because the Qing Amban located its headquarters in Uliastai to keep eye on the Khalkhas and the Oirats.

- ^ The Cambridge History of China, vol10, pg49

- ^ Paula L. W. Sabloff- Modern mongolia: reclaiming Genghis Khan, p.32

- ^ Marriage and inequality in Chinese society By Rubie Sharon Watson, Patricia Buckley Ebrey, p.177

- ^ Tumen jalafun jecen akū: Manchu studies in honour of Giovanni Stary By Giovanni Stary, Alessandra Pozzi, Juha Antero Janhunen, Michael Weiers

- ^ Michael Weiers (editor) Die Mongolen. Beiträge zu ihrer Geschichte und Kultur, Darmstadt 1986, p. 416ff

- ^ Ch. Banzragch, Khövsgöl aimgiin tüükh, Ulaanbaatar 2001, p. 244 (map)

- Elverskog, Johan. Our Great Qing: The Mongols, Buddhism and the State in Late Imperial China. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2006.

Khorchin · Jalaid · Dörbet (Borjigid) · Gorlos · Kharchin · Tümed · Aohan · Naiman · Bairin (Right and Left Banner) · Jarud · Ongniud · Ar Horqin · Hexigten · Khalkha Left Wing · Üzemchin · Abganar · Khuuchid · Abag · Sonid (Right and Left Banner) · Sizi Tribe · Muminggan · Urad · Khalkha Right Wing · OrdosOuter Mongolia (4 aimags) Tüshiyetu Khan Aimag · Sain Noyan Aimag · Zasagtu Khan Aimag · Secen Khan AimagWestern Hetao Mongolia Alxa Ööled Banner · Ejine Torghuud BannerKhovd region Dörbet (Choros) · Khoton · Myanghad · Zakhchin · Ööld · Altai Uriankhai · Altai Nuur Uriankhai · New Torghuud · New KhoshutOther Mongolian regions Mongols in other provinces Guihua Town Tümed (Shanxi) · Qinghai Mongols (Qinghai) · Old Torghuud (Xinjiang) · Middle Khoshut (Xinjiang) · Damxung Mongols (Tibet) · Barga (Heilongjiang)Categories:- Former countries in Central Asia

- States and territories established in 1635

- States and territories disestablished in 1911

- History of Mongolia

- Mongolia during the Qing Dynasty

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.