- Myles Standish

-

Myles Standish

This portrait, first published in 1885, was alleged to be a 1625 likeness of Standish, although its authenticity has never been proven.[1]Born c. 1584

Possibly Lancashire, EnglandDied October 3, 1656 (aged 72)

Duxbury, MassachusettsAllegiance England

Plymouth ColonyRank Captain Commands held Plymouth Colony militia Battles/wars Eighty Years War (Netherlands)

Wessagusset(Plymouth Colony)Myles Standish (c. 1584 – October 3, 1656; sometimes spelled Miles Standish) was an English military officer hired by the Pilgrims as military advisor for Plymouth Colony. One of the Mayflower passengers, Standish played a leading role in the administration and defense of Plymouth Colony from its inception.[2] On February 17, 1621, the Plymouth Colony militia elected him as its first commander and continued to re-elect him to that position for the remainder of his life.[3] Standish served as an agent of Plymouth Colony in England, as assistant governor, and as treasurer of Plymouth Colony.[4] He was also one of the first settlers and founders of the town of Duxbury, Massachusetts.[5]

A defining characteristic of Standish's military leadership was his proclivity for preemptive action which resulted in at least two attacks (or small skirmishes) on different groups of Native Americans—the Nemasket raid and the Wessagusset massacre. During these actions, Standish exhibited considerable courage and skill as a soldier, but also demonstrated a brutality that angered Native Americans and disturbed more moderate members of the Colony.[6]

One of Standish's last military actions on behalf of Plymouth Colony was the botched Penobscot expedition in 1635. By the 1640s, Standish relinquished his role as an active soldier and settled into a quieter life on his Duxbury farm. Although he was still nominally the commander of military forces in a growing Plymouth Colony, he seems to have preferred to act in an advisory capacity.[7] He died in his home in Duxbury in 1656 at age 72.[8] Although he supported and defended the Pilgrim colony for much of his life, there is no evidence to suggest that Standish ever subscribed to the Pilgrims' religious beliefs or joined their church.[9]

Several towns and military installations have been named for Standish and monuments have been built in his memory. One of the best known depictions of Standish in popular culture was the 1858 book, The Courtship of Miles Standish by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Highly fictionalized, the story presents Standish as a timid romantic.[10] It was extremely popular in the 19th century and played a significant role in cementing the Pilgrim story in American culture.[11]

Contents

Historical background of Plymouth Colony

Main article: Plymouth ColonyStandish was associated for most of his life with a congregation of Protestants known as Separatists. Unlike Puritans, who sought to reform the Church of England, Separatists believed that the Church of England was beyond reform and wished to break from it to form independent congregations.[12] One group of Separatists formed in Scrooby, Nottinghamshire, led by ministers Richard Clyfton and John Robinson, and by a lay minister or "elder" William Brewster. English authorities outlawed and persecuted such congregations. In 1608, the Scrooby congregation relocated to Holland in the Dutch Republic, where freedom of religion was permitted.[13] The group eventually settled in Leiden, Holland, where it remained for 12 years.

Although they enjoyed religious freedom in Holland, the members of the Scrooby congregation were troubled by the foreign culture of Leiden and they wished to raise their children in a strictly English environment. In 1620, with the permission of King James I of England and backing from a group of financial investors in London known as the Merchant Adventurers, the Scrooby congregation departed for the New World aboard the Mayflower to establish a colony in North America.[14]

Not all the Mayflower passengers were Separatists. The Merchant Adventurers recruited a number of colonists seeking financial opportunity in the New World.[14] Others, such as Myles Standish, had been hired by the Separatists specifically for their expertise in certain areas. Thus, Standish traveled aboard the Mayflower for military professional, not for religious reasons. Standish's religious leanings have been the source of some debate. Whatever his denomination, he sympathized with the Separatists, supporting and defending Plymouth Colony for much of his life, although there is no evidence as to whether he joined their church.[15]

In what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts, the passengers of the Mayflower established a colony referred to at the time as "New Plymouth" (although the name and spelling varied). The term "Pilgrims" is now used primarily to refer to the Separatist congregation, although it is often applied to all the original settlers of Plymouth Colony (both Separatist and Anglican).

Birthplace and early military service

Little is definitively known of Myles Standish's origins and early life. His place of birth has been subject to debate among historians for more than 150 years.[15] At the center of the debate is language in Myles Standish's will, drafted in Plymouth Colony in 1656, regarding his rights of inheritance. Standish wrote:

I give unto my son & heire apparent Alexander Standish all my lands as heire apparent by lawfull decent in Ormskirke Borscouge Wrightington Maudsley Newburrow Crowston and in the Isle of man and given to mee as Right heire by lawfull decent but Surruptuously detained from mee My great Grandfather being a 2cond or younger brother from the house of Standish of Standish.[15]

The places named by Standish, with the exception of the Isle of Man, are all in Lancashire, England, leading some to conclude that Standish was born in Lancashire—possibly in the vicinity of Chorley where a branch of the Standish family owned a manor known as Duxbury Hall.[16] However, efforts to link Standish to the Standishes of Duxbury Hall have proven inconclusive. A competing theory focuses on Standish's mention of the Isle of Man and argues that Myles belonged to a Manx branch of the Standish family. No definitive documentation exists in either location to provide clear evidence of Standish's birthplace.[15]

Possibly the best source, however brief, on Standish's origins and early life is a short passage recorded by Nathaniel Morton, secretary of Plymouth Colony, who wrote in his New England's Memorial, published in 1669, that Standish:

...was a gentleman, born in Lancashire, and was heir apparent unto a great estate of lands and livings, surreptitiously detained from him; his great grandfather being a second or younger brother from the house of Standish. In his younger time he went over into the low countries [sic], and was a soldier there, and came acquainted with the church at Leyden, and came over into New England, with such of them as at the first set out for the planting of the plantation of New Plimouth, and bare a deep share of their first difficulties, and was always very faithful to their interest.[17]

Sir Horatio Vere was the commander of English troops in Holland during the Siege of Ostend, under whom Standish likely served.

Sir Horatio Vere was the commander of English troops in Holland during the Siege of Ostend, under whom Standish likely served.

The circumstances of Standish's early military career in Holland (the "low countries" to which Morton alluded) are vague at best. At the time, the Dutch Republic was embroiled in the Eighty Years War with Spain. Queen Elizabeth I of England chose to support the Protestant Dutch Republic and sent troops to fight the Spanish in Holland. Some historians, such as Nathaniel Philbrick, refer to Standish as a "mercenary," suggesting that he was a hired soldier of fortune seeking opportunity in Holland.[14] Others, such as historian Justin Winsor, claim that Standish received a lieutenant's commission in the English army and was subsequently promoted to captain in Holland.[16] Jeremy Bangs, a leading scholar of Pilgrim history, noted that Standish likely served under Sir Horatio Vere, an English general who had recruited soldiers in both Lancashire and the Isle of Man, among other places, and who led the English troops in Holland at the time Standish was there.[15]

Whether commissioned officer, mercenary, or both, Standish apparently came to Holland around 1603 and may, according to historian Tudor Jenks, have seen service during the Siege of Ostend in which Vere's English troops were involved.[18] The subsequent Twelve Years' Truce (1609–1621) between Spain and the Dutch Republic would have ended Standish's service, although scholars are uncertain if Standish was still in active service.

Standish first appears in the written record in 1620 when, living in Leiden, Holland, he was hired by the Pilgrims to act as their advisor on military matters.[19] At that time he already was using the title of "Captain." When considering candidates for this important position, the Pilgrims had at first hoped to engage Captain John Smith. As one of the founders of the English colony at Jamestown, Virginia, Smith had explored and mapped the North American coast. When the Pilgrims approached him to return to the New World, Smith expressed interest. His experience made him an attractive candidate, but the Pilgrims ultimately decided against Smith: His price was too high and the Pilgrims feared his fame and bold character might lead him to become a dictator.[20]

Standish, having lived in Leiden with his wife Rose, was apparently already known to the Pilgrims.[15] In the summer of 1620, Myles and Rose Standish embarked with the Pilgrims for the New World.[21]

Establishment of Plymouth Colony

The Mayflower first made landfall at the tip of Cape Cod, now the site of Provincetown, Massachusetts.[22] The Pilgrims had originally intended, and been given permission by the Crown, to settle at the Hudson River, now the site of New York City. When it became apparent that, due to a shortage of provisions, they would have to settle on or near Cape Cod, the leaders of the colony decided to draw up the Mayflower Compact to ensure a degree of law and order in this place where they had no legal rights to settle. Myles Standish was the fourth to sign the compact.[23]

While the Mayflower was anchored off Cape Cod, Standish urged the colony's leaders to allow him to take a party ashore to find a suitable place for settlement.[24] On November 15, 1620, he led 16 men in a foot exploration of the northern portion of Cape Cod.[25] On December 11, a group of 18 settlers, including Standish, made an extended exploration of the shore of Cape Cod by boat.[26] Spending their nights ashore surrounded by make-shift barricades of tree branches, the settlers were attacked one night by a group of about 30 Native Americans. At first the Englishmen panicked, but Standish calmed them, urging the settlers not to fire their matchlock muskets unnecessarily.[27] The incident, known as the First Encounter, took place in present-day Eastham, Massachusetts.

After further exploration, in late December 1620 the Pilgrims chose a location in present-day Plymouth Bay as the site for their settlement. Standish provided important counsel on the placement of a small fort in which cannon were mounted, and on the layout of the first houses for maximum defensibility.[2] Only one house (consisting of a single room) had been built when illness struck the settlers. Of the roughly 100 who first arrived, only 50 survived the first winter.[28] Standish's wife, Rose, died in January.

Standish himself was one of the very few who did not fall ill and William Bradford (soon to be governor of Plymouth Colony) credited Standish with comforting many and being a source of strength to those who suffered.[29] Standish tended to Bradford during his illness and this was the beginning of a decades-long friendship.[23] Bradford held the position of governor for most of his life and, by necessity, worked closely with Standish. In terms of character, the two men were opposites—Bradford was patient and slow to judgment while Standish was well-known for his fiery temper.[30] Despite their differences, the two worked well together in managing the colony and responding to dangers as they arose.[31]

Defense of Plymouth Colony

By February 1621, the colonists had sighted Native Americans several times, but there had been no communication. Anxious to prepare themselves in the event of hostilities, on February 17, 1621, the men of the colony met to form a militia consisting of all able-bodied men and elected Standish their commander. Although the leaders of Plymouth Colony had already hired him for that role, this vote ratified the decision by democratic process.[3] The men of Plymouth Colony continued to re-elect Standish to that position for the remainder of his life. As captain of the militia, Standish regularly drilled his men in the use of pikes and muskets.[32]

Contact with the Native Americans came in March 1621 through Samoset, an English-speaking Abenaki who arranged for the Pilgrims to meet with Massasoit, the sachem of the nearby Pokanoket tribe. On March 22, the first governor of Plymouth Colony, John Carver, signed a treaty with Massasoit, declaring an alliance between the Pokanoket and the Englishmen and requiring the two parties to defend each other in times of need.[33] Governor Carver died the same year and the responsibility of upholding the treaty fell to his successor, William Bradford. As depicted by historian Nathaniel Philbrick, Bradford and Standish were frequently preoccupied with the complex task of reacting to threats against both the Pilgrims and the Pokanokets from tribes such as the Massachusett and the Narragansett.[31] As threats arose, Standish typically advocated intimidation to deter their rivals. Although such behavior at times made Bradford uncomfortable, he found it an expedient means of maintaining the treaty with the Pokanoket.[34]

Nemasket raid

The first challenge to the treaty came in August 1621 when a sachem named Corbitant began to undermine Massasoit's leadership. In the Pokanoket village of Nemasket, now the site of Middleborough, Massachusetts, about 14 miles (23 km) west of Plymouth, Corbitant worked to turn the people of Nemasket against Massasoit.[31] Bradford sent two trusted interpreters, Tisquantum (known to the English as Squanto) and Hobbamock, to determine what was happening in Nemasket. Tisquantum had been pivotal in providing counsel and aid to the Pilgrims, ensuring the survival of the colony. Hobbamock, another influential ally, was a pniese—a high-ranking advisor to Massasoit—and a warrior who commanded particular respect and fear among Native Americans. When Tisquantum and Hobbamock arrived in Nemasket, Corbitant took Tisquantum captive and threatened to kill him. Hobbamock escaped to warn Plymouth.[35]

Bradford and Standish agreed that this represented a dangerous threat to the English-Pokanoket alliance and decided to act quickly. On August 14, 1621, Standish led a group of 10 men to Nemasket, determined to kill Corbitant.[31] They were guided by Hobbamock who quickly befriended Standish. The two men would be close for the remainder of their lives. In his old age, Hobbamock became part of Standish's household in Duxbury.[36]

Reaching Nemasket, Standish planned a night attack on the wigwam in which Corbitant was believed to be sleeping. That night, Standish and Hobbamock burst into the shelter, shouting for Corbitant. As frightened Pokanokets attempted to escape, Englishmen outside the wigwam fired their muskets, wounding a Pokanoket man and woman who were later taken to Plymouth to be treated. Standish soon learned that Corbitant had already fled the village and Tisquantum was unharmed.[37]

Although Standish had failed to capture Corbitant, the raid had the desired effect. On September 13, 1621, nine sachems, including Corbitant, came to Plymouth to sign a treaty of loyalty to King James.[38]

Palisade

Plimoth Plantation, a reconstruction of the original Pilgrim village in Plymouth, Massachusetts, includes a replica of the palisade surrounding the settlement

In November 1621, a Narragansett messenger arrived in Plymouth and delivered a bundle of arrows wrapped in a snakeskin. The Pilgrims were told by Tisquantum and Hobbamock that this was a threat and an insult from the Narragansett sachem, Canonicus.[39] The Narragansett, who lived west of what is now known as Narragansett Bay in present day Rhode Island, were one of the more powerful tribes in the region. Bradford sent back the snakeskin filled with gunpowder and shot in an effort to show they were not intimidated.

Taking the threat seriously, Standish urged that the colonists encircle their small village with a palisade made of tall, upright logs. The proposal would require a wall more than half a mile (or 0.8 km) long.[40] In addition, Standish recommended the construction of strong gates and platforms for shooting over the wall. Although the colony had recently been reinforced by the arrival of new colonists from the ship Fortune, there were still only 50 men to work on the task. Despite the challenges, the settlers constructed the palisade per Standish's recommendations in just three months, finishing in March 1622. Standish divided the militia into four companies, one to man each wall, and drilled them in defending the village in the event of attack.[41]

Wessagusset

A more serious threat came from the Massachusett tribe to the north and was precipitated by the arrival of a new group of English colonists. In April 1622, the vanguard of a new colony arrived in Plymouth. They had been sent by merchant Thomas Weston to establish a new settlement somewhere near Plymouth. The men chose a site on the shore of what is now the Fore River in present-day Weymouth, Massachusetts, about 25 miles (40 km) north of Plymouth. They called their colony Wessagusset. The settlers of the poorly managed colony infuriated the Massachusett tribe, through theft and recklessness.[42] By March 1623, Massasoit had learned that a group of influential Massachusett warriors intended to destroy both the Wessagusset and the Plymouth colonies. Massasoit warned the Pilgrims to strike first. One of the colonists of Wessagusset, Phineas Pratt, verified that his settlement was in danger. Pratt managed to escape to Plymouth and reported that the English in Wessagusset had been repeatedly threatened by the Massachusett, the settlement was in a state of constant watchfulness, and that men were dying at their posts from starvation.[43]

Bradford called a public meeting at which the Pilgrims decided to send Standish and a small group of eight, including Hobbamock, to Wessagusset to kill the leaders of the alleged plot to wipe out the English settlements.[44] The mission had a personal aspect for Standish. One of the warriors threatening Wessagusset was Wituwamat, a Neponset who had earlier insulted and threatened Standish.[45]

Arriving at Wessagusset, Standish found that many of the Englishmen had gone to live with the Massachusett. Standish ordered them called back to Wessagusset. The day after Standish's arrival, Pecksuot, a Massachusett warrior and leader of the group threatening Wessagusset, came to the settlement with Wituwamat and other warriors. Although Standish claimed simply to be in Wessagusset on a trading mission, Pecksuot said to Hobbamock, "Let him begin when he dare...he shall not take us unawares."[46] Later in the day, Pecksuot approached Standish and, looking down on him, said, "You are a great captain, yet you are but a little man. Though I be no sachem, yet I am of great strength and courage."[47]

The next day, Standish arranged to meet with Pecksuot over a meal in one of Wessagusset's one-room houses. Pecksuot brought with him Wituwamat, a third warrior, an adolescent boy (Wituwamat's brother) and several women. Standish had three men of Plymouth and Hobbamock with him in the house. On an arranged signal, the English shut the door of the house and Standish attacked Pecksuot, stabbing him repeatedly with the man's own knife.[47] Wituwamat and the third warrior were also killed. Leaving the house, Standish ordered two more Massachusett warriors put to death. Gathering his men, Standish went outside the walls of Wessagusset in search of Obtakiest, a sachem of the Massachusett tribe. The Englishmen soon encountered Obtakiest with a group of warriors and a skirmish ensued during which Obtakiest escaped.[48]

Having accomplished his mission, Standish returned to Plymouth with Wituwamat's head.[49] The leaders of the alleged plot to destroy the English settlements had been killed and the threat removed, but the action had unexpected consequences. The settlement of Wessagusset, which Standish had, in theory, been trying to protect, was all but abandoned after the incident. Most of the settlers departed for an English fishing post on Monhegan Island. The attack also caused widespread panic among Native Americans throughout the region. Villages were abandoned and, for some time, the Pilgrims had difficulty reviving trade.[50]

Pastor John Robinson, who was still in Leiden, criticized Standish for his brutality.[51] Bradford, too, was uncomfortable with Standish's methods, but defended him in a letter, writing, "As for Capten Standish, we leave him to answer for him selfe, but this we must say, he is as helpfull an instrument as any we have, and as careful of the general good."[52]

Dispersal of Merrymount settlers

In 1625, another group of English settlers established an outpost not far from the site of Wessagusset. Located in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts, about 27 miles (43 km) north of Plymouth, the settlement was officially known as Mount Wollaston, but soon earned the nickname "Merrymount." Thomas Morton, leader of the small group of Englishmen, encouraged behavior that the Pilgrims found objectionable and dangerous. The men of Merrymount built a maypole, drank liberally, refused to observe the Sabbath and sold weapons to Native Americans.[53] Bradford found the latter particularly disturbing and, in 1628, ordered Standish to lead an expedition to arrest Morton.[54]

Standish arrived with a group of men to find that the small band at Merrymount had barricaded themselves within a small building. Morton eventually decided to attack the men from Plymouth but, allegedly, the Merrymount group was too drunk to handle their weapons.[54] Morton aimed a weapon at Standish, which the captain purportedly ripped from Morton's hands. Standish and his men took Morton to Plymouth and eventually sent him back to England. Later, Morton wrote a book, New English Canaan, in which he referred to Myles Standish as, "Captain Shrimp," and wrote, "I have found the Massachusetts Indians more full of humanity than the Christians."[55]

Penobscot expedition

Having defended Plymouth from Native Americans and other Englishmen, Standish's last significant expedition was against the French.[56] On the Penobscot River, in what is now Castine, Maine, the French established a trading post in 1613. English forces captured the settlement in 1628 and turned it over to Plymouth Colony. It was a valuable source of furs and timber for the Pilgrims for seven years. However, in 1635, the French mounted a small expedition and easily reclaimed the settlement.[57] Determined that the post be reclaimed in Plymouth Colony's name, William Bradford ordered Captain Standish to take action. This was a significantly larger proposition than the small expeditions Standish had previously led. To accomplish the task, Standish chartered a ship, the Good Hope, captained by a man named Girling.[57] Standish's plan appears to have been to bring the Good Hope within cannon range of the trading post and to bombard the French into surrender. Unfortunately, Girling ordered the bombardment before the ship was within range and quickly spent all the powder on board. Standish gave up the effort.[57]

By this time, the neighboring and more populous Massachusetts Bay Colony had been established. Bradford appealed to leaders of the colony in Boston for help in reclaiming the trading post. The Bay Colony refused. The incident was indicative of the rivalry which persisted between Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies.[57] In 1691, the two colonies merged to become the royal Province of Massachusetts Bay.

Settlement in Duxbury

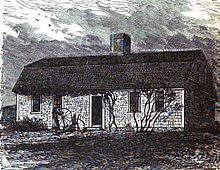

The Alexander Standish House built by Myles Standish's son on the Captain's farm in Duxbury, Massachusetts

In 1625, Plymouth Colony leaders appointed Standish to travel to London to negotiate new terms with the Merchant Adventurers. If a settlement could be reached and the Pilgrims could pay off their debt to the Adventurers, then the colonists would have new rights to allot land and settle where they pleased. Standish was not successful in his negotiations and returned to Plymouth in April 1626.[58] Another effort later in 1626, this time negotiated by Isaac Allerton, was successful, and several leading men of Plymouth, including Standish, paid off the colony's debt to the Adventurers.[59]

Now free of the directives of the Merchant Adventurers, the leaders of Plymouth Colony exerted their new-found autonomy by organizing a land division in 1627. Large farm lots were parceled out to each family in the colony along the shore of the present-day towns of Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury and Marshfield, Massachusetts. Standish received a farm of 120 acres (49 ha) in what would become Duxbury.[60] Standish built a house and settled there around 1628.[61]

At this point, Standish had a growing family. In 1623, he had married his second wife, Barbara, who arrived in Plymouth earlier that year aboard the ship Anne. Very little is known of her origins (her maiden name has not been definitively proven), although a persistent theory, repeated by several historians including Tudor Jenks and Annie Haxtun, suggests that Barbara was a sister of Standish's first wife Rose and that Standish specifically sent for her.[62] They eventually had seven children: Alexander, Charles, John, Josiah, Myles, Lora, and another Charles.[63]

Standish grave site in the Myles Standish Cemetery in Duxbury

There are indications that, by 1635 (after the Penobscot expedition), Standish began to seek a quieter life, maintaining the livestock and fields of his Duxbury farm.[63] About 51 years old at that time, Standish began to relinquish the responsibility of defending the colony to a younger generation. A note in the colony records of 1635 indicates that Lieutenant William Holmes, Standish's immediate subordinate, was appointed to train the militia.[64] When the Pequot War loomed in 1637, Standish was appointed to a committee to raise a company of 30 men, but it was Holmes who led the company in the field.[64]

The families living in what had come to be referred to as Duxbury (sometimes "Duxborough") requested to be set off from Plymouth as a separate town with their own church and minister. This request was granted in 1637. Some, including historian Justin Winsor, have insisted that the name of the town of Duxbury was given by Standish in honor of Duxbury Hall, near Chorley in Lancashire, which was owned by a branch of the Standish family.[65] Although the coincidence would suggest that Standish had something to do with the naming of Duxbury, Massachusetts, no records exist to indicate how the town was named.[66]

During the 1640s, Standish took on an increasingly administrative role. He served as a surveyor of highways, as Treasurer of the Colony from 1644 to 1649, and on various committees to lay out boundaries of new towns and inspect waterways.[67] In 1642, his old friend Hobbamock, who had been part of his household, died and was buried on Standish's farm in Duxbury.[36]

Standish died on October 3, 1656, of "strangullion" or strangury, a condition often associated with kidney stones or bladder cancer.[16] He was buried in Duxbury's Old Burying Ground, now known as the Myles Standish Cemetery.[68]

Legacy

Standish's true-life role in defending Plymouth Colony (and the sometimes brutal tactics he employed) were largely obscured by the fictionalized character created by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his book The Courtship of Miles Standish. Historian Tudor Jenks wrote that Longfellow's book had "no claim to be considered other than a pleasant little fairystory, and as an entirely misleading sketch of men and matters in old Plymouth."[69] However, the book elevated Standish to the level of folk hero in Victorian America. In late 19th century Duxbury, the book generated a movement to build monuments in Standish's honor, a beneficial by-product of which would be increased tourism to the town.[11]

The first of these monuments was the largest.[11] The cornerstone was laid for the Myles Standish Monument in Duxbury in 1872 with a crowd of ten thousand people attending the ceremonies.[11] Finished in 1898, it was the third tallest monument to an individual in the United States, surpassed only by the first dedicated Washington Monument (178 feet) in Baltimore, Maryland finished in 1829 and the Washington Monument (555 feet) in Washington, D.C. dedicated in 1885.[11] At the top of the monument, which is 116 feet (35 m) overall, stands a 14-foot (4.3 m) statue of Standish.[11]

A second, smaller monument was placed over the alleged site of Myles Standish's grave in 1893.[68] Two exhumations of Standish's remains were undertaken in 1889 and 1891 to determine the location of the Captain's resting place. A third exhumation took place in 1930 to place Standish's remains in a hermetically sealed chamber beneath the grave-site monument.[68]

The site of Myles Standish's house, revealing only a slight depression in the ground where the cellar hole was, is now a small park owned and maintained by the town of Duxbury.[70]

Standish, Maine, is named for the Captain, as well as the neighborhood of Standish, Minneapolis. At least two forts were named after Standish—an earthen fort on Plymouth's Saquish Neck built during the American Civil War and a larger cement fort built on Lovells Island in Boston Harbor in 1895. Both forts are now abandoned.[71]

See also

Notes

- ^ Winsor, History of Boston, 65.

- ^ a b Philbrick, 84.

- ^ a b Philbrick, 88.

- ^ Winsor, The History of the Town of Duxbury, 49.

- ^ Wentworth, 3.

- ^ Philbrick, 153–156.

- ^ Jenks, 242.

- ^ Winsor, History of the Town of Duxbury, 95.

- ^ Goodwin, 70.

- ^ Jenks, 182.

- ^ a b c d e f Browne and Forgit, 66.

- ^ Stratton, 17.

- ^ Stratton, 18.

- ^ a b c Philbrick, 25.

- ^ a b c d e f Bangs, Myles Standish, Born Where?

- ^ a b c Winsor, History of the Town of Duxbury, 97.

- ^ Stratton, 357.

- ^ Jenks, 38.

- ^ Stratton, 19.

- ^ Philbrick, 59.

- ^ Stratton, 406.

- ^ Stratton, 20.

- ^ a b Haxtun, 17

- ^ Philbrick, 61.

- ^ Schmidt, 69.

- ^ Stratton, 75.

- ^ Philbrick, 71.

- ^ Schmidt, 88.

- ^ Schmidt, 86.

- ^ Jenks170

- ^ a b c d Philbrick, 114.

- ^ Philbrick, 89.

- ^ Philbrick, 99.

- ^ Philbrick, 162.

- ^ Schmidt, 105.

- ^ a b Winsor, History of the Town of Duxbury, 33.

- ^ Philbrick, 115.

- ^ Jenks, 124.

- ^ Schmidt, 114.

- ^ Philbrick, 127.

- ^ Philbrick, 129.

- ^ Jenks, 165.

- ^ Philbrick, 147.

- ^ Jenks, 174.

- ^ Philbrick, 149.

- ^ Jenks, 175.

- ^ a b Philbrick, 151.

- ^ Philbrick, 152.

- ^ Jenks, 178.

- ^ Philbrick, 154.

- ^ Jenks, 179.

- ^ Stratton, 358.

- ^ Philbrick, 163.

- ^ a b Schmidt, 161.

- ^ Philbrick, 164.

- ^ Goodwin, 224–225

- ^ a b c d Jenks, 224.

- ^ Porteus, 6.

- ^ Pillsbury, 23.

- ^ Wentworth, 12.

- ^ Winsor, History of Duxbury, 10.

- ^ Jenks, 181.

- ^ a b Wentworth, 29.

- ^ a b Winsor, History of the Town of Duxbury, 89.

- ^ Winsor, History of the Town of Duxbury, 11.

- ^ Leach, 46.

- ^ Winsor, History of the Town of Duxbury, 44.

- ^ a b c Browne and Forgit, 40–41.

- ^ Jenks, 239.

- ^ Pillsbury, 25.

- ^ Butler, 81–82.

References

- Bangs, Jeremy D. (2006). "Myles Standish, Born Where? The State of the Question". SAIL 1620. Society of Mayflower Descendants in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. http://www.sail1620.org/history/35-biographies/51-myles-standish.html. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- Browne, Patrick T.J.; Forgit, Norman (2009). Duxbury...Past & Present. Duxbury, Massachusetts: The Duxbury Rural and Historical Society, Inc.. ISBN 0941859118.

- Butler, Gerald (2000). The Military History of Boston's Harbor Islands. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0738504645. http://books.google.com/books?id=h0nwwK0inAQC&pg=PA65&dq=%22Fort+Standish%22&cd=13#v=onepage&q=&f=false0.

- Goodwin, John A. (1920) [1879]. The Pilgrim Republic: An Historical Review of the Colony of New Plymouth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. OCLC 316126717. http://books.google.com/books?id=1h86ThQYxgEC&printsec=frontcover&dq=the+pilgrim+republic&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Haxtun, Annie A. (1899). Signers of the Mayflower Compact. Baltimore: The Mail and Express. OCLC 2812063.

- Jenks, Tudor (1905). Captain Myles Standish. New York: The Century Co. OCLC 3000476. http://books.google.com/books?id=rMVLAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Myles+Standish&cd=8#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Leach, Frances (1987). "Notes on the Name Duxbury". The Duxbury Book, 1637–1987. Duxbury, Massachusetts: Duxbury Rural and Historical Society, Inc.. ISBN 0941859002.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2006). Mayflower: A Story of Community, Courage and War. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143111979. http://books.google.com/books?id=qk9AXww_XysC&printsec=frontcover&dq=mayflower&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Pillsbury, Katherine H. (1999). Duxbury: A Guide. Duxbury, Massachusetts: The Duxbury Rural and Historical Society, Inc.. ISBN 0941859045.

- Porteus, Thomas C. (1920). Captain Myles Standish: His Lost Lands and Lancashire Connections. Manchester: The University of Manchester Press. OCLC 2134828. http://books.google.com/books?id=msRLAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Captain+Myles+Standish&cd=2#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Schmidt, Gary D. (1999). William Bradford: Plymouth's Faithful Pilgrim. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.. ISBN 082851517. http://books.google.com/books?id=BijffNh7pLAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=William+Bradford&cd=5#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Stratton, Eugene A. (1986). Plymouth Colony: Its History & People, 1620–1691. Salt Lake City: Ancestry Incorporated. ISBN 0916489132. http://books.google.com/books?id=17zCU76ZtH0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22Plymouth+colony%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Wentworth, Dorothy (2000) [1973]. Settlement and Growth of Duxbury 1628–1870. Duxbury, Massachusetts: Duxbury Rural and Historical Society. ISBN 0941859053.

- Winsor, Justin (1849). History of the Town of Duxbury. Boston: Crosby & Nichols. OCLC 32063251. http://books.google.com/books?id=3koWAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=History+of+Duxbury&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Winsor, Justin (1885). The Memorial History of Boston vol. 1. Boston: James R. Osgood & Co. OCLC 978152. http://books.google.com/books?id=M6wTAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA65&dq=Myles+Standish+portrait&cd=12#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

External links

- Myles Standish from MayflowerHistory.com

"Standish, Myles". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Standish, Myles". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

Categories:- 1580s births

- 1656 deaths

- 16th-century English people

- 17th-century English people

- Mayflower passengers

- Plymouth, Massachusetts

- American folklore

- People from Duxbury, Massachusetts

- 17th-century American people

- People of the Tudor period

- People of the Stuart period

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.