- Comic book death

-

This article is about the deaths of characters in comic books. For the personification of death in comic books, see Death (comics).

In the comic book fan community, the apparent death and subsequent return of a long-running character is often called a comic book death. While death is a serious subject, a comic book death is generally not taken seriously and is rarely permanent or meaningful. Commenting on the impact and role of comic book character deaths in the modern comics, writer Geoff Johns said:[1]

“ Death in superhero comics is cyclical in its nature, and that's for a lot of reasons, whether they are story reasons, copyright reasons, or fan reasons. But death doesn't exist the same way it does in our world, and thank God for that. I wish death existed in our world as it does in comics. ” The phenomenon of comic book death is particularly common for superhero characters. Writer Danny Fingeroth suggests that the nature of superheroes requires that they be both ageless and immortal.[2]

A common expression regarding comic book death was once "The only people who stay dead in comics, are Bucky, Jason Todd, and Uncle Ben."[3] referring to the seminal importance of those character's deaths to Captain America, Batman, and Spider-Man respectively. However, after the former two were brought back in 2005, the phrase was changed to only recognize Uncle Ben.

Some comic book writers have killed off characters to gather publicity or to create dramatic tension. In other instances, a writer kills off a character for which he/she did not particularly care for, but upon their leaving the title, another writer who liked this character brings them back. More often, however, the publishing house intends to permanently kill off a long-running character, but fan pressure or creative decisions push the company to resurrect the character. Still other characters remain permanently dead, but are replaced by characters who assume their personas (such as Wally West taking over for Barry Allen as The Flash), so the death does not cause a genuine break in character continuity. At other times, a character dies and stays dead simply because his or her story is over.

The term "comic book death" is usually not applied to characters such as DC's Solomon Grundy, Resurrection Man and Marvel's Mr. Immortal, who have the ability to come back to life as an established character trait or power; rather it is usually applied when one would normally expect death to be permanent but the character is later resurrected through a plot device not previously established.

Contents

Notable examples

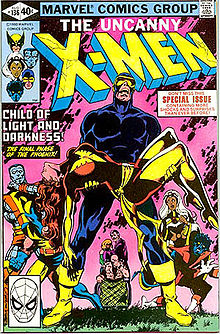

At least three comic book deaths are well known. The first two are the 1980 "death" of Jean Grey in Marvel's Dark Phoenix Saga and that of Superman in DC's highly-publicized 1993 Death of Superman storyline. There is one major distinction between the two, however - whereas it was never intended that Superman's death be permanent, and that he would return to life at the conclusion of the story,[4] Jean's passing (one of many temporary deaths among the X-Men) was written as the true and permanent death of the character,[citation needed] only to be retconned a few years later to facilitate her return. In more recent history, the death of Captain America made real-world headlines in early 2007[5] when he met his apparent end, but Steve Rogers returned in Captain America: Reborn in late 2009.

In DC Comics' Batman: RIP storyline, Batman was apparently killed. It was revealed that he had survived, only for him to disappear into the timestream in the Final Crisis storyline. Dick Grayson took on the mantle of Batman, and Batman came back to the present in the "Return of Bruce Wayne" storyline, published about a year and a half after "Final Crisis".

Because death in comics is so often temporary, readers rarely take the death of a character seriously - when someone dies, the reader feels very little sense of loss, and simply left wondering how long it will be before they return to life. This, in turn, has led to a common piece of comic shop wisdom: "No one stays dead except Bucky,Jason Todd and Uncle Ben"[6] referring to Captain America's sidekick (retconned dead since 1964), Batman's second Robin (dead since 1988), and Peter Parker's uncle (dead since 1962), respectively. This long-held tenet was finally broken in 2005, when Jason Todd returned to life and Bucky Barnes was reported to have survived the accident that seemingly killed him, remaining in the shadows for decades.

Comic book characters themselves have often made comments about the frequency of resurrections, notably Charles Xavier who commented "in mutant heaven there are no pearly gates, but instead revolving doors."[7]

Parodies

Comic book deaths have been parodied by Peter Milligan in X-Statix, in which all the characters had died by the end of the series. In X-Statix Presents Dead Girl, it is further parodied. A group of dead villains want to return to life claiming "it happens all the time". Dr. Strange says that a character will be "promoted" to life if enough people want her alive.

In the 2000 X-Men film, after a defeated Storm re-enters the fight, Toad complains, "Don't you people ever die?"

In Joss Whedon's Astonishing X-Men #6, Emma Frost states that "Jean Grey is dead" only to have Agent Brand respond with a sarcastic "Yeah, that'll last". Similarly, in the Endangered Species series, Dark Beast says on being told that Jean and Nate Grey are dead, "Well, yes, but with that family, I've found it's best to get frequent updates. Exactly how dead, at this moment in time?"

In Next Wave: Agents of Hate, two of the characters are talking about the X-Men member Magik. One of them comments that she is dead and the other replies "So what? The X-Men come back to life more than Jesus".

Comic book death has been also parodied by Mr. Immortal of the Great Lakes Avengers, a mutant whose power is to resurrect from the dead. Consequently, he is killed and revived in almost all appearances. The concept was further parodied by Dan Slott's 2005 GLA miniseries, in which one member dies in every issue.

The Simpsons also parodied comic book deaths in the episode "Radioactive Man" in which Milhouse mentions an issue of Radioactive Man in which the eponymous character and his sidekick Fallout Boy die on every page. The killing of Kenny in practically every episode of South Park is a parody of the form, treated as being so pervasive that for much of the series it is not even worth providing a contrived explanation. (It is eventually revealed in Season 14 that Kenny has a "super power" of immortality, but the super power includes everyone forgetting his many, many deaths.)

The Comic Carnival Hotline had a recurring character in "Methuselah Spitshank, World's Oldest Comic Collector," who would die in every episode. Usual host Ramone would say "Don't worry folks, the writers will bring him back when they need him." In one episode, Mr. Spitshank survived the entire episode only to die when Ramone announces that the next episode is "when Dweebie, his boy assistant, runs out of paper towels, and uses a mint condition copy of Detective Comics #27 to dry his hands."

Outside comic books

The return of a character previously thought dead is certainly not limited to comic books. An early and famous example is the return of Sherlock Holmes after his death at the Reichenbach Falls. In many slasher films and monster movies, the killer or monster seemingly dies at the end of the film only to return for a sequel. Daytime and prime-time soap operas are notorious for comic book deaths; famously, an entire season of Dallas was retconned into one character's dream[8] so that a character who had been dead throughout that season could return. Even before Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan opened in June 1982, the media reported that Spock, who died at the end of the film, would return in the sequel.[9] In the Manga/Anime Dragon Ball the main character Son Goku is killed off without the possibility of being revived by the Dragon Balls, only to have a Kaioshin give his life to him seven years later.

Common retcons

A common way to reformulate the death of a character is to create a retcon stating that the death scene did take place as seen, but something else took place as well, preventing the character from actually dying. Usually it is a severe near-death injury or situation (for example, an explosion), from which the character is saved (off-panel, detailed in the subsequent retcon) by his powers[N 1] or skills, by good luck, or by the help of someone else. The death scene may also be a character's deliberate plot that simulates his own death or that of someone else for a certain purpose. In these cases, the death scene may have been staged, or it may have been an illusion of some kind. In other cases, the events took place as originally depicted, but instead of dying the character may be revealed to have been in a coma. This premise is often misused for injuries and illnesses that do not involve head trauma, the primary trigger for coma. Additionally, coma is often misrepresented as allowing a character to instantly resume their lives without the lengthy recovery time needed in reality (although the powers of the individual in question may help their recovery). Variations on this theme include suspended animation and cryogenic suspension, both of which are also used with varying degrees of scientific implausibility, and other types of metamorphosis created for the fictional universe. In more extreme examples, the consciousness of the character may be transferred to another body, human or otherwise.

Another way, in line with the mentioned one, is when a character dies but it is later revealed that it wasn't the real character who died, but someone else posing as him, such as a clone, impostor or shape-shifter.[N 2] However, once comic book death became a standard, the trick was also used in another way: a character dies and returns, but the impostor ends up becoming the returned character, meaning that the original one remained dead all the time.[N 3]

Other characters experience real deaths, but some cosmic or magical being makes them resurrect, either intentionally or unintentionally. Those kinds of resurrection may be intended to be either permanent or last only for a single story involving such a being. In those last cases the character may be resurrected as a zombie (for example: the Blackest Night arc in DC Comics, or the Necrosha arc in Marvel Comics) or harmed in some other way. Such beings may also have access to some afterlife where the soul of the character fled after dying (such as fictional variations of Heaven or Hell), and have some limited interaction with the character even while keeping him dead. Time travel,[N 4] reality manipulation or other narrative tricks may also be used to undo big changes in the fictional universe (such as the death of characters) by setting them out of continuity and restoring things to a previous point.

A less controversial solution is to make a dead character remain dead, and have a similar one assume his super-hero or super-villain identity and replace him as a successor. Sometimes this even leads to the creation of complete successive timelines of people assuming the role, such as Wally West assuming the role of the Flash after the death of Barry Allen (Although Barry was recently resurrected anyway).

The death of characters may also be circumvented by editorial means beyond storyline. Rebooted timelines or recreations of characters in a different fictional universe may introduce dead characters as new, as they belong to the publishing house all the time regardless of their fictional status. Other specific stories may be conceived as not being canon from the start, so that the writers have creative freedom to kill major characters or perform radical changes as they see fit for the narrative, with such changes taking place only in that work and not in the main fictional universe. It can also happen that a writer uses a dead character by mistake, out of ignorance that the character was dead. In this case, the use of that character would become a continuity error until a proper explanation to fix it is given.

See also

References

- ^ IGN Geoff Johns: Inside Blackest Night

- ^ James R. Fleming, Review of Superman on the Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us about Ourselves and Our Society, ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, Winter 2006.

- ^ Captain America, RIP, para. 5, Wall Street Journal, March 13, 2007

- ^ Brian Cronin (March 29, 2007). "Comic Book Urban Legends Revealed # 96". Comic Book Resources. http://goodcomics.comicbookresources.com/2007/03/29/comic-book-urban-legends-revealed-96/.

- ^ Captain America, RIP, para. 5, Wall Street Journal, March 13, 2007

- ^ Captain America, RIP, para. 5, Wall Street Journal, March 13, 2007

- ^ X-Factor #70

- ^ Dallas: Return to Camelot (1) - TV.com

- ^ "Spock dies — but wait! He'll be back!". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press: pp. 1D. 1982-06-03. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=kG8RAAAAIBAJ&sjid=W-IDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2635,627083. Retrieved May 03, 2011.

Examples

- ^ The Green Goblin killed himself by accident shortly after killing Gwen Stacy. He returned during the Clone saga, where it was stated that his powers allowed him to heal

- ^ Mockingbird was killed by Mephisto at the West Coast Avengers title, but the Secret Invasion storyline returned the character, stating that the dead Mockingbird was a skrull posing as her.

- ^ Gwen Stacy returned a pair of years after her death, but it was later revealed that the returned Gwen was actually a clone of the original, created by the Jackal

- ^ Charles Xavier was killed by Legion in the past, which started the Age of Apocalypse storyline. At the end of it Bishop returns to the past and prevents the death of Xavier, which restored continuity.

Superhero fiction Media Plot elements Superhero · Supervillain · Superpower (List) · Secret identity · Alter ego · Comic book death · Women in RefrigeratorsContinuity Categories:- Continuity (fiction)

- Comics terminology

- Narratology

- Superhero fiction

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.